Presidency of Ronald Reagan

| ||

|---|---|---|

40th President of the United States Policies Appointments First Term Second Term Post-Presidency |

||

The presidency of Ronald Reagan began on January 20, 1981, when Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican, took office as the 40th United States president following a landslide win over Democratic incumbent President Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election. Reagan was succeeded by his vice president, George H. W. Bush, who won the 1988 presidential election with Reagan's support.

Domestically, Reagan introduced several tax cuts and sought to cut non-military spending. The economic policies enacted in 1981, known as "Reaganomics", were inspired by supply-side economics. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 simplified the tax code, reducing rates while removing several tax breaks. Reagan also appointed more federal judges than any other president, including four Supreme Court Justices. Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which enacted sweeping changes U.S. immigration law, and the administration escalated the "War on Drugs".

Reagan's foreign policy stance was resolutely anti-communist; its plan of action, known as the Reagan Doctrine, sought to roll back the global influence of the Soviet Union in an attempt to end the Cold War. Under this doctrine, the administration initiated a massive buildup of the military, promoted new technologies such as missile defense systems, and, in 1983, undertook an invasion of Grenada, the first major overseas action by U.S. troops since the end of the Vietnam War. It also controversially granted aid to paramilitary forces seeking to overthrow leftist governments, particularly in war-torn Central America and Afghanistan. During Reagan's second term, he sought closer relations with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, and the two leaders signed the INF Treaty, a major arms control agreement. The Reagan administration engaged in covert arms sales to Iran in order to fund the Contra rebels in Nicaragua that were fighting to overthrow their socialist government. The resulting Iran–Contra affair resulted in the conviction or resignation of several administration officials.

Leaving office in 1989, Reagan held an approval rating of sixty-eight percent, matching those of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and later Bill Clinton, as the highest ratings for departing presidents in the modern era.[1] Historians and political scientists generally rank Reagan as an above-average president. Due to Reagan's impact on public discourse and advocacy of American conservatism, some historians have described the period during and after his presidency as the Reagan Era.

1980 election

Reagan, who had served as Governor of California from 1967 to 1975, narrowly lost the 1976 Republican presidential primaries to incumbent President Gerald Ford. With the defeat of Ford by Democrat Jimmy Carter in the 1976 election, Reagan immediately became the front-runner for the 1980 Republican presidential nomination.[2] A darling of the conservative movement, Reagan faced more moderate Republicans such as George H. W. Bush, Howard Baker, and Bob Dole in the 1980 Republican presidential primaries. After Bush won the Iowa caucuses, he became Reagan's primary challenger, but Reagan won the New Hampshire primary and most of the following primaries, gaining an insurmountable delegate lead by the end of March 1980. Ford was Reagan's first choice for his running mate, but Reagan backed away from the idea out of the fear of a "copresidency" in which Ford would exercise an unusual degree of power. Reagan instead chose Bush, and the Reagan-Bush ticket was nominated at the 1980 Republican National Convention. Meanwhile, Carter won the Democratic nomination, defeating Ted Kennedy's primary challenge. Polls taken after the party conventions showed a tied race between Reagan and Carter. An independent candidate, former Republican Congressman John B. Anderson, also appealed to numerous moderates.[3]

The 1980 general campaign between Reagan and Carter was conducted amid a multitude of domestic concerns and the ongoing Iran hostage crisis. Reagan's campaign stressed some of his fundamental principles: lower taxes to stimulate the economy,[4] less government interference in people's lives,[5] states' rights,[6] and a strong national defense.[7] Reagan won 50.7% of the popular vote and 489 of the 538 electoral votes. Carter won 41% of the popular vote and 49 electoral votes, while Anderson won 6.6% of the popular vote. In the concurrent congressional elections, Republicans took control of the Senate for the first time since the 1950s, while Democrats retained control of the House.

Legislation and programs

Major legislation signed

Other major legislation

- October 2, 1986: Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act: Reagan vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode the veto

- August 4, 1988: Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act: Became law without Reagan's signature

Major treaties

Administration

Cabinet

Judicial appointments

Reagan made four successful (and two unsuccessful) appointments to the Supreme Court during his eight years in office:

- Sandra Day O'Connor – Associate Justice (to replace Potter Stewart),

nominated August 19, 1981 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate September 21, 1981.[8] The first woman on the Supreme Court, O'Connor retired from the Court in 2006, and was generally considered to be a centrist conservative[9] - William Rehnquist – Chief Justice (to replace Warren Burger),

nominated June 20, 1986 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate September 17, 1986.[8] Rehnquist, a member of the conservative wing of the Court,[9] was the second sitting associate justice to be elevated to chief justice (after Edward Douglass White in 1910); such nominations are subject to a separate confirmation process. - Antonin Scalia – Associate Justice (to fill the vacancy left by William Rehnquist's elevation to chief justice),

nominated June 24, 1986 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate September 17, 1986.[8] He was a member of the Court's conservative wing.[9]- Robert Bork – Associate Justice (to replace Lewis F. Powell Jr.),

nominated July 7, 1987, but rejected by the U.S. Senate on October 23, 1987, by a vote of 42 in favor and 58 against confirmation.[8] - Douglas H. Ginsburg – Associate Justice (to replace Lewis F. Powell Jr.),

nomination announced October 29, 1987, but withdrawn November 7, 1987, before it was formally submitted to the U.S. Senate.

