Japanese phonology

This article deals with the phonology (the sound system) of Standard Japanese.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ɲ) | (ŋ) | N | ||

| Stop | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | (t͡s) (d͡z) | (t͡ɕ) (d͡ʑ) | |||||

| Fricative | (ɸ) | s z | (ɕ) (ʑ) | (ç) | h | ||

| Tap | ɾ | ||||||

| Approximant | (l) | j | w |

- Notes

- Voiceless stops /p t k/ are slightly aspirated: less aspirated than English stops, but more so than Spanish.[1] /p/, a remnant of Old Japanese, now occurs only in Sino-Japanese compounds medially, and in loans from Western languages, Korean, Mandarin, Cantonese, etc. in transcriptions, and in onomatopoeia. /t d n/ are laminal denti-alveolar (that is, the blade of the tongue contacts the back of the upper teeth and the front part of the alveolar ridge) and /s z/ are laminal alveolar. The compressed velar is essentially a non-moraic version of the vowel /u/. It is not equivalent to a typical IPA [w], since it is pronounced with lip compression (IPA: [ɰᵝ] or [w͍]) rather than rounding.

- Consonants inside parentheses are allophones. With the growing tendency of /h s z t d/ being pronounced distinctly (i.e., without the typical Japanese allophonic variation described below) in loanwords, [ɸ ɕ ʑ t͡s d͡z t͡ɕ d͡ʑ] are now tending to occur phonemically in recent loans.[2] /N/ may be considered an allophone of /n m/ in syllable-final position or a distinct phoneme.

See below for more in-detail descriptions of allophonic variation.

- Before /i/, /t d s z/ are alveolo-palatal [t͡ɕ d͡ʑ ɕ ʑ] (often romanized ch j sh j) and before /u/ they are [t͡s d͡z] (often romanized ts dz/z).

- /z/ is pronounced [d͡z] by many speakers when word-initial or following the moraic nasal. It is [d͡ʑ~ʑ] before /i/.[3]

- /h/ is [ç] before /i/ and /j/ (

listen), and [ɸ] before /u/ (often romanized f) (

listen), and [ɸ] before /u/ (often romanized f) ( listen),[4] coarticulated with the labial compression of that vowel.

listen),[4] coarticulated with the labial compression of that vowel. - /N/ is a syllable-final moraic nasal with variable pronunciation depending on what follows.

- Realization of the liquid phoneme /r/ varies greatly depending on environment and dialect. The prototypical and most common pronunciation is the apico-alveolar or postalveolar tap [ɾ].[5][6][4] Initially and after /N/, the tap is typically articulated in such a way that the tip of the tongue is at first momentarily in light contact with the alveolar ridge before being released rapidly by airflow.[7][6] This sound is described variably as a tap, a "variant of [ɾ]", "a kind of weak plosive",[7] and "an affricate with short friction".[4] The apico-alveolar or postalveolar lateral approximant [l] is a common variant in all conditions,[4] particularly utterance-initially[7] and before /i, j/.[5] According to Akamatsu (1997), utterance-initially and intervocalically (that is, except after /N/), the lateral variant is better described as a tap [ɺ] rather than an approximant.[7][8] The retroflex lateral approximant [ɭ] is also found before /i, j/.[5] In Tokyo's Shitamachi dialect, the alveolar trill [r] is a variant marked with vulgarity.[5] Other reported variants include the alveolar approximant [ɹ],[4] the alveolar stop [d], the retroflex flap [ɽ], the lateral fricative [ɮ],[5] and the retroflex stop [ɖ].[9]

Weakening

Non-coronal voiced stops /b, ɡ/ between vowels may be weakened to fricatives, especially in fast and/or casual speech:

/b/ > bilabial fricative [β]: /abareru/ > [aβaɾeɾu] abareru 暴れる 'to behave violently' /ɡ/ > velar fricative [ɣ]: /haɡe/ > [haɣe] hage はげ 'baldness'

However, /ɡ/ is further complicated by its variant realization as a velar nasal [ŋ]. Standard Japanese speakers can be categorized into 3 groups (A, B, C), which will be explained below. If a speaker pronounces a given word consistently with the allophone [ŋ] (i.e. a B-speaker), that speaker will never have [ɣ] as an allophone in that same word. If a speaker varies between [ŋ] and [ɡ] (i.e. an A-speaker) or is generally consistent in using [ɡ] (i.e. a C-speaker), then the velar fricative [ɣ] is always another possible allophone in fast speech.

/ɡ/ may be weakened to nasal [ŋ] when it occurs within words—this includes not only between vowels but also between a vowel and a consonant. There is a fair amount of variation between speakers, however. Vance (1987) suggests that the variation follows social class, while Akamatsu (1997) suggests that the variation follows age and geographic location (p. 130). The generalized situation is as follows.

