Music for the Requiem Mass

The Requiem Mass is notable for the large number of musical compositions that it has inspired, including settings by Mozart, Verdi, Bruckner, Dvořák, Fauré and Duruflé. Originally, such compositions were meant to be performed in liturgical service, with monophonic chant. Eventually the dramatic character of the text began to appeal to composers to an extent that they made the requiem a genre of its own, and the compositions of composers such as Verdi are essentially concert pieces rather than liturgical works.

Common texts

The following are the texts that have been set to music. Note that the Libera Me and the In Paradisum are not part of the text of the Catholic Mass for the Dead itself, but a part of the burial rite that immediately follows. In Paradisum was traditionally said or sung as the body left the church, and the Libera Me is said/sung at the burial site before interment. These became included in musical settings of the Requiem in the 19th century as composers began to treat the form more liberally.

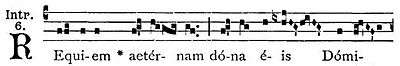

Introit (4 Esdras 2:34–35; Psalm 64:2–3)

|

Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine: |

Kyrie eleison

This is as the Kyrie in the Ordinary of the Mass:

|

Kyrie, eleison. |

Lord, have mercy. |

This is Greek (Κύριε ἐλέησον, Χριστὲ ἐλέησον, Κύριε ἐλέησον). Each utterance is sung three times, though sometimes that is not the case when sung polyphonically.

Gradual (4 Esdras 2:34–35; Psalm 111:7)

|

Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine: |

Eternal rest give unto them, O Lord; |

Tract

|

Absolve, Domine, |

Absolve, O Lord, |

Sequence

A sequence is a liturgical poem sung, when used, after the Tract (or Alleluia, if present). The sequence employed in the Requiem, Dies Irae, attributed to Thomas of Celano (c. 1200 – c. 1260–1270), has been called "the greatest of hymns", worthy of "supreme admiration".[1] The Latin text below is taken from the Requiem Mass in the 1962 Roman Missal. The first English version below, translated by William Josiah Irons in 1849,[2] replicates the rhyme and metre of the original. The second English version is a more formal equivalence.

| 1 | Dies iræ, dies illa, Solvet sæclum in favilla: Teste David cum Sibylla. |

Day of wrath and doom impending, David's word with Sibyl's blending, Heaven and earth in ashes ending. |

The day of wrath, that day will dissolve the world in ashes, David being witness along with the Sibyl. |

| 2 | Quantus tremor est futurus, Quando iudex est venturus, Cuncta stricte discussurus! |

Oh, what fear man's bosom rendeth, When from heaven the Judge descendeth, On whose sentence all dependeth. |

How great will be the quaking, when the Judge will come, investigating everything strictly. |

| 3 | Tuba, mirum spargens sonum Per sepulchra regionum, Coget omnes ante thronum. |

Wondrous sound the trumpet flingeth, Through earth's sepulchers it ringeth, All before the throne it bringeth. |

The trumpet, scattering a wondrous sound through the sepulchres of the regions, will summon all before the throne. |

| 4 | Mors stupebit, et natura, Cum resurget creatura, Iudicanti responsura. |

Death is struck, and nature quaking, All creation is awaking, To its Judge an answer making. |

Death and nature will marvel, when the creature will rise again, to respond to the Judge. |

| 5 | Liber scriptus proferetur, In quo totum continetur, Unde mundus iudicetur. |

Lo, the book exactly worded, Wherein all hath been recorded, Thence shall judgement be awarded. |

The written book will be brought forth, in which all is contained, from which the world shall be judged. |

| 6 | Iudex ergo cum sedebit, Quidquid latet, apparebit: Nil inultum remanebit. |

When the Judge His seat attaineth, And each hidden deed arraigneth, Nothing unavenged remaineth. |

When therefore the Judge will sit, whatever lies hidden will appear: nothing will remain unpunished. |

| 7 | Quid sum miser tunc dicturus? Quem patronum rogaturus, Cum vix iustus sit securus? |

What shall I, frail man, be pleading? Who for me be interceding When the just are mercy needing? |

What then will I, poor wretch [that I am], say? Which patron will I entreat, when [even] the just may [only] hardly be sure? |

| 8 | Rex tremendæ maiestatis, Qui salvandos salvas gratis, Salva me, fons pietatis. |

King of majesty tremendous, Who dost free salvation send us, Fount of pity, then befriend us. |

