Bowmouth guitarfish

| Bowmouth guitarfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Rajiformes |

| Family: | Rhinidae J. P. Müller and Henle, 1841 |

| Genus: | Rhina Bloch & J. G. Schneider, 1801 |

| Species: | R. ancylostoma |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhina ancylostoma Bloch & J. G. Schneider, 1801 | |

| |

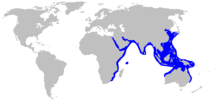

| Range of the bowmouth guitarfish[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Rhina cyclostomus Swainson, 1839 | |

The bowmouth guitarfish (Rhina ancylostoma), also called the shark ray or mud skate, is a species of ray and a member of the family Rhinidae. Its evolutionary affinities are not fully resolved, though it may be related to true guitarfishes and skates. This rare species occurs widely in the tropical coastal waters of the western Indo-Pacific, at depths of up to 90 m (300 ft). Highly distinctive in appearance, the bowmouth guitarfish has a wide and thick body with a rounded snout and large shark-like dorsal and tail fins. Its mouth forms a W-shaped undulating line, and there are multiple thorny ridges over its head and back. It has a dorsal color pattern of many white spots over a bluish gray to brown background, with a pair of prominent black markings over the pectoral fins. This large species can reach a length of 2.7 m (8.9 ft) and weight of 135 kg (298 lb).

Usually found near the sea floor, the bowmouth guitarfish prefers sandy or muddy areas near underwater structures. It is a strong-swimming predator of bony fishes, crustaceans, and molluscs. This species gives live birth to litters of two to eleven pups, which are nourished during gestation by yolk. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the bowmouth guitarfish as Vulnerable because it is widely caught by artisanal and commercial fisheries for its valuable fins and meat. It is viewed as a nuisance by trawlers, however, because its bulk and thorny skin cause it to damage netted catches. Habitat degradation and destruction pose an additional, significant challenge to this ray's survival. The bowmouth guitarfish adapts well to captivity and is displayed in public aquariums.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

German naturalists Marcus Elieser Bloch and Johann Gottlob Schneider described the bowmouth guitarfish in their 1801 Systema Ichthyologiae. Their account was based on a 51 cm (20 in) long specimen, now lost, collected off the Coromandel Coast of India. The genus name Rhina comes from the Greek rhinos ("snout"); the specific epithet ancylostoma is derived from the Greek ankylos ("curved" or "crooked") and stoma ("mouth").[3][4] Although Block and Schneider wrote the epithet as ancylostomus and that form appears in some literature, most modern sources regard the correct form to be ancylostoma.[5] Other common names for this species include shark ray, mud skate, shortnose mud skate, bow-mouthed angel fish, and bow-mouthed angel shark.[6]

The evolutionary relationships between the bowmouth guitarfish and other rays are debated. Morphological evidence generally points to a close relationship between Rhina, Rhynchobatus and Rhynchorhina, which are a group of rays known as the wedgefishes that also have large, shark-like fins. Morphological analyses have tended to place these two genera basally among rays, though some have them as basal to just the guitarfishes (Rhinobatidae) and skates (Rajidae) while others have them basal to all other rays except sawfishes (Pristidae).[7][8][9] A 2012 study based on mitochondrial DNA upheld Rhina and Rhynchobatus as sister taxa related to the guitarfishes, but also unexpectedly found that they formed a clade with the sawfishes rather than the skates.[10] Following the description of Rhynchorhina in 2016, a study of mtDNA found that it is part of the same group and their phylogenetic relationship is ((Rhynchobatus+Rhynchorhina)+Rhina).[11]