- At the beginning of words

- all present-day standard Japanese speakers generally use the stop [ɡ] at the beginning of words: /ɡaijuu/ > [ɡaijuu] gaiyū 外遊 'overseas trip' (but not *[ŋaijuu])

- In the middle of simple words (i.e. non-compounds)

- A. a majority of speakers uses either [ŋ] or [ɡ] in free variation: /kaɡu/ > [kaŋu] or [kaɡu] kagu 家具 'furniture'

- B. a minority of speakers consistently uses [ŋ]: /kaɡu/ > [kaŋu] (but not *[kaɡu])

- C. most speakers in western Japan and a smaller minority of speakers in Kantō consistently use [ɡ]: /kaɡu/ > [kaɡu] (but not *[kaŋu])

In the middle of compound words morpheme-initially:

- B-speakers mentioned directly above consistently use [ɡ].

So, for some speakers the following two words are a minimal pair while for others they are homophonous:

- sengo 千五 (せんご) 'one thousand and five' = [seŋɡo] for B-speakers

- sengo 戦後 (せんご) 'postwar' = [seŋŋo] for B-speakers[10]

To summarize using the example of hage はげ 'baldness':

- A-speakers: /haɡe/ > [haŋe] or [haɡe] or [haɣe]

- B-speakers: /haɡe/ > [haŋe]

- C-speakers: /haɡe/ > [haɡe] or [haɣe]

Palatalization and affrication

The palatals /i/ and /j/ palatalize the consonants preceding them:[4]

/m/ > palatalized [mʲ]: /umi/ > [umʲi] umi 海 'sea' /ɡ/ > palatalized [ɡʲ]: /ɡjoːza/ > [ɡʲoːza] gyōza ぎょうざ 'fried dumpling' etc.

For coronal consonants, the palatalization goes further so that alveolo-palatal consonants correspond with dental or alveolar consonants ([ta] 'field' vs. [t͡ɕa] 'tea'):[11]

/n/ > Alveolo-palatal nasal [ɲ̟]: /nihon/ > [ɲihoɴ] nihon 日本 'Japan' /s/ > alveolo-palatal fricative [ɕ]: /sio/ > [ɕi.o] shio 塩 'salt' /z/ > alveolo-palatal [d͡ʑ] or [ʑ]: /zisiN/ > [d͡ʑiɕiɴ] jishin 地震 'earthquake';

/ɡozjuː/ > [ɡod͡ʑuː] ~ [ɡoʑuː] gojū 五十 'fifty'/t/ > alveolo-palatal affricate [t͡ɕ]: /tiziN/ > [t͡ɕid͡ʑiɴ] ~ [t͡ɕiʑiɴ] chijin 知人 'acquaintance'

/i/ and /j/ also palatalize /h/ to a palatal fricative ([ç]): /hito/ > [çito] hito 人 ('person')

Of the allophones of /z/, the affricate [d͡z] is most common, especially at the beginning of utterances and after /N/ (or /n/, depending on the analysis), while fricative [z] may occur between vowels. Both sounds, however, are in free variation.

In the case of the /s/, /z/, and /t/, when followed by /j/, historically, the consonants were palatalized with /j/ merging into a single pronunciation. In modern Japanese, these are arguably separate phonemes, at least for the portion of the population that pronounces them distinctly in English borrowings.

/sj/ > [ɕ] (romanized as sh): /sjaboN/ > [ɕaboɴ] shabon シャボン 'soap' /zj/ > [d͡ʑ ~ ʑ] (romanized as j): /zjaɡaimo/ > [d͡ʑaɡaimo] jagaimo じゃがいも 'potato' /tj/ > [t͡ɕ] (romanized as ch): /tja/ > [t͡ɕa] cha 茶 'tea' /hj/ > [ç] (romanized as hy): /hjaku/ > [çaku] hyaku 百 'hundred'

The vowel /u/ also affects consonants that it follows:[12]

/h/ > bilabial fricative [ɸ]: /huta/ > [ɸuta] futa ふた 'lid' /t/ > dental affricate [t͡s]: /tuɡi/ > [t͡suɡi] tsugi 次 'next'

Although [ɸ] and [t͡s] occur before other vowels in loanwords (e.g. [ɸaito] 'fight'; [ɸjuː(d)ʑoɴ] 'fusion'; [t͡saitoɡaisuto] 'Zeitgeist'; [eɾit͡siɴ] 'Yeltsin'), [ɸ] and [h] are distinguished before vowels except [u] (e.g. English fork vs. hawk > [ɸoːku] fōku vs. [hoːku] hōku). *[hu] is still not distinguished from [ɸu] (e.g. English hood vs. food > [ɸuːdo] fūdo).[13] Similarly, *[si] and *[zi] do not occur even in loanwords so that English cinema becomes [ɕinema] shinema.[14]

Moraic nasal

Some analyses of Japanese treat the moraic nasal as an archiphoneme /N/;[15] however, other less abstract approaches take its uvular pronunciation as basic or treat it as coronal /n/ appearing in the syllable coda. Even when the nasal coda is proposed as /n/, it is distinct from /n/ as a syllable onset.[4] In any case, it undergoes a variety of assimilatory processes. Within words, it is variously:[16]

- uvular [ɴ] at the end of utterances and in isolation. Dorsal occlusion may not always be complete.[17]

- bilabial [m] before [p, b, m]; this pronunciation is also sometimes found at the end of utterances and in isolation. Singers are taught to pronounce all final and prevocalic instances of this sound as [m], which reflects its historical derivation.

