Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington

| The Right Honourable The Earl of Burlington The Earl of Cork KG PC | |

|---|---|

|

Portrait of the 3rd Earl of Burlington by Jonathan Richardson, c. 1718 | |

| Lord High Treasurer of Ireland | |

|

In office 25 August 1715 – 3 December 1753 | |

| Preceded by | The Lord Carleton |

| Succeeded by | Marquess of Hartington |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

25 April 1694 Yorkshire, England |

| Died |

15 December 1753 (aged 59) Chiswick House, London[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Savile, Countess of Burlington and Countess of Cork |

| Children |

Lady Dorothy Boyle, Charlotte Cavendish, Marchioness of Hartington |

Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork, KG PC (25 April 1694 – 15 December 1753) was an Anglo-Irish architect and noble often called the "Apollo of the Arts" and the "Architect Earl". The son of the 2nd Earl of Burlington and 3rd Earl of Cork, Burlington never took more than a passing interest in politics despite his position as a Privy Counsellor and a member of both the British House of Lords and the Irish House of Lords.

Lord Burlington is remembered for bringing Palladian architecture to Britain and Ireland. His major projects include Burlington House, Westminster School, Chiswick House and Northwick Park.

Life

Lord Burlington was born in Yorkshire into a wealthy Anglo-Irish aristocratic family, the son of Charles Boyle, 2nd Earl of Burlington and his wife, Juliana Noel (1672-1750). Often known as "the Architect Earl", Burlington was instrumental in the revival of Palladian architecture in both Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland. He succeeded to his titles and extensive estates in Yorkshire and Ireland at the age of nine, after his father's death in February 1704. During his minority, which lasted until 1715, his English and Irish lands and political interests were managed on his behalf by his mother and guardian, the dowager countess Juliana.[2] He showed an early love of music. Georg Frideric Handel dedicated two operas to him, while staying at Burlington House: Teseo and Amadigi di Gaula. According to Hawkins, Francesco Barsanti dedicated the six recorder sonatas of his Op. 1 to Lord Burlington, although the dedication must have appeared on the manuscript copies sold by Peter Bressan, before Walsh & Hare engraved the works c. 1727.[3] Three foreign Grand Tours 1714 – 1719 and a further trip to Paris in 1726 gave him opportunities to develop his taste. His professional skill as an architect (always supported by a mason-contractor) was extraordinary in an English aristocrat. He carried his copy of Andrea Palladio's book I quattro libri dell'architettura with him in touring the Veneto in 1719, but made notes on only a small number of blank pages, having found the region flooded and many villas inaccessible.[4] In 1719 he was one of main subscribers in the Royal Academy of Music, a corporation that produced baroque opera on stage.[5][6]

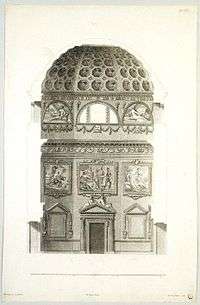

Burlington never closely inspected Roman ruins or made detailed drawings on the sites; he relied on Palladio and Scamozzi as his interpreters of the classic tradition. Another source of his inspiration were drawings he collected, some drawings of Palladio himself, which had belonged to Inigo Jones and many more of Inigo Jones' pupil John Webb, which William Kent published in 1727 (although a date of 1736 is generally accepted) as Some Designs of Mr Inigo Jones... with Some Additional Designs that were by Kent and Burlington. The important role of Jones' pupil Webb in transmitting the palladian—neo-palladian heritage was not understood until the 20th century. Burlington's Palladio drawings include many reconstructions after Vitruvius of Roman buildings, which Burlington planned to publish. In the meantime, in 1723 he adapted the palazzo facade in the illustration for the London house of General Wade in Old Burlington Street, which was engraved for Vitruvius Britannicus iii (1725). The process put a previously unknown Palladio design into circulation.

Burlington's first project, appropriately, was his own London residence, Burlington House, where he dismissed his baroque architect James Gibbs when he returned from the continent in 1719 and employed the Scottish architect Colen Campbell, with the history-painter-turned-designer William Kent for the interiors. The courtyard front of Burlington House, prominently sited in Piccadilly, was the first major executed statement of neo-Palladianism.

In the 1720s Burlington and Campbell parted, and Burlington was assisted in his projects by the young Henry Flitcroft, "Burlington Harry"— who developed into a major architect of the second neopalladian generation— and Daniel Garrett— a straightforward palladian architect of the second rank— and some draughtsmen.

