Rail transport in Israel

| Israel | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation | |||||||

| National railway | Israel Railways | ||||||

| Infrastructure company | Israel Railways | ||||||

| Major operators | Israel Railways | ||||||

| Statistics | |||||||

| Ridership | 59.5 million (heavy rail in 2016)[1] | ||||||

| Freight | 9.23 million tons (2016) | ||||||

| System length | |||||||

| Total | 1,001 km (622 mi) (2011) | ||||||

| Electrified | 13.8 kilometers | ||||||

| Track gauge | |||||||

| Main | 1,435 m | ||||||

| Features | |||||||

| No. stations | 60 | ||||||

| Highest elevation | 750m | ||||||

| |||||||

Rail transport in Israel includes heavy rail (inter-city, commuter, and freight rail) as well as light rail. Excluding light rail, the network consists of 1,001 kilometers (622 mi) of track, and is undergoing constant expansion. All of the lines are standard gauge and as of 2016 the heavy rail network is in the initial stages of an electrification programme. A government owned company, Israel Railways, manages the entire heavy rail network. Most of the network is located on the densely populated coastal plain. The only light rail line in Israel is the Jerusalem Light Rail, though another line in Tel Aviv is currently under construction. Many of the rail routes in Israel date back to before the establishment of the state – to the days of the British Mandate for Palestine and earlier. Rail infrastructure was considered less important than road infrastructure during the state's early years, and except for the construction of the coastal railway in the early 1950s, the network saw little investment until the late 1980s. In 1993, a rail connection was opened between the coastal railway from the north and southern lines (the railway to Jerusalem and railway to Beersheba) through Tel Aviv. Previously the only connection between northern railways and southern railways bypassed the Tel Aviv region – Israel's population and commercial center. The linking of the nationwide rail network through the heart of Tel Aviv was a major factor in facilitating further expansion in the overall network during in the 1990s and 2000s and as a result of the heavy infrastructure investments passenger traffic rose significantly, from about 2.5 million per year in 1990 to about 53 million in 2015.

Israel is a member of the International Union of Railways and its UIC country code is 95.[2] Currently, the country does not have railway links to adjacent countries, but one such link is planned with Jordan. Unlike road vehicles (including trams), Israeli railway trains run on the left hand tracks.

History

Ottoman Empire

Rail infrastructure in what is now Israel was first envisioned and realized during the Ottoman period. Sir Moses Montefiore, in 1839, was an early proponent of trains in the land of Israel.[3] However, the first railroad in Eretz Yisrael, also known as Palestine, was the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway, which opened on September 26, 1892.[4] A trip along the line took 3 hours and 30 minutes.[3] The line was initiated by the Jewish entrepreneur Joseph Navon and built by the French at 1 m gauge.[4] The second line in what is now Israel was the Jezreel Valley railway from Haifa to Beit She’an, which had been built in 1904[3] as part of the Haifa-Daraa branch, a 1905-built feeder line of the Hejaz Railway which ran from Medina to Damascus.[4] At the time, the Ottoman Empire ruled the Levant, but was a declining power and would succumb in World War I. During the Ottoman era, the network grew: Nablus, Kalkiliya, and Beersheba all gained train stations.[4] The First World War brought yet another rail line: the Ottomans, with German assistance, laid tracks from Beersheba to Kadesh Barnea, somewhere on the Sinai Peninsula.[4] (This line ran through trains from Afula through Tulkarm.[3]) This resulted in the construction of the eastern and southern railways.