- laminal [n] before coronals /d, t, n/; never found utterance-finally. It is alveolo-palatal [ɲ̟] before alveolo-palatal affricates [t͡ɕ, d͡ʑ].[17] Apical [n̺] is found before liquid /r/.[18]

- velar [ŋ] before [k, ɡ]. Before palatalized consonants, it is also palatalized, as in [ɡẽŋʲkʲi].[17]

- some sort of nasalized vowel before vowels, approximants ([j, w]), liquid /r/, and fricatives ([ɸ, s, z, ɕ, ç, h]). Depending on context and speaker, the vowel's quality may closely match that of the preceding vowel or be more constricted in articulation. It is thus broadly transcribed with [ɰ̃], an ad hoc semivocalic notation undefined for the exact place of articulation.[17] It is also found utterance-finally.[4]

Some speakers produce [n] before /z/, pronouncing them as [nd͡z], while others produce a nasalized vowel before /z/.[19]

These assimilations occur beyond word boundaries.

Gemination

While Japanese features consonant gemination, there are some limitations in what can be geminated. Most saliently, voiced geminates are prohibited in native Japanese words.[20] This can be seen with suffixation that would otherwise feature voiced geminates. For example, Japanese has a suffix, |ri| that contains what Kawahara (2006) calls a "floating mora" that triggers gemination in certain cases (e.g. |tapu| +|ri| > [tappuɾi] 'a lot of'). When this would otherwise lead to a geminated voiced obstruent, a moraic nasal appears instead as a sort of "partial gemination" (e.g. |zabu| + |ri| > [zambuɾi] 'splashing').[21][22]

However, voiced geminates do appear in loanwords. These loanwords can even come from languages, such as English, that do not feature gemination in the first place. For example, when an English word features a coda consonant followed by a lax vowel, it can be borrowed into Japanese featuring a geminate; gemination may also appear as a result of borrowing via written materials, where a word spelled with doubled letters leads to a geminated pronunciation.[23] Because these loanwords can feature voiced geminates, Japanese now exhibits a voice distinction with geminates where it formerly did not:[24]

- suraggā スラッガー ('slugger') vs. surakkā ('slacker')

- kiddo キッド ('kid') vs. kitto ('kit')

This distinction is not very rigorous. For example, when voiced obstruent geminates appear with another voiced obstruent they can undergo optional devoicing (e.g. doreddo ~ doretto 'dreadlocks'). Kawahara (2006) attributes this to a less reliable distinction between voiced and voiceless geminates compared to the same distinction in non-geminated consonants, noting that speakers may have difficulty distinguishing them due to the partial devoicing of voiced geminates and their resistance to the weakening process mentioned above, both of which can make them sound like voiceless geminates.[25]

There is some dispute about how gemination fits with Japanese phonotactics. One analysis, particularly popular among Japanese scholars, posits a special "mora phoneme" (モーラ 音素 Mōra onso) /Q/, which corresponds to the sokuon ⟨っ⟩.[26] However, not all scholars agree that the use of this "moraic obstruent" is the best analysis. In those approaches that incorporate the moraic obstruent, it is said to completely assimilate to the following obstruent, resulting in a geminate (that is, double) consonant. The assimilated /Q/ remains unreleased and thus the geminates are phonetically long consonants. /Q/ does not occur before vowels or nasal consonants. This can be seen as an archiphoneme in that it has no underlying place or manner of articulation, and instead manifests as several phonetic realizations depending on context, for example:

[p̚] before [p]: /niQ.poN/ > [nʲip̚.poɴ] nippon 日本 'Japan' [s] before [s]: /kaQ.seN/ > [kas.seɴ] kassen 合戦 'battle' [t̚] before [t͡ɕ]: /saQ.ti/ > [sat̚.t͡ɕi] satchi 察知 'inference' etc.

Another analysis of Japanese dispenses with /Q/ and other moraic phonemes entirely. In such an approach, the words above are phonemicized as shown below:

[p̚] before [p]: /nip.pon/ > [nʲip̚.poɴ] nippon 日本 'Japan' [s] before [s]: /kas.sen/ > [kas.seɴ] kassen 合戦 'battle' [t̚] before [t͡ɕ]: /sat.ti/ > [sat̚.t͡ɕi] satchi 察知 'inference' etc.

Gemination can of course also be transcribed with a length mark (e.g. [nʲipːoɴ]), but this notation obscures mora boundaries.

Gemination does not occur only in yamato kotoba, kango, or gairaigo exclusively, but also in combinations of those three types of categories. For example, 一ターン, a combination of the kango 一 (ichi "one") and the gairaigo ターン (tān "turn"), is pronounced ittān.

