Red coat (military uniform)

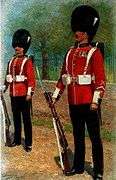

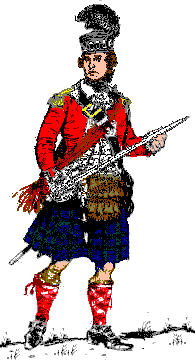

Red coat or Redcoat is a historical item of military clothing used widely, though not exclusively worn, by most regiments of the British Army from the 17th to the 20th centuries.[1] From the mid-17th century to the 19th century, the uniform of most British soldiers (apart from artillery, rifles and light cavalry) included a madder red coat or coatee. From 1873 onwards, the more vivid shade of scarlet was adopted for all ranks, having previously been worn only by officers, sergeants and all ranks of some cavalry regiments.[2]

History

New Model Army useage

The Red Coat has evolved from being the British infantryman's normally worn uniform to a garment retained only for ceremonial purposes. Its official adoption dates from February 1645, when the Parliament of England passed the New Model Army ordinance. The new English Army was formed of 22,000 men, divided into 12 foot regiments of 600 men each, one dragoon regiment of 1000 men, and the artillery, consisting of 900 guns. The infantry regiments wore coats of Venetian red with white facings. A contemporary comment on the New Model Army dated 7 May 1645 stated "the men are Redcoats all, the whole army only are distinguished by the several facings of their coats".[3][4]

Early instances

There had been instances of red military clothing pre-dating its general adoption by the New Model Army. The uniforms of the Yeoman of the Guard (formed 1485) and the Yeomen Warders (also formed 1485) have traditionally been in Tudor red and gold.[4]:3 The Gentlemen Pensioners of James I (now the Gentlemen-at-Arms) had worn red with yellow feathers.[5] At Edgehill, the first battle of the Civil War, the King's people had worn red coats, as had at least two Parliamentary regiments".[6] However none of these examples constituted the national uniform that the red coat was later to become.[4]

Ireland

In Ireland during the reign of Elizabeth, the soldiers of the queen's Lord Lieutenant of Ireland were on occasion referred to as "red coats" by the native Irish, from the colour of their clothing. As early as 1561 the Irish named a victory over these royal troops as Cath na gCasóga Dearga, literally meaning 'The Battle of the Red Cassocks' but usually translated as the Battle of the Red Sagums – sagum being a cloak.[7] Note the Irish word is casóg ("cassock") but the word may be translated as coat, cloak, or even uniform, in the sense that all of these troops were uniformly attired in red. That the term redcoat was brought to Europe and elsewhere by Irish emigrants is evidenced by Philip O'Sullivan Beare, one of the many thousands of fugitives from Tudor and early Stuart Ireland, who mentions the 'Battle of the Redcoats' event in his 1621 history of the Tudor conquest, written in Latin in Spain. He wrote of it as "that famous victory which is called 'of the red coats' [illam victoriam quae dicitur 'sagorum rubrorum'] because among others who fell in battle were four hundred soldiers lately brought from England and clad in the red livery of the viceroy".[8]

O'Sullivan alludes to two other encounters in which the Irish won the day against English 'red coats'. One concerns an engagement, twenty years later in 1581, during the Second Desmond Rebellion, in which he says "a company of English soldiers, distinguished by their dress and arms, who were called "red coats" [Vestibus et armis insignis erat cohors Anglorum quae "Sagorum rubrorem" nominabantur], and being sent to war [in Ireland] by the Queen were overwhelmed near Lismore by John Fitzedmund Fitzgerald, the seneschal".[9] The other relates to a rout by William Burke, Lord of Bealatury in 1599 of "English recruits clad in red coats" (qui erant tyrones Angli sagis rubris induti).[10]

English sources confirm that Crown troops in Ireland wore red coats/cloaks/uniforms/clothing. In 1584 the Lords and Council informed the Sheriffs and Justices of Lancashire who were charged with raising 200 foot for service in Ireland that they should be furnished with "a cassocke of some motley, sad grene coller, or russett".[11] Seemingly, russet was chosen. Again, in the summer of 1595, the Lord Deputy William Russell, 1st Baron Russell of Thornhaugh writing to William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley about the relief of Enniskillen, mentions that the Irish rebel Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone had "300 shot in red coats like English soldiers" – the inference being that English soldiers in Ireland were distinguished by their red uniforms.[12]

