Maryam Jinnah

| Rattanbai Petit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Rattanbai Petit 20 February 1900 Bombay, British India |

| Died |

20 February 1929 (aged 29) Bombay, British India |

| Spouse(s) |

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (m. 1918–1929; her death) |

| Children | 1 (Dina Jinnah) |

| Family |

Petit–Tata family (by birth) Jinnah family (by marriage) |

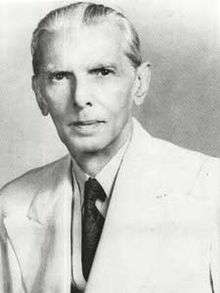

Rattanbai "Ruttie" Petit, (born Rattanbai Petit; 20 February 1900 – 20 February 1929), also known by her married name Rattanbai Jinnah,[1][2][3] was the second wife of Muhammad Ali Jinnah — an important figure in the creation of Pakistan.

Rattanbai was the only daughter of Sir Dinshaw Petit, who in turn, was the son of Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, a member of the Petit family and the founder of the first cotton mills in India. Her mother, Sylla Petit, was the daughter of Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata and sister of JRD Tata, one of the shareholders of Tata Sons and a part of the Tata family.

Family and background

Ruttie was born on 20 February 1900 in Bombay, British India. She was the daughter and the only child of the Parsi parents, Sir Dinshaw Petit and Sylla Tata. Her father was the second baronet of Petit. Her paternal grandfather, Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, was the first baronet of Petit, and the founder of the first cotton mills in India. While, her maternal grandfather, Ratanji Dadabhoy Tata, and uncle, J. R. D. Tata, were the shareholders of the Tata Sons, as well as the chairpersons of the Tata Group, one of the leading business companies of India. Her maternal grandmother, Suzanne Brière, was the first woman in India to drive a car.[4]

Marriage and problems

In 1918, at the age of 18, Ruttie married Muhammad Ali Jinnah, despite the opposition of her family and the Parsi community. She converted to Islam before marriage, adopting the name, Maryam Jinnah, though she never used it,[3][5] and cut all the ties with her family. Upon marriage, the couple resided at South Court Mansion, Bombay, but also made frequent trips to Europe.

Ruttie and Jinnah made a head-turning couple. She used to call her husband “J”. Her long hair would be decked in fresh flowers, and she wore vibrant silk and headbands lavish with diamonds, rubies and emeralds. According to most sources, the couple could not have been happier in those early years of their marriage. Sir Dinshaw mourned Ruttie socially even after his granddaughter Dina Jinnah, their only child, was born on 15 August 1919.[6]

By mid-1922, Jinnah was facing political isolation as he devoted every spare moment to be the voice of separatist incitement in a nation torn by Hindu-Muslim antipathy. His increasingly late hours and the ever-increasing distance between them left Ruttie isolated.[7]

Last days and death

After Ruttie's death from cancer, it appeared that Jinnah missed her a great deal. G Allana in "Quaid-i-Azam Jinnah: The Story of a Nation" based on the narrative of a chauffeur of Mr Jinnah writes:

"You know servants in household come to know everything that is going around them. Sometimes more than twelve years after Begum Jinnah's (Mrs. Jinnah) death, the boss would order at dead of night a huge ancient wooden chest to be opened, in which were stored clothes of his dead wife and his married daughter. He would intently look into those clothes, as they were taken out of box and were spread on the carpets. He would gaze at them for long with eloquent silence. Then his eyes turn moisten..."[8]

Relationship with Jinnah

Ruttie's complex relationship with her husband can also be elaborated by reading some extracts of her last letter to him "...When one has been as near to the reality of Life (which after all is Death) as I have been dearest, one only remembers the beautiful and tender moments and all the rest becomes a half veiled mist of unrealities. Try and remember me beloved as the flower you plucked and not the flower you tread upon." ... ".. Darling I love you – I love you – and had I loved you just a little less I might have remained with you – only after one has created a very beautiful blossom one does not drag it through the mire. The higher you set your ideal the lower it falls. I have loved you my darling as it is given to few men to be loved. I only beseech you that the tragedy which commenced in love should also end with it...".[9]

Jinnah is seen as a very private person and he hardly showed emotions but he is known to have cried twice in public. One of the occasions was the funeral of his beloved wife Ruttie in 1929 and the other one in August 1947, when he visited her grave one last time before leaving for Pakistan. Jinnah left India in August 1947, never to return again.[10]

References

- ↑ Hamdani, Yasser (22 May 2017). "Who is Maryam Jinnah". dailytimes.com.pk. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ↑ Zakaria, Rafia (7 December 2012). "Love, Marriage and Mrs. Jinnah". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- 1 2 InpaperMagazine, From (3 March 2012). "First lady: The Flower of Bombay". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ "Icons of Indian Industry". Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ Newspaper, From the (21 December 2012). "Maryam Jinnah". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ↑ Ruttie Jinnah's Letters

- ↑ Ruttie Jinnah – Story of Pakistan

- ↑ Ganje Firishte pp 9, 1955, Saadat Hassan Manto

- ↑ The life of Ruttie Jinnah in pictures

- ↑ A look at the life of Ruttie's last letter to her husband Jinnah

Bibliography

- Chagla, M. C. (1961), Individual and the State, Asia Publishing House.

- Reddy, Sheela (2017), Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage that Shook India, Penguin India.

- Wolpert, Stanley (1984), Jinnah of Pakistan, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-614-21694-X