In terms of classification, Bloch and Schneider originally placed the bowmouth guitarfish in the order Abdominales, a now-obsolete grouping of fishes defined by the positioning of their pelvic fins directly behind the pectoral fins.[3] Modern sources have included it variously in the order Rajiformes, Rhinobatiformes, Rhiniformes, or the newly proposed Rhinopristiformes.[8][10] The placement of the bowmouth guitarfish in the family Rhinidae originates from the group "Rhinae", consisting of Rhina and Rhynchobatus, in Johannes Müller and Jakob Henle's 1841 Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen.[12] Later authors have also assigned this species to the family Rhinobatidae or Rhynchobatidae.[8][13] Joseph Nelson, in the 2006 fourth edition of Fishes of the World, placed this species as the sole member of Rhinidae in the order Rajiformes, which is supported by morphological but not molecular data.[9][14] More recent authorities have placed it in Rhinidae together with Rhynchobatus and Rhynchorhina, reflecting both genetic data and the morphologically intermediate position of Rhynchobatus between Rhina and Rhynchorhina.[11][15]

Description

The bowmouth guitarfish is a heavily built fish growing to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) long and 135 kg (298 lb) in weight.[2][6] The head is short, wide, and flattened with an evenly rounded snout; the front portion of the head, including the medium-sized eyes and large spiracles, is clearly distinct from the body. The long nostrils are transversely oriented and have well-developed skin flaps on their anterior margins. The lower jaw has three protruding lobes that fit into corresponding depressions in the upper jaw.[2][16] There are around 47 upper and 50 lower tooth rows arranged in winding bands; the teeth are low and blunt with ridges on the crown. The five pairs of ventral gill slits are positioned close to the lateral margins of the head.[2][17]

The body is deepest in front of the two tall and falcate (sickle-shaped) dorsal fins. The first dorsal fin is about a third larger than the second and originates over the pelvic fin origins. The second dorsal fin is located midway between the first dorsal and the caudal fin. The broad and triangular pectoral fins have a deep indentation where their leading margins meet the head. The pelvic fins are much smaller than the pectoral fins, and the anal fin is absent. The tail is much longer than the body and ends in a large, crescent-shaped caudal fin; the lower caudal fin lobe is more than half the length of the upper.[2][13][16]

The entire dorsal surface of the bowmouth guitarfish has a grainy texture from a dense covering of tiny dermal denticles. A thick ridge is present along the midline of the back, which bears a band of sharp, robust thorns. There are also a pair of thorn-bearing ridges in front of the eyes, a second pair running from above the eyes to behind the spiracles, and a third pair on the "shoulders". This species is bluish to brownish gray above, lightening towards the margins of the head and over the pectoral fins. There are prominent white spots scattered over the body and fins, a white-edged black marking above each pectoral fin, and two dark transverse bands atop the head between the eyes. The underside is light gray to white. Young rays are more vividly colored than adults, which are browner with fainter patterning and proportionately smaller spots.[2]

Distribution and habitat

While uncommon, the bowmouth guitarfish is widely distributed in the coastal tropical waters of the western Indo-Pacific. In the Indian Ocean, it is found from KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa to the Red Sea (including the Seychelles), across the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia (including the Maldives), to Shark Bay in Western Australia. Its Pacific range extends northward to Korea and southern Japan, eastward to New Guinea, and southward to New South Wales.[2][16] Found between 3 and 90 m (10 and 300 ft) deep, this ray spends most of its time near the sea floor but can occasionally be seen swimming in midwater. It favors sandy or muddy habitats, and can also be found in the vicinity of rocky and coral reefs and shipwrecks.[2][18]

Biology and ecology

The bowmouth guitarfish is a strong swimmer that propels itself with its tail like a shark. It is more active at night and is not known to be territorial.[19] This species feeds mainly on demersal bony fishes such as croakers and crustaceans such as crabs and shrimp; bivalves and cephalopods are also consumed. Its bands of flattened teeth allow it to crush hard-shelled prey.[13][20] Curiously, two bowmouth guitarfishes examined in a 2011 stable isotope study were found to have fed on pelagic rather than demersal animals, in contrast to previous observations.[21]

The tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) is known to prey on the bowmouth guitarfish.[22] The ray is protected by the thorns on its head and back, and it may ram perceived threats.[6] Parasites documented from this species include the tapeworms Carpobothrium rhinei,[23] Dollfusiella michiae,[24] Nybelinia southwelli,[25] Stoibocephalum arafurense,[26] and Tylocephalum carnpanulatum,[27] the leech Pontobdella macrothela,[28] the trematode Melogonimus rhodanometra,[29] the monogeneans Branchotenthes robinoverstreeti[30] and Monocotyle ancylostomae,[31] and the copepods Nesippus vespa,[32] Pandarus cranchii, and P. smithii.[33] There is a record of a bowmouth guitarfish being cleaned by bluestreak cleaner wrasses (Labroides dimidiatus).[18]