/d, z/ neutralization

The contrast between /d/ and /z/ is neutralized before /u/ and /i/: [zu, d͡ʑi]. By convention, it is often assumed to be /z/, though some analyze it as /d/, the voiced counterpart to [t͡s]. The writing system preserves morphological distinctions, though spelling reform has eliminated historical distinctions except in cases where a mora is repeated once voiceless and once voiced, or where rendaku occurs in a compound word: つづく[続く] /tuduku/, いちづける[位置付ける] /itidukeru/ from |iti+tukeru|,

Sandhi

Various forms of sandhi exist; the Japanese term for sandhi generally is ren'on (連音), while the Japanese form is referred to as renjō (連声). Most commonly, a terminal /n/ on one morpheme results in an /n/ (or /m/) being added to the start of the next morpheme, as in tennō (天皇, emperor), てん + おう > てんのう (ten + ō = tennō). In some cases, such as this example, the sound change is used in writing as well, and is considered the usual pronunciation, though in other cases, such as abbreviating ...-no-uchi (〜の家, ...'s house) to 〜んち (-nchi) this is only done in speech, and considered informal. See 連声 (in Japanese) for further examples.

Vowels

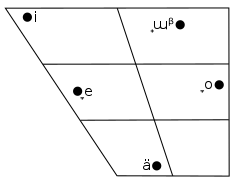

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

- /u/ is a close near-back vowel with lip compression (IPA: [ɯ̟ᵝ] or [u͍˖]) (

listen). That is, unlike [u] or [ɯ], it is pronounced with the side portions of the lips in contact but with no salient protrusion. After [s, z, n, j], it is centralized (IPA: [ɨᵝ] or [ʉ͍]).[27]

listen). That is, unlike [u] or [ɯ], it is pronounced with the side portions of the lips in contact but with no salient protrusion. After [s, z, n, j], it is centralized (IPA: [ɨᵝ] or [ʉ͍]).[27] - /e, o/ are mid [e̞, o̞].[28]

- /a/ is central [ä].[28]

All of the Japanese vowels are pronounced as monophthongs. Except for /u/, the short vowels are similar to their Spanish counterparts.

Vowels have a phonemic length contrast (i.e. short vs. long). Compare contrasting pairs of words like ojisan /ozisaN/ 'uncle' vs. ojiisan /oziisaN/ 'grandfather', or tsuki /tuki/ 'moon' vs. tsūki /tuuki/ 'airflow'.

In most phonological analyses, all syllables with a short vowel as their rime are treated as occurring within the timeframe of one mora, or in other terms, one beat. According to traditional conventions, long vowels are described as a sequence of two identical vowels. For example, ojiisan will be rendered as /oziisaN/, not /oziːsaN/. Analysing long vowels in this manner is in accord with the traditions of Japanese linguistics and poetry, wherein long vowels are always considered separate moras.

Within words and phrases, Japanese allows long sequences of phonetic vowels without intervening consonants, pronounced with hiatus, although the pitch accent and slight rhythm breaks help track the timing when the vowels are identical. Sequences of two vowels within a single word are extremely common, occurring at the end of many i-type adjectives, for example, and having three or more vowels in sequence within a word also occurs, as in aoi 'blue/green'. In phrases, sequences with multiple o sounds are most common, due to the direct object particle を 'wo' (which comes after a word) being realized as o and the honorific prefix お〜 'o', which can occur in sequence, and may follow a word itself terminating in an o sound; these may be dropped in rapid speech. A fairly common construction exhibiting these is 「〜をお送りします」 ... (w)o o-okuri-shimasu 'humbly send ...'. More extreme examples follow:

/hoo.oo.o.ou/ [hoː.oː.o.ou] hōō o ou (鳳凰を追う) 'to chase a phoenix (Fenghuang)' /too.oo.o.oo.u/ [toː.oː.o.oː.u] tōō o ōu (東欧を覆う) 'to cover Eastern Europe'

Devoicing

In many dialects, the close vowels /i/ and /u/ become voiceless when placed between two voiceless consonants or, unless accented, between a voiceless consonant and a pausa.[29]

/kutu/ > [ku̥t͡su] kutsu 靴 'shoe' /atu/ > [at͡su̥] atsu 圧 'pressure' /hikaN/ > [çi̥kaɴ] hikan 悲観 'pessimism'

Generally, devoicing does not occur in a consecutive manner:[30]

/kisitu/ > [kʲi̥ɕit͡su] kishitsu 気質 'temperament' /kusikumo/ > [kuɕi̥kumo] kushikumo 奇しくも 'strangely'

This devoicing is not restricted to only fast speech, though consecutive voicing may occur in fast speech.[31]

To a lesser extent, /o, a/ may be devoiced with the further requirement that there be two or more adjacent moras containing the same phoneme:[29]

/kokoro/ > [ko̥koɾo] kokoro 心 'heart' /haka/ > [hḁka] haka 墓 'grave'

The common sentence-ending copula desu and polite suffix masu are typically pronounced [desu̥] and [masu̥].[32]

Japanese speakers are usually not even aware of the difference of the voiced and devoiced pair. On the other hand, gender roles play a part in prolonging the terminal vowel: it is regarded as effeminate to prolong, particularly the terminal /u/ as in arimasu. Some nonstandard varieties of Japanese can be recognized by their hyper-devoicing, while in some Western dialects and some registers of formal speech, every vowel is voiced.

