Train station

.jpg)

A train station, railway station, railroad station, or depot (see below) is a railway facility where trains regularly stop to load or unload passengers or freight.

It generally consists of at least one track-side platform and a station building (depot) providing such ancillary services as ticket sales and waiting rooms. If a station is on a single-track line, it often has a passing loop to facilitate traffic movements. The smallest stations are most often referred to as "stops" or, in some parts of the world, as "halts" (flag stops).

Stations may be at ground level, underground, or elevated. Connections may be available to intersecting rail lines or other transport modes such as buses, trams or other rapid transit systems.

Terminology

In British English, traditional usage favours railway station or simply station, even though train station, which is often perceived as an Americanism, is now about as common as railway station in writing; railroad station is not used, railroad being obsolete there.[1][2][3] In British usage, the word station is commonly understood to mean a railway station unless otherwise qualified.[4]

In the American English, the most common term in contemporary usage is train station. Railway station and railroad station are less frequent.[5]

In addition to its use for storage facilities, in North America the term depot is sometimes used as an alternative name for station, along with the compound forms train depot, railway depot, and railroad depot, but also applicable for goods and other vehicles.[6]

History

The world's first recorded railway station was The Mount on the Oystermouth Railway (later to be known as the Swansea and Mumbles) in Swansea, Wales,[7] which began passenger service in 1807, although the trains were horsedrawn rather than by locomotives.[8]

The two-storey Mount Clare station in Baltimore, Maryland, which survives as a museum, first saw passenger service as the terminus of the horse-drawn Baltimore and Ohio Railroad on 22 May 1830.[9]

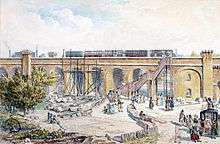

The oldest terminal station in the world was Crown Street railway station in Liverpool, built in 1830, on the locomotive hauled Liverpool to Manchester line. As the first train on the Liverpool-Manchester line left Liverpool, the station is slightly older than the Manchester terminal at Liverpool Road. The station was the first to incorporate a train shed. The station was demolished in 1836 as the Liverpool terminal station moved to Lime Street railway station. Crown Street station was converted to a goods station terminal.

The first stations had little in the way of buildings or amenities. The first stations in the modern sense were on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830.[10] Manchester's Liverpool Road Station, the second oldest terminal station in the world, is preserved as part of the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester. It resembles a row of Georgian houses. Early stations were sometimes built with both passenger and goods facilities, though some railway lines were goods-only or passenger-only, and if a line was dual-purpose there would often be a goods depot apart from the passenger station.[11]

Dual-purpose stations can sometimes still be found today, though in many cases goods facilities are restricted to major stations. In rural and remote communities across Canada and the United States, passengers wanting to board the train had to flag the train down in order for it to stop. Such stations were known as "flag stops" or "flag stations".[12]

Many stations date from the 19th century and reflect the grandiose architecture of the time, lending prestige to the city as well as to railway operations.[13] Countries where railways arrived later may still have such architecture, as later stations often imitated 19th-century styles. Various forms of architecture have been used in the construction of stations, from those boasting grand, intricate, Baroque- or Gothic-style edifices, to plainer utilitarian or modernist styles. Stations in Europe tended to follow British designs and were in some countries, like Italy, financed by British railway companies.[14]

Stations built more recently often have a similar feel to airports, with a simple, abstract style. Examples of modern stations include those on newer high-speed rail networks, such as the Shinkansen in Japan, TGV lines in France and ICE lines in Germany.

Station facilities

Stations usually have staffed ticket sales offices, automated ticket machines, or both, although on some lines tickets are sold on board the trains. Many stations include a shop or convenience store. Larger stations usually have fast-food or restaurant facilities. In some countries, stations may also have a bar or pub. Other station facilities may include: toilets, left-luggage, lost-and-found, departures and arrivals boards, luggage carts, waiting rooms, taxi ranks, bus bays and even car parks. Larger or manned stations tend to have a greater range of facilities including also a station security office. These are usually open for travellers when there is sufficient traffic over a long enough period of time to warrant the cost. In large cities this may mean facilities available around the clock. A basic station might only have platforms, though it may still be distinguished from a halt, a stopping or halting place that may not even have platforms.

