Ran (film)

| Ran | |

|---|---|

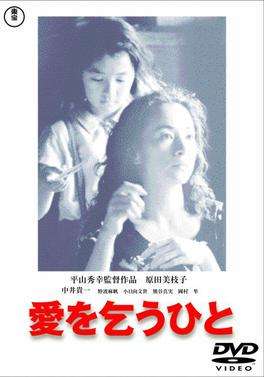

Theatrical release poster | |

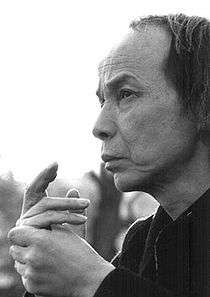

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Toru Takemitsu |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by | Akira Kurosawa |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 162 minutes |

| Country | |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | $11 million[2] |

| Box office | $12 million (Japan)[2] |

Ran (乱, Japanese for "chaos") is a 1985 period tragedy directed, edited and co-written by Akira Kurosawa as an adaptation of Shakespeare's tragedy King Lear. It is a Japanese-French venture produced by Herald Ace, Nippon Herald Films and Greenwich Film Productions. The film stars Tatsuya Nakadai as Hidetora Ichimonji, an aging Sengoku-era warlord who decides to abdicate as ruler in favor of his three sons. The film is an adaptation of the Shakespearean tragedy King Lear, and includes segments based on legends of the daimyō Mōri Motonari.

Production planning of Ran went through a long period of preparation. Kurosawa first conceived of the idea that would become Ran in the mid-1970s, when he read about the Sengoku-era warlord Mōri Motonari. Motonari was famous for having three highly loyal sons. Kurosawa then began seriously considering the theme of reversing the loyalty of the sons in a revised plot where the sons of a new film would be antagonists of their father. Although the film became heavily inspired by Shakespeare's play King Lear, Kurosawa only began using it after he had started pre-planning for Ran. Following this pre-planning, Kurosawa then filmed Dersu Uzala in 1975 followed by Kagemusha in the early 1980s before returning to film Ran after securing financial backing.

Ran was Kurosawa's last epic, and has often been cited as amongst his finest achievements. With a budget of $11 million, it was the most expensive Japanese film ever produced up to that time. Ran was previewed on May 31, 1985 at the Tokyo International Film Festival before its release on June 1, 1985 in Japan. The film was hailed for its powerful images and use of color—costume designer Emi Wada won an Academy Award for Costume Design for her work on Ran. The distinctive Gustav Mahler–inspired film score was composed by Toru Takemitsu.

Plot

Act I

Hidetora Ichimonji, a powerful though now elderly warlord, decides to divide his kingdom among his three sons: Taro, Jiro, and Saburo. Taro, the eldest, will receive the prestigious First Castle and become leader of the Ichimonji clan, while Jiro and Saburo will be given the Second and Third Castles. Hidetora is to retain the title of Great Lord and Jiro and Saburo are to support Taro. Saburo, however, points out that Hidetora is foolish if he expects his sons to be loyal to him, reminding him that even Hidetora had previously used the most ruthless methods to attain power. Hidetora infers the comments to be subversive, and when his servant Tango comes to Saburo's defense, he exiles both men. Fujimaki, a visiting warlord who had witnessed these events agrees with Saburo's frankness, and invites him to take his daughter's hand in marriage.

Act II

Following the division of Hidetora's lands between his remaining two sons, Taro's wife Lady Kaede begins to urge her husband to usurp control of the entire Ichimonji clan. When Taro demands Hidetora renounce his title of Great Lord, Hidetora then storms out of the castle and travels to Jiro's castle, only to discover that Jiro is only interested in using Hidetora as a titular pawn. Hidetora and his retinue then leave Jiro's castle as well without any clear destination. Eventually Tango appears with provisions but to no avail. Tango then tells Hidetora of Taro's new decree: death to whoever aids his father. At last Hidetora takes refuge in the Third Castle, abandoned after Saburo's forces followed their lord into exile. Tango does not follow him.