By the early 1730s Palladian style had triumphed as the generally accepted manner for a British country house or public building. For the rest of his life Burlington was "the Apollo of the arts" as Horace Walpole phrased it— and Kent his 'proper priest."

In 1739, Lord Burlington was involved in the founding of a new charitable organisation called the Foundling Hospital. Burlington was a governor of the charity, but did not formally take part in planning the construction of this large Bloomsbury children's home completed in 1742. Architect for the building was a Theodore Jacobsen, who took on the commission as an act of charity.

Many of Burlington's projects have suffered, from rebuilding or additions, from fire, from losses due to urban sprawl. In many cases his ideas were informal: at Holkham Hall the architect Matthew Brettingham recalled that "the general ideas were first struck out by the Earls of Burlington and Leicester, assisted by Mr. William Kent." Brettingham's engraved publication of Holkham credited Burlington specifically with ceilings for the portico and the north dressing-room.

Burlington's architectural drawings, inherited by his son-in-law the Duke of Devonshire, are preserved at Chatsworth, and enable attributions that would not otherwise be possible. In 1751 he sent some of his drawings to Francesco Algarotti in Potsdam together with a book on Vitruvius.[7]

Major projects

- (Burlington House, Piccadilly, London): Burlington's own contribution is likely to have been restricted to the former colonnade (demolished 1868) In London, Burlington offered designs for features at several aristocratic free-standing dwellings, none of which have survived: Queensbury House in Burlington Gardens (a gateway); Warwick House, Warwick Street (interiors); Richmond House, Whitehall (the main building);

- Tottenham Park, Wiltshire, for Charles, Lord Bruce: from 1721, executed by Burlington's protégé Henry Flitcroft (enlarged and remodelled since). In the original house, the high corner pavilion blocks of Inigo Jones' Wilton were provided with the "Palladian window" motif to be seen at Burlington House. Burlington, with a good eye for garden effects, also designed ornamental buildings in the park (demolished)

- Westminster School, the Dormitory: 1722 – 1730 (altered, bombed and restored), the first public work by Burlington, for which Sir Christopher Wren had provided a design, which was rejected in favour of Burlington's, a triumph for the Palladians and a sign of changing English taste.

- Old Burlington Street, London: houses, including one for General Wade: 1723 (demolished). General Wade's house adapted the genuine Palladio facade in Burlington's collection of drawings.

- Waldershare Park, Kent, the Belvedere Tower: 1725 – 27. A design for a garden eye-catcher that might have been attributed to Colen Campbell, were it not for a ground plan among Burlington's drawings at Chatsworth.

- Chiswick House Villa, Middlesex: The "Casina" in the gardens, 1717, was Burlington's first essay. The house he designed for himself was demolished. The villa is one of the gems of European 18th-century architecture.

- Sevenoaks School, School House, 1730. Classic Palladian work, commissioned by his friend Elijah Fenton.

- The York Assembly Rooms: 1731 – 32 (facade remodelled). In the basilica-like space, Burlington attempted an archaeological reconstruction "with doctrinaire exactitude" (Colvin 1995) of the "Egyptian Hall" described by Vitruvius, as it had been interpreted in Palladio's Quattro Libri. The result is one of the grandest Palladian public spaces.

- Castle Hill, Devonshire

- Northwick Park, (now Gloucestershire)

- Kirby Hall, Yorkshire. An elevation

Marriage and children

%2C_Countess_of_Euston%2C_and_Her_Sister_Lady_Charlotte_Boyle_(1731%E2%80%931754)%2C_Later_Marchioness_of_Hartington.jpg)

Burlington married Dorothy Savile on 21 March 1720, the daughter of William Savile, 2nd Marquess of Halifax and his second wife, Mary Finch.

Mary was the daughter of Daniel Finch, 2nd Earl of Nottingham and Lady Essex Rich (d.1684). Essex was the daughter of Robert Rich, 3rd Earl of Warwick and Anne Cheeke. Anne was the daughter of Sir Thomas Cheeke of Pirgo and a senior Essex Rich (d.1659).

The elder Essex was the daughter of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick and Penelope Devereux, Lady Rich. Essex was probably named after her maternal grandfather Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex. Her maternal grandmother was Lettice Knollys.

They had two daughters:

- Lady Dorothy Boyle (14 May 1724 – 2 May 1742). She was married to George Fitzroy, Earl of Euston, second son of Charles FitzRoy, 2nd Duke of Grafton and Lady Henrietta Somerset. No known descendants.

