B. Traven

| B. Traven | |

|---|---|

Ret Marut arrest photo taken in London (1923); Marut is the most popular candidate for Traven's true identity. | |

| Born |

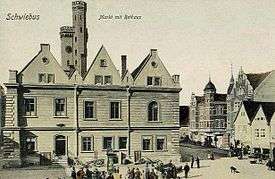

February 23, 1882? February 25, 1882? May 3, 1890? Schwiebus, Brandenburg, German Empire? |

| Died |

March 26, 1969 (aged 87)? Mexico City, Mexico |

| Occupation | writer |

| Nationality | German |

| Citizenship |

Mexico (from 1951?) before this U.S? |

| Notable works |

The Death Ship The Treasure of the Sierra Madre The Jungle Novels |

| Spouse | Rosa Elena Luján (1957–1969)? |

B. Traven (Bruno Traven in some accounts) was the pen name of a presumably German novelist, whose real name, nationality, date and place of birth and details of biography are all subject to dispute. One of the few certainties about Traven's life is that he lived for years in Mexico, where the majority of his fiction is also set—including The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1927), which was adapted for the Academy Award winning film of the same name in 1948.

Virtually every detail of Traven's life has been disputed and hotly debated. There were many hypotheses on the true identity of B. Traven, some of them wildly fantastic. Most agree that Traven was Ret Marut, a German stage actor and anarchist, who supposedly left Europe for Mexico around 1924.[1] Researchers further argue that Marut/Traven's real name was Otto Feige and that he was born in Schwiebus in Brandenburg, modern day Świebodzin in Poland. B. Traven in Mexico is also connected with the names of Berick Traven Torsvan and Hal Croves, both of whom appeared and acted in different periods of the writer's life. Both, however, denied being Traven and claimed that they were his literary agents only, representing him in contacts with his publishers.

B. Traven is the author of twelve novels, one book of reportage and several short stories, in which the sensational and adventure subjects combine with a critical attitude towards capitalism. B. Traven's best known works include the novels The Death Ship from 1926, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre from 1927 (filmed in 1948 by John Huston), and the so-called "Jungle Novels," also known as the Caoba cyclus (from the Spanish word caoba, meaning mahogany). The Jungle Novels are a group of six novels (including The Carreta and Government), published in the years 1930–1939 and set among Mexican Indians just before and during the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century. B. Traven's novels and short stories became very popular as early as the interwar period and retained this popularity after the Second World War; they were also translated into many languages. Most of B. Traven's books were published in German first and their English editions appeared later; nevertheless the author always claimed that the English versions were the original ones and that the German versions were only their translations. This claim is not taken seriously.

Works

Novels

The writer with the pen name B. Traven appeared on the German literary scene in 1925, when the Berlin daily Vorwärts, the organ of the Social Democratic Party of Germany, published the first short story signed with this pseudonym on 28 February. Soon, it published Traven's first novel, Die Baumwollpflücker (The Cotton Pickers), which appeared in installments in June and July of the same year. The expanded book edition was published in 1926 by the Berlin-based Buchmeister publishing house, which was owned by the left-leaning, trade unions affiliated book sales club Büchergilde Gutenberg. The title of the first book edition was Der Wobbly, a common name for members of the anarcho-syndicalist trade union Industrial Workers of the World; in later editions the original title Die Baumwollpflücker was restored. In the book, Traven introduced for the first time the figure of Gerald Gales (in Traven's other works his name is Gale, or Gerard Gales), an American sailor who looks for a job in different occupations in Mexico, often consorting with suspicious characters and witnessing capitalistic exploitation, nevertheless not losing his will to fight and striving to draw joy from life.[2]

In the same year (1926), the book club Büchergilde Gutenberg, which was Traven's publishing house until 1939, published his second novel Das Totenschiff (The Death Ship). The main character of the novel is again Gerald Gale, a sailor who, having lost his documents, virtually forfeits his identity, the right to normal life and home country and, consequently, is forced to work as a stoker's helper in extremely difficult conditions on board a "death ship" (meaning a coffin ship), which sails on suspicious voyages around the European and African coasts. The novel is an accusation of the greed of capitalist employers and bureaucracy of officials who deport Gale from the countries where he is seeking refuge. In the light of findings of Traven's biographers, The Death Ship may be regarded as a novel with autobiographical elements. Assuming that B. Traven is identical with the revolutionary Ret Marut, there is a clear parallel between the fate of Gale and the life of the writer himself, devoid of his home country, who might have been forced to work in a boiler room of a steamer on a voyage from Europe to Mexico.[2][3]

Traven's best known novel, apart from The Death Ship, was The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, published first in German in 1927 as Der Schatz der Sierra Madre. The action of the book is again set in Mexico, and its main characters are a group of American adventurers and gold seekers. In 1948 the book was filmed under the same title (The Treasure of the Sierra Madre) by the Hollywood director John Huston. The film, starring Humphrey Bogart and Walter Huston, was a great commercial success, and in 1949 it won three Academy Awards.[2]

The figure of Gerald Gales returned in Traven's next book, The Bridge in the Jungle (Die Brücke im Dschungel), which was serialized in Vorwärts in 1927 and published in an extended book form in 1929. In the novel, Traven first dealt in detail with the question of the Indians living in America and with the differences between Christian and Indian cultures in Latin America; these problems dominated his later Jungle Novels.[2][3]

In 1929 B. Traven's most extensive book The White Rose (Die Weiße Rose) was published; this was an epic story (supposedly based on fact) of land stolen from its Indian owners for the benefit of an American oil company.