Reproduction in the bowmouth guitarfish is viviparous, with the developing embryos sustained to term by yolk. Adult females have a single functional ovary and uterus. The litter size varies between two and eleven pups, and newborns measure 45–51 cm (18–20 in) long.[18][34][35] Sexual maturity is attained at lengths of 1.5–1.8 m (4.9–5.9 ft) for males and over 1.8 m (5.9 ft) in females. Females grow larger than males.[2][20]

Human interactions

Throughout its range, the bowmouth guitarfish is caught incidentally or intentionally by artisanal and commercial fisheries using trawls, gillnets, and line gear.[1] The fins are extremely valuable due to their use in shark fin soup, and are often the only parts of the fish kept and brought to market. However, the meat may also be sold fresh or dried and salted, and it is highly esteemed in India.[6][20] When caught as bycatch in trawls, the bowmouth guitarfish is considered a nuisance because its strength and rough skin make it difficult to handle, and as the heavy ray thrashes in the net it can damage the rest of the catch.[2] In Thailand, the enlarged thorns of this species are used to make bracelets.[36]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the bowmouth guitarfish as Vulnerable. It is threatened by fishing and by habitat destruction and degradation, particularly from blast fishing, coral bleaching, and siltation. Its numbers are known to have declined substantially in Indonesian waters, where it is one of the large rays targeted by a mostly unregulated gillnet fishery. The IUCN has given this species a regional assessment of Near Threatened in Australian waters, where it is not a targeted species but is taken as bycatch in bottom trawls. The installation of turtle excluder devices on some Australian trawlers has benefited this species.[1] Since it is rare and faces many conservation threats, the bowmouth guitarfish has been called "the panda of the aquatic world".[37]

It is a popular subject of public aquariums and fares relatively well, with one individual having lived for seven years in captivity.[2][18] In 2007, the Newport Aquarium in Kentucky initiated the world's first captive breeding program for this species.[37] Newport Aquarium announced in January 2014 that the female, "Sweet Pea", had become pregnant and given birth to seven pups.[38] By February 2014, all seven pups had died.[39] On January 7, 2016, Sweet Pea gave birth to nine shark pups[40] which were eating on their own and still gaining weight by February 10, 2016.[41] Newport Aquarium later announced that the pups would be moved into a coral reef exhibit where they can be viewed by the public starting on June 24.[42] The species also bred at the S.E.A. Aquarium in Singapore in 2015.[43]

References

- 1 2 3 McAuley, R. & L.J.V. Compagno (2003). "Rhina ancylostoma". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Last, P.R.; Stevens, J.D. (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 299–300. ISBN 0-674-03411-2.

- 1 2 Bloch, M.E.; Schneider, J.G. (1801). Systema Ichthyologiae Iconibus CX Ilustratum. Berolini. p. 352.

- ↑ Paepke, H.J. (2000). Bloch's Fish Collection in the Museum für Naturkunde der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin: An Illustrated Catalog and Historical Account. Koeltz Scientific Books. pp. 122–123. ISBN 3-904144-16-2.

- ↑ Eschmeyer, W.N. (ed.). "ancylostomus, Rhina". Catalog of Fishes. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Froese, R.; Pauly, D., eds. (2011). "Rhina ancylostoma, Bowmouth guitarfish". FishBase. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ↑ Nishida, K. (1990). "Phylogeny of the suborder Myliobatoidei". Memoirs of the Faculty of Fisheries, Hokkaido University. 37: 1–108.

- 1 2 3 McEachran, J.D.; N. Aschliman (2004). "Phylogeny of Batoidea". In Carrier, L.C.; J.A. Musick; M.R. Heithaus. Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives. CRC Press. pp. 79–113. ISBN 0-8493-1514-X.