Nasalization

Japanese vowels are slightly nasalized when adjacent to nasals /m, n/. Before the moraic nasal /N/, vowels are heavily nasalized:

/seesaN/ > [seːsãɴ] seisan 生産 'production'

Glottal stop insertion

At the beginning and end of utterances, Japanese vowels may be preceded and followed by a glottal stop [ʔ], respectively. This is demonstrated below with the following words (as pronounced in isolation):

/eN/ > [eɴ] ~ [ʔeɴ]: en 円 'yen' /kisi/ > [kiɕiʔ]: kishi 岸 'shore' /u/ > [uʔ ~ ʔuʔ]: u 鵜 'cormorant'

When an utterance-final word is uttered with emphasis, this glottal stop is plainly audible, and is often indicated in the writing system with a small letter tsu ⟨っ⟩ called a sokuon. This is also found in interjections like あっ and えっ. These words are likely to be romanized as ⟨a'⟩ and ⟨e'⟩, or rarely as ⟨at⟩ and ⟨et⟩

Phonotactics

| /-a/ | /-i/ | /-u/ | /-e/ | /-o/ | /-ja/ | /-ju/ | /-jo/ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /∅-/ | /a/ | /i/ | /u/ | /e/ | /o/ | ||||

| /k-/ | /ka/ | /ki/ [kʲi] | /ku/ | /ke/ | /ko/ | /kja/ [kʲa] | /kju/ [kʲu] | /kjo/ [kʲo] | |

| /ɡ-/ | /ɡa/ | /ɡi/ [ɡʲi] | /ɡu/ | /ɡe/ | /ɡo/ | /ɡja/ [ɡʲa] | /ɡju/ [ɡʲu] | /ɡjo/ [ɡʲo] | |

| /s-/ | /sa/ | /si/ [ɕi] | /su/ | /se/ | /so/ | /sja/ [ɕa] | /sju/ [ɕu] | /sjo/ [ɕo] | |

| /z-/ | /za/ | /zi/ [(d)ʑi] | /zu/ [(d)zu] | /ze/ | /zo/ | /zja/ [(d)ʑa] | /zju/ [(d)ʑu] | /zjo/ [(d)ʑo] | |

| /t-/ | /ta/ | /ti/ [t͡ɕi] | /tu/ [t͡su] | /te/ | /to/ | /tja/ [t͡ɕa] | /tju/ [t͡ɕu] | /tjo/ [t͡ɕo] | |

| /d-/ | /da/ | /di/ [(d)ʑi] | /du/ [(d)zu] | /de/ | /do/ | /dja/ [(d)ʑa] | /dju/ [(d)ʑu] | /djo/ [(d)ʑo] | |

| /n-/ | /na/ | /ni/ [ɲi] | /nu/ | /ne/ | /no/ | /nja/ [ɲa] | /nju/ [ɲu] | /njo/ [ɲo] | |

| /h-/ | /ha/ | /hi/ [çi] | /hu/ [ɸu] | /he/ | /ho/ | /hja/ [ça] | /hju/ [çu] | /hjo/ [ço] | |

| /p-/ | /pa/ | /pi/ [pʲi] | /pu/ | /pe/ | /po/ | /pja/ [pʲa] | /pju/ [pʲu] | /pjo/ [pʲo] | |

| /b-/ | /ba/ | /bi/ [bʲi] | /bu/ | /be/ | /bo/ | /bja/ [bʲa] | /bju/ [bʲu] | /bjo/ [bʲo] | |

| /m-/ | /ma/ | /mi/ [mʲi] | /mu/ | /me/ | /mo/ | /mja/ [mʲa] | /mju/ [mʲu] | /mjo/ [mʲo] | |

| /j-/ | /ja/ | /ju/ | /jo/ | ||||||

| /r-/ | /ra/ [ɾa] | /ri/ [ɾʲi] | /ru/ [ɾu] | /re/ [ɾe] | /ro/ [ɾo] | /rja/ [ɾʲa] | /rju/ [ɾʲu] | /rjo/ [ɾʲo] | |

| /w-/ | /wa/ | ||||||||

| Marginal combinations mostly found in Western loans | |||||||||

| [ɕ-] | [ɕe] | ||||||||

| [(d)ʑ-] | [(d)ʑe] | ||||||||

| [t-] | [tʲi] | [tu] | [tʲu] | ||||||

| [t͡ɕ-] | [t͡ɕe] | ||||||||

| [t͡s-] | [t͡sa] | [t͡sʲi] | [t͡se] | [t͡so] | |||||

| [d-] | [dʲi] | [du] | [dʲu] | ||||||

| [ɸ-] | [ɸa] | [ɸʲi] | [ɸu] | [ɸe] | [ɸo] | [ɸʲu] | |||

| [w-] | [wi] | [we] | [wo] | ||||||

| Special moras | |||||||||

| /V-/ | /N/ [ɴ, m, n, ɲ, ŋ, ɰ̃] | ||||||||

| /C-/ | /Q/ [ː] | ||||||||

| /V-/ | /R/ [ː] | ||||||||

Japanese words have traditionally been analysed as composed of moras; a distinct concept from that of syllables.[33] Each mora occupies one rhythmic unit, i.e. it is perceived to have the same time value.[34] A mora may be "regular" consisting of just a vowel (V) or a consonant and a vowel (CV), or may be one of two "special" moras, /N/ and /Q/. A glide /j/ may precede the vowel in "regular" moras (CjV). Some analyses posit a third "special" mora, /R/, the second part of a long vowel.[35] In this table, the period represents a mora break, rather than the conventional syllable break.