Mideastern regional rail travel: the British Mandate

The British invaded the Levant, demolished the Kadesh Barnea line, and built a new line from Beersheba to Gaza, allowing a connection with their own line from Egypt,[4] running through Lod to Haifa.[3] In 1920 a new company, called Palestine Railways was established, which took over the responsibility of running the country's rail network. During the British Mandate, rail travel increased considerably, with a line being built between Petach Tikva and Rosh HaAyin, and Lydda (which was near the main airport in the area) becoming a major hub during WWII.[4] Also during the war, in 1942, the British opened a route running from Haifa to Beirut and Tripoli.[3] Shortly after the war expired, the Rosh HaNikra tunnel was dug, allowing train travel from Lebanon and points north (and west) to Palestine and Egypt.[4]

Starting in 1917–18, the British converted the Ottoman 1.05 m gauge southern, eastern and Jerusalem railways to standard gauge, though not the Jezreel Valley railway and some of its branches which remained narrow gauge and thus incompatible with the rest of the railways in Palestine. The British also extended some of the existing railways and connected them with adjacent countries and built 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) gauge lines in Jaffa and Jerusalem. After the First World War ended, the British nationalized all railways in the Palestine mandate and created the Palestine Railways company to manage operations.

Israel

When Israel gained independence in 1948, the state created Israel Railways as a successor to the British company. During the 1948 War of Independence, much damage was done to the railways in the country, especially the Jezreel Valley railway, which was not rebuilt due to financial constraints and its incompatibility with the rest of the rail network.

In the first years of Israeli independence, rail passenger traffic grew rapidly, reaching about 4.5 million passengers per annum during the early to mid-1960s, at which point traffic began to slacken due to improvements in the road infrastructure, increases in the automobile ownership rate, lack of investment in the rail network, and a continued favoring of public transportation using buses over trains. This trend reached a low point of about 2.5 million passengers in 1990, which on a per-capita basis represented about a 75% decrease from the heyday of the 1960s. Then in the 1990s, a wave of railway infrastructure development began, leading to a resurgence of the railways' importance within the country's transportation system.

Rail infrastructure

Heavy rail

As of 2010, the rail network in Israel spans approximately 1,000 km (620 mi), with around 250 km (160 mi) additional expected to be under construction in the early 2010s decade. The majority of the network has been double tracked, the result of extensive works which have been ongoing since around 1990 to increase capacity throughout the network.

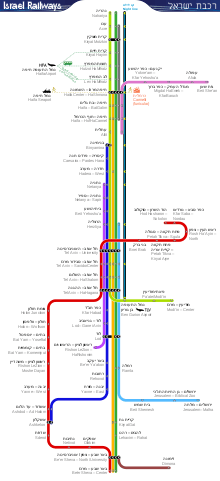

The rail network includes the coastal railway line spanning from Nahariya in the north to Tel Aviv in the south, through Acre, Haifa (with a spur to eastern Haifa), Netanya and other cities. A small commuter line goes from Kfar Saba in the north to Tel Aviv, and connects to a freight-only line from Rosh HaAyin to Lod, part of the partially defunct Eastern railway. Plans exist to rebuild the eastern railway from Hadera to Rosh HaAyin, with a spur to Afula.

Six lines go south from Tel Aviv, including two lines to Rishon LeZion, one of which continues to Yavne with a section from Yavne to Ashdod currently under construction; a line to Ashkelon through Lod and Rehovot with a spur to the Port of Ashdod; a line to Modi'in through Ben Gurion International Airport; a line to Jerusalem, which is part of the historical Jaffa–Jerusalem railway; and the railway to Beersheba, with branches to Ramat Hovav and the Israel Chemicals factories through Dimona. The railway to Beersheba is also connected to the line to Ashkelon through the Heletz railway.

In the early 2000s, the Israeli government embarked on a major project to upgrade the existing rail network and build a number of entirely new lines. This includes rebuilding the railways to Kfar Saba and Beersheba, while converting them to double-track and constructing dozens of grade separations between road and rail. Then in the 2010s decade, rebuilding the Jezreel Valley railway and creating new lines: the Railway to Karmiel, the High-speed railway to Jerusalem, a line from Ashkelon to Beersheba through Sderot, Netivot and Ofakim, and a railway as part of the Route 531 project. Some of these projects were initiated in the 2000s but were eventually frozen, with work on some resuming in 2009–2010, when they were included in a major government plan to connect almost all cities in Israel to the rail network.