In many African and South American countries, and in many places in India, stations are used as a place for public markets and other informal businesses. This is especially true on tourist routes or stations near tourist destinations.

As well as providing services for passengers and loading facilities for goods, stations can sometimes have locomotive and rolling stock depots (usually with facilities for storing and refuelling rolling stock and carrying out minor repair jobs).

Configurations of stations

In addition to the basic configuration of a station, various features set certain types of station apart. The first is the level of the tracks. Stations are often sited where a road crosses the railway: unless the crossing is a level crossing, the road and railway will be at different levels. The platforms will often be raised or lowered relative to the station entrance: the station buildings may be on either level, or both. The other arrangement, where the station entrance and platforms are on the same level, is also common, but is perhaps rarer in urban areas, except when the station is a terminus. Elevated stations are more common, not including metro stations. Stations located at level crossings can be problematic if the train blocks the roadway while it stops, causing road traffic to wait for an extended period of time.

Occasionally, a station serves two or more railway lines at differing levels. This may be due to the station's position at a point where two lines cross (example: Berlin Hauptbahnhof), or may be to provide separate station capacity for two types of service, such as intercity and suburban (examples: Paris-Gare de Lyon and Philadelphia's 30th Street Station), or for two different destinations.

Stations may also be classified according to the layout of the platforms. Apart from single-track lines, the most basic arrangement is a pair of tracks for the two directions; there is then a basic choice of an island platform between, or two separate platforms outside, the tracks. With more tracks, the possibilities expand.

Some stations have unusual platform layouts due to space constraints of the station location, or the alignment of the tracks. Examples include staggered platforms, such as at Tutbury and Hatton railway station on the Derby – Crewe line, and curved platforms, such as Cheadle Hulme railway station on the Macclesfield to Manchester Line. Triangular stations also exist where two lines form a three-way junction and platforms are built on all three sides, for example Shipley and Earlestown stations.

Tracks

In a station, there are different types of tracks to serve different purposes. A station may also have a passing loop with a loop line that comes off the straight main line and merge back to the main line on the other end by railroad switches to allow trains to pass.[15]

A track with a spot at the station to board and disembark trains is called station track or house track[16] regardless of whether it is a main line or loop line. If such track is served by a platform, the track may be called platform track. A loop line without a platform which is used to allow a train to clear the main line at the station only, it is called passing track.[15] A track at the station without a platform which is used for trains to pass the station without stopping is called through track.[16]

There may be other sidings at the station which are lower speed tracks for other purposes. A maintenance track or a maintenance siding, usually connected to a passing track, is used for parking maintenance equipment, trains not in service, autoracks or sleepers. A refuge track is a dead-end siding that is connected to a station track as a temporary storage of a disabled train.[15]

Terminus

A "terminal" or "terminus" is a station at the end of a railway line. Trains arriving there have to end their journeys (terminate) or reverse out of the station. Depending on the layout of the station, this usually permits travellers to reach all the platforms without the need to cross any tracks – the public entrance to the station and the main reception facilities being at the far end of the platforms.

Sometimes, however, the track continues for a short distance beyond the station, and terminating trains continue forwards after depositing their passengers, before either proceeding to sidings or reversing to the station to pick up departing passengers. Bondi Junction and Kristiansand Station, Norway are like this.

Many terminus stations have underground rapid-transit urban rail stations beneath, to transit passengers to the local city or district.

A terminus is frequently, but not always, the final destination of trains arriving at the station. However a number of cities, especially in continental Europe, have a terminus as their main railway stations, and all main lines converge on this station. There may also be a bypass line, used by freight trains that do not need to stop at the main station. In such cases all trains passing through that main station must leave in the reverse direction from that of their arrival. There are several ways in which this can be accomplished:

- arranging for the service to be provided by a multiple-unit or push-pull train, both of which are capable of operating in either direction; the driver simply walks to the other end of the train and takes control from the other cab; this is increasingly the normal method in Europe;

- by detaching the locomotive which brought the train into the station and then either

- using another track to "run it around" to the other end of the train, to which it then re-attaches;

- attaching a second locomotive to the outbound end of the train; or

- by the use of a "wye", a roughly triangular arrangement of track and switches (points) where a train can reverse direction and back into the terminal.