Act III

Shortly thereafter, Hidetora and his samurai retinue are besieged militarily by Taro and Jiro's combined forces. In a short but violent siege, virtually all defenders are slaughtered as the Third Castle is set alight. Solitarily, Hidetora succumbs to madness and wanders away from the burning castle. As Taro and Jiro's forces storm the castle, Taro is killed by a bullet fired by Jiro's general, Kurogane. Hidetora is discovered wandering in the wilderness by Tango who is still loyal to him and who stays to assist Hidetora. In his madness, Hidetora is haunted by horrific visions of the people he destroyed in his quest for power. They take refuge in a peasant's home only to discover that the occupant is Tsurumaru, the brother of Lady Sué, Jiro's wife. Tsurumaru had been blinded and left impoverished after Hidetora took over his land and killed his father, a rival lord.

Act IV

With Taro dead, Jiro becomes the Great Lord of the Ichimonji clan, enabling him to move into the First Castle. Upon Jiro's return from battle, Lady Kaede, who doesn't seem to be fazed by Taro's death, blackmails Jiro into having an affair with her, and she becomes the power behind his throne. Kaede demands that Jiro kill Lady Sué and marry her instead. Jiro orders Kurogane to do the deed, but he refuses, warning Jiro that Kaede means to ruin the entire Ichimonji clan. Kurogane then warns Sué and Tsurumaru to flee. Tango, still watching over Hidetora with Kyoami, encounters two ronin who had once served as spies for Jiro. Before he kills them both, one of the ronin tells him that Jiro is considering sending assassins after Hidetora. Alarmed, Tango rides off to alert Saburo. Hidetora becomes even more insane and runs off into a volcanic plain with a frantic Kyoami in pursuit.

Saburo's army crosses back into Jiro's territory to find him. News also reaches Jiro that two rival lords allied to Saburo (Ayabe and Fujimaki) have also entered the territory, forcing Jiro to hastily mobilize his army. At the field of battle, the two brothers accept a truce, but Saburo becomes alarmed when Kyoami arrives to tell of his father's descent into insanity. Saburo goes with Kyoami to rescue his father and takes 10 warriors with him; Jiro sends several gunners to follow Saburo and ambush them both. Jiro then further orders an attack on Saburo's much smaller force. Saburo's army retreats into the woods for cover and fires on Jiro's forces, frustrating the attack. In the middle of the battle a messenger arrives with news that a rival warlord, Ayabe, is marching on the First Castle, forcing Jiro's army to hastily retreat. Saburo then finds Hidetora in the volcanic plain; Hidetora partially recovers his sanity, and begins repairing his relationship with Saburo. However, one of the snipers Jiro had sent after Saburo's small group shoots and kills Saburo. Overcome with grief, Hidetora dies. Fujimaki and his army arrive to witness Tango and Kyoami lamenting the death of father and son.

Act V

Meanwhile, Tsurumaru and Sué arrive at the ruins of a destroyed castle but inadvertently leave behind the flute that Sué previously gave Tsurumaru when he was banished. She gives a picture of Amida Buddha to him for company while she attempts to retrieve the missing flute. It is when she returns to Tsurumaru's hovel to retrieve it that she is ambushed and killed by Jiro's assassin. At the same time, Ayabe's army pursues Jiro's army to the First Castle and commences a siege. When Kurogane hears that Lady Sué has been murdered by one of Jiro's men, Kurogane confronts Kaede. She admits her perfidy and to her plotting to exact revenge against Hidetora and the Ichimonji clan for having destroyed her family years before. Enraged, Kurogane finally snaps and decapitates Kaede. Jiro, Kurogane, and all Jiro's men subsequently die in the battle with Ayabe's army that follows.

A solemn funeral procession is held for Saburo and Hidetora. Meanwhile, left alone in the castle ruins, Tsurumaru accidentally drops, and loses, the Amida Buddha image Sué had given to him. The film ends with a distance shot of Tsurumaru, alone, silhouetted, atop the ruins.

Cast

- Tatsuya Nakadai as Great Lord Hidetora Ichimonji: The main character of the film. This character is the equivalent of Shakespeare's King Lear.

- Akira Terao as Lord Taro: Hidetora's oldest of three sons and heir to Hidetora's power. This character is analogous to Goneril.

- Jinpachi Nezu as Lord Jiro: Hidetora's middle son, who is only a year younger than Taro. This character is analogous to Regan.

- Daisuke Ryu as Lord Saburo: Hidetora's youngest son. This character is analogous to Cordelia.

- Masayuki Yui as Tango: Hidetora's main advisor. This character is analogous to Kent.

- Shinnosuke "Peter" Ikehata as Kyoami: Hidetora's comic fool.

