Ralambo

| King of Imerina | |

|---|---|

| Reign | c. 1575–1612 |

| Predecessor | Andriamanelo |

| Successor | Andrianjaka |

| Born | Alasora |

| Died |

c. 1612 Ambohidrabiby |

| Burial | Ambohidrabiby |

| Spouse |

Rafotsitohina Ratsitohinina Rafotsiramarohavina Rafotsindrindra |

| Issue | Twelve sons (Andriantompokoindrindra, Andrianjaka, Andrianimpito, Andrianpanarivomanga, Andriantompobe, Rafidy, Andriamasoandro, Andriampontany, Andrianakotrina, Andriamanforalambo, Andriantsinompo, Andriampolofantsy) and three daughters (Ravololondralambo, Ravoamasina, unknown) |

| Dynasty | Hova dynasty |

| Father | Andriamanelo |

| Mother | Randapavola |

Ralambo was the ruler of the Kingdom of Imerina in the central Highlands region of Madagascar from 1575 to 1612. Ruling from Ambohidrabiby, Ralambo expanded the realm of his father, Andriamanelo, and was the first to assign the name of Imerina to the region. Oral history has preserved numerous legends about this king, including several dramatic military victories, contributing to his heroic and near-mythical status among the kings of ancient Imerina. The circumstances surrounding his birth, which occurred on the highly auspicious date of the first of the year, are said to be supernatural in nature and further add to the mystique of this sovereign.

Oral history attributes numerous significant and lasting political and cultural innovations to King Ralambo. He is credited with popularizing the consumption of beef in the Kingdom of Imerina and celebrating this discovery with the establishment of the fandroana New Year's festival which traditionally took place on the day of Ralambo's birth. According to legend, circumcision and polygamy were also introduced under his rule, as was the division of the noble class (andriana) into four sub-castes. Oral history furthermore traces the tradition of royal idols (sampy) in Imerina to the reign of Ralambo, who made heavy use of these supernatural objects to expand his realm and consolidate the divine nature of his sovereignty. Due to the enduring cultural legacy left by this king, Ralambo is often considered a key figure in the development of Merina cultural identity.

Early life

Born in the sacred highland village of Alasora to King Andriamanelo and Queen Randapavola, Ralambo was the only one of his parents' children to survive to adulthood. According to one legend, as a child he may have been known by the name Rabiby, being given the name Ralambo after successfully killing a particularly ferocious wild boar (lambo) in the woods.[1] Another story attributes his name to a wild boar that walked past the threshold of the house where his mother was resting shortly after giving birth to him. However, both of these explanations are likely to have originated at some point after his reign; it is more probable that he took the name Ralambo after propagating the consumption of the meat of the zebu, called lambo in the proto-Malagasy language and the Malayo-Polynesian tongue from which it derived.[2]

A popular legend imbues the birth of Ralambo with a mystical character. The legend relates that his mother, who was known in her youth as Ramaitsoanala ("Green Forest"), was the daughter of the Vazimba water goddess Ivorombe ("Great Bird"). With the assistance of her celestial mother, Ramaitsoanala confronted and overcame numerous obstacles. After her marriage to Andriamanelo (whereupon she assumed the name Queen Randapavola), one of these obstacles took the form of reproductive difficulties: six consecutive times Randapavola miscarried or lost her children in infancy. When she was pregnant with her seventh child, the queen was especially afraid for her unborn child because the number seven was traditionally associated with death. This time, Randapavola sought the guidance of an astrologer to protect the unborn child from an evil fate. On his advice she chose to defy the tradition of delivering the baby at her parents' home village of Ambohidrabiby, rather choosing the village of Alasora, to the north of Antananarivo, because this cardinal direction embodied great power. According to the tale, the queen gave birth in a house built to resemble a boat (called a kisambosambo) evocative of the transoceanic origins of the Malagasy people. There, Randapavola took the name Rasolobe upon delivering a healthy son, Ralambo, on the first day of the first month of the year (Alahamady), the most auspicious date for the birth of a sovereign.[2]