Mora type Example Japanese Moras per word V /o/ o 尾 'tail' 1-mora word jV /jo/ yo 世 'world' 1-mora word CV /ko/ ko 子 'child' 1-mora word CjV /kjo/1 kyo 巨 'hugeness' 1-mora word R /R/ in /kjo.R/ or /kjo.o/ kyō 今日 'today' 2-mora word N /N/ in /ko.N/ kon 紺 'deep blue' 2-mora word Q /Q/ in /ko.Q.ko/ or /ko.k̚.ko/ kokko 国庫 'national treasury' 3-mora word - ^1 Traditionally, moras were divided into plain and palatal sets, the latter of which entail palatalization of the consonant element.[36]

Consonantal moras are restricted from occurring word initially, though utterances starting with [n] are possible. Vowels may be long, and consonants may be geminate (doubled). In the analysis with archiphonemes, geminate consonants are the realization of the sequences /Nn/, /Nm/ and sequences of /Q/ followed by a voiceless obstruent, though some words are written with geminate voiced obstruents. In the analysis without archiphonemes, geminate clusters are simply two identical consonants, one after the other.

In English, stressed syllables in a word are pronounced louder, longer, and with higher pitch, while unstressed syllables are relatively shorter in duration. In Japanese, all moras are pronounced with equal length and loudness. Japanese is therefore said to be a mora-timed language.

Accent

Standard Japanese has a distinctive pitch accent system: a word can have one of its moras bearing an accent or not. An accented mora is pronounced with a relatively high tone and is followed by a drop in pitch. The various Japanese dialects have different accent patterns, and some exhibit more complex tonic systems.

Sound change

As an agglutinative language, Japanese has generally very regular pronunciation, with much simpler morphophonology than a fusional language would. Nevertheless, there are a number of prominent sound change phenomena, primarily in morpheme combination and in conjugation of verbs and adjectives. Phonemic changes are generally reflected in the spelling, while those that are not either indicate informal or dialectal speech which further simplify pronunciation.

Sandhi

Rendaku

In Japanese, sandhi is prominently exhibited in rendaku – consonant mutation of the initial consonant of a morpheme from unvoiced to voiced in some contexts when it occurs in the middle of a word. This phonetic difference is reflected in the spelling via the addition of dakuten, as in ka, ga (か/が). In cases where this combines with the yotsugana mergers, notably ji, dzi (じ/ぢ) and zu, dzu (ず/づ) in standard Japanese, the resulting spelling is morphophonemic rather than purely phonemic.

Gemination

The other common sandhi in Japanese is conversion of つ or く (tsu, ku), and ち or き (chi, ki), and rarely ふ or ひ (fu, hi) as a trailing consonant to a geminate consonant when not word-final – orthographically, the sokuon っ, as this occurs particularly in the context of つ. So that

- 一 (itsu) + 緒 (sho) = 一緒 (issho)

- 学 (gaku) + 校 (kō) = 学校 (gakkō)

Many historically long vowels, especially "ō" in present Japanese, derive from a former fu so that

- 法 (hafu > hō) + 被 (hi) = 法被 (happi), instead of hōhi.

- 法 (bofu > bō) + 師 (shi) = 法師 (botchi), sometimes bōshi.

- 合 (kafu > gō) + 戦 (sen) = 合戦 (kassen), instead of gōsen

- 入 (nifu > nyū) + 声 (shō) = 入声 (nisshō), instead of nyūshō

- 十 (jifu > jū) + 戒 (kai) = 十戒 (jikkai) instead of jūkai

Most words exhibiting this change are Sino-Japanese words deriving from Middle Chinese morphemes ending in /t̚/, /k̚/ or /p̚/, which were borrowed on their own into Japanese with a prop vowel after them (e.g. 日 MC */nit̚/ > Japanese /niti/ [ɲit͡ɕi]) but in compounds as assimilated to the following consonant (e.g. 日本 MC */nit̚.pu̯ən/ > Japanese /niQ.poN/ [ɲip̚.poɴ]).

The sequence /Np/ (as in 三平 (sanpei), 寒風 (kanpū), etc.) can be considered "soft" gemination, and like /Qp/, it has helped preserve the Old Japanese phoneme /p/ all the way into modern Japanese.