Some termini have a newer set of through platforms underneath (or above, or alongside) the terminal platforms on the main level. They are used by a cross-city extension of the main line, often for commuter trains, while the terminal platforms may serve long-distance services. Examples of underground through lines include the Thameslink platforms at St Pancras in London, the Argyle and North Clyde lines of Glasgow's suburban rail network, the recently built Malmö City Tunnel, in Antwerp in Belgium, the RER at the Gare du Nord in Paris, and many of the numerous S-Bahn lines at terminal stations in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, such as at Zürich Hauptbahnhof.

An American example of a terminal with this feature is Washington, DC's Union Station, where there are bay platforms on the main concourse level to serve terminating trains, and standard island platforms one level below to serve trains continuing southwards. Those tracks run in a tunnel beneath the concourse and emerge a few blocks away to cross the Potomac River into Virginia.

Terminus stations in large cities are by far the biggest stations, with the largest being the Grand Central Terminal in New York City, United States.[17] Often major cities, such as London, Boston, Paris, Istanbul, Tokyo and Milan have more than one terminus, rather than routes straight through the city. Train journeys through such cities often require alternative transport (metro, bus, taxi or ferry) from one terminus to the other. For instance in Istanbul transfers from the Sirkeci Terminal (the European terminus) and the Haydarpaşa Terminal (the Asian terminus) traditionally required crossing the Bosphorus via alternative means, before the railway tunnel linking Europe and Asia was completed. Though some cities, including New York, have both termini and through lines.

Terminals that have competing rail lines using the station frequently set up a jointly owned terminal railroad to own and operate the station and its associated tracks and switching operations.

Junction

A junction is a station where two or more rail routes converge or diverge. It could be a terminus or an en-route station.

Stop

During a journey, the term station stop may be used in announcements, to differentiate a halt during which passengers may alight from a halt for another reason, such as a locomotive change.

A railway stop is a spot along a railway line, usually between stations or at a seldom-used station, where passengers can board and exit the train.

While a junction or interlocking usually divides two or more lines or routes, and thus has remotely or locally operated signals, a station stop does not. A station stop usually does not have any tracks other than the main tracks, and may or may not have switches (points, crossovers).

Halt

A halt, in railway parlance in the Commonwealth of Nations and Republic of Ireland, is a small station, usually unstaffed or with very few staff, and with few or no facilities. In some cases, trains stop only on request, when passengers on the platform indicate that they wish to board, or passengers on the train inform the crew that they wish to alight.

In the United Kingdom, most former halts on the national railway networks have had the word halt removed from their names. Historically, in many instances the spelling "halte" was used, before the spelling "halt" became commonplace. There are only two publicly advertised and publicly accessible National Rail stations with the word "halt" remaining: Coombe Junction and St Keyne Wishing Well.[19][20]

A number of other halts are still open and operational on privately owned, heritage, and preserved railways throughout the British Isles. The word is often used informally to describe national rail network stations with limited service and low usage, such as the Oxfordshire Halts on the Cotswold Line. The title halt had also sometimes been applied colloquially to stations served by public services but not available for use by the general public, being accessible only by persons travelling to/from an associated factory (for example IBM near Greenock – although this is no longer restricted – and British Steel Redcar), military base (such as Lympstone Commando) or railway yard. The only two such remaining "private" stopping places on the national system where the "halt" designation is still officially used seem to be Staff Halt (at Durnsford Road, Wimbledon) and Battersea Pier Sidings Staff Halt - both are solely for railway staff and are not open to passengers.[20]