King of fearsome majesty, Who freely savest those that are to be saved, save me, O font of mercy. |

| 9 | Recordare, Iesu pie, Quod sum causa tuæ viæ: Ne me perdas illa die. |

Think, kind Jesus, my salvation Caused Thy wondrous Incarnation, Leave me not to reprobation. |

Remember, merciful Jesus, that I am the cause of Thy way: lest Thou lose me in that day. |

| 10 | Quærens me, sedisti lassus: Redemisti Crucem passus: Tantus labor non sit cassus. |

Faint and weary Thou hast sought me, On the Cross of suffering bought me, Shall such grace be vainly brought me? |

Seeking me, Thou sattest tired: Thou redeemedst [me], having suffered the Cross: let not so much hardship be in vain. |

| 11 | Iuste iudex ultionis, Donum fac remissionis Ante diem rationis. |

Righteous Judge, for sin's pollution Grant Thy gift of absolution, Ere that day of retribution. |

Just Judge of vengeance, make a gift of remission before the day of reckoning. |

| 12 | Ingemisco, tamquam reus: Culpa rubet vultus meus: Supplicanti parce, Deus. |

Guilty now I pour my moaning, All my shame with anguish owning, Spare, O God, Thy suppliant groaning. |

I sigh, like the guilty one: my face reddens in guilt: Spare the supplicating one, O God. |

| 13 | Qui Mariam absolvisti, Et latronem exaudisti, Mihi quoque spem dedisti. |

Through the sinful woman shriven, Through the dying thief forgiven, Thou to me a hope hast given. |

Thou who absolvedst Mary, and heardest the robber, gavest hope to me, too. |

| 14 | Preces meæ non sunt dignæ; Sed tu bonus fac benigne, Ne perenni cremer igne. |

Worthless are my prayers and sighing, Yet, good Lord, in grace complying, Rescue me from fires undying. |

My prayers are not worthy: but do Thou, [who art] good, graciously grant that I not be burned up by the everlasting fire. |

| 15 | Inter oves locum præsta. Et ab hædis me sequestra, Statuens in parte dextra. |

With Thy sheep a place provide me, From the goats afar divide me, To Thy right hand do Thou guide me. |

Grant me a place among the sheep, and take me out from among the goats, setting me on the right side. |

| 16 | Confutatis maledictis, Flammis acribus addictis: Voca me cum benedictis. |

When the wicked are confounded, Doomed to flames of woe unbounded, Call me with Thy saints surrounded. |

Once the cursed have been silenced, sentenced to acrid flames: Call Thou me with the blessed. |

| 17 | Oro supplex et acclinis, Cor contritum quasi cinis: Gere curam mei finis. |

Low I kneel with heart's submission, See, like ashes, my contrition, Help me in my last condition. |

[Humbly] kneeling and bowed I pray, [my] heart crushed as ashes: take care of my end. |

| 18 | Lacrimosa dies illa, Qua resurget ex favilla Iudicandus homo reus: Huic ergo parce, Deus. |

Ah! that day of tears and mourning, From the dust of earth returning, Man for judgment must prepare him, Spare, O God, in mercy spare him. |

Tearful [will be] that day, on which from the glowing embers will arise the guilty man who is to be judged. Then spare him, O God. |

| 19 | Pie Iesu Domine, Dona eis requiem. Amen. |

Lord all-pitying, Jesus blest, Grant them Thine eternal rest. Amen. |

Merciful Lord Jesus, grant them rest. Amen. |

Offertory

|

Domine Iesu Christe, Rex gloriæ, |

O Lord Jesus Christ, King of glory, |

|

Hostias et preces tibi, Domine, |

We offer to Thee, O Lord, |

Sanctus

This is as the Sanctus prayer in the Ordinary of the Mass:

|

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus |

Holy, holy, holy, |

Agnus Dei

This is as the Agnus Dei in the Ordinary of the Mass, but with the petitions miserere nobis changed to dona eis requiem, and dona nobis pacem to dona eis requiem sempiternam:

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi: dona eis requiem. |

Lamb of God, Who takest away the sins of the world, grant them rest. |

Communion (4 Esdras 2:35 & 34)

|

Lux æterna luceat eis, Domine: |

As mentioned above, there is no Gloria, Alleluia or Credo in these musical settings.