- Robert Bork – Associate Justice (to replace Lewis F. Powell Jr.),

- Anthony Kennedy – Associate Justice (to replace Lewis F. Powell Jr.),

nominated November 30, 1987 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate February 3, 1988.[8] Currently the senior member of the Court, he is generally considered to be a centrist conservative.[9]

Reagan also appointed 83 judges to the United States courts of appeals, and 290 judges to the United States district courts. Reagan sought to appoint conservatives to the bench, and many of his appointees were connected with the conservative Federalist Society.[10]

Domestic affairs

Reagan was an advocate of free markets and laissez-faire economics and believed that the U.S. economy was hampered by excessive regulations and social programs. He put aside his campaign promise to cut the federal budget deficit, instead focusing on four priorities: reducing taxes, reducing spending, implementing deregulation, and using monetary policy to fight inflation.[11] In his first inaugural speech, Reagan stated:[12]

In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.

"Reaganomics" and taxation

Reagan implemented policies based on supply-side economics, advocating a laissez-faire philosophy and free-market fiscal policy,[13] seeking to stimulate the economy with large, across-the-board tax cuts.[14][15] Citing the economic theories of Arthur Laffer, Reagan promoted the proposed tax cuts as potentially stimulating the economy enough to expand the tax base, offsetting the revenue loss due to reduced rates of taxation, a theory that entered political discussion as the Laffer curve. Reaganomics was the subject of debate with supporters pointing to improvements in certain key economic indicators as evidence of success, and critics pointing to large increases in federal budget deficits and the national debt.[16]

During Reagan's presidency, federal income tax rates were lowered significantly with the signing of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981,[17] which lowered the top marginal tax bracket from 70% to 50% and the lowest bracket from 14% to 11%. However, Congress passed and Reagan signed into law tax increases of some nature in every year from 1981 to 1987 to continue funding such government programs as Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982 (TEFRA), Social Security, and the Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 (DEFRA).[18][19] The Tax Reform Act of 1986, a bipartisan effort championed by Reagan, simplified the tax code by reducing the number of tax brackets to four and slashing a number of tax breaks. The top rate was dropped to 28%, but capital gains taxes were increased on those with the highest incomes from 20% to 28%. The increase of the lowest tax bracket from 11% to 15% was more than offset by expansion of the personal exemption, standard deduction, and earned income tax credit. The net result was the removal of six million poor Americans from the income tax roll and a reduction of income tax liability at all income levels.[20][21]

The net effect of all Reagan-era tax bills was a 1% decrease in government revenues when compared to Treasury Department revenue estimates from the Administration's first post-enactment January budgets.[22] However, federal income tax receipts increased from 1980 to 1989, rising from $308.7 billion to $549 billion[23] or an average annual rate of 8.2% (2.5% attributed to higher Social Security receipts), and federal outlays grew at an annual rate of 7.1%.[24][25]

Government spending and debt

Further following his opposition to government intervention, Reagan cut the budgets of non-military[26] programs[27] including Medicaid, food stamps, federal education programs[26] and the EPA.[28] While he protected entitlement programs, such as Social Security and Medicare,[29] his administration attempted to purge many people with disabilities from the Social Security disability rolls.[30]

As Reagan was unwilling to match his tax cuts with cuts to defense spending or Social Security, rising deficits became an issue, even after Reagan signed into law several tax increases, including TEFRA and DEFRA.[31] From 1981 to 1989, the national debt rose from $998 billion to $2.857 trillion.[32] In an effort to lower the national debt, Congress passed the Gramm–Rudman–Hollings Balanced Budget Act, which called for automatic spending cuts if Congress was otherwise unable to cut the deficit. However, Congress found ways around the automatic cuts and deficits continued to rise, ultimately leading to the passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990.[33]

Immigration

Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act in 1986. The act made it illegal to knowingly hire or recruit illegal immigrants, required employers to attest to their employees' immigration status, and granted amnesty to approximately three million illegal immigrants who entered the United States before January 1, 1982, and had lived in the country continuously. Critics argue that the employer sanctions were without teeth and failed to stem illegal immigration.[34] Upon signing the act at a ceremony held beside the newly refurbished Statue of Liberty, Reagan said, "The legalization provisions in this act will go far to improve the lives of a class of individuals who now must hide in the shadows, without access to many of the benefits of a free and open society. Very soon many of these men and women will be able to step into the sunlight and, ultimately, if they choose, they may become Americans."[35] Reagan also said, "The employer sanctions program is the keystone and major element. It will remove the incentive for illegal immigration by eliminating the job opportunities which draw illegal aliens here."[35]

War on Drugs

Not long after being sworn into office, Reagan declared more militant policies in the "War on Drugs".[36][37] He promised a "planned, concerted campaign" against all drugs,[38] eventually leading to decreases in adolescent drug use in America.[39][40] As a part of the administration's effort, Reagan's First Lady, Nancy, made the War on Drugs her main cause as First Lady, by founding the "Just Say No" drug awareness campaign.[41]

President Reagan signed a large drug enforcement bill into law in 1986; it granted $1.7 billion to fight drugs, and ensured a mandatory minimum penalty for drug offenses.[41] The bill was criticized for promoting significant racial disparities in the prison population, however, because of the differences in sentencing for crack versus powder cocaine.[41] Critics also charged that the administration's policies did little to actually reduce the availability of drugs or crime on the street, while resulting in a great financial and human cost for American society.[42] Supporters argued that the numbers for adolescent drug users declined during Reagan's years in office.[40]

Foreign affairs

In foreign affairs, Reagan publicly and aggressively rejected détente, choosing instead direct confrontation with the Soviet Union through a policy of "peace through strength", including increased military spending, more confrontational foreign policies against the USSR and, in what came to be known as the Reagan Doctrine, support for anti-communist rebel movements in Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Nicaragua and elsewhere.[43] Reagan later negotiated with Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, and together they succeeded in bringing about a substantial reduction in armaments levels worldwide.[44]