The 1930s are mainly the period in which Traven wrote and published the so-called Jungle Novels – the series of six novels consisting of The Carreta (Der Karren, 1931), Government (Regierung, 1931), March to the Monteria (Der Marsch ins Reich der Caoba, 1933), Trozas (Die Troza, 1936), The Rebellion of the Hanged (Die Rebellion der Gehenkten, 1936), and The General from the Jungle (Ein General kommt aus dem Dschungel, with a Swedish translation published in 1939 and the German original in 1940). The novels describe the life of Mexican Indians in the state of Chiapas in the early 20th century who are forced to work under inhuman conditions at clearing mahogany in labour camps (monterias) in the jungle; this results in rebellion and the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution.[2][3]

After the Jungle Novels, B. Traven practically stopped writing longer literary forms, publishing only short stories, including the novella or Mexican fairy tale Macario, which was originally written in English but first published in German in 1950. The story, whose original English title was The Healer, was honored by The New York Times as the best short story of the year in 1953. Macario was made into a film by Mexican director Roberto Gavaldón in 1960.

Traven's last novel, published in 1960, was Aslan Norval (so far not translated into English), the story of an American millionairess who is married to an aging businessman and at the same time in love with a young man; she intends to build a canal running across the United States as an alternative for the nuclear arms race and space exploration programs. The subject and the language of the novel, which were completely different from the writer's other works, resulted in its rejection for a long time by publishers who doubted Traven's authorship; the novel was accused of being "trivial" and "pornographic". The book was only accepted after its thorough stylistic editing by Johannes Schönherr who adapted its language to the "Traven style". Doubts about Aslan Norval remain and exacerbate the problems of the writer's identity and the true authorship of his books.[2][4]

Other works

Apart from his twelve novels, B. Traven also authored many short stories, some of which remain unpublished. Besides the already mentioned Macario, the writer adapted the Mexican legend about The Creation of the Sun and the Moon (Sonnen-Schöpfung, with a Czech translation published in 1934 and the German original in 1936). The first collection of Traven's short stories, entitled Der Busch, appeared in 1928; its second, enlarged edition was published in 1930. From the 1940s onwards many of his short stories also appeared in magazines and anthologies in different languages.[2]

A solitary position in Traven's oeuvre is held by Land des Frühlings (Land of Springtime, 1928), a travel book about the Mexican state of Chiapas that doubles as a soapbox for the presentation of the leftist and anarchist views of its author. The book, published by Büchergilde Gutenberg like his other works, contained 64 pages of photographs taken by B. Traven himself. It has not been translated into English.

Themes in B. Traven's works

B. Traven's writings can be best described as "proletarian adventure novels". They tell about exotic travels, outlaw adventurers and Indians; many of their motifs can also be found in Karl May's and Jack London's novels. Unlike much of adventure or Western fiction, Traven's books, however, are not only characterized by a detailed description of the social environment of their protagonists but also by the consistent presentation of the world from the perspective of the "oppressed and exploited". Traven's characters are drawn commonly from the lower classes of society, from the proletariat or lumpenproletariat strata; they are more antiheroes than heroes, and despite that they have this primal vital force which compels them to fight. The notions of "justice" or Christian morality, which are so visible in adventure novels by other authors, for example Karl May, are of no importance here.

Instead, an anarchist element of rebellion often lies at the centre of the novel's action. The hero's rejection of his degrading living conditions frequently serves as motive and broad emphasis is placed upon the efforts of the oppressed to liberate themselves. Apart from that, there are virtually no political programmes in Traven's books; his clearest manifesto may be the general anarchist demand "Tierra y Libertad" in the Jungle Novels. Professional politicians, including ones who sympathize with the left, are usually shown in a negative light, if shown at all. Despite this, Traven's books are par excellence political works. Although the author does not offer any positive programme, he always indicates the cause of suffering of his heroes. This source of suffering, deprivation, poverty and death is for him capitalism, personified in the deliberations of the hero of The Death Ship as Caesar Augustus Capitalismus.[5] Traven's criticism of capitalism is, however, free of blatant moralizing. Dressing his novels in the costume of adventure or western literature, the writer seeks to appeal to the less educated, and first of all to the working class.

In his presentation of oppression and exploitation, Traven did not limit himself to the criticism of capitalism; in the centre of his interest there were rather racial persecutions of Mexican Indians. These motifs, which are mainly visible in the Jungle Novels, were a complete novelty in the 1930s. Most leftist intellectuals, despite their negative attitude to European and American imperialism, did not know about, or were not interested in persecutions of natives in Africa, Asia or South America. Traven deserves credit for drawing public attention to these questions, long before anti-colonial movements and struggle for emancipation of black people in the United States.[3]

The mystery of B. Traven's biography

B. Traven submitted his works himself or through his representatives for publication from Mexico to Europe by post and gave a Mexican post office box as his return address. The copyright holder named in his books was "B. Traven, Tamaulipas, Mexico". Neither the European nor the American publishers of the writer ever met him personally or, at least, the people with whom they negotiated the publication and later also the filming of his books always maintained they were only Traven's literary agents; the identity of the writer himself was to be kept secret. This reluctance to offer any biographical information was explained by B. Traven in words which were to become one of his best-known quotations:

The creative person should have no other biography than his works.[2][6]

The non-vanity and non-ambition claimed by Traven was no humble gesture, Jan-Christoph Hauschild writes:

By deleting his former names Feige and Marut, he extinguished his hitherto existences and created a new one, including a suitable story of personal descent. Traven knew that values like credibility and authenticity were effective criteria in the literary matters he dealt with and that he needed to consider them. Above all, his performance was self-fulfilment, and after that the creation of an artist. Even as Ret Marut he played parts on stage but also in the stalls and in real life, so he equipped and coloured them with adequate and fascinating stories of personal descent till they became a spleeny mixture of self-discovery, self-invention, performance and masquerade. It seems indisputable that Traven’s hide-and-seek manners became progressively obsessive; although we have to consider that self-presentation is irrevocable. This turned into a trap because he was no longer able to expose his true vita without appearing as a show-off.[7]

Although the popularity of the writer was still rising (the German Brockhaus Enzyklopädie devoted an article to him as early as 1934,[8]) B. Traven remained a mysterious figure. Literary critics, journalists and others were trying to discover the author's identity and were proposing more or less credible, sometimes fantastic hypotheses.