The long-term plan also calls for rebuilding the Eastern railway, a railway to Eilat (Med-Red[5]), a line to Arad through Nevatim and Kseifa, a line from Modi'in to Rishon LeZion via Highway 431, a line to Nazareth and continuing the Karmiel and Jezreel Valley lines to Kiryat Shmona, Safed and Tiberias.

Electrification

As of December 2015, Israel Railways relies solely on diesel locomotives and DMUs. In the spring of 2010, the government of Israel voted to appropriate the sum of NIS 11.2 billion out of a total NIS 17.2 billion (appx. US $4.5 billion) necessary to implement the first phase of Israel Railways' electrification programme.[6] This phase includes electrifying 420 km of railways using 25 kV 50Hz AC, the construction of 14 transformer stations, the purchase of electric rolling stock, and upgrades to maintenance facilities as well as to signalling and control systems (including the installation of ETCS L2 signaling throughout the network). Preliminary design for the electrification effort was conducted by TEDEM Civil Engineering in the early 2000s, while Yanai Electrical Engineering was selected by Israel Railways in 2011 to carry out the detailed design of the system. In December 2015 Israel Railways announced that the Spanish engineering firm SEMI won the tender for constructing the electrification infrastructure.[7]

Technical characteristics

The following standards are employed throughout the mainline heavy rail network in Israel:

- Rail gauge: standard gauge (1435mm)

- Max speed: 160 km/h

- Rail type: UIC60 or UIC54 (60 kg/m or 54 kg/m), continuously welded

- Loading gauge: Equivalent to German DE2

- Common distance between track centers of double-tracked railways: 4.7m

- Train protection system: PZB

- Railway coupling: Buffers and chain (locomotive drawn), Scharfenberg (multiple unit trainsets)

- Maximum gradient: 27‰

- Max rolling stock axle load: 22.5 metric ton per axle

- Minimum number of sleepers per kilometer: 1667 (mostly B70 prestressed concrete monoblock)

- Passenger platform minimum length: 300m (with some stations built to the previous standard of 250m)

Future standards

- Electrification: Single-phase 25 kV 50Hz AC OCS

- Train control system: ERTMS (GSM-R/ETCS L2)

Sandwich stations

An interesting character of the current Israeli railway network is that many of the new tracks and railway stations are located in between the Israeli highway system. The first station built in between the two directions of a highway was the Tel Aviv Savidor Central Railway Station between the Ayalon Freeway.

Light rail

The only light rail line in Israel is the Jerusalem Light Rail, opened in 2011. The line is 13.8 km (8.6 mi) long and goes from Mount Herzl in the west, with an extension planned to Ein Kerem, to Pisgat Ze'ev in the east, with a planned extension to Neve Ya'akov.

A major LRT/BRT network is planned for the Tel Aviv metropolitan area, spanning five light rail lines for a total of 82 km (51 mi). The first (red) line will go from Petah Tikva in the northeast to west Rishon LeZion in the southwest, with a significant portion of it underground. As of 2015 the line is under construction. The second (green) line will go from Rishon LeZion and Holon in the south to north Tel Aviv. The third (purple) line will start in central Tel Aviv, go around the city and turn east. It will split into two in Kiryat Ono and reach Yehud and Or Yehuda.

In addition, a funicular underground rail line, the Carmelit, was opened in Haifa in 1959.

A tram-train linking Haifa and Nazareth is also being planned.[8]

Passenger traffic

Following the low point of 2.5 million passengers in 1990, the extensive investments in the national heavy rail infrastructure beginning in the early to mid-1990s made train travel more appealing, especially given the ever-increasing road congestion, and consequently passenger rail use began rising rapidly—by a factor of about fivefold over any given ten-year span during the 1990s and 2000s. Consequently, in the 25-year span between 1990 and 2015, heavy rail passenger traffic grew over 20-times. Moreover, with several large-scale railway infrastructure projects still underway and more planned in the future, the growth in passenger numbers is expected to continue.