Escalation of the Cold War

Reagan escalated the Cold War, accelerating a reversal from the policy of détente which began in 1979 after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[46] Reagan ordered a massive buildup of the United States Armed Forces and implemented new policies towards the Soviet Union: reviving the B-1 Lancer program that had been canceled by the Carter administration, and producing the MX missile.[47] In response to Soviet deployment of the SS-20, Reagan oversaw NATO's deployment of the Pershing missile in West Germany.[48]

Together with the United Kingdom's prime minister Margaret Thatcher, Reagan denounced the Soviet Union in ideological terms.[49] In a famous address on June 8, 1982, to the Parliament of the United Kingdom in the Royal Gallery of the Palace of Westminster, Reagan said, "the forward march of freedom and democracy will leave Marxism–Leninism on the ash heap of history."[50][51] On March 3, 1983, he predicted that communism would collapse, stating, "Communism is another sad, bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages even now are being written."[52] In a speech to the National Association of Evangelicals on March 8, 1983, Reagan called the Soviet Union "an evil empire."[53]

After Soviet fighters downed Korean Air Lines Flight 007 near Moneron Island on September 1, 1983, carrying 269 people, including Georgia congressman Larry McDonald, Reagan labeled the act a "massacre" and declared that the Soviets had turned "against the world and the moral precepts which guide human relations among people everywhere."[54] The Reagan administration responded to the incident by suspending all Soviet passenger air service to the United States, and dropped several agreements being negotiated with the Soviets, wounding them financially.[54] As a result of the shootdown, and the cause of KAL 007's going astray thought to be inadequacies related to its navigational system, Reagan announced on September 16, 1983, that the Global Positioning System would be made available for civilian use, free of charge, once completed in order to avert similar navigational errors in future.[55][56]

In March 1983, Reagan introduced the Strategic Defense Initiative, a defense project[57] that would have used ground- and space-based systems to protect the United States from attack by strategic nuclear ballistic missiles.[58] Reagan believed that this defense shield could make nuclear war impossible.[57][59] There was much disbelief surrounding the program's scientific feasibility, leading opponents to dub SDI "Star Wars" and argue that its technological objective was unattainable.[57] The Soviets became concerned about the possible effects SDI would have; leader Yuri Andropov said it would put "the entire world in jeopardy."[60] For those reasons, David Gergen, former aide to President Reagan, believes that in retrospect, SDI hastened the end of the Cold War.[61]

End of the Cold War

Until the early 1980s, the United States had relied on the qualitative superiority of its weapons to essentially frighten the Soviets, but the gap had been narrowed.[62] Although the Soviet Union did not accelerate military spending after President Reagan's military buildup,[63] their large military expenses, in combination with collectivized agriculture and inefficient planned manufacturing, were a heavy burden for the Soviet economy.[64] At the same time, Saudi Arabia increased oil production,[65] which resulted in a drop of oil prices in 1985 to one-third of the previous level; oil was the main source of Soviet export revenues.[64] These factors contributed to a stagnant Soviet economy during Gorbachev's tenure.[64]

Reagan recognized the change in the direction of the Soviet leadership with Mikhail Gorbachev, and shifted to diplomacy, with a view to encourage the Soviet leader to pursue substantial arms agreements. Reagan's personal mission was to achieve "a world free of nuclear weapons," which he regarded as "totally irrational, totally inhumane, good for nothing but killing, possibly destructive of life on earth and civilization."[66][67][68] He was able to start discussions on nuclear disarmament with General Secretary Gorbachev.[68] Gorbachev and Reagan held four summit conferences between 1985 and 1988: the first in Geneva, Switzerland, the second in Reykjavík, Iceland, the third in Washington, D.C., and the fourth in Moscow.[69] Reagan believed that if he could persuade the Soviets to allow for more democracy and free speech, this would lead to reform and the end of Communism.[70]

Before Gorbachev's visit to Washington, D.C., for the third summit in 1987, the Soviet leader announced his intention to pursue significant arms agreements.[71] The timing of the announcement led Western diplomats to contend that Gorbachev was offering major concessions to the United States on the levels of conventional forces, nuclear weapons, and policy in Eastern Europe.[71] He and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty) at the White House, which eliminated an entire class of nuclear weapons.[72] The two leaders laid the framework for the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START I; Reagan insisted that the name of the treaty be changed from Strategic Arms Limitation Talks to Strategic Arms Reduction Talks.[67]

When Reagan visited Moscow for the fourth summit in 1988, he was viewed as a celebrity by the Soviets. A journalist asked the president if he still considered the Soviet Union the evil empire. "No," he replied, "I was talking about another time, another era."[73] At Gorbachev's request, Reagan gave a speech on free markets at the Moscow State University.[74] In his autobiography, An American Life, Reagan expressed his optimism about the new direction that they charted and his warm feelings for Gorbachev.[75] In November 1989, ten months after Reagan left office, the Berlin Wall was opened, the Cold War was unofficially declared over at the Malta Summit on December 3, 1989, and two years later, the Soviet Union collapsed.[76]