Ret Marut theory

The author of the first hypothesis concerning B. Traven's identity was the German journalist, writer and anarchist Erich Mühsam, who conjectured that the person who hides behind the pseudonym was the former actor and journalist Ret Marut. Marut, whose date and place of birth are unknown, performed on stage in Idar (today Idar-Oberstein), Ansbach, Suhl, Crimmitschau, Berlin, Danzig and Düsseldorf before the First World War. From time to time, he also directed plays and wrote articles on theatre subjects. After the outbreak of the war, in 1915, he declared to the German authorities that he was an American citizen. Marut also became politically engaged when, in 1917, he launched the periodical Der Ziegelbrenner (The Brick Burner) with a clearly anarchistic profile (its last issue appeared in 1921). After the proclamation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic in Munich in 1919, Ret Marut was made director of the press division and member of the propaganda committee of this anarchist Schein-Räterepublik (Fake-Soviet Republic), as the communists under Eugen Leviné, who took over after a week, called it. Marut got to know Erich Mühsam, one of the leaders of the anarchists in Munich. Later, when B. Traven's first novels appeared, Mühsam compared their style and content with Marut's Der Ziegelbrenner articles and came to the conclusion that they must have been written by one and the same person. Ret Marut was arrested after the overthrow of the Bavarian Soviet Republic on May 1, 1919 and taken to be executed, but managed to escape (it is said). All this may explain why Traven always claimed to be American and denied any connections with Germany; a warrant, in the German Reich, had been out for Ret Marut's arrest since 1919.[8][9]

Rolf Recknagel, an East German literary scholar from Leipzig, came to very similar conclusions as Erich Mühsam. In 1966, he published a biography of Traven[10] in which he claimed that the books signed with the pen name B. Traven (including the post-war ones) had been written by Ret Marut. At present, this hypothesis is accepted by most "Travenologists".[11]

Otto Feige theory

The Ret Marut hypothesis did not explain how the former actor and anarchist reached Mexico; it did not provide any information about his early life either. In the late 1970s, two BBC journalists, Will Wyatt and Robert Robinson, decided to investigate this matter. The results of their research were published in a documentary broadcast by the BBC on 19 December 1978 and in Wyatt's book The Man who Was B. Traven (U.S. title The Secret of the Sierra Madre)[12] which appeared in 1980. The journalists gained access to Ret Marut's files in the United States Department of State and the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office; from these they discovered that Marut attempted to travel from Europe, via Britain, to Canada in 1923, but was turned back from that country. He was finally arrested and imprisoned as a foreigner without a residence permit in Brixton Prison, London on 30 November 1923.

Interrogated by the British police, Marut testified that his real name was Hermann Otto Albert Maximilian Feige and that he had been born in Schwiebus in Germany (modern day Świebodzin in Poland) on 23 February 1882. Wyatt and Robinson did research in the Polish archives and confirmed the authenticity of these facts; both the date and place of birth and the Christian names of Feige's parents agreed with Marut's testimony. The British journalists discovered further that after his apprenticeship and National Service in the German army around 1904/1905 Otto Feige disappeared leaving no trace except for a photograph made by a studio in Magdeburg. Robinson showed photographs of Marut and Traven to a brother and a sister of Feige, and they appeared to recognise the person in the photos as their brother. In 2008 Jan-Christoph Hauschild did research in German archives and confirmed the authenticity of the family memories. After working as a mechanic in Magdeburg, Feige became (summer 1906) head of the metal workers' union in Gelsenkirchen. In September 1907 he left the city and turned into Ret Marut, actor, born in San Francisco. He started his career in Idar (today Idar-Oberstein).[7]

Ret Marut was held in Brixton prison until 15 February 1924. After his release in the spring of 1924, he went to the US consulate in London and asked for confirmation of his American citizenship. He claimed that he had been born in San Francisco in 1882, signed on a ship when he was ten and had been travelling around the world since then, but now wanted to settle down and get his life in order. Incidentally, Marut had also applied for US citizenship earlier when he lived in Germany. He filed altogether three applications at that time, claiming that he had been born in San Francisco on 25 February 1882 to parents William Marut and Helena Marut née Ottarent.[4] The consulate officials did not take this story seriously, especially as they also received the other version of Marut's biography from the London police, about his birth in Schwiebus, which he had presented during the interrogation. Birth records in San Francisco were destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire, and for several decades afterward false claims of birth there were common.[13] In the opinion of Wyatt and Robinson, the version presented by Marut to the police was true – B. Traven was born as Otto Feige in Schwiebus (modern day Świebodzin) and only later changed his name to Ret Marut, his stage name Marut being the anagram of traum (dream in German).[8] Further gilding the lily, the name is an anagram of turma (herd in Romanian, accident in Finnish, and squadron or swarm in Latin).

The above dates of Marut's supposed incarceration in the UK are called into question by existing travel documents. On 27 July 1923, a 41-year-old US citizen named Ret Marut left Liverpool aboard the SS Magentic bound for Quebec and Montreal, Canada.[14] The passenger list from Liverpool states that Marut's original point of departure was Copenhagen, Denmark, and lists question marks under his country of residence and country of citizenship.[15] Upon disembarking in Canada, he declared his intent to travel to the USA via Canada, that he was born in the US, a US citizen, had 50 dollars in his possession, and listed his occupation as a farmer and his language as "American."[16]

The hypothesis that B. Traven is identical with Ret Marut and Otto Feige is nowadays accepted by many scholars. Tapio Helen points out that the adoption of such a version of the writer's biography would be very difficult to reconcile with the many Americanisms in his works and the general spirit of American culture pervading them; these must be proof of at least a long life of the writer in the American environment which was not the case in Feige's or Marut's biography. On the other hand, if Marut was not identical with Otto Feige, it is difficult to explain how he knew the details of his birth so well, including his mother's maiden name, and the similarity of the faces and the handwriting.[8]

The Otto Feige hypothesis had been rejected by Karl S. Guthke who believed that Marut's version about his birth in San Francisco was nearer the truth even though Guthke agreed with the opinion that Marut fantasized in his autobiography to some extent.[17]