- Mieko Harada as Lady Kaede: Taro's wife, Hidetora's daughter-in-law and Jiro and Saburo's sister-in-law. She seduces Jiro and becomes an insidious influence to his actions comparable to Edmund's role as adapted from King Lear.

| Character | Equivalent in King Lear | Actor |

|---|---|---|

| Hidetora Ichimonji | King Lear | Tatsuya Nakadai |

| Taro | Goneril | Akira Terao |

| Jiro | Regan | Jinpachi Nezu |

| Saburo | Cordelia | Daisuke Ryu |

| Tango | Kent | Masayuki Yui |

| Kyoami | Fool | Shinnosuke "Peter" Ikehata |

| Tsurumaru | Gloucester | Takeshi Nomura |

| Lady Sué | Edgar | Yoshiko Miyazaki |

| Lady Kaede | Edmund | Mieko Harada |

| Kurogane | Albany | Hisashi Igawa |

| Nobuhiro Fujimaki | King of France | Hitoshi Ueki |

Production

Ran was Kurosawa's last epic film and by far his most expensive. At the time, its budget of $11 million made it the most expensive Japanese film in history leading to its distribution in 1985.[3][4] It is a Japanese-French venture[1] produced by Herald Ace, Nippon Herald Films and Greenwich Film Productions. Filming of Ran started in 1983.[5] The 1,400 uniforms and suits of armor used for the extras were designed by costume designer Emi Wada and Kurosawa, and were handmade by master tailors over more than two years. The film also used 200 horses. Kurosawa loved filming in lush and expansive locations, and most of Ran was shot amidst the mountains and plains of Mount Aso, Japan's largest active volcano. Kurosawa was also granted permission to shoot at two of the country's most famous landmarks, the ancient castles at Kumamoto and Himeji. For the castle of Lady Sué's family, he used the ruins of the custom constructed Azusa castle, made by Kurosawa's production crew near Mount Fuji.[6][7][8] Hidetora's third castle, which was burned to the ground, was actually a real building which Kurosawa built on the slopes of Mount Fuji. No miniatures were used for that segment, and Tatsuya Nakadai had to do the scene where Hidetora flees the castle in one take.[6] Apparently, Kurosawa also wanted to include a scene that required an entire field to be sprayed gold; it was filmed but Kurosawa cut it out of the final film during editing. The documentary A.K. shows the filming of the scene.

Kurosawa would often shoot a scene with three cameras simultaneously, each using different lenses and angles. Many long-shots were employed throughout the film and very few close-ups. On several occasions he used static cameras and suddenly brought the action into frame, rather than using the camera to track the action. He also used jump cuts to progress certain scenes, changing the pace of the action for filmic effect.[9]

Akira Kurosawa's wife of 39 years, Yōko Yaguchi, died during the production of this film. He halted filming for one day to mourn before resuming work on the picture. His regular recording engineer Fumio Yanoguchi also died late in production in January 1985.[10]

Development

Kurosawa first conceived of the idea that would become Ran in the mid-1970s, when he read a parable about the Sengoku-era warlord Mōri Motonari. Motonari was famous for having three sons, all incredibly loyal and talented in their own right. Kurosawa began imagining what would have happened had they been bad.[11] Although the film eventually became heavily inspired by Shakespeare's play King Lear, Kurosawa only became aware of the play after he had started pre-planning. According to him, the stories of Mōri Motonari and Lear merged in a way he was never fully able to explain. He wrote the script shortly after filming Dersu Uzala in 1975, and then "let it sleep" for seven years.[6] During this time, he painted storyboards of every shot in the film (later included with the screenplay and available on the Criterion Collection DVD release of the film) and then continued searching for funding. Following his success with 1980's Kagemusha, which he sometimes called a "dress rehearsal" for Ran, Kurosawa was finally able to secure backing from French producer Serge Silberman.