Reagan Doctrine

Under a policy that came to be known as the Reagan Doctrine, Reagan and his administration also provided overt and covert aid to anti-communist resistance movements in an effort to "rollback" Soviet-backed communist governments in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.[77] Reagan deployed the CIA's Special Activities Division to Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were instrumental in training, equipping and leading Mujahideen forces against the Soviet Army.[78][79] President Reagan's Covert Action program has been given credit for assisting in ending the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan,[80] though some of the United States funded armaments introduced then would later pose a threat to U.S. troops in the 2001 War in Afghanistan.[81] However, in a break from the Carter policy of arming Taiwan under the Taiwan Relations Act, Reagan also agreed with the communist government in China to reduce the sale of arms to Taiwan.[82]

Grenada

The invasion of the Caribbean island Grenada in 1983, ordered by President Reagan, was the first major foreign event of the administration, as well as the first major operation conducted by the military since the Vietnam War. President Reagan justified the invasion by claiming that the cooperation of the island with communist Cuba posed a threat to the United States, and stated the invasion was a response to the illegal overthrow and execution of Grenadian Prime Minister Maurice Bishop, himself a communist, by another faction of communists within his government. After the start of planning for the invasion, the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) appealed to the United States, Barbados, and Jamaica, among other nations, for assistance. The US invasion was poorly done, for it took over 10,000 U.S. forces eight days of fighting, suffering nineteen fatalities and 116 injuries, fighting against several hundred lightly armed policemen and Cuban construction workers. Grenada's Governor-General, Paul Scoon, announced the resumption of the constitution and appointed a new government, and U.S. forces withdrew that December.

While the invasion enjoyed public support in the United States and Grenada[83][84] it was criticized by the United Kingdom, Canada and the United Nations General Assembly as "a flagrant violation of international law".[85] The date of the invasion is now a national holiday in Grenada, called Thanksgiving Day.

South Africa

During Ronald Reagan's presidency South Africa continued to use a non-democratic system of government based on racial discrimination, known as apartheid, in which the minority of white South Africans exerted nearly complete legal control over the lives of the non-white majority of the citizens. In the early 1980s the issue had moved to the center of international attention as a result of events in the townships and outcry at the death of Stephen Biko. Reagan administration policy called for "constructive engagement" with the apartheid government of South Africa. In opposition to the condemnations issued by the US Congress and public demands for diplomatic or economic sanctions, Reagan made relatively minor criticisms of the regime, which was otherwise internationally isolated, and the US granted recognition to the government. South Africa's military was then engaged in an occupation of Namibia and proxy wars in several neighboring countries, in alliance with Savimbi's UNITA. Reagan administration officials saw the apartheid government as a key anti-communist ally.[86]

By late 1985, facing hostile votes from Congress on the issue, Reagan made an "abrupt reversal" on the issue and proposed sanctions on the South African government, including an arms embargo.[87] However, these sanctions were seen as weak by anti-Apartheid activists who were calling for Disinvestment from South Africa.[88] In 1986, Reagan vetoed the tougher sanctions of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, but this was overridden by a bipartisan effort in Congress. By 1990, under Reagan's successor George H. W. Bush, the new South African government of F. W. de Klerk was introducing widespread reforms, though the Reagan administration argued that this was not a result of the tougher sanctions.[89]

Libya bombing

Relations between Libya and the United States under President Reagan were continually contentious, beginning with the Gulf of Sidra incident in 1981; by 1982, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was considered by the CIA to be, along with USSR leader Leonid Brezhnev and Cuban leader Fidel Castro, part of a group known as the "unholy trinity" and was also labeled as "our international public enemy number one" by a CIA official.[90] These tensions were later revived in early April 1986, when a bomb exploded in a Berlin discothèque, resulting in the injury of 63 American military personnel and death of one serviceman. Stating that there was "irrefutable proof" that Libya had directed the "terrorist bombing," Reagan authorized the use of force against the country. In the late evening of April 15, 1986, the United States launched a series of airstrikes on ground targets in Libya.[91][92]

Britain's prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, allowed the U.S. Air Force to use Britain's air bases to launch the attack, on the justification that the UK was supporting America's right to self-defense under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.[92] The attack was designed to halt Gaddafi's "ability to export terrorism," offering him "incentives and reasons to alter his criminal behavior."[91] The president addressed the nation from the Oval Office after the attacks had commenced, stating, "When our citizens are attacked or abused anywhere in the world on the direct orders of hostile regimes, we will respond so long as I'm in this office."[92] The attack was condemned by many countries. By a vote of 79 in favor to 28 against with 33 abstentions, the United Nations General Assembly adopted resolution 41/38 which "condemns the military attack perpetrated against the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya on April 15, 1986, which constitutes a violation of the Charter of the United Nations and of international law."[93]

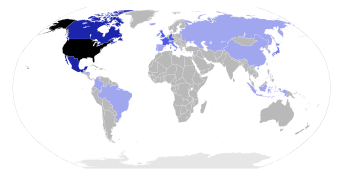

International travel

Reagan made 25 international trips to 26 different countries on four continents—Europe, Asia, North America, and South America—during his Presidency.[94] He made seven trips to continental Europe, three to Asia and one to South America. He is perhaps best remembered for his speeches at the 40th anniversary of the Normandy landings, for his impassioned speech at the Berlin Wall, his summit meetings with Mikhail Gorbachev, and riding horses with Queen Elizabeth II at Windsor Park.