Appearance in continental battles

Outside of Ireland, the English Red Coat made its first appearance on a European continental battlefield at the Battle of the Dunes in 1658. A Protectorate army had been landed at Calais the previous year and "every man had a new red coat and a new pair of shoes".[13] The English name from the battle comes from the major engagement carried out by the "red-coats". To the surprise of continental observers they stormed sand-dunes 150 feet (46 m) high fighting experienced Spanish soldiers from their summits with musket fire and push of pike.[14][15]

Post Restoration

The adoption and continuing use of red by most British/English soldiers after The Restoration (1660) was the result of circumstances rather than policy, including the relative cheapness of red dyes.[16] Red was by no means universal at first, with grey and blue coats also being worn.[4]:16 There is no known basis for the myth that red coats were favoured because they did not show blood stains. Blood does in fact show on red clothing as a black stain.

Prior to 1707 colonels of regiments made their own arrangements for the manufacture of uniforms under their command. This ended when a royal warrant of 16 January 1707 established a Board of General Officers to regulate the clothing of the army. Uniforms supplied were to conform to the "sealed pattern" agreed by the board.[4]:47–48 The style of the coat tended to follow those worn by other European armies. The long coat worn with a white or buff coloured waistcoat[17] was discontinued in 1797 in favour of a tight-fitting coatee fastened with a single row of buttons, with white lace loops on either side.[18] Following the discomfort experienced by troops in the Crimean War, a more practical tunic was introduced in 1855, initially in the French double breasted style, but replaced by a single breasted version in the following year.[19]

18th–19th centuries

From an early stage red coats were lined with contrasting colours and turned out to provide distinctive regimental facings (lapels, cuffs and collars).[20] Examples were blue for the 8th Regiment of Foot, green for the 5th Regiment of Foot, yellow for the 44th Regiment of Foot and buff for the 3rd Regiment of Foot. 1747 saw the first of a series of clothing regulations and royal warrants that set out the various facing colours and distinctions to be borne by each regiment.[21] An attempt at standardisation was made following the Childers Reforms of 1881, with English and Welsh regiments having white, Scottish yellow, Irish green and Royal regiments dark blue. However some regiments were subsequently able to obtain the reintroduction of historic facing colours that had been uniquely theirs.[22][23]

British soldiers fought in scarlet tunics for the last time at the Battle of Gennis in the Sudan on 30 December 1885. They formed part of an expeditionary force sent from Britain to participate in the Nile Campaign of 1884-85, wearing the "home service uniform" of the period including scarlet tunics, although some regiments sent from India were in khaki drill.[24] A small detachment of infantry which reached Khartoum by steamer on 28 January 1885 were ordered to fight in their red coats in order to let the Mahdist rebels know that the real British forces had arrived.[25]

20th century

Even after the adoption of khaki service dress in 1902, most British infantry regiments (81 out of 85) and some cavalry regiments (12 out of 31) [26] continued to wear scarlet tunics on parade and for off-duty "walking out dress", until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.[27] While nearly all technical and support branches of the army wore dark blue, the Royal Engineers had worn red since the Peninsular War in order to draw less fire when serving amongst red-coated infantry.[28]

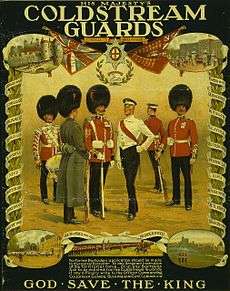

Scarlet tunics ceased to be general issue upon British mobilisation in August 1914. The Brigade of Guards resumed wearing their scarlet full dress in 1920 but for the remainder of the army red coats were only authorised for wear by regimental bands and officers in mess dress or on certain limited social or ceremonial occasions (notably attendance at court functions or weddings).[29][30][31] The reason for not generally reintroducing the distinctive full dress was primarily financial, as the scarlet cloth requires expensive cochineal dye.