Renjō

Sandhi also occurs much less often in renjō (連声), where, most commonly, a terminal /N/ or /Q/ on one morpheme results in /n/ (or /m/ when derived from historical m) or /t̚/ respectively being added to the start of a following morpheme beginning with a vowel or semivowel, as in ten + ō → tennō (天皇: てん + おう → てんのう). Examples:

- First syllable ending with /N/

- 銀杏 (ginnan): ぎん (gin) + あん (an) → ぎんなん (ginnan)

- 観音 (kannon): くゎん (kwan) + おむ (om) → くゎんのむ (kwannom) → かんのん (kannon)

- 天皇 (tennō): てん (ten) + わう (wau) → てんなう (tennau) → てんのう (tennō)

- First syllable ending with /N/ from original /m/

- 三位 (sanmi): さむ (sam) + ゐ (wi) → さむみ (sammi) → さんみ (sanmi)

- 陰陽 (onmyō): おむ (om) + やう (yau) → おむみゃう (ommyau) → おんみょう (onmyō)

- First syllable ending with /Q/

- 雪隠 (setchin): せつ (setsu) + いん (in) → せっちん (setchin)

- 屈惑 (kuttaku): くつ (kutsu) + わく (waku) → くったく (kuttaku)

Onbin

Another prominent feature is onbin (音便, euphonic sound change), particularly historical sound changes.

In cases where this has occurred within a morpheme, the morpheme itself is still distinct but with a different sound, as in hōki (箒 (ほうき), broom), which underwent two sound changes from earlier hahaki (ははき) → hauki (はうき) (onbin) → houki (ほうき) (historical vowel change) → hōki (ほうき) (long vowel, sound change not reflected in kana spelling).

However, certain forms are still recognizable as irregular morphology, particularly forms that occur in basic verb conjugation, as well as some compound words.

Verb conjugation

Polite adjective forms

The polite adjective forms (used before the polite copula gozaru (ござる, be) and verb zonjiru (存じる, think, know)) exhibit a one-step or two-step sound change. Firstly, these use the continuative form, -ku (-く), which exhibits onbin, dropping the k as -ku (-く) → -u (-う). Secondly, the vowel may combine with the preceding vowel, according to historical sound changes; if the resulting new sound is palatalized, meaning yu, yo (ゆ、よ), this combines with the preceding consonant, yielding a palatalized syllable.

This is most prominent in certain everyday terms that derive from an i-adjective ending in -ai changing to -ō (-ou), which is because these terms are abbreviations of polite phrases ending in gozaimasu, sometimes with a polite o- prefix. The terms are also used in their full form, with notable examples being:

- arigatō (有難う、ありがとう, Thank you), from arigatai (有難い、ありがたい, (I am) grateful).

- ohayō (お早う、おはよう, Good morning), from hayai (早い、はやい, (It is) early).

- omedetō (お目出度う、おめでとう, Congratulations), from medetai (目出度い、めでたい, (It is) auspicious).

Other transforms of this type are found in polite speech, such as oishiku (美味しく) → oishū (美味しゅう) and ōkiku (大きく) → ōkyū (大きゅう).

-hito

The morpheme hito (人 (ひと), person) (with rendaku -bito (〜びと)) has changed to uto (うと) or udo (うど), respectively, in a number of compounds. This in turn often combined with a historical vowel change, resulting in a pronunciation rather different from that of the components, as in nakōdo (仲人 (なこうど), matchmaker) (see below). These include:

- otōto (弟 (おとうと), younger brother), from otohito (弟人 (おとひと)) → otouto (おとうと) → otōto.

- imōto (妹 (いもうと), younger sister), from imohito (妹人 (いもひと)) → imouto (いもうと) → imōto.

- shirōto (素人 (しろうと), novice), from shirohito (白人 (しろひと)) → shirouto (しろうと) → shirōto.

- kurōto (玄人 (くろうと), veteran), from kurohito (黒人 (くろひと)) → kurouto (くろうと) → kurōto.

- nakōdo (仲人 (なこうど), matchmaker), from nakabito (仲人 (なかびと)) → nakaudo (なかうど) → nakoudo (なこうど) → nakōdo.

- karyūdo (狩人 (かりゅうど), hunter), from karibito (狩人 (かりびと)) → kariudo (かりうど) → karyuudo (かりゅうど) → karyūdo.

- shūto (舅 (しゅうと), stepfather), from shihito (舅人 (しひと)) → shiuto (しうと) → shuuto (しゅうと) → shūto.

Fusion

In some cases morphemes have effectively fused and will not be recognizable as being composed of two separate morphemes.

Notes

- ↑ Riney et al. (2007).

- ↑ Labrune (2012), p. 59.

- ↑ Akamatsu (2000), pp. 81 fn 5, 135.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Okada (1991), p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Labrune (2012), p. 92.

- 1 2 Vance (2008), p. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 Akamatsu (1997), p. 106.

- ↑ Akamatsu (1997) employs a different symbol, [l̆], for the lateral tap.

- ↑ Arai, Warner & Greenberg (2007), p. 48.

- ↑ Japanese academics represent [ɡo] as ご and [ŋo] as こ゜.

- ↑ Itō & Mester (1995), p. 827.

- ↑ Itō & Mester (1995), p. 825.

- ↑ Itō & Mester (1995), p. 826.

- ↑ Itō & Mester (1995), p. 828.

- ↑ Labrune (2012), pp. 132–3.