Arrival in Mexico

After his release from the London prison, Ret Marut supposedly traveled from Europe to Mexico. The circumstances of this journey are not clear either. According to Rosa Elena Luján, the widow of Hal Croves, who is identified with B. Traven by many scholars (see below), her husband signed on a "death ship" after his release from prison and sailed to Norway, from there on board another "death ship" to Africa and, finally, on board a Dutch ship, reached Tampico on the Gulf of Mexico in the summer of 1924. He allegedly utilized his experiences from these voyages later in the novel The Death Ship.[18] These assertions are partly supported by documents. Marut's name is on the list of the crew members of the Norwegian ship Hegre, which sailed from London to the Canary Islands on 19 April 1924; the name is, however, crossed out, which could imply that Marut did not take part in the voyage in the end.[8]

In the spring of 1917, after the United States entered the First World War, Mexico became a haven for Americans fleeing universal military conscription. In 1918, Linn A(ble) E(aton) Gale (1892–1940) and his wife Magdalena E. Gale fled from New York to Mexico City. Gale soon was a founding member of one of the early Communist Parties of Mexico (PCM). The Gales published the first Mexican issue of their periodical Gale's Journal (August 1917 – March 1921), sometimes subtitled The Journal of Revolutionary Communism in October 1918. In 1918, the Mexican section of the anarcho-syndicalist trade union Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was also established; members of the IWW were known as "Wobblies". This was certainly a favourable environment for an anarchist and fugitive from Europe. In December 1920 Gale had even published an article in his magazine inviting revolutionaries to come. Gale, the person and the name, could have been the source for the figure of Gerald Gale, the hero of many novels by B. Traven, including The Cotton Pickers (first published as Der Wobbly) and The Death Ship. But from Traven's preserved notes, it does not appear that he also had to work in difficult conditions as a day labourer on cotton plantations and in oil fields.[4][19]

However, as, Tapio Helen points out, there is an enormous contrast between the experiences and life of Marut, an actor and bohemian in Munich, and Traven's novels and short stories, characterized by their solid knowledge of Mexican and Indian cultures, seafaring themes, the problems of itinerant workers, political agitators and social activists of all descriptions, and pervaded with Americanisms.[8]

A solution to this riddle was proposed by the Swiss researcher Max Schmid, who put forward the so-called Erlebnisträger ("experience carrier") hypothesis in a series of eight articles published in the Zurich daily Tages-Anzeiger at the end of 1963 and the beginning of 1964.[20] According to this hypothesis (which was published by Schmid under the pseudonym Gerard Gale!), Marut arrived in Mexico from Europe around 1922/1923 and met an American tramp, someone similar to Gerard Gale, who wrote stories about his experiences. Marut obtained these manuscripts from him (probably by trickery), translated them into German, added some elements of his own anarchist views and sent them, pretending that they were his own, to the German publisher.[8]

Schmid's hypothesis has both its adherents and opponents; at present its verification seems to be impossible. Anyway, B. Traven's (Ret Marut's) life in Mexico was as mysterious as his fate in Europe.

Traven Torsvan theory

Most researchers also identify B. Traven with the person named Berick Traven Torsvan who lived in Mexico from at least 1924. Torsvan rented a wooden house north of Tampico in 1924 where he often stayed and worked until 1931. Later, from 1930, he lived for 20 years in a house with a small restaurant on the outskirts of Acapulco from which he set off on his travels throughout Mexico.[21] As early as 1926, Torsvan took part as a photographer in an archeological expedition to the state of Chiapas led by Enrique Juan Palacios; one of the few photographs which may depict B. Traven, wearing a pith helmet, was taken during that expedition. Torsvan also travelled to Chiapas as well as to other regions of Mexico later, probably gathering materials for his books. He showed a lively interest in Mexican culture and history, following summer courses on the Spanish and Mayan languages, the history of Latin American literature and the history of Mexico at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in the years 1927 and 1928.[9]

In 1930 Torsvan received a foreigner's identification card as the North American engineer Traven Torsvan (in many sources, there also appears another first name of his: Berick or Berwick). It is known that B. Traven himself always claimed to be American. In 1933, the writer sent the English manuscripts of his three novels – The Death Ship, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and The Bridge in the Jungle – to the New York City publishing house Alfred A. Knopf for publication, claiming that these were the original versions of the novels and that the earlier published German versions were only translations of them. The Death Ship was published by Knopf in 1934; it was soon followed by further Traven books which appeared in the United States and the United Kingdom. However, comparison of the German and English versions of these books shows significant differences between them. The English texts are usually longer; in both versions there are also fragments which are missing in the other language. The problem is made even more complex by the fact that Traven's books published in English are full of Germanisms whereas those published in German full of Anglicisms.[8]

B. Traven's works also enjoyed a soaring popularity in Mexico itself. One person who contributed to this was Esperanza López Mateos, the sister of Adolfo López Mateos, later the President of Mexico, who translated eight books by Traven into Spanish from 1941. In subsequent years she acted as his representative in contacts with publishers and as the real owner of his copyright which she later transferred to his brothers.[9]

Filming of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Hal Croves theory

The commercial success of the novel The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, published in English by Knopf in 1935, induced the Hollywood Warner Bros. company to buy the film rights of the book in 1941. They signed up John Huston to direct it; however, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor caused an interruption in work on the film, which was renewed after the war.