Pie Jesu

Some extracts too have been set independently to music, such as Pie Jesu in the settings of Dvořák, Fauré, Duruflé and John Rutter.

The Pie Jesu consists of the final words of the Dies Irae followed by the final words of the Agnus Dei.

|

Pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem. |

Merciful Lord Jesus, grant them rest; |

Musical Requiem settings sometimes include passages from the "Absolution at the bier" (Absolutio ad feretrum) or "Commendation of the dead person" (referred to also as the Absolution of the dead), which in the case of a funeral, follows the conclusion of the Mass.

Libera Me

|

Libera me, Domine, de morte æterna, in die illa tremenda: |

Deliver me, O Lord, from death eternal in that awful day. |

In paradisum

|

In paradisum deducant te Angeli: |

May the Angels lead thee into paradise: |

History of musical compositions

For many centuries the texts of the requiem were sung to Gregorian melodies. The Requiem by Johannes Ockeghem, written sometime in the later half of the 15th century, is the earliest surviving polyphonic setting. There was a setting by the elder composer Dufay, possibly earlier, which is now lost: Ockeghem's may have been modelled on it.[3] Many early compositions employ different texts that were in use in different liturgies around Europe before the Council of Trent set down the texts given above. The requiem of Brumel, circa 1500, is the first to include the Dies Iræ. In the early polyphonic settings of the Requiem, there is considerable textural contrast within the compositions themselves: simple chordal or fauxbourdon-like passages are contrasted with other sections of contrapuntal complexity, such as in the Offertory of Ockeghem's Requiem.[3]

In the 16th century, more and more composers set the Requiem mass. In contrast to practice in setting the Mass Ordinary, many of these settings used a cantus-firmus technique, something which had become quite archaic by mid-century. In addition, these settings used less textural contrast than the early settings by Ockeghem and Brumel, although the vocal scoring was often richer, for example in the six-voice Requiem by Jean Richafort which he wrote for the death of Josquin des Prez.[3] Other composers before 1550 include Pedro de Escobar, Antoine de Févin, Cristóbal Morales, and Pierre de La Rue; that by La Rue is probably the second oldest, after Ockeghem's.

Over 2,000 Requiem compositions have been composed to the present day. Typically the Renaissance settings, especially those not written on the Iberian Peninsula, may be performed a cappella (i.e. without necessary accompanying instrumental parts), whereas beginning around 1600 composers more often preferred to use instruments to accompany a choir, and also include vocal soloists. There is great variation between compositions in how much of liturgical text is set to music.

Most composers omit sections of the liturgical prescription, most frequently the Gradual and the Tract. Fauré omits the Dies iræ, while the very same text had often been set by French composers in previous centuries as a stand-alone work.

Sometimes composers divide an item of the liturgical text into two or more movements; because of the length of its text, the Dies iræ is the most frequently divided section of the text (as with Mozart, for instance). The Introit and Kyrie, being immediately adjacent in the actual Roman Catholic liturgy, are often composed as one movement.

Musico-thematic relationships among movements within a Requiem can be found as well.

Requiem in concert

Beginning in the 18th century and continuing through the 19th, many composers wrote what are effectively concert works, which by virtue of employing forces too large, or lasting such a considerable duration, prevent them being readily used in an ordinary funeral service; the requiems of Gossec, Berlioz, Verdi, and Dvořák are essentially dramatic concert oratorios. A counter-reaction to this tendency came from the Cecilian movement, which recommended restrained accompaniment for liturgical music, and frowned upon the use of operatic vocal soloists.

Notable compositions

Many composers have composed Requiems. Some of the most notable include the following (in chronological order):

- Ockeghem: Requiem, the earliest to survive, written sometime in the mid-to-late 15th century

- Victoria: Requiem of 1603, (part of a longer Office for the Dead)

- Jan Dismas Zelenka: Requiem in D Minor ZWV 48 After Augustus the Strong Circa 1730

- Mozart: Requiem in D minor, K. 626 (1791: Mozart died before its completion; Franz Xaver Süssmayr's completion is often used)

- Antonio Salieri: Requiem (1804) (played at his funeral on May 7, 1825)

- Cherubini: Requiem in C minor (1815)

- Berlioz: Grande Messe des morts (1837)

- Brahms: A German Requiem, Op. 45, based on passages from Luther's Bible (1869)

- Verdi: Requiem (1874)

- Dvořák: Requiem, Op. 89 (1890)