As late as 1980, consideration was given to the reintroduction of scarlet as a replacement for the dark blue "No. 1 dress" and khaki "No. 2 dress" of the modern British Army, using cheaper and fadeless chemical dyes instead of cochineal. Surveys of serving soldiers' opinion showed little support for the idea and it was shelved.[32]

Royal Marines

See also: Uniforms of the Royal Marines

Red coats were first worn by British sea-going regiments when adopted by The Prince of Denmark's Regiment in 1686.[33] Thereafter red coatees became the normal parade and battle dress for marine infantry, although the staining effects of salt spray meant that white fatigue jackets and subsequently blue undress tunics were often substituted for shipboard duties. The Royal Marine Artillery wore dark blue from their creation in 1804. The scarlet full-dress tunics of the Royal Marine Light Infantry were abolished in 1923 when the two branches of the Corps were amalgamated and dark blue became the universal uniform colour for both ceremonial and ordinary occasions.[34]

Modern use in Commonwealth armies

In the modern British army, scarlet is still worn by the Foot Guards, the Life Guards, and by some regimental bands or drummers for ceremonial purposes. Officers and NCOs of those regiments which previously wore red retain scarlet as the colour of their "mess" or formal evening jackets. Some regiments turn out small detachments, such as colour guards, in scarlet full dress at their own expense. e.g. the Yorkshire Regiment before amalgamation. The Royal Gibraltar Regiment has a scarlet tunic in its winter dress.

Scarlet is also retained for some full dress, military band or mess uniforms in the modern armies of a number of the countries that made up the British Empire. These include the Australian, Jamaican, New Zealand, Fiji, Canadian, Kenyan, Ghanaian, Indian, Singaporean, Sri Lankan and Pakistani armies.[35] The Royal Canadian Mounted Police also wear a Red Serge jacket, based on a British military pattern tunic.

Red coat as a symbol

The epithet "redcoats" is familiar throughout much of the former British Empire, even though this colour was by no means exclusive to the British Army. The entire Danish Army wore red coats up to 1848 and particular units in the German, French, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, Bulgarian and Romanian armies retained red uniforms until 1914 or later. Amongst other diverse examples, Spanish hussars, Japanese Navy and United States Marine Corps bandsmen, and Serbian generals had red tunics as part of their gala or court dress during this period. In 1827 United States Artillery company musicians were wearing red coats as a reversal of their branch facing colour.[36] However the extensive use of this colour by British, Indian and other Imperial soldiers over a period of nearly three hundred years made red uniform a veritable icon of the British Empire. The significance of military red as a national symbol was endorsed by King William IV (reigned 1830–1837) when light dragoons and lancers had scarlet jackets substituted for their previous dark blue, hussars adopted red pelisses and even the Royal Navy were obliged to adopt red facings instead of white. Most of these changes were reversed under Queen Victoria (1837–1901). A red coat and black tricorne remains part of the ceremonial and out-of-hospital dress for in-pensioners at the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

American Revolution

In the United States, "Redcoat" is associated in cultural memory with the British soldiers who fought against the colonists during the American Revolutionary War: the Library of Congress possesses several examples of the uniforms the British Army used during this time.[37] Most soldiers that fought the colonists wore the red coat though the Hessian mercenaries and some locally recruited loyalist units had blue or green clothing.

Accounts of the time usually refer to British soldiers as "Regulars" or "the King's men", however, there is evidence of the term "red coats" being used informally, as a colloquial expression. During the Siege of Boston, on 4 January 1776, Gen. George Washington uses the term "red coats" in a letter to Joseph Reed.[38] In an earlier letter dated 13 October 1775, Washington used a variation of the expression, stating, "whenever the Redcoat gentry pleases to step out of their Intrenchments."[39] Major General John Stark of the Continental Army was purported to have said during the Battle of Bennington (16 August 1777), "There are your enemies, the Red Coats and the Tories. They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!"[40]