In 1946, Huston arranged to meet B. Traven at the Bamer Hotel in Mexico City to discuss the details of the filming. However, instead of the writer, an unknown man turned up at the hotel and introduced himself as Hal Croves,[22] a translator from Acapulco and San Antonio. Croves showed an alleged power of attorney from B. Traven, in which the writer authorized him to decide on everything in connection with the filming of the novel on his behalf. Croves, instead of the writer, was also present at the next meeting in Acapulco and later, as a technical advisor, all the time on location during the shooting of the film in Mexico in 1947. At this point, the mysterious behaviour of the writer and his alleged agent made a great number of the crew members believe that Hal Croves was B. Traven himself in disguise. When the film became a big box office success after its premiere on 23 January 1948 and later won three Academy Awards, a real Traven fever broke out in the United States. This excitement was partly fuelled by Warner Bros. itself; American newspapers wrote at length about a mysterious author who took part incognito in the filming of the film based on his own book.[8]

Many biographers of B. Traven repeat the thesis that the director John Huston was also convinced that Hal Croves was B. Traven. This is not true. Huston denied identifying Hal Croves with Traven as early as 1948. Huston also brought the matter up in his autobiography,[23] published in 1980, where he wrote that he had been considering first that Croves might be Traven, but after observing his behaviour he had come to the conclusion that this was not the case. According to Huston, "Croves gave an impression quite unlike the one I had formed of Traven from reading his scripts and correspondence." However, according to Huston, Hal Croves played a double game during the shooting of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Asked by the crew members if he was Traven, he always denied, but he did so in such a way that his interlocutors came to the conclusion that he and B. Traven were indeed one and the same person.[8]

The "exposure" and vanishing of Torsvan

The media publicity which accompanied the premiere of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and the aura of mystery surrounding the author of the literary original of the film (rumour had it that Life magazine offered a reward of $5,000 for finding the real B. Traven[24]) induced a Mexican journalist named Luis Spota to try to find Hal Croves, who disappeared after the end of the shooting of the film in the summer of 1947. Thanks to information obtained from the Bank of Mexico, in July 1948, Spota found a man who lived under the name of Traven Torsvan near Acapulco. He formally ran an inn there; however, his shabby joint did not have many customers; Torsvan himself was a recluse, called El Gringo by his neighbours, which would confirm his American nationality. Investigating in official archives, Spota discovered that Torsvan had received a foreigner's identification card in Mexico in 1930 and a Mexican ID card in 1942; on both documents the date and place of birth was 5 March 1890 in Chicago. According to official records, Torsvan arrived in Mexico from the United States, crossing the border in Ciudad Juárez in 1914. Using partly dishonest methods (Spota bribed the postman who delivered letters to Torsvan), the journalist found out that Torsvan received royalties payable to B. Traven from Josef Wieder in Zurich; on his desk, he also found a book package from the American writer Upton Sinclair, which was addressed to B. Traven c/o Esperanza López Mateos. When Spota asked Torsvan directly whether he, Hal Croves and B. Traven are one and the same person, he denied this angrily; however, in the opinion of the journalist, Torsvan got confused in his explanations and finally admitted indirectly to being the writer.[8]

Spota published the results of his investigations in a long article in the newspaper Mañana on 7 August 1948. In reply to this, Torsvan published a denial in the newspaper Hoy on 14 August. He received Mexican citizenship on 3 September 1951.[8] A man named Traves Torstvan flew from Mexico City to Paris on Air France on 8 September 1953 and returned to Mexico City from Paris on 28 September of the same year.[25] On 10 October 1959, Traves Torsvan arrived in Houston, Texas from Mexico on a KLM airlines flight accompanied by his wife Rosa E. Torsvan, presumably Rosa Elena Luján. Torsvan states his citizenship as Mexican and his date and place of birth as 2 May 1890 (3 May in the typewritten version of the document) in Chicago, Illinois. Rose E. Torstvan states her date of birth as 6 April 1915 in Proginoso [sic], Yucatan.[26] These documents are evidence that Traven/Torsvan/Croves are one and the same person, and that rather than "disappearing," Torsvan took on his mother's supposed maiden name of Croves sometime after 1959.

B. Traven's agents and BT-Mitteilungen

Esperanza López Mateos had been cooperating with B. Traven since at least 1941 when she translated his first novel The Bridge in the Jungle into Spanish. Later she also translated seven other novels of his. Esperanza, the sister of Adolfo López Mateos, later the President of Mexico, played an increasingly important role in Traven's life. For example, in 1947, she went to Europe to represent him in contacts with his publishers; finally, in 1948, her name (along with Josef Wieder from Zurich) appeared as the copyright holder of his books. Wieder, as an employee of the Büchergilde Gutenberg book club, had already been cooperating with the writer since 1933. In that year, the Berlin-based book club Büchergilde Gutenberg, which had been publishing Traven's books so far, was closed by the Nazis after Adolf Hitler took power. Traven's books were forbidden in Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1945, and the author transferred the publication rights to the branch of Büchergilde in Zurich, Switzerland, where the publishers also emigrated. In 1939, the author decided to end his cooperation with Büchergilde Gutenberg; after this break, his representative became Josef Wieder, a former employee of the book club who had never met the writer personally. Esperanza López Mateos died, committing suicide, in 1951; her successor was Rosa Elena Luján, Hal Croves' future wife.[8]

In January 1951, Josef Wieder and Esperanza López Mateos, and after her death, Rosa Elena Luján, started publishing hectographically the periodical BT-Mitteilungen (BT-Bulletins), which promoted Traven's books and appeared till Wieder's death in 1960. According to Tapio Helen, the periodical used partly vulgar methods, often publishing obvious falsehoods, for example about the reward offered by Life magazine when it was already known that the reward was only a marketing trick. In June 1952, BT-Mitteilungen published Traven's "genuine" biography, in which it claimed that the writer had been born in the Midwestern United States to an immigrant family from Scandinavia, that he had never gone to school, had had to make his living from the age of seven and had come to Mexico as a ship boy on board a Dutch steamer when he was ten. The editors also repeated the thesis that B. Traven's books were originally written in English and only later translated into German by a Swiss translator.[8]

Return of Hal Croves

In the meantime, Hal Croves, who had disappeared after shooting the film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, appeared on the literary scene in Acapulco again. He acted as a writer and the alleged representative of B. Traven, on behalf of whom he negotiated the publication and filming of his books with publishers and film producers. Rosa Elena Luján became Croves' secretary in 1952, and they married in San Antonio, Texas, on 16 May 1957. After the wedding, they moved to Mexico City, where they ran the Literary Agency R.E. Luján. Following Josef Wieder's death in 1960, Rosa was the only copyright holder for Traven's books.[8]