Kurosawa once said "Hidetora is me," and there is evidence in the film that Hidetora serves as a stand-in for Kurosawa.[12] Roger Ebert agrees, arguing that Ran "may be as much about Kurosawa's life as Shakespeare's play."[13] Ran was the final film of Kurosawa's "third period" (1965–1985), a time where he had difficulty securing support for his pictures, and was frequently forced to seek foreign financial backing. While he had directed over twenty films in the first two decades of his career, he directed just four in these two decades. After directing Red Beard (1965), Kurosawa discovered that he was considered old-fashioned and did not work again for almost five years. He also found himself competing against television, which had reduced Japanese film audiences from a high of 1.1 billion in 1958 to under 200 million by 1975. In 1968 he was fired from the 20th Century Fox epic Tora! Tora! Tora! over what he described as creative differences, but others said was a perfectionism that bordered on insanity. Kurosawa tried to start an independent production group with three other directors, but his 1970 film Dodesukaden was a box-office flop and bankrupted the company.[14] Many of his younger rivals boasted that he was finished. A year later, unable to secure any domestic funding and plagued by ill-health, Kurosawa attempted suicide by slashing his wrists. Though he survived, his misfortune would continue to plague him until the late 1980s.

Kurosawa was influenced by the William Shakespeare play King Lear and borrowed elements from it. Both depict an aging warlord who decides to divide up his kingdom among his offspring. Hidetora has three sons—Taro, Jiro, and Saburo who correspond to Lear's daughters Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia. In both, the warlord foolishly banishes anyone who disagrees with him as a matter of pride—in Lear it is the Earl of Kent and Cordelia; in Ran it is Tango and Saburo. The conflict in both is that two of the lord's children ultimately turn against him, while the third supports him, though Hidetora's sons are far more ruthless than Goneril and Regan. Both King Lear and Ran end with the death of the entire family, including the lord.

However, there are some crucial differences between the two. King Lear is a play about undeserved suffering, and Lear himself is at his worst a fool. Hidetora, by contrast, has been a cruel warrior for most of his life: a man who ruthlessly murdered men, women, and children to achieve his goals.[15] In Ran, Lady Kaede, Lady Sué, and Tsurumaru were all victims of Hidetora. Whereas in King Lear the character of Gloucester had his eyes gouged out by Lear's enemies, in Ran it was Hidetora himself who gave the order to blind Tsurumaru. The role of the Fool has been expanded into a major character (Kyoami), and Lady Kaede serves as the equivalent of Goneril, but is given a more complex and important character.[9] Kurosawa was concerned that Shakespeare gave his characters no past, and he wanted to give King Lear a history.[16]

The complex and variant etiology for the word Ran used as the title has been variously translated as "chaos", "rebellion", or "revolt"; or to mean "disturbed" or "confused".

Filming

The filming of Ran began in 1983.[5] The development and conception of the filming of the war scenes in the film were influenced by Kurasawa's opinions on nuclear warfare. According to Michael Wilmington, Kurosawa told him that much of the film was a metaphor for nuclear warfare and the anxiety of the post-Hiroshima age.[17] He believed that, despite all of the technological progress of the 20th century, all people had learned was how to kill each other more efficiently.[18] In Ran, the vehicle for apocalyptic destruction is the arquebus, an early firearm that was introduced to Japan in the 16th century. Arquebuses revolutionized samurai warfare, and the age of swords and single-combat warriors fell rapidly by the wayside. Now, samurai warfare would be characterized by massive faceless armies engaging each other at a distance. Kurosawa had already dealt with this theme in his previous film Kagemusha, in which the Takeda cavalry is destroyed by the arquebuses of the Oda and Tokugawa clans.

In Ran, the battle of Hachiman Field is a perfect illustration of this new kind of warfare. Saburo's arquebusiers annihilate Jiro's cavalry and drive off his infantry by engaging them from the woods, where the cavalry are unable to venture. Similarly, Saburo's assassination by a sniper also shows how individual heroes can be easily disposed of on a modern battlefield. Kurosawa also illustrates this new warfare with his camera. Instead of focusing on the warring armies, he frequently sets the focal plane beyond the action, so that in the film they appear as abstract entities.[19]

Casting

The description of Hidetora in the first script was originally based on Toshiro Mifune.[16] However, the role was cast to Tatsuya Nakadai, an actor who had played several supporting and major characters in previous Kurosawa films, as well as Shingen and his "kagemusha", "double", in Kagemusha. Other Kurosawa veterans in Ran were Masayuki Yui (Tango), Jinpachi Nezu (Jiro) and Daisuke Ryu (Saburo), all of whom were in Kagemusha. Others had not, but would go on to work with Kurosawa again, such as Akira Terao (Taro) and Mieko Harada (Lady Kaede) in Dreams. Hisashi Igawa (Kurogane) would be in Rhapsody in August, and later, in Dreams, where Yui would also appear. Kurosawa also hired two comedians for lighter moments: Shinnosuke "Peter" Ikehata as Hidetora's fool Kyoami and Hitoshi Ueki as rival warlord Nobuhiro Fujimaki. Kurosawa hired approximately 1,400 extras.

