|

The translation of "bucke uerteþ" is uncertain. Some translate the former word as "buck-goat" and the latter as "turns" or "cavorts," but the current critical consensus is that the line is the stag or goat "farts" (Millett 2003c; Wulstan 2000, 8).

Christian version in Latin

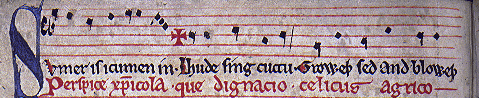

Beneath the Middle English lyrics in the manuscript (British Library MS Harley 978, f. 11v), there is also a set of Latin lyrics which consider the sacrifice of the Crucifixion of Jesus:

Latin

- Perspice Christicola†

- que dignacio

- Celicus agricola

- pro vitis vicio

- Filio non parcens

- exposuit mortis exicio

- Qui captivos semiuiuos a supplicio

- Vite donat et secum coronat

- in celi solio

†written "χρ̅icola" in the manuscript (see Christogram).

|

Modern English

- Observe, Christian,

- such honour!

- The heavenly farmer,

- owing to a defect in the vine,

- not sparing the Son,

- exposed him to the destruction of death.

- To the captives half-dead from torment,

- He gives them life and crowns them with himself

- on the throne of heaven.

|

Renditions and recordings

Studio albums

- The English Singers made the first studio recording in New York, ca. 1927, released on a 10-inch 78rpm disc, Roycroft Living Tone Record No.159, in early 1928 (Taylor 1929, 12; Hoffmann 2004; Haskell 1988, 115–16).

- A second recording, made by the Winchester Music Club, followed in 1929. Released on Columbia (England) D40119 (matrix number WAX4245-2), this twelve-inch 78rpm record was made to illustrate the second in a series of five lectures by Sir George Dyson, for the International Educational Society, and is titled Lecture 61. The Progress Of Music. No. 1 Rota (Canon): Summer Is A Coming In (Part 4) (Leslie 1942; Siese n.d.).

- For similar purposes, E. H. Fellowes conducted the St. George's Singers in a recording issued ca. 1930 on Columbia (US) 5715, a ten-inch 78rpm disc, part of the eight-disc album M-221, the Columbia History of Music by Ear and Eye, Volume One, Period 1: To the Opening of the Seventeenth Century (Leslie 1942; Hall 1948, 578).

- The London Madrigal Group, conducted by T.B. Lawrence, recorded the work on 10 January 1936. This recording was issued later that year on Victrola 4316 (matrix numbers OEA2911 and OEA2913), a ten-inch 78rpm disc (Hall 1948, 578).

- Cardiacs side project Mr and Mrs Smith and Mr Drake recorded an arrangement of the song on their self-titled album in 1984 (Mr Spencer 2011).

- Richard Thompson's own arrangement is the earliest song on his album 1000 Years of Popular Music (2003 Beeswing Records) (Deusner 2009).[lower-alpha 1]

- Emilia Dalby and the Sarum Voices covered the song for the album Emilia (2009 Signum Classics) (Hyperion Records n.d.).

- Post-punk band The Futureheads perform the song a cappella for their album Rant (2012 Nul Records) (McAlpine 2012).

Film

The rendition sung in the climax of the 1973 British film The Wicker Man (Minard 2009) is a mixed translation by Anthony Shaffer (Anon. n.d.):

Sumer is Icumen in,

Loudly sing, cuckoo!

Grows the seed and blows the mead,

And springs the wood anew;

Sing, cuckoo!

Ewe bleats harshly after lamb,

Cows after calves make moo;

Bullock stamps and deer champs,

Now shrilly sing, cuckoo!

Cuckoo, cuckoo

Wild bird are you;

Be never still, cuckoo!

Television

In the childrens' television programme Bagpuss, the mice sing a song called "The Mouse Organ Song: We Will Fix It", to a tune adapted from "Sumer Is Icumen In" (Rogers 2010).

Parodies

This piece was parodied as "Ancient Music" by the American poet Ezra Pound (Lustra, 1916):

Winter is icumen in,

Lhude sing Goddamm,

Raineth drop and staineth slop,

And how the wind doth ramm!

Sing: Goddamm.

Skiddeth bus and sloppeth us,

An ague hath my ham.

Freezeth river, turneth liver,

Damm you; Sing: Goddamm.

Goddamm, Goddamm, 'tis why I am, Goddamm,

So 'gainst the winter's balm.

Sing goddamm, damm, sing goddamm,

Sing goddamm, sing goddamm, DAMM.

The song is also parodied by "P. D. Q. Bach" (Peter Schickele) as "Summer is a cumin seed" for the penultimate movement of his Grand Oratorio The Seasonings.

The song is also referenced in "Carpe Diem," by The Fugs on their 1965 debut album, The Fugs First Album.

Carpe diem,

Sing, cuckoo sing,

Death is a-comin in,

Sing, cuckoo sing.

death is a-comin in.

Another parody is Plumber is icumen in by A.Y. Campbell :

Plumber is icumen in;

Bludie big tu-du.

Bloweth lampe, and showeth dampe,

And dripth the wud thru.

Bludie hel, boo-hoo!

Thawth drain, and runneth bath;

Saw sawth, and scruth scru;

Bull-kuk squirteth, leake spurteth;

Wurry springeth up anew,

Boo-hoo, boo-hoo.

Tom Pugh, Tom Pugh, well plumbes thu, Tom Pugh;

Better job I naver nu.

Therefore will I cease boo-hoo,

Woorie not, but cry pooh-pooh,

Murie sing pooh-pooh, pooh-pooh,

Pooh-pooh!