Assassination attempt

On March 30, 1981, only 69 days into the new administration, Reagan, his press secretary James Brady, Washington police officer Thomas Delahanty, and Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy were struck by gunfire from would-be assassin John Hinckley Jr. outside the Washington Hilton Hotel. Although "close to death" at the hospital,[95] Reagan recovered and was released from the hospital on April 11, becoming the first serving U.S. President to survive being wounded in an assassination attempt.[96] The attempt had great influence on Reagan's popularity; polls indicated his approval rating to be around 73%.[97]

Controversies

Iran–Contra affair

Fearing that Communists would take over the Central American nation of Nicaragua if it remained under the leadership of the left-wing Sandinistas, the Reagan administration authorized CIA Director William J. Casey to arm the right-wing Contras early in his tenure. Congress, which favored negotiations between the Contras and Sandinista, passed the 1982 Boland Amendment, prohibiting the CIA and Defense Department from using their budgets to aid to the Contras. Still intent on supporting the Contras, the Reagan administration raised funds for the Contras from private donors and foreign governments.[98]

During his second-term, Reagan sought to find a way procure the release of seven American hostages held by Hezbollah, a Lebanese paramilitary group supported by Iran. The Reagan administration decided to sell American arms to Iran, then engaged in the Iran–Iraq War, in hopes that Iran would pressure Hezbollah to release the hostages. The Reagan administration sold over 2000 missiles to Iran without informing Congress, while Hezollah released four hostages but captured an additional six Americans. On the initiative of Oliver North, an aide on the National Security Council, the Reagan administration redirected the proceeds from the missile sales to the Contras. The transactions became public knowledge in October 1986, resulting in the dismissals of North and National Security Adviser John Poindexter. Reagan also appointed the Tower Commission and Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh to investigate the transactions.[99]

The Iran–Contra scandal as it became known, did serious damage to the Reagan presidency. The investigations were effectively halted when President George H. W. Bush pardoned Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger before his trial began.[100]

Savings and loan crisis

In the savings and loan crisis, 747 financial institutions failed and needed to be rescued with $160 billion in taxpayer dollars.[101] Revisions to the tax code during Reagan's term included the elimination of the "passive loss" provisions that subsidized rental housing. Because this was removed retroactively, it bankrupted many real estate developments which used this tax break as a premise, which in turn bankrupted 747 Savings and Loans, many of whom were operating more or less as banks, thus requiring the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to cover their debts and losses with tax payer money. This with some other "deregulation" policies, ultimately led to the largest political and financial scandal in U.S. history to that date, the savings and loan crisis. The ultimate cost of the crisis is estimated to have totaled around $150 billion, about $125 billion of which was directly subsidized by the U.S. government, which further increased the large budget deficits of the early 1990s.

As an indication of this scandal's size, Martin Mayer wrote at the time, "The theft from the taxpayer by the community that fattened on the growth of the savings and loan (S&L) industry in the 1980s is the worst public scandal in American history. Teapot Dome in the Harding administration and the Credit Mobilier in the times of Ulysses S. Grant have been taken as the ultimate horror stories of capitalist democracy gone to seed. Measuring by money, [or] by the misallocation of national resources... the S&L outrage makes Teapot Dome and Credit Mobilier seem minor episodes."[102]

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith called it "the largest and costliest venture in public misfeasance, malfeasance and larceny of all time".[103]

Age and health concerns

As Reagan was, at the time, the oldest person to be inaugurated as president (age 69), and also the oldest person to hold the office (age 77), his health became a concern at times during his presidency. Former White House correspondent Lesley Stahl later wrote that she and other reporters noticed what might have been early symptoms of Reagan's later Alzheimer's disease.[104] She said that on her last day on the beat, Reagan spoke to her for a few moments and did not seem to know who she was, before then returning to his normal self.[104] However, Reagan's primary physician, Dr. John Hutton, said the president "absolutely" did not "show any signs of dementia or Alzheimer's".[105] His doctors noted that he began exhibiting Alzheimer's symptoms only after he left the White House.[106]

On July 13, 1985, Reagan underwent surgery to remove polyps from his colon, causing the first-ever invocation of the Acting President clause of the 25th Amendment. On January 5, 1987, Reagan underwent surgery for prostate cancer which caused further worries about his health, but which significantly raised the public awareness of this "silent killer".

Elections

1984 election

Reagan's opponent in the 1984 presidential election was former Vice President Walter Mondale, who had been Carter's running mate in 1980. With questions about Reagan's age, and a weak performance in the first presidential debate, his ability to perform the duties of president for another term was questioned. His apparent confused and forgetful behavior was evident to his supporters; they had previously known him clever and witty. Rumors began to circulate that he had Alzheimer's disease.[107][108] Reagan rebounded in the second debate, and confronted questions about his age, quipping, "I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent's youth and inexperience," which generated applause and laughter, even from Mondale himself.[109]

That November, Reagan was re-elected, winning 49 of 50 states.[110] The president's overwhelming victory saw Mondale carry only his home state of Minnesota with a razor-thin margin and the District of Columbia. Reagan won a record 525 electoral votes, the most of any candidate in United States history,[111] and received 59% of the popular vote to Mondale's 41%.[110]

1988 election and transition

In the 1988 presidential election, Vice President George H. W. Bush defeated Democratic Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts, taking 53.4% of the popular vote and 426 of the 538 electoral votes. The Bush administration would include several veterans of the Reagan administration, including James Baker and Attorney General Dick Thornburgh. On January 11, 1989, Reagan addressed the nation for the last time on television from the Oval Office, nine days before handing over the presidency to Bush. On the morning of January 20, 1989, Ronald and Nancy Reagan met with the Bushes for coffee at the White House before escorting them to the Capitol Building, where Bush took the oath of office.