Acting style

While most of the characters in Ran are portrayed by conventional acting techniques, two performances are reminiscent of Japanese Noh theater. The heavy, ghost-like makeup worn by Tatsuya Nakadai's character, Hidetora, resembles the emotive masks worn by traditional Noh performers. The body language exhibited by the same character is also typical of Noh theater: long periods of static motion and silence, followed by an abrupt, sometimes violent, change in stance. The character of Lady Kaede is also Noh-influenced. The Noh treatment emphasizes the ruthless, passionate, and single-minded natures of these two characters.

Music

Craig Lysy writing for Movie Music UK commented on the strengths of the composer for Kurosawa's purposes for composing the soundtrack used in the film: "Tôru Takemitsu was Japan’s preeminent film score composer and Kurosawa secured his involvement in 1976, during the project’s early stages. Their initial conception of the score was to use tategoe, a 'shrill-voice' chant style without instrumentation. Over the intervening years Kurosawa’s conception of the score changed dramatically. As they began production his desire had changed 180 degrees, now insisting on a powerful Mahleresque orchestral score. Takemitsu responded with what many describe as his most romantic effort, one that achieved a perfect blending of Oriental and Occidental sensibilities."[20][21]

Takemitsu has stated that he was significantly influenced by the Japanese karmic concept of Ma interpreted as a surplus of energy surrounding an abundant void. As Lysy stated: "Takemitsu was guided in his efforts best summed up in the Japanese word Ma, which suggests the incongruity of a void abounding with energy. He related: 'My music is like a garden, and I am the gardener. Listening to my music can be compared with walking through a garden and experiencing the changes in light, pattern and texture.'"[21]

The project was the second of two which allowed Kurasawa and Takemitsu to collaborate during their lifetimes, the first being Dodes'ka-den. Lysy summarized the second project stating: "It should be noted that the collaboration between Kurosawa and the temperamental Takemitsu was rocky. Kurosawa constantly sent Takemitsu notes, which only served to infuriate him, so he frequently visited the set to gain a direct sensual experience. Takemitsu actually resigned and demanded to be stripped from the credits after an intense fight over the scoring of scene 36, where Kurosawa bypassed him and had the sound technician alter the register and time meter of his music. Fortunately producer Masato Hara intervened, made peace, and Takemitsu returned to the film. Years later Takemitsu would relate: 'Overall, I still have this feeling of … "Oh, if only he’d left more up to me …" But seeing it now … I guess it’s fine the way it is.'"[21]

Kurosawa originally had wanted the London Symphony Orchestra to perform the score for Ran, however, upon meeting conductor Hiroyuki Iwaki of the Sapporo Symphony Orchestra, he engaged Iwaki and the orchestra to record the score.[22] Kurosawa made the orchestra play up to 40 takes of the music.[22] The running time of the soundtrack is 73 minutes 09 seconds which was re-released in 2016 after its original release in 1985 by Silva Screen productions. It was produced under release number SILCD-1518 by Reynold da Silva and David Stoner.[21]

Themes

_castle_massacre.jpg)

The analogy of the development of Ran to Shakespeare's King Lear extends also to the thematic elements as they are found in the film. As with King Lear, the central theme of the film is its thematic study of the inheritance of power intergenerationally between a single parent and his three children. John F. Danby argues by analogy that Lear dramatizes, among other things, the contrasting meanings of "Nature".[23] In Ran, the thematic study in cinematography and content of "nature" and the "natural" are revisited numerous times from the starting scene depicting expansive clouds to the closing scene depicting a sole figure filmed against an expansive landscape. The "unnatural", or the word "Ran" translated as chaos or the "disordered", occurs in the thematically recurrent scenes of warfare and nihilism depicted throughout the film. In analogy to Shakespeare, Kurosawa reflects a debate in Shakespeare's time about what human nature and nature really were like. There are thematically two strongly contrasting views of human nature in Kurasawa's film: that of Hidetora's party (analogous to Lear, Gloucester, Albany, Kent), and that of his older sons who come to rule (analogous to Edmund, Cornwall, Goneril, and Regan).