In October 1959, Hal Croves and Rosa Elena Luján visited Germany to take part in the premiere of the film The Death Ship based on Traven's novel. During the visit reporters tried to induce Croves to admit to being Traven, but in vain. Such attempts ended without success also in the 1960s. Many journalists tried to get to Croves' home in Mexico City; but only very few were admitted to him by Rosa, who guarded the privacy of her already very aged, half blind and half deaf husband.[27] The articles and interviews with Croves always had to be authorized by his wife. Asked by journalists if he was Traven, Croves always denied or answered evasively, repeating Traven's sentence from the 1920s that the work and not the man should count.[8]

Hal Croves' death

Hal Croves died in Mexico City on 26 March 1969. On the same day, his wife announced at a press conference that her husband's real name was Traven Torsvan Croves, that he had been born in Chicago on 3 May 1890 to a Norwegian father Burton Torsvan and a mother Dorothy Croves of Anglo-Saxon descent and that he had also used the pseudonyms B. Traven and Hal Croves during his life. She read this information from her husband's will, which had been drawn up by him three weeks before his death (on 4 March). Traven Torsvan Croves was also the name on the writer's official death certificate; his ashes, following cremation, were scattered from an airplane above the jungle of Chiapas state.[8]

This seemed at first to be the definitive solution to the riddle of the writer's biography – B. Traven was, as he always claimed himself, an American, not the German Ret Marut. However, the 'solution' proved fleeting: some time after Croves' death,[28] his widow gave another press announcement in which she claimed that her husband had authorized her to reveal the whole truth about his life, including facts which he had omitted from his will. The journalists heard that Croves had indeed been the German revolutionary named Ret Marut in his youth, which reconciled both the adherents of the theory of the Americanness and the proponents of the hypothesis about the Germanness of the writer. Rosa Elena Luján gave more information about these facts in her interview for the International Herald Tribune on 8 April 1969, where she claimed that her husband's parents had emigrated from the United States to Germany some time after their son's birth. In Germany, her husband published the successful novel The Death Ship, following which he went to Mexico for the first time, but returned to Germany to edit an anti-war magazine in the country "threatened by the emerging Nazi movement". He was sentenced to death, but managed to escape and went to Mexico again.[8]

On the other hand, the hypothesis of B. Traven's Germanness seems to be confirmed by Hal Croves' extensive archive, to which his widow granted access to researchers sporadically until her death in 2009. Rolf Recknagel conducted research into it in 1976, and Karl Guthke in 1982. These materials include train tickets and banknotes from different East-Central European countries, possibly keepsakes Ret Marut retained after his escape from Germany after the failed revolution in Bavaria in 1919. A very interesting document is a small notebook with entries in the English language. The first entry is from 11 July 1924, and on 26 July the following significant sentence appeared in the notebook: "The Bavarian of Munich is dead". The writer might have started this diary on his arrival in Mexico from Europe, and the above note could have expressed his willingness to cut himself from his European past and start a new existence as B. Traven.[8]

Other theories

The above hypotheses, identifying B. Traven with Hal Croves, Traven Torsvan, Ret Marut and possibly Otto Feige, are not the only ones concerning the writer's identity which have appeared since the mid-1920s. Some of them are relatively well-founded; others are quite fantastic and incredible. Some of the most common hypotheses, apart from those already mentioned, are presented below:

- B. Traven was two or more persons (Hal Croves/Traven Torsvan and Ret Marut) who worked in collaboration, according to John Huston.[23]

- B. Traven was German; however, he did not come from Schwiebus but from northern Germany, the region between Hamburg and Lübeck. It is possible to conclude this on the basis of a preserved cassette, recorded by his stepdaughter Malú Montes de Oca (Rosa Luján's daughter), on which he sings two songs in Low German, a dialect of the German language, with some language features which are typical not only of this region. Torsvan is a relatively common name in this area, through which also the River Trave runs. In the neighbourhood there are also such places as Traventhal, Travenhorst and Travemünde (Lübeck's borough) – a large ferry harbour on the Baltic Sea.[3][29]

- B. Traven was an illegitimate son of the German Emperor Wilhelm II. Such a hypothesis was presented by Gerd Heidemann, a reporter from Stern magazine, who claimed that he had obtained this information from Rosa Luján, Hal Croves' wife. Later, however, the journalist distanced himself from this hypothesis. Heidemann himself compromised himself through his complicity in the falsification of Hitler's diaries in the 1980s.[29][30][31]

- B. Traven was the American writer Jack London, who faked his death and then moved to Mexico and continued writing his books.[29]

- B. Traven was the pseudonym of the American writer Ambrose Bierce, who went to Mexico in 1913 to take part in the Mexican Revolution where he disappeared without a trace.[29] Note that Bierce was born in 1842, which would have made him 83 at the time of Traven's first published work, and 127 at the time of his death in 1969.

- B. Traven was the pseudonym of Adolfo López Mateos, the President of Mexico (1958–1964). The source of this rumour was probably the fact that Esperanza López Mateos, Adolfo's sister, was Traven's representative in his contacts with publishers and a translator of his books into Spanish. Some even claimed that the books published under the pen name B. Traven were written by Esperanza herself.[30]

- The pseudonym B. Traven was used by August Bibelje, a former customs officer from Hamburg, gold prospector and adventurer. This hypothesis was also presented – and rejected – by the journalist Gerd Heidemann. According to Heidemann, Ret Marut met Bibelje after his arrival in Mexico and used his experiences in such novels as The Cotton Pickers, The Death Ship and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. However, Bibelje himself returned to Europe later and died during the Spanish Civil War in 1937.[30]

List of works

B. Traven – Stand-alone works

- The Cotton Pickers (1927; retitled from The Wobbly) ISBN 1-56663-075-4

- The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1927; first English pub. 1935) ISBN 0-8090-0160-8