The Great Western Railway in Great Britain, began opening haltes on 12 October 1903; from 1905, the French spelling was Anglicised to "halt". These GWR halts had the most basic facilities, with platforms long enough for just one or two carriages; some had no platform at all, necessitating the provision of steps on the carriages. There was normally no station staff at a halt, tickets being sold on the train. On 1 September 1904, a larger version, known on the GWR as a "platform" instead of a "halt", was introduced; these had longer platforms, and were usually staffed by a senior grade porter, who sold tickets, and sometimes booked parcels or milk consignments.[21][22]

From 1903 to 1947 the GWR built 379 halts and inherited a further 40 from other companies at the Grouping of 1923. Peak building periods were before the First World War (145 built) and 1928-39 (198 built)[23]). Ten more were opened by BR on ex-GWR lines. The GWR also built 34 "platforms".[24]

In many Commonwealth countries the term "halt" is still used. In the United States such stations are traditionally referred to as flag stops.

In the Republic of Ireland, a few small railway stations are designated as "halts" (Irish: stadanna, sing. stad).[25]

In Victoria, Australia, a rail motor stopping place (RMSP) is a location on a railway line where a small passenger vehicle or railmotor can stop to allow passengers to alight. It is often designated by just a sign beside the railway[26] at a convenient access point near a road. The passenger can hail the train driver to stop, and buy a ticket from the guard or the conductor on the train.[27]

Accessibility

Accessibility for people with disabilities is mandated by law in some countries. Considerations include: elevator or ramp access to all platforms, matching platform height to train floors, making wheelchair lifts available when platforms do not match vehicle floors, accessible toilets and pay phones, audible station announcements, and safety measures such as tactile marking of platform edges.

Goods stations

Goods or freight stations deal exclusively or predominantly with the loading and unloading of goods and may well have marshalling yards (classification yards) for the sorting of wagons. The world's first Goods terminal was the 1830 Park Lane Goods Station at the South End Liverpool Docks. Built in 1830 the terminal was reached by a 1.24-mile (2 km) tunnel.

As goods are increasingly moved by road, many former goods stations, as well as the goods sheds at passenger stations, have closed. In addition, many goods stations today are used purely for the cross-loading of freight and may be known as transshipment stations, where they primarily handle containers they are also known as container stations or terminals.

Largest, busiest and highest stations

Worldwide

- Tanggula Railway Station located in Amdo County, Tibet, China is currently the highest station in the world. As of 2010, no passenger transport service was available since the region is uninhabited. India's proposed Bilaspur–Mandi–Leh line, once completed, will reach an even higher elevation.

- The world's busiest passenger station, in terms of daily passenger throughput, is Shinjuku Station in Tokyo.[28] The station was used by an average of 3.64 million people per day in 2007.

- The world's largest station was Beijing West station in Beijing.[29] But subsequently, several major railway hubs have been claimed as largest in Asia and world, including but not limited to; Beijing South, Guangzhou South, Nanjing South, Shanghai Hongqiao and Xi'an North.[30] All of them are major terminals of two or more high-speed railways.

- In terms of platform capacity, the world's largest station by platforms is Grand Central Terminal in New York City with 44 platforms;[31] as part of the East Side Access Project, the MTA will be adding 4 more platforms to accommodate future Long Island Rail Road trains.

- The world's highest station above ground level (not above sea level) is Smith–Ninth Streets subway station in New York City.[32][33]

Asia

- The Shinjuku Station, in Tokyo, is Asia's busiest station by total passenger numbers.[28]

- The Shinjuku Station, in Tokyo, is Asia's largest station by number of platforms

- Beijing West station in Beijing is Asia's largest station by floor area.

Europe

Busiest

- The Gare du Nord, in Paris, is Europe's busiest station by total passenger numbers.

- Clapham Junction, in London, is Europe's busiest station by daily rail traffic (one train every 13 seconds at peak times; one train every 30 seconds at off-peak times).[34]

- Zürich Hauptbahnhof, Switzerland, is Europe's busiest terminus by daily rail traffic (Clapham Junction is a through station).