See also

Notes

- ↑ "1000 Years of Popular Music kicks off with 'Summer Is Icumen In', which is the original summer anthem and could be heard blasting from many a tavern and castle during the balmy middle months of 1260."

References

- Albright, Daniel (2004), Modernism and Music: An Anthology of Sources, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-01267-0

- Anon. (n.d.). "Sumer Is Icumen In: An Old English Folk Song – Sheet Music, Midi and Mp3". MFiles. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- British Library MS Harley 978, f. 11v. "Sumer Is Icumen In". MS Harley 978, f. 11v.

- Compazine (2013). "The Cuckoo Song (Sumer Is Icumen In)". YouTube. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Crystal, David (2004), Stories of English, New York: Overlook Press

- Deusner, Stephen M. (17 July 2006). "Richard Thompson 1,000 Years of Popular Music". Pitchfork. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Hall, David (1948). The Record Book: A Guide to the World of the Phonograph. New York: Oliver Durrell, Inc.

- Haskell, Harry (1988). The Early Music Revival: A History. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

- Hoffmann, Frank (2004). “Roycroft (Label)", Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781135949495.

- Hyperion Records (n.d.). "Miri it is – Sumer is icumen in". Hyperion SIGCD141. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Leslie, George Clark, supervising editor (1942). "Fornsete, John (c. 1226): 'Sumer is icumen in' (The Reading Rota)". The Gramophone Shop Encyclopedia of Recorded Music, new edition, completely revised. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc.

- McAlpine, Fraser (2012). "The Futureheads Rant Review". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Millett, Bella (2003a). "Sumer Is Icumen In: London, British Library, MS Harley 978, f. 11v: Introduction". Wessex Parallel Web Texts website (Accessed 25 November 2014).

- Millett, Bella (2003b). "Sumer Is Icumen In: London, British Library, MS Harley 978, f. 11v: Text". Wessex Parallel Web Texts website (Accessed 25 November 2014).

- Millett, Bella (2003c). "Sumer Is Icumen In: London, British Library, MS Harley 978, f. 11v: Notes". Wessex Parallel Web Texts website (Accessed 25 November 2014).

- Millett, Bella (2003d). "Sumer Is Icumen In: London, British Library, MS Harley 978, f. 11v: Translations". Wessex Parallel Web Texts website (Accessed 25 November 2014).

- Millett, Bella (2004). "Sumer Is Icumen In: London, British Library, MS Harley 978, f. 11v: The Manuscript". Wessex Parallel Web Texts website (Accessed 25 November 2014).

- Minard, Jenny (2009). "Sumer Is Icumen In at Abbey Ruins". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Rogers, Jude. 2010. "Papa’s Got a Brand New Bagpuss: How Sandra Kerr’s Folk Roots for the Fondly Remembered 1970s Children’s TV Show Has Influenced Today’s Performers". The Guardian (Thursday 29 July).

- Roscow, G. H. (1999). "What is 'Sumer is icumen in'?" Review of English Studies 50, no. 198:188–95.

- Siese, Ray (n.d.). "Dyson Trust Discography".

- Mr Spencer (2011). "Ex-Cardiacs Tunesmith William D. Drake Writes Songs That Are Timeless, Bold and Beautiful". Louder Than War. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Spicer, Paul (n.d.). "Britten, Benjamin: Spring Symphony op. 44 (1949) 45' for soprano, alto and tenor soloists, chorus, boys' choir, and orchestra". Boosey & Hawkes. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Taylor, Deems (1929). “Hear the English Singers", The World’s Work 58:p. 12

- Wulstan, David. (2000). "'Sumer Is Icumen In': A Perpetual Puzzle-Canon?". Plainsong and Medieval Music 9, no. 1 (April): 1–17.

Further reading

- Bukofzer, Manfred F. (1944) "'Sumer is icumen in': A Revision". University of California Publications in Music 2: 79–114.

- Colton, Lisa (2014). "Sumer Is Icumen In". Grove Music Online (1 July, revision) (accessed 26 November 2014)

- Duffin, Ross W. (1988) "The Sumer Canon: A New Revision". Speculum 63:1–21.

- Falck, Robert. (1972). "Rondellus, Canon, and Related Types before 1300". Journal of the American Musicological Society 25, no. 1 (Spring): 38-57.

- Fischer, Andreas (1994). "'Sumer is icumen in': The Seasons of the Year in Middle English and Early Modern English". In Studies in Early Modern English, edited by Dieter Kastovsky, 79–95. Berlin and New York: Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-014127-2.

- Greentree, Rosemary (2001). The Middle English Lyric and Short Poem. Annotated Bibliographies of Old and Middle English Literature 7. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-621-9.

- Sanders, Ernest H. (2001). "Sumer Is Icumen In". Grove Music Online (20 January, bibliography updated 28 August 2002) (accessed 26 November 2014).

- Schofield, B. (1948). "The Provenance and Date of 'Sumer is icumen in'". The Music Review 9:81–86.

- Taylor, Andrew, and A. E. Coates (1998). "The Dates of the Reading Calendar and the Summer Canon". Notes and Queries 243:22–24.

- Toguchi, Kōsaku. (1978). "'Sumer is icumen in' et la caccia: Autour du problème des relations entre le 'Summer canon' et la caccia arsnovistique du trecento". In La musica al tempo del Boccaccio e i suoi rapporti con la letteratura, edited by Agostino Ziino, 435–46. L'ars nova italiana del Trecento 4. Certaldo: Centro di Studi sull'Ars Nova Italiana del Trecento.

External links

|

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

| |

_(mid_13th_C)%2C_f.11v_-_BL_Harley_MS_978.jpg)