Evaluation and legacy

Since Reagan left office in 1989, substantial debate has occurred among scholars, historians, and the general public surrounding his legacy.[112] Supporters have pointed to a more efficient and prosperous economy as a result of Reagan's economic policies,[113] foreign policy triumphs including a peaceful end to the Cold War,[114] and a restoration of American pride and morale.[115] Proponents also argue Reagan restored faith in the American Dream with his unabated and passionate love for the United States,[116] after a decline in American confidence and self-respect under Jimmy Carter's perceived weak leadership, particularly during the Iran hostage crisis, as well as his gloomy, dreary outlook for the future of the United States during the 1980 election.[117] Critics contend that Reagan's economic policies resulted in rising budget deficits,[118] a wider gap in wealth, and an increase in homelessness[119] and that the Iran–Contra affair lowered American credibility.[120]

Despite the continuing debate surrounding his legacy, many conservative and liberal scholars agree that Reagan has been the most influential president since Franklin D. Roosevelt, leaving his imprint on American politics, diplomacy, culture, and economics through his effective communication, dedicated patriotism and pragmatic compromising.[121] Since he left office, historians have reached a consensus,[122] as summarized by British historian M. J. Heale, who finds that scholars now concur that Reagan rehabilitated conservatism, turned the nation to the right, practiced a considerably pragmatic conservatism that balanced ideology and the constraints of politics, revived faith in the presidency and in American exceptionalism, and contributed to victory in the Cold War.[123]

See also

- United States presidential election, 1976

- United States presidential election, 1980

- United States presidential election, 1984

- History of the United States (1980–91)

- Premiership of Margaret Thatcher

- Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Simi Valley, California

- 600-ship Navy

Footnotes

- ↑ "A Look Back At The Polls". CBS News. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ↑ Weisberg, pp. 56-57

- ↑ Weisberg, pp. 61-63

- ↑ Uchitelle, Louis (September 22, 1988). "Bush, Like Reagan in 1980, Seeks Tax Cuts to Stimulate the Economy". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ↑ Hakim, Danny (March 14, 2006). "Challengers to Clinton Discuss Plans and Answer Questions". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ↑ Kneeland, Douglas E. (August 4, 1980) "Reagan Campaigns at Mississippi Fair; Nominee Tells Crowd of 10,000 He Is Backing States' Rights." The New York Times. p. A11. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ↑ John David Lees, Michael Turner. Reagan's first four years: a new beginning? Manchester University Press ND, 1988. p. 11

- 1 2 3 4 5 "U.S. Senate: Supreme Court Nominations: 1789-Present". www.senate.gov. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Biskupic, Joan (September 4, 2005). "Rehnquist left Supreme Court with conservative legacy". USA Today. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ↑ Weisberg, pp. 116-117

- ↑ Weisberg, pp. 68-69

- ↑ Murray, Robert K. and Blessing, Tim H. 1993. Greatness in the White House. Penn State Press. p. 80

- ↑ Karaagac, John (2000). Ronald Reagan and Conservative Reformism. Lexington Books. p. 113. ISBN 0-7391-0296-6.

- ↑ Cannon (2001) p. 99

- ↑ Hayward, pp. 146–148

- ↑ Peter B. Levy (1996). Encyclopedia of the Reagan-Bush Years. ABC-CLIO. pp. 305–306.

- ↑ Mitchell, Daniel J. (July 19, 1996). "The Historical Lessons of Lower Tax Rates". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on May 30, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2007.

- ↑ "Bruce Bartlett on Tax Increases & Reagan on NRO Financial". Old.nationalreview.com. October 29, 2003. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ↑ Bartlett, Bruce (February 27, 2009). "Higher Taxes: Will The Republicans Cry Wolf Again?". Forbes. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ↑ Brownlee, Elliot; Graham, Hugh Davis (2003). The Reagan Presidency: Pragmatic Conservatism & Its Legacies. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press. pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Steuerle, C. Eugene (1992). The Tax Decade: How Taxes Came to Dominate the Public Agenda. Washington D.C.: The Urban Institute Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-87766-523-0.

- ↑ Tempalski (2006), Table 2

- ↑ "Historical Budget Data". Congressional Budget Office. March 20, 2009. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Federal Budget Receipts and Outlays". Presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ↑ "Annual Statistical Supplement, 2008 – Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Trust Funds (4.A)" (PDF). Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- 1 2 Rosenbaum, David E (January 8, 1986). "Reagan insists Budget Cuts are way to Reduce Deficit". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan: Presidency, Domestic Policies". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Views from the Former Administrators". EPA Journal. Environmental Protection Agency. November 1985. Archived from the original on July 15, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ↑ "The Reagan Presidency". Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ↑ Pear, Robert (April 19, 1992). "U.S. to Reconsider Denial of Benefits to Many Disabled". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- ↑ Weisberg, pp. 75-76

- ↑ Weisberg, p. 78

- ↑ Cline, Seth (1 March 2013). "What Happened Last Time We Had a Budget Sequester?". US News and World Report. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ Graham, Otis (January 27, 2003). "Ronald Reagan's Big Mistake". The American Conservative. Archived from the original on July 29, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- 1 2 Reagan, Ronald. (November 6, 1986) Statement on Signing the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. Collected Speeches, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- ↑ "The War on Drugs". pbs. org. May 10, 2001. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ "NIDA InfoFacts: High School and Youth Trends". National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ Randall, Vernellia R (April 18, 2006). "The Drug War as Race War". The University of Dayton School of Law. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Interview: Dr. Herbert Kleber". PBS. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

The politics of the Reagan years and the Bush years probably made it somewhat harder to get treatment expanded, but at the same time, it probably had a good effect in terms of decreasing initiation and use. For example, marijuana went from thirty-three percent of high-school seniors in 1980 to twelve percent in 1991.