Reign

Ralambo's many enduring and significant political and cultural achievements of his reign have earned him a heroic and near mythical status among the greatest ancient sovereigns of Merina history.[3][4] Ralambo was the first to assign the name of Imerina ("Land of the Merina people") to the central highland territories where he ruled.[5] He moved his capital from Alasora to Ambohidrabiby, location of the former capital of his maternal grandfather King Rabiby.[3] The first sub-divisions of the andriana noble caste were created when Ralambo split it into four ranks.[6] He introduced the traditions of circumcision and family intermarriage (such as between parent and step-child, or between half-siblings) among Merina nobles, these practices having already existed among certain other Malagasy ethnic groups. The practice of sanctifying deceased Merina sovereigns is also believed to have originated with this king.[7]

Ralambo is credited with introducing the tradition of polygamy in Imerina.[7] The Merina legend of the origin of this practice was recorded in the 19th-century collection of Merina andriana oral history and genealogy entitled Tantara ny Andriana eto Madagasikara. According to this source, Ralambo had already married once when his servant encountered the beautiful princess Rafotsimarobavina and four female companions gathering edible greens in a valley west of Ambohidrabiby. Upon hearing of her beauty, Ralambo instructed the servant to make her a marriage offer on his behalf. The servant asked three times, and each time the princess refused to give her consent, instead replying "If Ralambo is king and I am queen." The fourth time, after Ralambo had instructed his servant to carry her to him by force, the princess agreed to marry on the condition that it be done properly with the consent of her parents, a condition to which the king agreed. Ralambo then informed his first wife of his intention to marry again, to which she replied, "I approve your decision," and the marriage was made.[8] Ralambo ultimately took four wives in total: Rafotsitohina, Rafotsiramarobavina, Ratsitohinina and Rafotsindrindra. These marriages produced three daughters and twelve sons, the eldest of whom, Andriantompokoindrindra, was passed over for Ralambo's succession in favor of his second son, Andrianjaka.[3]

Ralambo expanded and defended his realm through a combination of diplomacy and successful military action aided by the procurement of the first firearms in Imerina by way of trade with kingdoms on the coast. According to legend, when a group of warriors from a village near the Ikopa river attempted to attack the village of Ambohibaoladina, Ralambo so frightened the warriors with the noise of a single shotgun blast that every warrior ran into the Ikopa river and drowned.[8] Imposing a capitation tax for the first time (the vadin-aina, or "price of secure life"), he was able to establish the first standing Merina royal army[9] and established units of blacksmiths and silversmiths to equip them.[7] He famously repelled an attempted invasion by an army of the powerful western coastal Betsimisaraka people at a site now known as Mandamako ("Lazy") at Androkaroka, north of Alasora. The Betsimisaraka traditionally only fought at night and so were found asleep in their camp by Ralambo and his men and were easily vanquished.[9] In another famous incident, Ralambo's army set a trap for a Vazimba king named Andrianafovaratra who claimed to control thunder. Ralambo's emissary, a man named Andriamandritany, was sent to the Vazimba king to invite him to participate in a contest of superiority against Ralambo. While Andrianafovaratra traveled to join Ralambo for the competition, Andriamandritany set fire to the Vazimba capital of Imerinkasinina. The Vazimba king saw the smoke and began to hasten back to the village but was captured in an ambush laid by Ralambo's troops and was forced to exile himself in the forests far to the east.[8]

Fandroana

According to oral history, the wild zebu cattle that roamed the Highlands were first domesticated for food in Imerina under the reign of Ralambo. Different legends attribute the discovery that zebu were edible to the king's servant[10] or to Ralambo himself.[6] Ralambo disseminated this discovery throughout his realm, as well as the practice and design of cattle pen construction.[11] Ralambo is likewise credited with founding the traditional ceremony of the fandroana (the "Royal Bath"),[7] although others have suggested he merely added certain practices to the celebration of a long-standing ritual.[2] Among the Merina, legend characterizes the fandroana as a festival established by Ralambo to celebrate his culinary discovery.[12]

According to one version of the story, while traversing the countryside, Radama and his men came across a wild zebu so exceptionally fat that the king decided to make a burnt offering of it. As the zebu flesh cooked, the enticing smell led Ralambo to taste the meat. He declared zebu meat to be fit for human consumption. In honor of the discovery, he decided to establish a holiday called fandroana that would be distinguished by the consumption of well-fattened zebu meat. The holiday was to be celebrated on the day of his birth, which coincided with the first day of the year. To this end, the holiday symbolically represented a community-wide renewal that would take place over a period of several days before and after the first of the year.[13]