- The Death Ship: The Story of an American Sailor (1926; first English pub. 1934) ISBN 1-55652-110-3

- The White Rose (1929; first full English pub 1979) ISBN 0-85031-370-8

- The Night Visitor and Other Stories (English pub. 1967)) ISBN 1-56663-039-8

- The Bridge in the Jungle (1929; first English pub. 1938) ISBN 1-56663-063-0

- Land des Frühlings (1928) – travel book – untranslated

- Aslan Norval (1960) ISBN 978-3-257-05016-5 – untranslated

- Stories by the Man Nobody Knows (1961)

- The Kidnapped Saint and Other Stories (1975)

- The Creation of the Sun and the Moon (1968)

B. Traven – The Jungle Novels

- The Carreta (1931, released in Germany 1930) ISBN 1-56663-045-2

- Government (1931) ISBN 1-56663-038-X

- March to the Monteria (a.k.a. March To Caobaland) (1933) ISBN 1-56663-046-0

- Trozas (1936) ISBN 1-56663-219-6

- The Rebellion of the Hanged (1936; first English pub. 1952) ISBN 1-56663-064-9

- A General from the Jungle (1940) ISBN 1-56663-076-2

B. Traven – Collected stories

- Canasta de cuentos mexicanos (or Canasta of Mexican Stories, 1956, Mexico City, translated from the English by Rosa Elena Luján) ISBN 968-403-320-6

Films based on works by B. Traven

- Kuolemanlaiva (TV movie), 1983

- The Bridge in the Jungle, 1971

- Die Baumwollpflücker (TV series), 1970

- Au verre de l'amitié, 1970

- Días de otoño (story "Frustration"),1963

- Rosa Blanca (novel La Rosa Blanca), 1961

- Macario (story "The Third Guest"), 1960

- The Death Ship, 1959

- Der Banditendoktor (TV movie), 1957

- The Argonauts (Episode of Cheyenne TV series), 1955

- Canasta de cuentos mexicanos, 1955

- The Rebellion of the Hanged, 1954

- The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, 1948

Notable illustrations of works by B. Traven

- Dödsskeppet (The Death Ship), Atlantis, Stockholm 1978, and Het dodenschip, Meulenhoff, Amsterdam 1978. Inkdrawings by the Swedish artist Torsten Billman. Unpublished in English.

Works by Ret Marut

- To the Honorable Miss S... and other stories (1915–19; English publication 1981) ISBN 0-88208-131-4

- Die Fackel des Fürsten – Novel (Nottingham: Edition Refugium 2009) ISBN 0-9506476-2-4;ISBN 978-0-9506476-2-3

- Der Mann Site und die grünglitzernde Frau – Novel (Nottingham: Edition Refugium 2009) ISBN 0-9506476-3-2; ISBN 978-0-9506476-3-0

References

- ↑ Jesse Pearson (2009) The Mystery Of B. Traven, Vice.com, accessed 25 Jan 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "B. Traven's works". Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Rolf Cantzen, Die Revolution findet im Roman statt. Der politische Schriftsteller B. Traven (SWR Radio broadcast and its transcript". Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Lexikon der Anarchie". Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ↑ B. Traven, The Death Ship, p. 119, quoted from: Richard E. Mezo, A study of B. Traven's fiction: the journey to Solipaz, Mellen Research University Press, San Francisco, 1993, p. 20.

- ↑ The writer also expressed this thought in another famous quotation: If one cannot get to know the human through his works, then either the human is worthless, or his works are worthless (Wenn der Mensch in seinen Werken nicht zu erkennen ist, dann ist entweder der Mensch nichts wert oder seine Werke sind nichts wert). Quotation from: Günter Dammann (ed.), B. Travens Erzählwerk in der Konstellation von Sprache und Kulturen, Würzburg, Königshausen & Neumann, 2005, p. 311.

- 1 2 Jan-Christoph Hauschild, "B. Traven – die unbekannten Jahre", Zürich: Edition Voldemeer 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "Tapio Helen, B. Traven's Identity Revisited". Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "B. Traven's biography". Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ↑ Rolf Recknagel, B. Traven. Beiträge zur Biografie, Köln, Röderberg Verlag, 1991.

- ↑ James Goldwasser tried to reconstruct Ret Marut's detailed biography (till 1923) in the article "Ret Marut: The Early B. Traven", published in The Germanic Review in June 1993. See the online version of the article on the website .

- ↑ Will Wyatt, The Secret of the Sierra Madre: The Man who was B. Traven, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1985, ISBN 978-0-15-679999-7.

- ↑ http://www.sfmuseum.net/hist11/papersons.html

- ↑ Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of successor and related bodies. The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England, via ancestry.com

- ↑ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists.; Class: BT26; Piece: 736; Item: 3, via ancestry.com under mis-transcribed forename "Rox" [sic].

- ↑ Library and Archives Canada. Form 30A, 1919-1924 (Ocean Arrivals). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Library and Archives Canada, n.d.. RG 76. Department of Employment and Immigration Fonts. Microfilm Reels: T-14939 to T-15248, via ancestry.com.

- ↑ Karl S. Guthke, B. Traven. Biografie eines Rätsels, Frankfurt am Main, Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1987.

- ↑ Cf. an article in Vorwärts of 18 March 1982.

- ↑ Cf. the article on Linn Gale in the archive of The New York Times of 18 September 1921 .

- ↑ Gerard Gale, Der geheimnisvolle B. Traven, in: Tages-Anzeiger, 2 November 1963 – 4 January 1964.

- ↑ B. Traven versteckt sich in Acapulco – STOCKPRESS.de STOCKPRESS.de

- ↑ The name Hal Croves had already appeared earlier, for the first time in 1944, on the envelope of a letter addressed to him by Esperanza López Mateos

- 1 2 John Huston, An Open Book, Vaybrama N.V., 1980.

- ↑ . The rumour was not true. Rafael Arles Ramirez, who was responsible for the promotion of B. Traven's books in Mexico, admitted in 1956 that he had invented and circulated the story to boost interest in the writer's novels.