Other pejorative nicknames for British soldiers included "bloody backs" (in a reference to both the colour of their coats and the use of flogging as a means of punishment for military offences) and "lobsters" (most notably in Boston around the time of the Boston Massacre,[41] The earliest reference to the association with the lobster appears in 1740, just before the French and Indian War).[37]

Rationale for red

From the modern perspective, the retention of a highly conspicuous colour such as red for active service appears inexplicable and foolhardy, regardless of how striking it may have looked on the parade ground. However, in the days of the musket (a weapon of limited range and accuracy) and black powder, battle field visibility was quickly obscured by clouds of smoke. Bright colours provided a means of distinguishing friend from foe without significantly adding risk. Furthermore, the vegetable dyes used until the 19th century would fade over time to a pink or ruddy-brown, so on a long campaign in a hot climate the colour was less conspicuous than the modern scarlet shade would be.[42] As battles of the time were also commonly fought in large, conspicuous lines and columns on the battlefield with volley fire, the individual soldier was not a target by himself, making the obviousness of his presence immaterial.

As noted above, no historical basis can be found for the suggestion that the colour red was favoured because of the supposedly demoralising effect of blood stains on a uniform of a lighter colour. In his book British Military Uniforms (Hamylyn Publishing Group 1968), the military historian W.Y. Carman traces in considerable detail the slow evolution of red as the English soldier's colour, from the Tudors to the Stuarts. The reasons that emerge are a mixture of financial (cheaper red, russet or crimson dyes), cultural (a growing popular sense that red was the sign of an English soldier),[43] and simple chance (an order of 1594 is that coats "be of such colours as you can best provide").

Before the Tudor period, red frequently appeared in the cloth livery provided for the household personnel—including guard troops—of many European Royal Houses and Italian or Church principalities. Red or purple had provided a rich distinction for senior clerics through the Middle Ages in the hierarchy of colours distinguishing the Roman Church.

During the English Civil War red dyes were imported in large quantities for use by units and individuals of both sides, though this was the beginning of the trend for long overcoats. The ready availability of red pigment made it popular for military clothing and the dying process required for red involved only one stage. Other colours involved the mixing of dyes in two stages and accordingly involved greater expense; blue, for example, could be obtained with woad, but more popularly it became the much more expensive indigo. In financial terms the only cheaper alternative was the grey-white of undyed wool—an option favoured by the French, Austrian, Spanish and other Continental armies.[44] The formation of the first English standing army (Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army in 1645) saw red clothing as the standard dress. As Carman comments "The red coat was now firmly established as the sign of an Englishman".[45]

On traditional battlefields with large engagements, visibility was not considered a military disadvantage until the general adoption of rifles in the 1850s, followed by smokeless powder after 1880. The value of drab clothing was quickly recognised by the British Army, who introduced khaki drill for Indian and colonial warfare from the mid-19th century on. As part of a series of reforms following the Second Boer War, (which had been fought in this inconspicuous clothing of Indian origin) a darker khaki serge was adopted in 1902 for service dress in Britain itself. From then on, the red coat continued as a dress item only, retained for reasons both of national sentiment and its value in recruiting. The British military authorities were more practical in their considerations than their French counterparts, who incurred heavy casualties by retaining highly visible blue coats and red trousers for active service until several months into World War I.[46]

Material used

Whether scarlet or red, the uniform coat has historically been made of wool with a lining of a loosely woven wool known as bay to give shape to the garment. The modern scarlet wool is supplied by Abimelech Hainsworth and is much lighter than the traditional material, which was intended for hard wear on active service.[44]

The cloth for private soldiers used up until the late 18th century was plain weave broadcloth weighing 16 ounces per square yard (540 g/m2), made from coarser blends of English wool. The weights often quoted in contemporary documents are given per running yard, though; so for a cloth of 54 inches (140 cm) width a yard weighed 24 ounces (680 g). This sometimes leads to the erroneous statement that the cloth weighed 24 oz per square yard.

Broadcloth is so called not because it is finished wide, 54 inches not being particularly wide, but because it was woven nearly half as wide again and shrunk down to finish 54 inches. This shrinking, or milling, process made the cloth very dense, bringing all the threads very tightly together, and gave a felted blind finish to the cloth. These factors meant that it was harder wearing, more weatherproof and could take a raw edge; the hems of the garment could be simply cut and left without hemming as the threads were so heavily shrunk together as to prevent fraying.