- 1 2 Aschliman, N.C.; Claeson, K.M.; McEachran, J.D. (2012). "Phylogeny of Batoidea". In Carrier, J.C.; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R. Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (second ed.). CRC Press. pp. 57–98. ISBN 1439839247.

- 1 2 Naylor, G.J.; Caira, J.N.; Jensen, K.; Rosana, K.A.; Straube, N.; Lakner, C. (2012). Carrier, J.C.; Musick, J.A.; Heithaus, M.R., eds. "The Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives" (second ed.). CRC Press: 31–57. ISBN 1-4398-3924-7.

|chapter=ignored (help) - 1 2 Séret, B.; and G. Naylor (2016). "Rhynchorhina mauritaniensis, a new genus and species of wedgefish from the eastern central Atlantic (Elasmobranchii: Batoidea: Rhinidae)". Zootaxa. 4138 (2): 291–308. PMID 27470765. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4138.2.4.

- ↑ Müller, J.; Henle, F.G.J. (1841). Systematische Beschreibung der Plagiostomen (volume 2). Veit und Comp. p. 110.

- 1 2 3 Compagno, L.J.V.; Last, P.R. (1999). "Rhinidae". In Carpenter, K.E.; Niem, V.H. FAO Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes: The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 1418–1422. ISBN 92-5-104302-7.

- ↑ Nelson, J.S. (2006). Fishes of the World (fourth ed.). John Wiley. pp. 71–74. ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- ↑ Last; White; de Carvalho; Séret; Stehmann; and Naylor, eds. (2016). Rays of the World. CSIRO. p. 76. ISBN 9780643109148.

- 1 2 3 Randall, J.E.; Hoover, J.P. (1995). Coastal Fishes of Oman. University of Hawaii Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-8248-1808-3.

- ↑ Smith, J.L.B.; Smith, M.M.; Heemstra, P.C. (2003). Smith's Sea Fishes. Struik. pp. 128–129. ISBN 1-86872-890-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Michael, S.W. (1993). Reef Sharks & Rays of the World. Sea Challengers. p. 71. ISBN 0-930118-18-9.

- ↑ Ferrari, A.; Ferrari, A. (2002). Sharks. Firefly Books. p. 203. ISBN 1-55209-629-7.

- 1 2 3 Raje, S.G. (2006). "Skate fishery and some biological aspects of five species of skates off Mumbai". Indian Journal of Fisheries. 53 (4): 431–439.

- ↑ Borrell, A.; Cardona, L.; Kumarran, R.P.; Aguilar, A. (2011). "Trophic ecology of elasmobranchs caught off Gujarat, India, as inferred from stable isotopes". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 68 (3): 547–554. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsq170.

- ↑ Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Goodreid, A.B.; McAuley, R.B. (2001). "Size, sex and geographic variation in the diet of the tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier, from Western Australian waters". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 61: 37–46. doi:10.1023/A:1011021710183.

- ↑ Sarada, S.; Lakshmi, C.V.; Rao, K.H. (1995). "Studies on a new species Carpobothrium rhinei (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea) from Rhina ancylostomus from Waltair coast". Uttar Pradesh Journal of Zoology. 15 (2): 127–129.

- ↑ Campbell, R.A.; Beveridge, I. (2009). "Oncomegas aetobatidis sp nov (Cestoda: Trypanorhyncha), a re-description of O. australiensis Toth, Campbell & Schmidt, 1992 and new records of trypanorhynch cestodes from Australian elasmobranch fishes". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 133: 18–29.

- ↑ Palm, H.W.; Walter, T. (1999). "Nybelinia southwelli sp. nov. (Cestoda, Trypanorhyncha) with the re-description of N. perideraeus (Shipley & Hornell, 1906) and synonymy of N. herdmani (Shipley & Hornell, 1906) with Kotorella pronosoma (Stossich, 1901)". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum Zoology Series. 65 (2): 123–131.

- ↑ Cielocha, J.J.; Jensen, K. (2013). "Stoibocephalum n. gen. (Cestoda: Lecanicephalidea) from the sharkray, Rhina ancylostoma Bloch & Schneider (Elasmobranchii: Rhinopristiformes), from northern Australia". Zootaxa. 3626 (4): 558–568. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3626.4.9.