Statistics

The following table includes ridership statistics for heavy rail only.

| Year | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passengers (millions) | 5.1 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 8.8 | 12.7 | 15.1 | 17.5 | 19.8 | 22.9 | 26.8 | 28.4 | 31.8 | 35.13 | 35.93 | |||||||

| Year | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passengers (millions) | 35.87 | 35.93 | ~40.37[10] | 45.1[11] | 48.5[11] | 52.8[12] | 59.5[1] | ||||||||||||||

Passenger stations

| Name | Hebrew | City | Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | עכו | Acre | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in |

| Afula | עפולה | Afula | Atlit – Beit She'an |

| Ashdod Ad Halom Ashdod South |

אשדוד עד הלום אשדוד דרום |

Ashdod | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Ashkelon | אשקלון | Ashkelon | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Atlit | עתלית | Atlit | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in |

| Bat Yam-Komemiyut | בת ים - קוממיות | Bat Yam / Holon | Hod Hasharon Sokolov – Rishon LeZion Moshe Dayan |

| Bat Yam-Yoseftal | בת-ים יוספטל | Bat Yam / Holon | Hod Hasharon Sokolov – Rishon LeZion Moshe Dayan |

| Be'er Sheva Center | באר שבע מרכז | Beersheba | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center |

| Be'er Sheva North University |

באר שבע צפון אוניברסיטה |

Beersheba | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center Be'er Sheva North – Dimona |

| Be'er Ya'akov | באר יעקב | Be'er Ya'akov | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Ben Gurion Airport | נמל תעופה בן גוריון | Ben Gurion International Airport | Nahariya – Modi'in |

| Beit She'an | בית שאן | Beit She'an | Atlit – Beit She'an |

| Beit Shemesh | בית שמש | Beit Shemesh | Tel Aviv Central – Jerusalem Malha |

| Beit Yehoshua | בית יהושע | Beit Yehoshua | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Biblical Zoo | גן החיות התנ"כי | Jerusalem | Tel Aviv Central – Jerusalem Malha |

| Binyamina | בנימינה | Binyamina-Giv'at Ada | Binyamina – Ashkelon Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in |

| Bnei Brak | בני ברק | Bnei Brak / Ramat Gan | Hod Hasharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Caesarea-Pardes Hanna | קיסריה-פרדס חנה | Pardes Hanna-Karkur Caesarea Industrial Zone |

Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Dimona | דימונה | Dimona | Be'er Sheva North – Dimona |

| Hadera West | חדרה מערב | Hadera | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Haifa Bat Galim | חיפה בת גלים | Haifa | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Haifa Hof HaCarmel – Kiryat Motzkin |

| Haifa Hof HaCarmel | חיפה חוף הכרמל | Haifa | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Haifa Hof HaCarmel – Kiryat Motzkin |

| Haifa Central | חיפה מרכז | Haifa | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Haifa Hof HaCarmel – Kiryat Motzkin |

| Herzliya | הרצליה | Herzliya | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Hod HaSharon Sokolov (Kfar Saba) |

הוד השרון סוקולוב כפר סבא |

Hod HaSharon / Kfar Saba | Hod Hasharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Holon-Wolfson | חולון-וולפסון | Holon / Tel Aviv-Yafo | Hod Hasharon Sokolov – Rishon LeZion Moshe Dayan |

| Holon Junction | צומת חולון | Holon / Tel Aviv | Hod Hasharon Sokolov – Rishon LeZion Moshe Dayan |

| Hutzot HaMifratz | חוצות המפרץ | Haifa | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Haifa Hof HaCarmel – Kiryat Motzkin |

| Jerusalem Malha | ירושלים מלחה | Jerusalem | