President of Germany (1919–1945)

| President of Germany | |

|---|---|

|

Standard of the President (1926–1933) | |

| Style | His Excellency |

| Residence | Presidential Palace |

| Seat | Berlin, Germany |

| Appointer | Direct election under a two-round system |

| Precursor | German Emperor |

| Formation | 11 February 1919 |

| First holder | Friedrich Ebert |

| Final holder | Paul von Hindenburg |

| Abolished |

|

| Succession |

|

The Reichspräsident was the German head of state under the Weimar constitution, which was officially in force from 1919 to 1945. In English he was usually simply referred to as the President of Germany. The German title Reichspräsident literally means President of the Reich, the term Reich referring to the federal nation state established in 1871.

The Weimar constitution created a semi-presidential system in which power was divided between the president, a cabinet and a parliament.[1][2][3] The Reichspräsident was directly elected under universal adult suffrage for a seven-year term. It was intended that the president would rule in conjunction with the Reichstag (legislature) and that his emergency powers would be exercised only in extraordinary circumstances, but the political instability of the Weimar period, and a paralysing factionalism in the legislature, meant that the president came to occupy a position of considerable power (not unlike that of the German Emperor he replaced), capable of legislating by decree and appointing and dismissing governments at will.

In 1934, after the death of President Hindenburg, Adolf Hitler, already Chancellor, assumed the office of Presidency,[4] but did not usually use the title of President – ostensibly out of respect for Hindenburg – and preferred to rule as Führer und Reichskanzler ("Leader and Reich Chancellor"), highlighting the positions he already held in party and government. In his last will in April 1945, Hitler named Joseph Goebbels his successor as Chancellor but named Karl Dönitz as Reichspräsident, thus reviving the individual office for a short while until the German surrender.

The German Basic Law of 1949 established the office of Federal President (Bundespräsident), which is, however, a chiefly ceremonial post largely devoid of political power.

List of officeholders

- Political Party

| No. | Portrait | Name (Born-Died) |

Elected | Took office | Left office | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Friedrich Ebert (1871–1925) |

1919 | 11 February 1919 | 28 February 1925 (died in office) |

SPD |

| – |  |

Hans Luther (acting)[A] (1879–1962) |

– | 28 February 1925 | 12 March 1925 | Non-partisan |

| – |  |

Walter Simons (acting)[B] (1861–1937) |

– | 12 March 1925 | 12 May 1925 | Non-partisan |

| 2 |  |

Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934) |

1925 1932 |

12 May 1925 | 2 August 1934 (died in office) |

Non-partisan |

A Hans Luther, Chancellor of Germany, was acting head of state from 28 February to 12 March 1925.

B Walter Simons, President of the Supreme Court, was acting head of state from 12 March to 12 May 1925.

Upon Generalfeldmarschall von Hindenburg's death, Adolf Hitler merged the offices of Chancellor and head of state in his person. He styled himself Führer und Reichskanzler ("Leader and Chancellor"), but did not use the title of Reichspräsident. Upon his suicide on 30 April 1945, Hitler nominated Großadmiral Karl Dönitz to be President. Dönitz was arrested on 23 May 1945 and the office was dissolved.

Election

Under the Weimar constitution, the President was directly elected by universal adult suffrage for a term of seven years; reelection was not limited.

The law provided that the presidency was open to all German citizens who had reached 35 years of age. The direct election of the president occurred under a form of the two round system. If no candidate received the support of an absolute majority of votes cast (i.e. more than half) in a first round of voting, a second vote was held at a later date. In this round the candidate who received the support of a plurality of voters was deemed elected. A group could also nominate a substitute candidate in the second round, in place of the candidate it had supported in the first.

The President could not be a member of the Reichstag (parliament) at the same time. The constitution required that on taking office the president swore the following oath (the inclusion of additional religious language was permitted):

- I swear to devote my energy to the welfare of the German people, to increase its prosperity, to prevent damage, to hold up the Reich constitution and its laws, to consciously honour my duties and to exercise justice to every individual.

Only two regular presidential elections under the provisions of the Weimar Constitution actually occurred, in 1925 and 1932:

The first office-holder, the Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert was elected by the National Assembly on 11 February 1919 on a provisional basis.

Ebert intended to stand in presidential elections in 1922 when the outcry about assassination of Walther Rathenau seemed to generate a pro-republican atmosphere. However, National Liberal politician Gustav Stresemann persuaded the other centrist parties that the situation was still too turbulent to hold elections. Hence, the Reichstag extended Ebert's term to June 30, 1925, a move that contravened the constitution's text but was passed by two-thirds of the Reichstag, the majority needed for changes or deviations from the constitution. Ebert died in office in February 1925.

The first presidential election was held in 1925. After the first ballot had not resulted in a clear winner, a second ballot was held, in which Paul von Hindenburg, a war hero nominated by the right-wing parties after their original candidate had dropped out after the first ballot, managed to win a majority. Hindenburg served a full term and was reelected in 1932, this time nominated by the pro-republican parties who thought only he could prevent the election of Adolf Hitler to the office. Hindenburg died in office in August 1934, a little over two years after his reelection, having since appointed Hitler as Chancellor. Hitler then assumed the powers of head of state, but did not use the title of President until his own death, when he named Karl Dönitz his successor as President in his Final Political Will and Testament.

Duties and functions

- Appointment of the Government: The Reichskanzler ("Chancellor") and his cabinet were appointed and dismissed by the president. No vote of confirmation was required in the Reichstag before the members of the cabinet could assume office, but any member of the cabinet was obliged to resign if the body passed a vote of no confidence in him. The president could appoint and dismiss the chancellor at will, but all other cabinet members could, save in the event of a no confidence motion, only be appointed or dismissed at the chancellor's request.

- Dissolution of the Reichstag: The president had the right to dissolve the Reichstag at any time, in which case a general election had to occur within sixty days. Theoretically, he was not permitted to do so more than once for the same "reason", but this limitation had little significance in practice.

- Promulgation of the law: The president was responsible for signing bills into law. The president was constitutionally obliged to sign every law passed in accordance with the correct procedure but could insist that a bill first be submitted to the electorate in a referendum. Such a referendum could, however, only override the decision of the Reichstag if a majority of eligible voters participated.

- Foreign relations: Under the constitution, the president was entitled to represent the nation in its foreign affairs, to accredit and receive ambassadors and to conclude treaties in the name of the state. However approval of the Reichstag was required to declare war, conclude peace or to conclude any treaty that related to German laws.

- Commander-in-chief: The president held "supreme command" of the armed forces.

- Amnesties: The president had the right to confer amnesties.

Emergency powers

The Weimar constitution granted the president sweeping powers in the event of a crisis. Article 48 empowered the president, if "public order and security [were] seriously disturbed or endangered" to "take all necessary steps to re-establish law and order". These permissible steps included the use of armed force and the suspension of many of the civil rights otherwise guaranteed by the constitution. Most importantly, the president could take over the legislative powers of the Reichstag by issuing Notverordnungen, (emergency decrees) which had the same rank as conventional acts of parliament.

The Reichstag had to be informed immediately of any measures taken under Article 48 and had the right to reverse any such measures. Even so, during the Weimar period the article was used to effectively by-pass parliament. Furthermore, although the article was intended for use only in an extraordinary emergency the article was invoked many times, even before 1933. An additional special power conferred on the Reichspräsident by the constitution was authority to use armed force to oblige a state government to cooperate if it failed to meet its obligations under the constitution or under federal law.

Powers in practice

The Weimar constitution created a system in which the cabinet was answerable to both the president and the legislature. This meant that the parliament had the power to make a government retreat without the burden to create a new one. Ebert and Hindenburg (initially) both attempted to appoint cabinets that enjoyed the confidence of the Reichstag. Most of the Weimar governments were minority cabinets of the centrist parties tolerated by the social democrats or the conservatives.

Ebert (especially in 1923) and Hindenburg (from 1930 onwards) supported governments also by presidential decrees. The last four cabinets of the republic (Brüning I and II, Papen, Schleicher) are even called "presidential" cabinets (Präsidialkabinette) because the presidential decrees more and more replaced the Reichstag legislature. Under Brüning the social democrats still tolerated the government by not supporting motions that revoked the decrees, but since Papen (1932) they refused to do so. This made Hindenburg dismiss the parliament twice in order to "buy" time without a working Parliament.

Removal and succession

The Weimar constitution did not provide for a vice presidency. If the president died or left office prematurely a successor would be elected. During a temporary vacancy, or in the event that the president was "unavailable", the powers and functions of the presidency passed to the chancellor.

The provisions of the Weimar constitution for the impeachment or deposition of the president are similar to those found in the Constitution of Austria. The Weimar constitution provided that the president could be removed from office prematurely by a referendum initiated by the Reichstag. To require such a referendum the Reichstag had to pass a motion supported by at least two-thirds of votes cast in the chamber. If such a proposal to depose the president was rejected by voters the president would be deemed to have been re-elected and the Reichstag would be automatically dissolved.