- Fauré: Requiem in D minor, Op. 48 (1890)

- Duruflé: Requiem, Op. 9, based almost exclusively on the chants from the Graduale Romanum (1947)

- Britten: War Requiem, Op. 66, which incorporated poems by Wilfred Owen (1962)

- Stravinsky: Requiem Canticles (1966)

- Bernd Alois Zimmermann: Requiem für einen jungen Dichter (1969), which incorporates poetic, political and philosophical text that shaped his lifetime

- Penderecki: Polish Requiem (1984, revised 1993 and 2005)

- Lloyd Webber: Requiem (1985)

- Rutter: Requiem, includes Psalm 130, Psalm 23 and words from the Book of Common Prayer (1985)

- See also: Category:Requiems

Other composers

Renaissance

- Giovanni Francesco Anerio

- Gianmatteo Asola

- Giulio Belli

- Antoine Brumel

- Manuel Cardoso

- Joan Cererols

- Pierre Certon

- Clemens non Papa

- Guillaume Dufay (lost)

- Pedro de Escobar

- Antoine de Févin

- Francisco Guerrero

- Jacobus de Kerle

- Orlande de Lassus

- Duarte Lobo

- Jean Maillard

- Jacques Mauduit

- Manuel Mendes

- Cristóbal de Morales

- Johannes Ockeghem (the earliest to survive)

- Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

- Costanzo Porta

- Johannes Prioris

- Jean Richafort

- Pedro Rimonte

- Pierre de la Rue

- Claudin de Sermisy

- Jacobus Vaet

- Tomás Luis de Victoria

Baroque

- Giovanni Francesco Anerio

- Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber

- André Campra

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier

- Johann Joseph Fux

- Jean Gilles

- Antonio Lotti (Requiem in F Major)

- Benedetto Marcello (Requiem in the Venetian Manner)

- Claudio Monteverdi (lost)

- Michael Praetorius

- Heinrich Schütz

- Andrzej Siewiński

- Jan Dismas Zelenka

Classical period

- Luigi Cherubini

- Domenico Cimarosa

- Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

- Joseph Leopold Eybler

- Florian Leopold Gassmann

- François-Joseph Gossec

- Johann Adolf Hasse

- Michael Haydn

- Georg von Pasterwitz

- Joseph Martin Kraus

- Andrea Lucchesi

- Giovanni Battista Martini

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- José Maurício Nunes Garcia

- Ignaz Pleyel

- Antonio Salieri

- Osip Kozlovsky

Romantic era

- Hector Berlioz

- João Domingos Bomtempo

- Johannes Brahms

- Anton Bruckner, Requiem in D minor[4]

- Ferruccio Busoni

- Carl Czerny

- Gaetano Donizetti

- Antonín Dvořák

- Gabriel Fauré

- Charles Gounod

- Franz Lachner

- Franz Liszt

- Giacomo Puccini [Introit only]

- Max Reger Hebbel Requiem, Lateinisches Requiem (fragment)

- Antonín Rejcha

- Camille Saint-Saëns

- Robert Schumann

- Franz von Suppé

- Charles Villiers Stanford

- Giuseppe Verdi

- Richard Wetz

- See also: Messa per Rossini

20th century

- Mark Alburger

- Malcolm Archer

- Vyacheslav Artyomov

- John Baboukis’s Requiem Mass for G.K. Chesterton (1986)[5]

- Osvaldas Balakauskas

- Benjamin Britten

- Sylvano Bussotti's "Rara Requiem" (1969)

- Michel Chion

- Vladimir Dashkevich

- Stephen DeCesare's "Requiem"

- James DeMars: An American Requiem

- Edison Denisov

- Alfred Desenclos (1963)

- Felix Draeseke (1910)

- Ralph Dunstan

- Maurice Duruflé

- Lorenzo Ferrero's Introito, part of the Requiem per le vittime della mafia

- Gerald Finzi's Requiem da camera

- John Foulds "A World Requiem"

- Howard Goodall's "Eternal Light: A Requiem"

- William Harper "Requiem"[6]

- Hans Werner Henze

- Frigyes Hidas

- Herbert Howells

- Sigurd Islandsmoen

- Karl Jenkins

- Dmitry Kabalevsky (1962)

- Volker David Kirchner

- Ståle Kleiberg

- Joonas Kokkonen

- Cyrillus Kreek

- Huub de Lange

- Morten Lauridsen "Lux Aeterna"