Officers' coats were made from superfine broadcloth; manufactured from much finer imported Spanish wool, spun finer and with more warps and wefts per inch. The result was a slightly lighter cloth than that used for privates, still essentially a broadcloth and maintaining the characteristics of that cloth, but slightly lighter and with a much finer quality finish.

The dye used for privates' coats of the infantry, guard and line, was rose madder. A vegetable dye, it was recognised as economical, simple and reliable and remained the first choice for lower quality reds from the ancient world until chemical dyes became cheaper in the latter 19th century.

Infantry sergeants, some cavalry regiments and many volunteer corps (which were often formed from prosperous middle-class citizens who paid for their own uniforms) used various mock scarlets; a brighter red but derived from cheaper materials than the cochineal used for officers coats. Various dye sources were used for these middle quality reds, but lac, pigment extracted from the vegetable resin shellac, was the most common basis. The noncommissioned officer's red coat issued under the warrant of 1768, was dyed with a mixture of madder-red and cochineal to produce a "lesser scarlet"; brighter than the red worn by other ranks but cheaper than the pure cochineal dyed garment purchased by officers as a personal order from military tailors.[47]

Officers' superfine broadcloth was dyed true scarlet with cochineal, a dye derived from insects. This was a more expensive process but produced a distinctive colour that was the speciality of 18th-century English dyers.

Other military usage

Bolivia

The Bolivian Colorados Regiment wear red tunics on ceremonial occasions - colorado means red in Spanish.

Brazil

The Brazilian Marine Corps also wear red coats as part of their ceremonial uniforms.

Canada

Detachments from some units of the Canadian Forces wear ceremonial scarlet uniforms for special occasions or parades. In addition the scarlet uniform is the ceremonial dress for cadets at the Royal Military College of Canada. It also serves as the basis for the dress uniform of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Denmark-Norway

The combined Danish-Norwegian army wore red uniforms from the 17th century until Norway entered union with Sweden in 1814. Most Danish Army infantry, cavalry and artillery regiments continued to wear red coats until they were replaced by dark blue service tunics in 1848. The modern Danish Royal Life Guards still wears the historic red tunics on special ceremonial occasions.[48]

France

The Irish Brigade of the French Army (1690-1792) wore red coats supposedly to show their origins and continued loyalty to the cause of Jacobitism. Red coats were also worn by the Swiss Guard and other Swiss mercenary regiments in the French Army from the mid-17th to early 19th centuries. The North African spahi regiments wore red jackets until disbanded in 1962.

Italy

Redshirts (Italian Camicie rosse) or Red coats (Italian Giubbe Rosse) is the name given to the volunteers who followed Giuseppe Garibaldi. The name derived from the color of their shirts or loose fitting blouses, as complete uniforms were beyond the financial resources of the Italian patriots.

Netherlands

The Garderegiment Fuseliers Prinses Irene of the Royal Netherlands Army wear red tunics based on the British style, in commemoration of the unit's foundation in exile in the United Kingdom during World War II.[49]

Paraguay

All branches of the Paraguayan Army wore red jackets or blouses during the War of the Triple Alliance 1864-70.[50]

Poland

The Royal Polish Guards (Polish: Gwardia Piesza Koronna), during the times of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, wore a red cloth jacket with white lapels and a blue or turquoise vest. During the colder seasons, all soldiers were given red coats, similar to those of the contemporary British army, made of wool.[51]

United States

Members of the United States Marine Band wear red uniforms for performances at the White House and elsewhere. This is a rare survival of the common 18th-century practice of having military bandsmen wear coats in reverse colours to the rest of a given unit (United States Marines wear blue/black tunics with red facings so United States Marine bandsmen wear red tunics with blue/black facings). Members of the US Army's "Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps" also wear red uniforms, heavily based on the dress uniforms of the United States Army during the American Revolution.

Venezuela

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Ejército Libertador (the Army of Liberation), inherited from the British Legion the red hussar cavalry uniforms used by the Company of Honor Guard of the Liberator Simon Bolivar.