Largest

- Leipzig Hauptbahnhof in Germany is Europe's largest station by floor area (21 platforms and several levels of shopping facilities beneath).

- Berlin Hauptbahnhof is Europe's largest grade-separated and two-level station (6 upper and 8 lower platforms).

- Munich Hauptbahnhof is Europe's largest station by number of platforms (32, plus 2 additional lower platforms serving the S-Bahn, plus 6 additional platforms at two levels serving the U-Bahn).

North America

- Penn Station in New York City is the busiest station in North America.[35][36]

- Toronto's Union Station is the busiest station in Canada.[37]

Other records

- Coney Island – Stillwell Avenue in New York City is the world's largest elevated terminal with 8 tracks and 4 island platforms.[38]

- The Shanghai South Railway Station, opened in June 2006, has the world's largest circular transparent roof.[39]

- Châtelet-Les Halles, in the centre of Paris, is the busiest underground station in the world. Approximately 750,000 passengers pass through it per day.[40]

- The New Delhi Railway Station in New Delhi, India holds the record for the largest route interlock system in the world.

- Flinders Street Station in Melbourne, Australia, is the busiest train station in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere.

Bet Shan Station in Israel is the lowest elevation station in the world at 118m below sea level- this may change if the rail link to Jordan is completed as the border station will be even lower at around -270m below sea level

Gallery

- Old Atocha Station, now a greenhouse, in Madrid, Spain

Railway station in Bereket city, Turkmenistan.

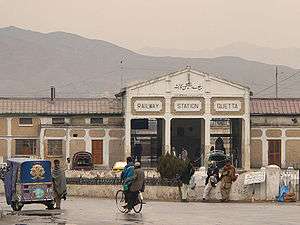

Railway station in Bereket city, Turkmenistan. The Quetta railway station.

The Quetta railway station. The famed Swiss railway clock designed in 1944 by Hans Hilfiker

The famed Swiss railway clock designed in 1944 by Hans Hilfiker The Deutsche Bahn clock in Germany

The Deutsche Bahn clock in Germany Baggage carts for refundable deposit in a German railway station

Baggage carts for refundable deposit in a German railway station

Low-lying platform at a station in the outskirts of Bern

Low-lying platform at a station in the outskirts of Bern

Antwerp Central Station in Belgium, nicknamed the "Railway Cathedral"

Antwerp Central Station in Belgium, nicknamed the "Railway Cathedral"

- London Waterloo station, as seen from the London Eye.

Luz Station in São Paulo, Brazil. Since 2006, is also the seat of Museum of the Portuguese Language.

Luz Station in São Paulo, Brazil. Since 2006, is also the seat of Museum of the Portuguese Language..jpg)

- Dunedin Railway Station, in Dunedin, New Zealand is one of the country's most famous historic buildings.[41]

.jpg)

Volos railway station, designed by Evaristo De Chirico.

Volos railway station, designed by Evaristo De Chirico.

See also

- Station building

- Bus station

- Bus stop

- Bus terminus

- Classification yard

- Goods station

- Hauptbahnhof

- Interchange station

- Intermodal freight transport

- Intermodal passenger transport

- List of IATA-indexed railway stations

- List of railway stations

- Marshalling yard

- Metro station

- Public transport

- Signal box

- Station code

- Tram stop

- Transport

- Train order station

- Paid area

- Train ticket

Notes

Sources

- Coleford, I. C. (October 2010). Smith, Martin, ed. "By GWR to Blaenau Ffestiniog (Part One)". Railway Bylines. Radstock: Irwell Press Limited. 15 (11).

- Reade, Lewis (1983). Branch Line Memories Vol 1. Redruth, Cornwall: Atlantic Transport & Historical Publishers. ISBN 0-90-689906-0.