Although the precise form of the original holiday cannot be known with certainty and its traditions have evolved over time, 18th- and 19th-century accounts provide insight into the festival as it was practiced at that time.[14] Accounts from these centuries indicate that all family members were required to reunite in their home villages during the festival period. Estranged family members were expected to attempt to reconcile. Homes were cleaned and repaired and new housewares and clothing were purchased. The symbolism of renewal was particularly embodied in the traditional sexual permissiveness encouraged on the eve of the fandroana (characterized by early 19th-century British missionaries as an "orgy") and the following morning's return to rigid social order with the sovereign firmly at the helm of the kingdom.[14] On this morning, the first day of the year, a red rooster was traditionally sacrificed and its blood used to anoint the sovereign and others present at the ceremony. Afterward the sovereign would bathe in sanctified water, then sprinkle it upon attendees to purify and bless them and ensure an auspicious start to the year.[12] Children would celebrate the fandroana by carrying lighted torches and lanterns in a nighttime processional through their villages. The zebu meat eaten over the course of the festival was primarily grilled or consumed as jaka, a preparation reserved uniquely for this holiday. This delicacy was made during the festival by sealing shredded zebu meat with suet in a decorative clay jar. The confit would then be conserved in an underground pit for twelve months to be served at the next year's fandroana.[13]

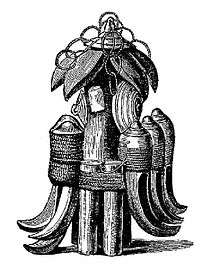

Sampy

Amulets and idols fashioned from assorted natural materials have occupied an important place among many ethnic groups of Madagascar for centuries. Ody, personal amulets believed to protect or allocate powers to the wearer, were commonplace objects possessed by anyone from slave children to kings. The name sampy was given to those amulets that, while physically indistinguishable from ody, were distinct in that their powers extended over an entire community. The sampy were often personified—complete with a distinct personality—and offered their own house with guardians dedicated to their service. Ralambo amassed twelve of the most reputed and powerful sampy from neighboring communities. He furthermore transformed the nature of the relationship between sampy and ruler: whereas previously the sampy had been seen as tools at the disposal of community leaders, under Ralambo they became divine protectors of the leader's sovereignty and the integrity of the state which would be preserved through their power on the condition that the line of sovereigns ensured the sampy were shown the respect due to them. By collecting the twelve greatest sampy—twelve being a sacred number in Merina cosmology—and transforming their nature, Ralambo strengthened the supernatural power and legitimacy of the royal line of Imerina.[15]

The Tantara ny Andriana eto Madagasikara, the 19th-century transcription of Merina oral history, offers an account of the idols' introduction into Imerina. According to legend, one day during Ralambo's reign a woman named Kalobe arrived in Imerina carrying a small object wrapped in banana leaves and grass. She had traveled from her village located at Isondra in Betsileo country to the south which had been destroyed by fire, walking the great distance and traveling only at night in order to deliver to the king what she called Kelimalaza ("the Little Famous One"), giving the impression that it was no less than the greatest treasure in the land. Ralambo took the sampy and built a house for it in a nearby village. He then selected a group of adepts who were to study under Kalobe to learn the mysteries of Kelimalaza. Oral history maintains that Kalobe was "made to disappear" after the adepts' training was completed in order to prevent her from absconding with the precious idol.[8]

Not long after, the legend continues, a group of Sakalava (or, by some accounts, Vazimba) warriors were preparing to attack a village north of Alasora called Ambohipeno. Ralambo announced that it would be sufficient to throw a rotten egg at the warriors, and Kelimalaza would take care of the rest. According to oral history, the egg was thrown and hit a warrior in the head, killing him on contact; his corpse fell onto another warrior and killed him, and this corpse fell onto another and so forth, until the warriors had all been destroyed, forevermore confirming the power of Kelimalaza as the protector of the kingdom in the minds of the Merina populace. Similarly, at the besieged Imerina village of Ambohimanambola, invoking Kelimalaza was said to have produced a massive hailstorm that wiped out the enemy warriors.[8]