- ↑ Labrune (2012), pp. 133–4.

- 1 2 3 4 Vance (2008), p. 96.

- ↑ Vance (2008), p. 97.

- ↑ Akamatsu (1997).

- ↑ Labrune (2012), p. 104.

- ↑ Kawahara (2006), p. 550.

- ↑ Labrune (2012:104–5) points out that the prefix |bu| has the same effect.

- ↑ Kawahara (2006:537–8), citing Katayama (1998)

- ↑ Kawahara (2006), p. 538.

- ↑ Kawahara (2006), pp. 559, 561, 565.

- ↑ Labrune (2012), p. 135.

- ↑ Vance (2008), pp. 54–6.

- 1 2 Okada (1991), p. 94.

- 1 2 Labrune (2012), pp. 34–5.

- ↑ Tsuchida (2001), p. 225.

- ↑ Tsuchida (2001), fn 3.

- ↑ Seward (1992), p. 9.

- ↑ Moras are represented orthographically in katakana and hiragana – each mora, with the exception of CjV clusters, being one kana – and are referred to in Japanese as 'on' or 'onji'.

- ↑ Labrune (2012), p. 143.

- ↑ Labrune (2012), pp. 143–4.

- ↑ Itō & Mester (1995:827). In such a classification scheme, the plain counterparts of moras with a palatal glide are onsetless moras.

References

- Akamatsu, Tsutomu (1997), Japanese Phonetics: Theory and Practice, München: Lincom Europa, ISBN 3-89586-095-6

- Akamatsu, Tsutomu (2000), Japanese Phonology: A Functional Approach, München: Lincom Europa, ISBN 3-89586-544-3

- Arai, Takayuki; Warner, Natasha; Greenberg, Steven (2007), "Analysis of spontaneous Japanese in a multi-language telephone-speech corpus", Acoustical Science and Technology, 28 (1): 46–48, doi:10.1250/ast.28.46

- Itō, Junko; Mester, R. Armin (1995), "Japanese phonology", in Goldsmith, John A, The Handbook of Phonological Theory, Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics, Blackwell Publishers, pp. 817–838

- Kawahara, Shigeto (2006), "A Faithfulness ranking projected from a perceptibility scale: The case of [+ Voice] in Japanese", Language, 82 (3): 536–574, doi:10.1353/lan.2006.0146

- Labrune, Laurence (2012), The Phonology of Japanese, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-954583-4

- Okada, Hideo (1991), "Japanese", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 21 (2): 94–96, doi:10.1017/S002510030000445X

- Riney, Timothy James; Takagi, Naoyuki; Ota, Kaori; Uchida, Yoko (2007), "The intermediate degree of VOT in Japanese initial voiceless stops", Journal of Phonetics, 35 (3): 439–443, doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2006.01.002

- Seward, Jack (1992), Easy Japanese, McGraw-Hill Professional, ISBN 978-0-8442-8495-8

- Tsuchida, Ayako (2001), "Japanese vowel devoicing", Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 10 (3): 225–245, doi:10.1023/A:1011221225072

- Vance, Timothy J. (1987), An Introduction to Japanese Phonology, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-88706-360-8

- Vance, Timothy J. (2008), The Sounds of Japanese, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-5216-1754-3

Further reading

- Bloch, Bernard, "Studies in colloquial Japanese IV: Phonemics", Language, 26 (1): 86–125, JSTOR 410409, OCLC 486707218, doi:10.2307/410409

- Haraguchi, Shosuke (1977), The tone pattern of Japanese: An autosegmental theory of tonology, Tokyo, Japan: Kaitakusha, ISBN 0-87040-371-0

- Haraguchi, Shosuke (1999), "Chap. 1: Accent", in Tsujimura, Natsuko, The Handbook of Japanese Linguistics, Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 1–30, ISBN 0-631-20504-7

- (dissertation) Katayama, Motoko (1998), Loanword phonology in Japanese and optimality theory, Santa Cruz: University of California, Santa Cruz

- Kubozono, Haruo (1999), "Chap. 2: Mora and syllable", in Tsujimura, Natsuko, The Handbook of Japanese Linguistics, Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 31–61, ISBN 0-631-20504-7

- Ladefoged, Peter (2001), A Course in Phonetics (4th ed.), Boston: Heinle & Heinle, Thomson Learning, ISBN 0-15-507319-2

- Martin, Samuel E. (1975), A reference grammar of Japanese, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-01813-4

- McCawley, James D. (1968), The Phonological Component of a Grammar of Japanese, The Hague: Mouton

- Pierrehumbert, Janet; Beckman, Mary (1988), Japanese Tone Structure, Linguistic Inquiry monographs (No. 15), Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-16109-5

- Sawashima, M.; Miyazaki, S. (1973), "Glottal opening for Japanese voiceless consonants", Annual Bulletin, Research Institute of Logopedics and Phoniatrics, University of Tokyo, 7: 1–10, OCLC 633878218

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990), "Japanese", in Comrie, Bernard, The major languages of east and south-east Asia, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-04739-0

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990), The Languages of Japan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-36070-6