- ↑ Butler, S.A. (1987). "Taxonomy of Some Tetraphyllidean Cestodes From Elasmobranch Fishes". Australian Journal of Zoology. 35 (4): 343–371. doi:10.1071/ZO9870343.

- ↑ de Silva, P.H.D.H. (1963). "The occurrence of Pontobdella (Pontobdellina) macrothela Schmarda and Pontobdella aculeata Harding in the Wadge Bank". Spolia Zeylanica. 30 (1): 35–39.

- ↑ Bray, R.A.; Brockerhoff, A.; Cribb, T.H. (January 1995). "Melogonimus rhodanometra n. g., n. sp. (Digenea: Ptychogonimidae) from the elasmobranch Rhina ancylostoma Bloch & Schneider (Rhinobatidae) from the southeastern coastal waters of Queensland, Australia". Systematic Parasitology. 30 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1007/BF00009239.

- ↑ Bullard, S.A.; Dippenaar, S.M. (June 2003). "Branchotenthes robinoverstreeti n. gen. and n. sp. (Monogenea: Hexabothriidae) from Gill Filaments of the Bowmouth Guitarfish, Rhina ancylostoma (Rhynchobatidae), in the Indian Ocean". The Journal of Parasitology. 89 (3): 595–601. PMID 12880262. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0595:BRNGAN]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Zhang, J.Y.; Yang, T.B.; Liu, L.; Ding, X.J. (2003). "A list of monogeneans from Chinese marine fishes". Systematic Parasitology. 54 (2): 111–130. PMID 12652065. doi:10.1023/A:1022581523683.

- ↑ Dippenaar, S.M.; Mathibela, R.B.; Bloomer, P. (2010). "Cytochrome oxidase I sequences reveal possible cryptic diversity in the cosmopolitan symbiotic copepod Nesippus orientalis Heller, 1868 (Pandaridae: Siphonostomatoida) on elasmobranch hosts from the KwaZulu-Natal coast of South Africa". Experimental Parasitology. 125 (1): 42–50. PMID 19723521. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2009.08.017.

- ↑ Izawa, K. (2010). "Redescription of eight species of parasitic copepods (Siphonostomatoida, Pandaridae) infecting Japanese elasmobranchs". Crustaceana. 83 (3): 313–341. doi:10.1163/001121609X12591347509329.

- ↑ Devadoss, P.; Batcha, H. (1995). "Some observations on the rare bow-mouth guitar fish Rhina ancylostoma". Indian Council of Agricultural Research Marine Fisheries Information Service Technical and Extension Series. 138: 10–11.

- ↑ Last, P.R.; White, W.T.; Caire, J.N.; Dharmadi; Fahmi; Jensen, K.; Lim, A.P.F.; Manjaji-Matsumoto, B.M.; Naylor, G.J.P.; Pogonoski, J.J.; Stevens, J.D.; Yearsley, G.K. (2010). Sharks and Rays of Borneo. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-1-921605-59-8.

- ↑ Fowler, S.L.; Reed, T.M.; Dipper, F.A., eds. (2002). Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997. IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group. p. 112. ISBN 2-8317-0650-5.

- 1 2 "Newport Aquarium Launches World’s First Shark Ray Breeding Program, Adds Rare Male Shark Ray". UnderwaterTimes. February 1, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Newport Aquarium’s Sweet Pea, the First Documented Shark Ray to Breed in Captivity, Gives Birth to Seven Pups". Aquarium Works. Newport Aquarium. January 29, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Newport Aquarium says shark ray pups died". WKRC-TV. 26 February 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ↑ "Newport Aquarium shark ray gives birth to nine pups". FOX19NOW. 7 January 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ "Shark Ray Pups Reach Milestones". aquariumworks.org. 10 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ Ferrell, Nikki. "Rare shark ray pups to move to exhibit at Newport Aquarium". Retrieved 2016-06-25.

- ↑ "S.E.A. Aquarium successfully breeds shark ray pup, a vulnerable species". The Straits Times. 5 May 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.