The honored place that Ralambo awarded to Kelimalaza encouraged others like Kalobe to bring their own sampy to Ralambo from neighboring lands where they had been introduced long before by the Antaimoro. First after Kelimalaza was Ramahavaly, said to control snakes and repel attacks. The next arrival, Manjakatsiroa, protected the sovereignty of the king from rivals and became the favorite of Ralambo, who kept it always near him. Afterward came Rafantaka, believed to protect against injury and death; others followed, all of Antaimoro origin with the possible exception of Mosasa, which had come from the Tanala forest people to the east.[8] The propagation of similar sampy at the service of less powerful citizens consequently increased throughout Imerina under Ralambo's rule: nearly every village chief, as well as many common families, had one in their possession and claimed the powers and protection their communal sampy offered them.[6] These lesser sampy were destroyed or reduced to the status of ody (personal talismans) by the end of the reign of Ralambo's son, Andrianjaka, officially leaving only twelve truly powerful sampy (known as the sampin'andriana: the "Royal Sampy") which were all in the possession of the king.[6] These royal sampy, including Kelimalaza, continued to be worshiped until their supposed destruction in a bonfire by Queen Ranavalona II upon her public conversion to Christianity in 1869.[16]

Death and succession

Ralambo is believed to have died around 1612. He was buried in the traditional stone tomb of his grandfather, King Rabiby, which still stands at the highland village of Ambohidrabiby.[2] According to a 19th-century source, his death was mourned for a full year. His burial reportedly took place at night and a royal mausoleum (trano masina) was constructed over his tomb, a royal Merina tradition that would continue until the collapse of the 19th century Kingdom of Madagascar.[9] The rules of succession established by Andriamanelo obliged Ralambo to pass over his eldest son (by his second wife) in favor of the succession of Andrianjaka, his younger son by his first wife, Rafotsindrindramanjaka.[3]

References

- ↑ Ellis 1832, pp. 520–538.

- 1 2 3 4 Madatana. "Colline d'Ambohidrabiby" (in French). Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Buyers, Christopher. "The Merina (or Hova) Dynasty: Imerina 2". Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ Bloch 1971, p. 17.

- ↑ Kus 1995, pp. 140–154.

- 1 2 3 4 Raison-Jourde 1983, pp. 141–142.

- 1 2 3 4 Ogot 1992, p. 876.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 de la Vaissière & Abinal 1885, pp. 63–71.

- 1 2 3 Kent 1968, pp. 517–546.

- ↑ Bloch 1985, pp. 631–646.

- ↑ Bloch 1985, pp. 631-646.

- 1 2 de la Vaissière & Abinal 1885, pp. 285–290.

- 1 2 Raison-Jourde 1983, p. 29.

- 1 2 Larson 1999, p. 37–70.

- ↑ Graeber 2007, pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Oliver 1886, p. 118.

Bibliography

- Bloch, Maurice (1971). Placing the dead: tombs, ancestral villages and kinship organization in Madagascar. Berkeley Square, UK: Berkeley Square House. ISBN 978-0-12-809150-0.

- Bloch, Maurice (1985). "Almost Eating the Ancestors". Man. 20 (4): 631–646. JSTOR 2802754.

- Callet, François (1972) [1908]. Tantara ny andriana eto Madagasikara (histoire des rois) (in French). Antananarivo: Imprimerie catholique.

- Ellis, William (1832), "Ellis's History of Madagascar", in Henderson, E., The Monthly Review, III, London

- Graeber, David (2007). Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21915-2.

- Kent, R.K. (1968). "Madagascar and Africa II: The Sakalava, Maroserana, Dady and Tromba before 1700". The Journal of African History. 9 (4): 517–546. doi:10.1017/S0021853700009026.

- Kus, Susan (1995). "Sensuous human activity and the state: towards an archaeology of bread and circuses". In Miller, Daniel; Rowlands, Michael. Domination and Resistance. London: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-12254-2.

- Larson, Pier M. (1999), "A cultural politics of bedchamber construction and progressive dining in Antananarivo: ritual inversions during the fandroana of 1817", in Middleton, Karen, Ancestors, Power and History in Madagascar, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 37–70, ISBN 978-90-04-11289-6

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1992). Africa from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-101711-7.

- Oliver, Samuel (1886). Madagascar: An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Island and its Former Dependencies, Volume 1. New York: Macmillan and Co.

- Raison-Jourde, Françoise (1983). Les souverains de Madagascar (in French). Antananarivo: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-059-7.

- de la Vaissière, Camille; Abinal, Antoine (1885). Vingt ans à Madagascar: colonisation, traditions historiques, moeurs et croyances (in French). Paris: V. Lecoffre.