As with Shakespeare, Kurosawa's film thematically explores these two aspects of human nature. Lady Kaeda and her husband are the new inheriting generation, members of an age of competition, suspicion, glory, in contrast with the older society which has come down from Hidetora and his times, with its belief in co-operation, reasonable decency, and respect for the whole as greater than the part. Ran, like King Lear, is thus an allegory. The older society, that of the medieval vision, with its doting king and warlord, falls into error, and is threatened by the new inheriting generation; it is partially regenerated and saved by a vision of a new order, embodied in Hidetora's rejected youngest son, which ultimately fails.[23]

The three themes of chaos, nihilism, and warfare recur throughout the film. With reference to chaos, in many scenes Kurosawa foreshadows it by filming approaching cumulonimbus clouds, which finally break into a raging storm during the castle massacre. Hidetora is an autocrat whose powerful presence keeps the countryside unified and at peace. His abdication frees up other characters, such as Jiro and Lady Kaede, to pursue their own agendas, which they do with absolute ruthlessness. While the title is almost certainly an allusion to Hidetora's decision to abdicate (and the resulting mayhem that follows), there are other examples of the disorder of life, what Michael Sragow calls a "trickle-down theory of anarchy."[24] The death of Taro ultimately elevates Lady Kaede to power and turns Jiro into an unwilling pawn in her schemes. Saburo's decision to rescue Hidetora ultimately draws in two rival warlords and leads to an unwanted battle between Jiro and Saburo, culminating in the destruction of the Ichimonji clan.

The ultimate example of chaos is the absence of gods. When Hidetora sees Lady Sué, a devout Buddhist and the most religious character in the film, he tells her, "Buddha is gone from this miserable world." Sué, despite her belief in love and forgiveness, eventually has her head cut off. When Kyoami claims that the gods either do not exist or are the cause of human suffering, Tango responds, "[The gods] can't save us from ourselves." Kurosawa has repeated the point, saying "humanity must face life without relying on God or Buddha."[11] The last shot of the film shows Tsurumaru standing on top of the ruins of his family castle. Unable to see, he stumbles towards the edge until he almost falls over. He drops the scroll of the Buddha his sister had given him and just stands there, "a blind man at the edge of a precipice, bereft of his god, in a darkening world."[25] This may symbolize the modern concept of the death of God, as Kurosawa also claimed "Man is perfectly alone... [Tsurumaru] represents modern humanity."[6]

In addition to its chaotic elements, Ran also contains a strong element of nihilism, which is present from the opening sequence, where Hidetora mercilessly hunts down a boar only to refrain from eating it, to the last scene with Tsurumaru. Roger Ebert describes Ran as "a 20th-century film set in medieval times, in which an old man can arrive at the end of his life having won all his battles, and foolishly think he still has the power to settle things for a new generation. But life hurries ahead without any respect for historical continuity; his children have their own lusts and furies. His will is irrelevant, and they will divide his spoils like dogs tearing at a carcass."[13]

This marked a radical departure from Kurosawa's earlier films, many of which balanced pessimism with hopefulness. Only Throne of Blood, an adaptation of Shakespeare's Macbeth, had as bleak an outlook. Even Kagemusha, though it chronicled the fall of the Takeda clan and their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Nagashino, had ended on a note of regret rather than despair. By contrast, the world of Ran is a Hobbesian world, where life is an endless cycle of suffering and everybody is a villain or a victim, and in many cases both. Heroes like Saburo may do the right thing, but in the end they are doomed as well. Unlike other Kurosawa heroes, like Kikuchiyo in Seven Samurai or Watanabe from Ikiru, who die performing great acts, Saburo dies pointlessly. Gentle characters like Lady Sué are doomed to fall victim to the evil and violence around them, and conniving characters like Jiro or Lady Kaede are never given a chance to atone and are predestined to a life of wickedness culminating in violent death.[26]

Reception

Though Ran was critically acclaimed upon its premiere[27] on June 1, 1985 in Japan, it was only modestly successful financially, earning only ¥2,510,000,000 ($12 million), just enough to break even.[28] Its U.S. release six months later earned another $2–3 million, and a re-release in 2000 accumulated $337,112.[29]