References

- ↑ Ian Jolly (1 August 2014). "Steamed up about train stations". Academy (blog). London: BBC. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ Morana Lukač (12 November 2014). "Railway station or train station?". Bridging the Unbridgeable. A project on English usage guides (blog). Leiden, The Netherlands: Leiden University Centre for Linguistics. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ "Google Books Ngram Viewer. British English Corpus". Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ "station, noun". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ "Google Books Ngram Viewer. American English Corpus". Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ "Definition of depot by Merriam-Webster". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Hughes, Stephen (1990), The Archaeology of an Early Railway System: The Brecon Forest Tramroads, Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales, p. 333, ISBN 1871184053, retrieved 9 February 2014

- ↑ "Mumbles Railway". bbc.co.uk. 2007-03-25. Retrieved 2015-05-01.

- ↑ "B & O Transportation Museum & Mount Clare Station". National Historic Landmarks in Maryland. Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ↑ Moss, John (5 March 2007). "Manchester Railway Stations". Manchester UK. Papillon. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "The Inception of the English Railway Station". Architectural History. SAHGB Publications Limited. 4: 63–76. 1961. JSTOR 1568245. doi:10.2307/1568245. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Stations of the Gatineau Railway". Historical Society of the Gatineau. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- ↑ Miserez, Marc-André (2 June 2004). "Stations were gateways to the world". SwissInfo. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Italian Railroad Stations". History of Railroad Stations. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Technical Memorandum: Typical Cross Section for 15% Design (TM 1.1.21)" (PDF). California High-Speed Rail Program. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- 1 2 "Station Track". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Grand Central Terminal". Fodor's: New York City.

- ↑ "RPubs India".

- ↑ GB Rail Timetable Winter Edition 8 December 2013

- 1 2 "Rail Chronology: Halts and Platforms".

- ↑ MacDermot, E.T. (1931). "Chapter XI: The Great Awakening". History of the Great Western Railway. Vol. II (1st ed.). Paddington: Great Western Railway. p. 428. ISBN 0-7110-0411-0.

- ↑ Booker, Frank (1985) [1977]. The Great Western Railway: A New History (2nd ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. pp. 112–113. ISBN 0-946537-16-X.

- ↑ Coleford 2010, p. 509.

- ↑ Reade 1983, Section: In praise of halts.

- ↑ http://www.teanglann.ie/ga/eid/halt

- ↑ "Public Records Office Victoria".

- ↑ "Museum Victoria, Railmotors".

- 1 2 "Machines & Engineering: Building the Biggest". Discovery Channel. 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Shanghai to have Asia's largest railway station". Xinhua. 10 August 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "Yàzhōu zuì dà huǒchēzhàn jiūjìng yǒu jǐge?" 亚洲最大火车站究竟有几个? [Asia's largest railway stations: how many are there?] (in Chinese). RailCN.net. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ↑ Fields, W. "Regional Rail Working Group – Grand Central Terminal".

- ↑ "Rebuilding the Culver Viaduct". MTA News.

- ↑ "BROOKLYN!!" (Caption on photo from station reopening celebration). Summer 2013. p. 7.

- ↑ Simon Rogers (27 April 2013). "Every train station in Britain listed and mapped: find out how busy each one is". Rail transport Datablog (blog). Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- ↑ "State begins public review for new Moynihan Station" (Press release). Empire State Development. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ↑ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. Encyclopedia of New York City,. p. 891.

- ↑ "About Union Station". GO Transit. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ "And Now for the Good News From the Subway System; New Terminal in Coney Island Rivals the Great Train Sheds of Europe". The New York Times. 28 May 2005.

- ↑ "The railway station with world's largest transparent roof". People's Daily. Beijing. 26 June 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Un pôle de transport d'envergure régional" (PDF) (in French). RATP. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ McGill, D. and Sheehan, G. (1997) Landmarks: Notable historic buildings of New Zealand. Auckland: Godwit Publishing.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Railway station. |

- A comprehensive technical article about stations from Railway Technical Web Pages

- Branch Line Britain gives details of many railway stations throughout Britain

- Old photos of UK railway stations old photos of British railway stations before the Beeching closures

- Railway buildings photo album of railway buildings

- Railway stations photo album of railway stations around the world

- Heritage Railway Stations of Canada from Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada

- Postcards of Railroad Stations, 1903 to 1972 from the Hagley Library's Digital Archives

.jpg)