- Philip Ledger

- Kamilló Lendvay

- György Ligeti (1965)

- Nils Lindberg

- Andrew Lloyd Webber

- Fernando Lopes-Graça

- Roman Maciejewski

- Bruno Maderna (1946)

- Frank Martin

- Jean-Christian Michel

- Otto Olsson (1903)

- Ildebrando Pizzetti (1968)

- Jocelyn Pook

- Zbigniew Preisner

- Robert Rønnes

- John Rutter (1985)

- Joseph Ryelandt

- Shigeaki Saegusa

- Alfred Schnittke

- Giovanni Sgambati (1901)

- Valentin Silvestrov

- Fredrik Sixten

- Robert Steadman

- Igor Stravinsky

- Toru Takemitsu

- John Tavener

- Virgil Thomson

- Erkki-Sven Tüür

- Malcolm Williamson

- Bernd Alois Zimmermann: Requiem für einen jungen Dichter (1969)

21st century

- John Starr Alexander "Requiem" 2001

- Lera Auerbach "Russian Requiem"

- Leonardo Balada

- Troy Banarzi

- Virgin Black

- Jamie Brown "A Cornish Requiem / Requiem Kernewek"

- Paul Carr "Requiem for an Angel"

- Bob Chilcott[7]

- Richard Danielpour: "An American Requiem"

- Stephen DeCesare "Missa De Profunctis"

- Bradley Ellingboe

- Mohammed Fairouz "Requiem Mass"

- Carlo Forlivesi

- Eliza Gilkyson, arr. by Craig Hella Johnson "Requiem"

- Howard Goodall "Eternal Light"

- Steve Gray "Requiem For Choir and Big Band"

- Patrick Hawes "Lazarus Requiem"[8]

- Tyzen Hsiao

- Karl Jenkins "The Armed Man" (2000) & "Requiem" (2004)

- Rami Khalifé (2013)

- Iver Kleive

- Fan-Long Ko

- Thierry Lancino

- György Ligeti (2006)

- Clint Mansell, (Theme from Requiem For A Dream aka 'Lux Aeterna')

- Christopher Rouse

- Carl Rütti

- Keiki Kobayashi, (Theme from Ace Combat 04: Shattered Skies aka Megalith -Agnus Dei-)

- Kentaro Sato

- Mattias Sköld

- Somtow Sucharitkul

- John Tavener (Heartbeat, aka 'Prayer of the Heart' written for Björk)

- Chris Williams "Tsunami Requiem"

- Mack Wilberg

- David Crowder Band "Give Us Rest"

- António Pinho Vargas

- Ehsan Saboohi "Phonemes Requiem" (2014-2015)[9]

Requiem by language (other than Latin)

English with Latin

- Benjamin Britten: War Requiem

- Richard Danielpour: An American Requiem

- Howard Goodall: "Eternal Light"

- Patrick Hawes "Lazarus Requiem"[8]

- Herbert Howells

- John Rutter: Requiem

- Fredrik Sixten

- Somtow Sucharitkul

- Mack Wilberg

Cornish

- Jamie Brown: A Cornish Requiem / Requiem Kernewek

Estonian

- Cyrillus Kreek: Estonian Requiem

German

- Johannes Brahms: Ein deutsches Requiem

- Michael Praetorius

- Max Reger Hebbel Requiem

- Franz Schubert

- Heinrich Schütz

French, Greek, with Latin

French, English, German with Latin

Latin and Japanese

Latin and German and others

Latin and Polish

Russian

- Lera Auerbach – Russian Requiem, on Russian Orthodox sacred text and poetry

- Vladimir Dashkevich – Requiem (Text by Anna Akhmatova)

- Elena Firsova – Requiem, Op.100 (Text by Anna Akhmatova)

- Dmitri Kabalevsky – War Requiem (Text by Robert Rozhdestvensky)

- Sergei Taneyev – Cantata John of Damascus, Op.1 (Text by Alexey Tolstoy)

Taiwanese

- Tyzen Hsiao – Ilha Formosa: Requiem for Formosa's Martyrs, 2001 (Text by Min-yung Lee, 1994)

- Fan-Long Ko – 2-28 Requiem, 2008. (Text by Li Kuei-Hsien)

Persian, Farsi

- Ehsan Saboohi – Phonemes Requiem (For four Soloists, mixed Chorus, Didgeridoo, prepared Tombak, Electronics, Computer)[10]

Nonlinguistic

- Luciano Berio's Requies: in memoriam

- Benjamin Britten's Sinfonia da Requiem and Arthur Honegger's Symphonie Liturgique use titles from the traditional Requiem as subtitles of movements.