Critical reviews

According to review aggregators Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic[30] the film is recognized as receiving universal acclaim. Shawn Levy writing for the Portland Oregonian wrote that, "In many respects, it's Kurosawa's most sumptuous film, a feast of color, motion and sound: Considering that its brethren include Kagemusha, The Seven Samurai and Dersu Uzala, the achievement is extraordinary."[31] Writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert stated, "Ran is a great, glorious achievement."[32] In the San Francisco Examiner, G. Allen Johnson stated: "Kurosawa pulled out all the stops with Ran, his obsession with loyalty and his love of expressionistic film techniques allowed to roam freely."[33]

Writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, Bob Graham stated: "In Ran, the horrors of life are transformed by art into beauty. It is finally so moving that the only appropriate response is silence."[34] Gene Siskel writing for the Chicago Tribune wrote: "The physical scale of Ran is overwhelming. It's almost as if Kurosawa is saying to all the cassette buyers of America, in a play on Clint Eastwood`s phrase, 'Go ahead, ruin your night'--wait to see my film on a small screen and cheat yourself out of what a movie can be."[35] Vincent Canby writing for The New York Times stated: "Though big in physical scope and of a beauty that suggests a kind of drunken, barbaric lyricism, Ran has the terrible logic and clarity of a morality tale seen in tight close-up, of a myth that, while being utterly specific and particular in its time and place, remains ageless, infinitely adaptable."[36]

Roger Ebert awarded the film four out of four stars, with extended commentary, "Kurosawa (while directing Ran) often must have associated himself with the old lord as he tried to put this film together, but in the end he has triumphed, and the image I have of him, at 75, is of three arrows bundled together."[37] In 2000, it was inducted into Ebert's Great Movies list.

Michal Sragow writing for Salon in 2000 summarized the Shakespearean origins of the play: "Kurosawa’s Lear is a 16th century warlord who has three sons and a career studded with conquests. Kurosawa’s genius is to tell his story so that every step suggests how wild and savage a journey it has been. At the start, this bold, dominating figure, now called Hidetora, is a sacred monster who wants to be a sort of warlord emeritus. He hopes to bequeath power to his oldest son while retaining his own entourage and emblems of command. He hasn’t reckoned with the ambition of his successor or the manipulative skill of his heir’s wife, who goes for the sexual and political jugular of anyone who invades her sphere."[24]

Accolades

Ran was also nominated for Academy Awards for art direction, cinematography, costume design (which it won), and Kurosawa's direction. It was also successfully nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film. In Japan, Ran was conspicuously not nominated for "Best Picture" at the Awards of the Japanese Academy. However, it won two prizes, for best art direction and best music score, and received four other nominations, for best cinematography, best lighting, best sound and best supporting actor (Hitoshi Ueki, who played Saburo's patron, Lord Fujimaki). Ran also won two awards from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, for best foreign-language film and best make-up artist, and was nominated for best cinematography, best costume design, best production design, and best screenplay—adapted. Despite its limited commercial success at the time of its release, the film's accolades have improved greatly, and it is now regarded as one of Kurosawa's masterpieces.[13]

Ran also won Best Director and Best Foreign Film awards from the National Board of Review, a Best Film award and a Best Cinematography award (Takao Saitô, Shôji Ueda, and Asakazu Nakai) from the National Society of Film Critics, a Best Foreign Language Film award from the New York Film Critics Circle, a Best Music award (Tôru Takemitsu) and a Best Foreign Film award from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, a Best Film award and a Best Cinematography award from the Boston Society of Film Critics, a Best Foreign Feature award from the Amanda Awards from Norway, a Blue Ribbon Award for Best Film, a Best European Film award from the Bodil Awards, a Best Foreign Director award from the David di Donatello Awards, a Joseph Plateau Award for Best Artistic Contribution, a Director of the Year award and a Foreign Language Film of the Year award from the London Critics Circle Film Awards, a Best Film, a Best Supporting Actor (Hisashi Igawa) and a Best Director from the Mainichi Film Concours, and an OCIC award from the San Sebastian Film Festival.[38][39]

Ran was completed too late to be entered at Cannes and had its premiere at Japan's first Tokyo International Film Festival.[40] Kurosawa skipped the film's premiere, angering many in the Japanese film industry. As a result, Ran was not submitted as Japan's entry for the Best Foreign Language Film category of the Oscars. Serge Silberman subsequently tried to get it nominated as a French co-production but failed. However, American director Sidney Lumet helped organize a successful campaign to have Kurosawa nominated as Best Director.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Ran (1985)". British Film Institute. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- 1 2 "Ran". Toho Kingdom. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ Hagopian, Kevin. "New York State Writers Institute Film Notes - Ran". Archived from the original on 2007-03-12. Retrieved 2017-06-08.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (1986-06-22). "Film View: 'Ran' Weathers the Seasons". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Galbraith 2002, pp. 569–576

- 1 2 3 4 Kiyoshi Watanabe (October 1985). "Interview with Akira Kurosawa on Ran". Positif. 296.