- 1 2 Bachman, Gerald G.; et al. "The Decline of Substance Use in Young Adulthood". The Regents of the University of Michigan. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Thirty Years of America's Drug War". PBS. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ "The Reagan-Era Drug War Legacy". stopthedrugwar.org. June 11, 2004. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Reagan Doctrine". United States State Department.

- ↑ McAleavy, Tony. Modern World History.

- ↑ Reagan, Ronald. (June 8, 1982). "Ronald Reagan Address to British Parliament". The History Place. Retrieved April 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Towards an International History of the War in Afghanistan, 1979–89". The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 2002. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- ↑ "LGM-118A Peacekeeper". Federation of American Scientists. August 15, 2000. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ↑ "Großdemo gegen Nato-Doppelbeschluss, SPIEGEL on the mass protests against deployment of nuclear weapons in West Germany".

- ↑ "Reagan and Thatcher, political soul mates". MSNBC. Associated Press. June 5, 2004. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ Robert C. Rowland, and John M. Jones. Reagan at Westminster: Foreshadowing the End of the Cold War (Texas A&M University Press; 2010)

- ↑ "Addresses to both Houses of Parliament since 1939," Parliamentary Information List, Standard Note: SN/PC/4092, Last updated: November 12, 2014, Author: Department of Information Services

- ↑ "Former President Reagan Dies at 93". Los Angeles Times. June 6, 2004. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ↑ Cannon (1991), pp. 314–317.

- 1 2 "1983: Korean Airlines flight shot down by Soviet Union". A&E Television. Archived from the original on March 3, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ↑ Pace (1995). "GPS History, Chronology, and Budgets". The Global Positioning System (PDF). Rand. p. 248.

- ↑ Pellerin, United States Updates Global Positioning System Technology: New GPS satellite ushers in a range of future improvements

- 1 2 3 "Deploy or Perish: SDI and Domestic Politics". Scholarship Editions. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ↑ Adelman, Ken (July 8, 2003). "SDI:The Next Generation". Fox News Channel. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ↑ Beschloss, p. 293

- ↑ Beschloss, p. 294

- ↑ Thomas, Rhys (Writer/Producer) (2005). The Presidents (Documentary). A&E Television.

- ↑ Hamm, Manfred R. (June 23, 1983). "New Evidence of Moscow's Military Threat". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- ↑ Lebow, Richard Ned & Stein, Janice Gross (February 1994). "Reagan and the Russians". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Gaidar, Yegor (2007). Collapse of an Empire: Lessons for Modern Russia (in Russian). Brookings Institution Press. pp. 190–205. ISBN 5-8243-0759-8.

- ↑ Gaidar, Yegor. "Public Expectations and Trust towards the Government: Post-Revolution Stabilization and its Discontents". Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ↑ Stein, Sam (April 7, 2010). "Giuliani's Obama-Nuke Critique Defies And Ignores Reagan". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- 1 2 Lettow, Paul (July 20, 2006). "President Reagan's Legacy and U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on April 11, 2010.

- 1 2 "Hyvästi, ydinpommi". Helsingin Sanomat. September 5, 2010. pp. D1–D2.

- ↑ "Toward The Summit; Previous Reagan-Gorbachev Summits". The New York Times. May 29, 1988. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Modern History Sourcebook: Ronald Reagan: Evil Empire Speech, June 8, 1982". Fordham University. May 1998. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- 1 2 Keller, Bill (March 2, 1987). "Gorbachev Offer 2: Other Arms Hints". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ↑ "INF Treaty". US State Department. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- ↑ Talbott, Strobe (August 5, 1991). "The Summit Goodfellas". Time. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ↑ Reagan (1990), p. 713

- ↑ Reagan (1990), p. 720

- ↑ "1989: Malta summit ends Cold War". BBC News. December 3, 1984. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- ↑ Stephen S. Rosenfeld (Spring 1986). "The Reagan Doctrine: The Guns of July". Foreign Affairs. 64 (4). Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ↑ Crile, George (2003). Charlie Wilson's War: The Extraordinary Story of the Largest Covert Operation in History. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-854-9.

- ↑ Pach, Chester (2006). "The Reagan Doctrine: Principle, Pragmatism, and Policy". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 36 (1): 75–88. JSTOR 27552748. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2006.00288.x.

- ↑ Coll, Steve (July 19, 1992). "Anatomy of a Victory: CIA's Covert Afghan War". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ↑ Harnden, Toby (September 26, 2001). "Taliban still have Reagan's Stingers". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ↑ Harrison, Selig S. "A Chinese Civil War." The National Interest, February 7, 2011.

- ↑ Magnuson, Ed (21 November 1983). "Getting Back to Normal". Time.

- ↑ Steven F. Hayward. The Age of Reagan: The Conservative Counterrevolution: 1980–1989. Crown Forum. ISBN 1-4000-5357-9.

- ↑ "United Nations General Assembly resolution 38/7, page 19". United Nations. 2 November 1983.

- ↑ Archived July 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Smith, William E. (1985-09-16). "South Africa Reagan's Abrupt Reversal". TIME. Retrieved 2014-04-14.

- ↑ https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=ZZopAAAAIBAJ&sjid=AYQDAAAAIBAJ&dq=anti-apartheid%20act%20reagan&pg=4676%2C4983327

- ↑ https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=iOJLAAAAIBAJ&sjid=uIsDAAAAIBAJ&dq=bush%20sanctions%20south%20africa%201989&pg=4903%2C1578476

- ↑ "Libya: Fury in the Isolation Ward". Time. August 23, 1982. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- 1 2 "Operation El Dorado Canyon". GlobalSecurity.org. April 25, 2005. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "1986:US Launches air-strike on Libya". BBC News. April 15, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ "A/RES/41/38 November 20, 1986". United Nations. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ↑ "Travels of President Ronald Reagan". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian.