- ↑ Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1820-1897. Microfilm Publication M237, 675 rolls. NAI: 6256867. Records of the U.S. Customs Service, Record Group 36. National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Year: 1953; Arrival: Mexico; Microfilm Serial: T715, 1897-1957; Microfilm Roll: Roll 8371; Line: 4; Page Number: 246, via ancestry.com.

- ↑ The National Archives at Washington, D.C.; Washington, D.C.; Series Title: Passenger and Crew Manifests of Airplanes Arriving at Houston, Texas; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004, via ancestry.com

- ↑ Croves underwent surgery for progressive deafness in Berlin in 1959.

- ↑ Different sources give different dates of revealing the information below. See Tapio Helen's article.

- 1 2 3 4 "Frank Nordhausen, Der Fremde in der Calle Mississippi. Article from the Berliner Zeitung, of 11 March 2000". Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Peter Neuhauser, Der Mann, der sich B. Traven nennt. Article from Die Zeit of 23 May 1967". Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ↑ Heidemann also described his quest for Traven in the book Postlagernd Tampico – Die abenteuerliche Suche nach B. Traven, Blanvalet, München, 1977, ISBN 3-7645-0591-5.

Bibliography

- Baumann, Michael L. B. Traven: An introduction, ISBN 978-0-8263-0409-4

- Baumann, Michael L. Mr. Traven, I Presume?, AuthorHouse, online 1997, ISBN 1-58500-141-4

- Chankin, Donald O. Anonymity and Death: The Fiction of B. Traven, ISBN 978-0-271-01190-5

- Czechanowsky, Thorsten. 'Ich bin ein freier Amerikaner, ich werde mich beschweren'. Zur Destruktion des American Dream in B. Travens Roman 'Das Totenschiff' ' , in: Jochen Vogt/Alexander Stephan (Hg.): Das Amerika der Autoren, München: Fink 2006.

- Czechanowsky, Thorsten. Die Irrfahrt als Grenzerfahrung. Überlegungen zur Metaphorik der Grenze in B. Travens Roman 'Das Totenschiff' in: mauerschau 1/2008, pp. 47–58.

- Dammann, Günter (ed.), B. Travens Erzählwerk in der Konstellation von Sprache und Kulturen, Würzburg, Königshausen & Neumann, 2005; ISBN 3-8260-3080-X

- Giacopini, Vittorio. L'arte dell'inganno, Fandango libri 2001 (in Italian) ISBN 978-88-6044-191-1

- Guthke, Karl S. B.Traven: The Life Behind the Legends, ISBN 978-1-55652-132-4

- Guthke, Karl S. B. Traven. Biografie eines Rätsels, Frankfurt am Main, Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1987, ISBN 3-7632-3268-0

- Guthke, Karl S. "Das Geheimnis um B. Traven entdeckt" – und rätselvoller denn je, Frankfurt am Main, Büchergilde Gutenberg, 1984, ISBN 3-7632-2877-2

- Hauschild, Jan-Christoph: B. Traven – Die unbekannten Jahre. Edition Voldemeer, Zürich / Springer, Wien, New York 2012, ISBN 978-3-7091-1154-3.

- Heidemann, Gerd. Postlagernd Tampico. Die abenteuerliche Suche nach B. Traven, München, Blanvalet, 1977, ISBN 3-7645-0591-5

- Mezo, Richar Eugene. A study of B. Traven's fiction – the journey to Solipaz, San Francisco, Mellen Research University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-7734-9838-9

- Pateman, Roy. The Man Nobody Knows: The Life and Legacy of B. Traven, ISBN 978-0-7618-2973-7

- Raskin, Jonah, My Search for B. Traven, ISBN 978-0-416-00741-1

- Recknagel, Rolf. B. Traven. Beiträge zur Biografie, Köln, Röderberg Verlag, 1991, ISBN 978-3-87682-478-9

- Schürer, Ernst and Jenkins, P. B. Traven: Life and Work, ISBN 978-0-271-00382-5

- Stone, Judy, The Mystery of B. Traven, ISBN 978-0-595-19729-3.

- Thunecke, Jörg (ed.) B. Traven the Writer / Der Schriftsteller B. Traven, Edition Refugium: Nottingham 2003, ISBN 0-9542612-0-8, ISBN 0-9506476-5-9, ISBN 978-0-9506476-5-4

- Wyatt, Will. The Secret of the Sierra Madre: The Man who was B. Traven, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1985, ISBN 978-0-15-679999-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to B. Traven. |

- B. Traven Website of the International B. Traven Society

- Helen Tapio B. Traven's Identity Revisited University of Helsinki, Department of History

- Petri Liukkonen. "B. Traven". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- B. Traven, from the Anarchist Encyclopedia

- B. Traven – An Anti-Biography, biography with pictures from libcom.org

- Frank Nordhausen, Der Fremde in der Calle Mississippi Berliner Zeitung of 11 March 2000

- B. Traven in Lexikon der Anarchie

- The B. Traven Collections at UC Riverside Libraries

- Kurt Tucholsky, B. Traven Kurt Tucholsky about Traven (review), Die Weltbühne of 25 November 1930

- Peter Neuhauser, Der Mann, der sich B. Traven nennt Die Zeit of 12 May 1967

- Rolf Cantzen, Die Revolution findet im Roman statt. Der politische Schriftsteller B. Traven SWR Radio broadcast and ist transcript

- Rolf Raasch, B. Traven: ein deutsch-mexikanischer Mythos

- Larry Rohter, His Widow Reveals Much Of Who B. Traven Really Was The New York Times of 25 June 1990

- James Goldwasser, Ret Marut – The Early B. Traven

- B. Traven – Voice of the Hanged by Chris Harman

- Jan-Christoph Hauschild: Ein Virtuose des Verschwindens. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, August 30, 2009, p. 30.

- Jan-Christoph Hauschild: B. Traven – wer ist dieser Mann?. In: FAZ, July 17, 2009

- The historical residence of Otto Feige aka Ret Marut aka B. Traven in Świebodzin, Poland.