In present-day Venezuela the red coat is part of the parade uniforms of the Regimiento de Guardia de Honor (Regiment of Presidential Guards);[52] the Compañia de Honor "24 de Junio" (Company of Honor "24 de Junio")[53] and the new National Militia Bolivariana.[54][55]

Gallery

17th century

|

18th century

|

19th century

|

20th–21st century

|

See also

References

- ↑ page 868, Concise Oxford Dictionary 1982, ISBN 0-19-861131-5

- ↑ Major R.M. Barnes A History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army", Sphere Books Ltd London 1972, p.257

- ↑ Peter Young & Richard Holmes, page 43 "The English Civil War", ISBN 978-1-84022-222-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lawson, Cecil C P (1969) [1940]. A History of the Uniforms of the British Army, Volume I:From the Beginning to 1760. London: Kaye & Ward. ISBN 978-0-7182-0814-1.

- ↑ W.Y. Carmen, page 15 "British Military Uniforms from Contemporary Pictures"

- ↑ Peter Young & Richard Holmes, page 42 "The English Civil War", ISBN 978-1-84022-222-7

- ↑ Abbé MacGeoghegan History of Ireland, Ancient and Modern (Paris, 1758), trans. P. O'Kelly (1832), Vol. III, p.109.

- ↑ Historiae Catholicae Iberniae Compendium by Philip O'Sullivan Beare (1621), Tome II, Bk IV, Chap III, translated as Ireland Under Elizabeth by Matthew J. Byrne (1903). See p. 5 of Byrne's translation

- ↑ Historiae Catholicae Iberniae Compendium by Philip O'Sullivan Beare (1621), Tome II, Bk IV, Chap XV, translated as Ireland Under Elizabeth by Matthew J. Byrne (1903). See p. 27 of Byrne's translation

- ↑ Historiae Catholicae Iberniae Compendium by Philip O'Sullivan Beare (1621), Tome III, Bk V, Chap IV, translated as Ireland Under Elizabeth by Matthew J. Byrne (1903). See p. 118 of Byrne's translation

- ↑ Letter of the Lords in Council to the Sheriffs & Justices of Lancashire, dated 16 August 1584, concerning the raising and outfitting of 200 foot. Quoted in Francis Peck Desiderata Curiosa (1779), Vol I, Lib IV, No. LIII, p. 155.

- ↑ 'Elizabeth I: volume 180, June 1595', in Calendar of State Papers, Ireland, 1592-1596, ed. Hans Claude Hamilton (London, 1890), p. 322.

- ↑ W.Y. Carmen, page 17 "British Military Uniforms from Contemporary Pictures"

- ↑

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Atkinson, Charles Francis (1911). "Fronde, The". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 248.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Atkinson, Charles Francis (1911). "Fronde, The". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 248. - ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 634. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- ↑ W.Y. Carman. British Military Uniforms from Contemporary Pictures. Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. 1957.

- ↑ Kannik, Preben (1968), Military Uniforms of the World in Colour, Blandford Press Ltd, ISBN 0-71370482-9 (p. 130)

- ↑ Kannik p. 188

- ↑ Beckett, Ian F W (2007), Discovering British Regimental Traditions Shire Publications Ltd ISBN 978-0-7478-0662-2 (p. 89)

- ↑ Holmes, Richard. Redcoat. The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket. p. 184. ISBN 0-00-653152-0.

- ↑ "Regulation for the Uniform Cloathing of the Marching Regiments of Foot" reproduced in Edwards, T J (1953). Standards, Guidons and Colours of the Commonwealth Forces. Aldershot: Gale & Polden. pp. 191–193.

No part of the Cloathing or Ornaments of the Regiments to be altered, after the following Regulations are put into execution by His Majesty's permission.

- ↑ W.Y. Carman "Uniforms of the British Army — the Infantry Regiments, ISBN 978-0-86350-031-2, p.33

- ↑ Funcken, Fred; Funcken, Liliane (1976). British Infantry Uniforms from Marlborough to Wellington. London: Ward Lock. pp. 20–24, 34–36. ISBN 978-0-7063-5181-1.