The Reichstag also had authority to impeach the president before the Staatsgerichtshof, a court exclusively concerned with disputes between state organs. However it could only do this on a charge of willfully violating German law; furthermore the move had to be supported by a two-thirds majority of votes cast, at a meeting with a quorum of two-thirds of the total number of members.

History

The Reichspräsident was established as a kind of Ersatzkaiser, that is, a substitute for the monarch who had reigned in Germany until 1918. The new president's role was therefore informed, at least in part, by that played by the Kaiser under the system of constitutional monarchy being replaced. Hugo Preuss, the writer of the Weimar constitution, is said to have accepted the advice of Max Weber as to the term of office and powers of the presidency, and the method by which the president would be elected. The structure of the relationship between the Reichspräsident and Reichstag is said to have been suggested by Robert Redslob.

On 11 February 1919, the National Assembly elected Friedrich Ebert of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) as the first Reich President by 379 votes to 277. While in office he used emergency decrees on a number of occasions, including to suppress the Kapp Putsch in 1920. His term came to an abrupt end with his death in 1925. In the election that followed, Hindenburg was eventually settled on as the candidate of the political right, while the Weimar coalition united behind Wilhelm Marx of the Centre Party. Many on the right hoped that once in office Hindenburg would destroy Weimar democracy from the inside but in the years that followed his election Hindenburg never attempted to overthrow the Weimar constitution.

In March 1930, Hindenburg appointed Heinrich Brüning to head the first "presidential cabinet", which did not enjoy the support of the Reichstag. In July Hindenburg adopted the national budget by decree and, when the Reichstag reversed this act, he dissolved the legislature. The years that followed would see an explosion of legislation by decree, where previously this power had been used only occasionally.

In March 1932, Hindenburg, although suffering from the onset of senility, decided to stand for re-election. Adolf Hitler was his major opponent but Hindenburg won the election by a substantial margin. In June he replaced Brüning as chancellor with Franz von Papen and again dissolved the Reichstag, before it could adopt a vote of no confidence. After reconvening it was again dissolved in September.

After briefly appointing General Kurt von Schleicher as chancellor in December, Hindenburg responded to growing civil unrest and Nazi activism by appointing Hitler as chancellor in January, 1933. A parliamentary dissolution followed after which Hitler's government, with the aid of another party, were able to command the support of a majority in the Reichstag. On 23 March the Reichstag adopted the Enabling Act, which effectively brought an end to democracy. From this point onwards almost all political authority was exercised by Hitler.

Hitler's government issued a law providing that upon Hindenburg's death (which occurred in August 1934) merging the offices of President and Chancellor in Hitler's person.[4] However, Hitler now styled himself only Führer und Reichskanzler ("Leader and Chancellor"), not using the title of Reichspräsident. The law was "approved" by a staged referendum on 19 August.

Hitler committed suicide on 30 April 1945, as World War II in Europe drew to a close. In his Final Political Testament, Hitler intended to split again the two offices he had merged: he appointed Karl Dönitz as new President, and propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels was to succeed him as Chancellor. Goebbels committed suicide shortly after Hitler and within days Dönitz ordered Germany's military (not political) surrender on the 7 May, which ended the war in Europe. He had by then appointed Ludwig von Krosigk as head of government and the two attempted to gather together a government. However this government was not recognised by the Allied powers and was dissolved when its members were captured and arrested by British forces on 23 May at Flensburg.

On 5 June 1945, the four occupying powers signed a document creating the Allied Control Council, that did not mention the name of the previous German government.

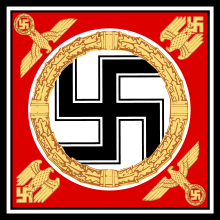

Presidential Standards

.svg.png) 1919–1921

1919–1921 1921–1926

1921–1926 1926–1933

1926–1933 1933–1934

1933–1934 1934–1945

1934–1945

See also

References

- Chapter 4, Presidents and Assemblies, Matthew Soberg Shugart and John M. Carey, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- ↑ Veser, Ernst (1997). "Semi-Presidentialism-Duverger's concept: A New Political System Model" (PDF). Journal for Humanities and Social Sciences. Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences, Taiwan. 11 (1): 39–60. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. United States: University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). French Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- 1 2 Gesetz über das Staatsoberhaupt des Deutschen Reichs, 1 August 1934:

"§ 1 The office of the Reichspräsident is merged with that of the Reichskanzler. Therefore the previous rights of the Reichspräsident pass over to the Führer and Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler. He names his deputy."