- ↑ MTV News, "Happy 444th Birthday, William Shakespeare, Screenwriter", Mark Bourne, 04/22/2008, .

- ↑ Soundtrack of Ran. Azusa Castle listed as individual track on soundtrack release .

- 1 2 Kurosawa's RAN. Jim's Reviews.

- ↑ Kurosawa 2008, p. 128.

- 1 2 Peary, Gerald (July 1986). "Akira Kurosawa". Boston Herald.

- ↑ "Ran". Flicks kicks off with a Lear-inspired epic. Retrieved 2017-06-09.

- 1 2 3 Ebert, Roger. "Ran (1985)." Roger Ebert's Great Movies, October 1, 2000.

- ↑ Prince 1999, p. 5

- ↑ Prince 1999, p. 287

- 1 2 3 "Ask the Experts Q&A". Great Performances. Kurosawa. Retrieved 2017-06-13.

- ↑ Wilmington, Michael (December 19, 2005). "Apocalypse Song". Criterion Collection.

- ↑ Bock, Audie (1981-10-04). "Kurosawa on His Innovative Cinema". New York Times. p. 21.

- ↑ Prince, Stephen (Commentary) (2005). Ran (Film). North America: Criterion Collection.

- ↑ Music for the Movies: Toru Takemitsu (DVD). Sony Classical Essential Classics. 1995.

- 1 2 3 4 Lysy, Craig. "Movie Music UK". Retrieved 2017-06-08.

- 1 2 巨匠が認めた札響の力. Yomiuri Shimbun (in Japanese). July 1, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- 1 2 Danby, John. Shakespeare's Doctrine of Nature–A Study of King Lear.

- 1 2 Sragow, Michael (September 21, 2000). "Lear meets the energy vampire". Salon.com.

- ↑ Prince 1999, p. 290

- ↑ Prince 1999, pp. 287–289

- ↑ Lupton 2005, p. 165.

- ↑ "Ran". tohokingdom.com. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ↑ "Movie Ran". 2006-02-20. Archived from the original on 2006-02-20.

- ↑ Metacritic (2017-06-11). "Aggregator review of Ran". Metacritic.

- ↑ Shawn Levy, Review of Ran, Portland Oregonian, 1 Dec 2000, p.26.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (1985-12-25). "Film View: 'Ran'". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ G. Allen Johnson. Review of Ran, San Francisco Examiner.

- ↑ Graham, Bob (2000-09-29). "Film Review: 'Ran'". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Siskel, Gene (1985-12-25). "Film Review: 'Ran'". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (1986-06-22). "Film Review: 'Ran' Weathers the Seasons". The New York Times.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (1985-12-25). "Film Review: 'Ran'". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ "Ran". Awards and Nomnations. 1985-06-01.

- ↑ Newman, Nick (2016-01-06). "Kurosawa’s ‘Ran’ and Chaplin’s ‘The Great Dictator’ Get Restored In New Trailers". The Film Stage.

- ↑ "Tokyo Festival Opens With a Kurosawa Film". Associated Press. 1985-06-01.

Bibliography

- Galbraith, Stuart, IV (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber and Faber, Inc. ISBN 0-571-19982-8.

- Kurosawa, Akira (2008). Akira Kurosawa: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1578069971.

- Lupton, Catherine (2005). Chris Marker: Memories of the Future. Reaktion Books. p. 165. ISBN 1861892233 – via Google Books.

towering critical success of Ran, [...] welcomed as a magisterial return to form

- Prince, Stephen (1999). The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (2nd, revised ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01046-3.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ran (film) |

- Ran on IMDb

- Ran at AllMovie

- Ran (in Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database

- Ran Script — Dialogue Transcript: A transcript of film from Drew's Script-O-Rama.

- Ran at Rotten Tomatoes