- ↑ Mollo, John. Military Fashion. pp. 215–216. ISBN 0-214-65349-8.

- ↑ Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1995) The Colonial Wars Sourcebook, London: Arms and Armour Press, ISBN 978-1-85409-196-3, p. 35

- ↑ Major R.M. Barnes, "A History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army", Sphere Books Ltd London 1972, pages 295-302

- ↑ Holmes, Richard. Redcoat. The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket. p. 192. ISBN 0-00-653152-0.

- ↑ Major R.M. Barnes, "Military Uniforms of Britain & the Empire", Sphere Books Ltd London 1972, page 157

- ↑ "Army Uniform. Report of Sir A. Murray's Committee". The Times. 30 October 1919. p. 12.

- ↑ "Foot Guards in Full Dress Again". The Times. 2 July 1920. p. 9.

- ↑ "Guards' Uniform Changes. Pre-War Style Revised with Economies". The Times. 31 July 1920. p. 15.

- ↑ Smith, Major D.J. The British Army 1965-80. p. 40. ISBN 0-85045-273-2.

- ↑ Charles C. Stadden, page 12 "Uniforms of the Royal Marines", ISBN 0-9519342-2-8

- ↑ Charles C. Stadden, page 91 "Uniforms of the Royal Marines", ISBN 0-9519342-2-8

- ↑ Rinaldi d'Ami, "World Uniforms in Colour — Volume 2: Nations of America, Africa, Asia and Oceania, ISBN 978-0-85059-040-1

- ↑ Set No 1 "The American Soldier", Office Cheief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1975

- 1 2 Richard Holmes, page 2 "Redcoat: The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket", W.W. Norton and Co., ISBN 0393052117

- ↑ The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, Vol. 4: To JOSEPH REED Cambridge, January 4, 1776. "..the red coats I mean..."

- ↑ The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, Vol. 4: To JOHN AUGUSTINE WASHINGTON Camp at Cambridge, October 13, 1775. "whenever the red Coat gentry pleases to step out of their Intrenchments."

- ↑ Crockett, Walter Hill (1921). Vermont: The Green Mountain State, volume 2. New York: The Century history company.

- ↑ owing to the fact that a boiled American lobster is always bright red and near perfect match to the colour of the late 18th century uniform.

- ↑ John Mollo Military Fashion, ISBN 978-0-214-65349-0

- ↑ W.Y. Carman, pages 13, 18, 25 & 33 "British Military Uniforms From Contemporary Pictures", Hamlyn Publishing Group 1968

- 1 2 Tim Newark Brassey's Book of Uniforms, ISBN 978-1-85753-243-2

- ↑ Carman 1968, p. 24.

- ↑ Barbara W. Tuchman, page 55 The Guns of August, Constable and Co. Ltd 1962

- ↑ Franklin, Carl. British Army Uniforms from 1751-1783. pp. 117 & 119. ISBN 978-1-84884-690-6.

- ↑ Kannik p. 253

- ↑ Kannik pp. 254-255

- ↑ Esposito, Gabriel. Armies of the War of the Triple Alliance 1864-70. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4728-0725-0.

- ↑ "Muzeum Wojska Polskiego w Warszawie". muzeumwp.pl.

- ↑ Regiment of Presidential Guards

- ↑ "Campo de Carabobo". 8 January 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ↑ Hatillo, Psuv El (20 April 2010). "Psuv El Hatillo: Chávez y despliegue militar en el desfile del Bicentenario". Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ↑ "Red de Círculos Bolivarianos asegura que la oposición está dolida por celebración del Bicentenario en Noticias24.com". Retrieved 3 January 2017.

Sources

- Barnes, Major R. M. (1951). History of the Regiments & Uniforms of the British Army. Seeley Service & Co.

- Barthorp, Michael (1982). British Infantry Uniforms Since 1660. Blandford Press. ISBN 978-1-85079-009-9.

- Carman, W.Y. (1968). British Military Uniforms from Contemporary Pictures. Hamlyn Publishing Group.

.jpg)

%2C_1891.jpg)