- ↑ "Remembering the Assassination Attempt on Ronald Reagan". CNN. 2001-03-30. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ↑ D'Souza, Dinesh (June 8, 2004). "Purpose". National Review. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ↑ Langer, Gary (June 7, 2004). "Reagan's Ratings: ‘Great Communicator's’ Appeal Is Greater in Retrospect". ABC. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ Weisberg, pp. 128-129

- ↑ Weisberg, pp. 129-134

- ↑ Brinkley, A. (2009). American History: A Survey Vol. II, p. 887, New York: McGraw-Hill

- ↑ Timothy Curry and Lynn Shibut, The Cost of the Savings and Loan Crisis: Truth and Consequences FDIC, December 2000.

- ↑ The Greatest-Ever Bank Robbery: The Collapse of the Savings and Loan Industry by Martin Mayer (Scribner's)

- ↑ John Kenneth Galbraith, The Culture of Contentment. Houghton Mifflin, 1992.

- 1 2 Rouse, Robert (March 15, 2006). "Happy Anniversary to the first scheduled presidential press conference - 93 years young!". American Chronicle.

- ↑ Altman, Lawrence K (October 5, 1997). "Reagan's Twilight – A special report; A President Fades into a World Apart". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ Altman, Lawrence K., M.D. (June 15, 2004). "The Doctors World; A Recollection of Early Questions About Reagan's Health". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ "The Debate: Mondale vs. Reagan". National Review. October 4, 2004. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- ↑ "Reaction to first Mondale/Reagan debate". PBS. October 8, 1984. Archived from the original on February 18, 2001. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ "1984 Presidential Debates". CNN. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- 1 2 "1984 Presidential Election Results". David Leip. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- ↑ "The Reagan Presidency". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Andrew L. Johns, ed., A Companion to Ronald Reagan (Wiley-Blackwell, 2015).

- ↑ Hayward, pp. 635–638

- ↑ Beschloss, p. 324

- ↑ Cannon (1991, 2000), p. 746

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan restored faith in America". Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ↑ Lipset, Seymour Martin; Schneider, William. "The Decline of Confidence in American Institutions" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ↑ Cannon (2001), p. 128

- ↑ Dreier, Peter (April 3, 2011). "Don't add Reagan's Face to Mount Rushmore". The Nation.

- ↑ Gilman, Larry. "Iran-Contra Affair". Advameg. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- ↑ "American President". Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ↑ Henry, David (December 2009). "Ronald Reagan and the 1980s: Perceptions, Policies, Legacies. Ed. by Cheryl Hudson and Gareth Davies. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. xiv, 268 pp. $84.95, ISBN 978-0-230-60302-8.)". The Journal of American History. 96 (3): 933–934. JSTOR 25622627. doi:10.1093/jahist/96.3.933.

- ↑ Heale, M.J. in Cheryl Hudson and Gareth Davies, eds. Ronald Reagan and the 1980s: Perceptions, Policies, Legacies (2008) Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 0-230-60302-5 p. 250

References

- Appleby, Joyce; Alan Brinkley; James M. McPherson (2003). The American Journey. Woodland Hills, California: Glencoe/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-824129-4.

- Beschloss, Michael (2007). Presidential Courage: Brave Leaders and How They Changed America 1789–1989. Simon & Schuster.

- Cannon, Lou (2000). President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 1-891620-91-6.

- Cannon, Lou; Michael Beschloss (2001). Ronald Reagan: The Presidential Portfolio: A History Illustrated from the Collection of the Ronald Reagan Library and Museum. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-891620-84-3.

- Coleman, Bradley Lynn and Kyle Longley, eds. Reagan and the World: Leadership and National Security, 1981–1989 (University Press of Kentucky, 2017), 319 pp. essays by scholars

- Diggins, John Patrick (2007). Ronald Reagan: Fate, Freedom, and the Making of History. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Freidel, Frank; Hugh Sidey (1995). The Presidents of the United States of America. Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association. ISBN 0-912308-57-5.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (2005). The Cold War: A New History. The Penguin Press.

- Hertsgaard, Mark. (1988) On Bended Knee: The Press and the Reagan Presidency. New York, New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux.

- LaFeber, Walter (2002). America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1971. New York: Wiley.

- Matlock, Jack (2004). Reagan and Gorbachev: How the Cold War Ended. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-46323-2.

- Morris, Edmund (1999). Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan. Random House. includes fictional material

- Reagan, Nancy (1989). My Turn: The Memoirs of Nancy Reagan. New York: Harper Collins.

- Reagan, Ronald (1990). An American Life. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7434-0025-9.

- Reeves, Richard (2005). President Reagan: The Triumph of Imagination. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-3022-1.

- Regan, Donald (1988). For the Record: From Wall Street to Washington. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-163966-3.

- Service, Robert. The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991 (2015) excerpt

- Walsh, Kenneth (1997). Ronald Reagan. New York: Random House Value Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-517-20078-3.

- Weisberg, Jacob (2016). Ronald Reagan. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-9728-3.

Further reading

External links

- Reagan Library

- Ronald Reagan biography on whitehouse.gov

- Reagan Era study guide, timeline, quotes, trivia, teacher resources

| U.S. Presidential Administrations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Carter |

Reagan Presidency 1981–1989 |

Succeeded by G. H. W. Bush |