- Lady Charlotte Elizabeth Boyle (27 October 1731 – 8 December 1754). She married William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire. They were parents to William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, George Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington and two other children.

Burlington died at Chiswick House, aged 59. Upon his death, the Earldom of Cork passed to a cousin, John Boyle, and the title of Earl of Burlington became extinct. It was revived in 1831 for his grandson George Cavendish and is now held by the Cavendish family as a courtesy title for the Duke of Devonshire.

Gallery of architectural works

Chiswick House Entrance Front

Chiswick House Entrance Front Chiswick House Garden Front

Chiswick House Garden Front Chiswick House south western view

Chiswick House south western view Westminster School Dormitory

Westminster School Dormitory Burlington House

Burlington House Holkham Hall

Holkham Hall- Tottenham House

References

- ↑ Bolton, Diane K.; Croot, Patricia E. C.; Hicks, M. A. (1982). "Chiswick: Economic history". A History of the County of Middlesex. 7. London: Victoria County History. pp. 78–86. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Wilson, Rachel, Elite Women in Ascendancy Ireland, 1690-1745: Imitation and Innovation (Boydell and Brewer, Woodbridge, 2015). ISBN 978-1783270392

- ↑ Hawkins, Sir John: A General History of the Science and Practice of Music, Vol. 5, p. 372; T. Payne & Sons, London, 1776

- ↑ Burlington to Sir Andrew Fountaine, 6 November 1719; quoted by Clark, J., in Barnard & Clark (eds) 'Lord Burlington, Architecture, Art and Life', 1995, 268.

- ↑ Deutsch, O.E. (1955), Handel. A documentary biography, p. 91. Reprint 1974.

- ↑ See the year 1719 Handel Reference Database (in progress)

- ↑ MacDonogh, G. (1999) Frederick the Great, p. 192, 233–234.

- Additional sources

- Howard Colvin (1995). Dictionary of British Architects. 3rd ed.

- Handel. A Celebration of his Life and Times 1685 – 1759. National Portrait Gallery, London.

External links

- Richard Boyle, Earl of Burlington

- Lord Burlington

- Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Further reading

- Arnold, Dana (Ed.), Belov'd by Ev'ry Muse. Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington & 4th Earl of Cork (1694–1753). Essays to celebrate the tercentenary of the birth of Lord Burlington. London, Georgian Group. 1994. ISBN 0-9517461-3-8

- Harris, John, The Palladians. London, Trefoil. 1981. RIBA Drawings Series. Includes a number of Burlington's designs. ISBN 0-86294-000-1

- Lees-Milne, James, The Earls of Creation. London, Century Hutchinson. 1986. Chapter III: Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington (1694–1753). ISBN 0-7126-9464-1

- Wilton-Ely, John (Intro.), Apollo of the Arts: Lord Burlington and His Circle. Nottingham University Art Gallery. 1973. Exhibition catalogue.

- Wittkower, Rudolf, Palladio and English Palladianism. London, Thames and Hudson. Rep. 1985. ISBN 0-500-27296-4

- Chapter 8: Lord Burlington and William Kent.

- Chapter 9: Lord Burlington's Work at York.

- Chapter 10: Lord Burlington at Northwick Park.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Lord Carleton |

Lord Treasurer of Ireland 1715–1753 |

Succeeded by Marquess of Hartington |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The 5th Viscount of Irvine |

Custos Rotulorum of the East Riding of Yorkshire 1715–1721 |

Succeeded by William Pulteney |

| Preceded by The Lord Carleton |

Custos Rotulorum of the North Riding of Yorkshire 1715–1722 |

Succeeded by Conyers Darcy |

| Vice-Admiral of Yorkshire 1715–1739 |

Succeeded by Sir Conyers Darcy (North Riding) The 7th Viscount of Irvine (East Riding) | |

| Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire 1715–1733 |

Succeeded by The Lord Malton | |

| Preceded by Conyers Darcy |

Custos Rotulorum of the North Riding of Yorkshire 1722–1733 | |

| Preceded by The Duke of Devonshire |

Captain of the Gentlemen Pensioners 1731–1734 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Montagu |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| Preceded by Charles Boyle |

Earl of Cork 1704–1753 |

Succeeded by John Boyle |

| Peerage of England | ||

| Preceded by Charles Boyle |

Earl of Burlington 1704–1753 |

Extinct |

| Baron Clifford 1704–1753 |

Succeeded by Charlotte Cavendish | |