- Carlo Forlivesi – Requiem, for 8-channel tape[11]

- Hans Werner Henze – Requiem (instrumental)

- Wojciech Kilar "Requiem Father Kolbe"

Modern treatments

In the 20th century the requiem evolved in several new directions. The genre of War Requiem is perhaps the most notable; it consists of compositions dedicated to the memory of people killed in wartime. These often include extra-liturgical poems of a pacifist or non-liturgical nature; for example, the War Requiem of Benjamin Britten juxtaposes the Latin text with the poetry of Wilfred Owen, Krzysztof Penderecki's Polish Requiem includes a traditional Polish hymn within the sequence, and Robert Steadman's Mass in Black intersperses environmental poetry and prophecies of Nostradamus. Holocaust Requiem may be regarded as a specific subset of this type. The World Requiem of John Foulds was written in the aftermath of the First World War and initiated the Royal British Legion's annual festival of remembrance. Recent requiem works by Taiwanese composers Tyzen Hsiao and Fan-Long Ko follow in this tradition, honouring victims of the February 28 Incident and subsequent White Terror.

Lastly, the 20th century saw the development of the secular Requiem, written for public performance without specific religious observance, such as Frederick Delius's Requiem, completed in 1916 and dedicated to "the memory of all young Artists fallen in the war",[12] and Dmitry Kabalevsky's Requiem (Op. 72 – 1962), a setting of a poem written by Robert Rozhdestvensky especially for the composition.[13] Herbert Howells's unaccompanied Requiem uses Psalm 23 ("The Lord is my shepherd"), Psalm 121 ("I will lift up mine eyes"), "Salvator mundi" ("O Saviour of the world," in English), "Requiem aeternam" (two different settings), and "I heard a voice from heaven." Some composers have written purely instrumental works bearing the title of requiem, as famously exemplified by Britten's Sinfonia da Requiem. Hans Werner Henze's Das Floß der Medusa, written in 1968 as a requiem for Che Guevara, is properly speaking an oratorio; Henze's Requiem is instrumental but retains the traditional Latin titles for the movements. Igor Stravinsky's Requiem canticles mixes instrumental movements with segments of the "Introit," "Dies irae," "Pie Jesu," and "Libera me."

See also

References

- ↑ Nott, Charles C. (1902). The Seven Great Hymns of the Mediaeval Church. New York: Edwin S. Gorham. p. 45. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ↑ This translation appears in the English Missal and also The Hymnal 1940 of the Episcopal Church in the USA.

- 1 2 3 Fabrice Fitch: "Requiem (2)", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed January 21, 2007)

- ↑ p. 8, Kinder (2000) Keith William. Westport, Connecticut. The Wind and Wind-Chorus Music of Anton Bruckner Greenwood Press

- ↑ http://schools.aucegypt.edu/fac/Profiles/Pages/johnbaboukis.aspx

- ↑ http://www.requiemsurvey.org/composers.php?id=889

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/mar/25/bob-chilcott-requiem-wells-review

- 1 2 http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2012/Aug12/Hawes_Lazarus_SIGCD282.htm

- ↑ http://www.discogs.com/Ehsan-Saboohi-Phonemes-Requiem/master/912301

- ↑ https://spectropolrecords.bandcamp.com/album/phonemes-requiem

- ↑ ALM Records ALCD-76 Silenziosa Luna

- ↑ Corleonis, Adrian. Requiem, for soprano, baritone, double chorus & orchestra, RT ii/8 All Music Guide, Retrieved 2011-02-20

- ↑ Flaxman, Fred. Controversial Comrade Kabalevsky Compact Discoveries with Fred Flaxman, 2007, Retrieved 2011-02-20;

- Mozart's "Requiem". Spanish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Carlos Kalmar, conductor. Live concert with the completion of its well-known unfinished musical score of the musicologist Robert Levin.

- Fauré's "Requiem". Spanish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Petri Sakari, conductor. Live concert.

- Dvořák's "Requiem". Spanish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Carlos Kalmar, conductor. Live concert.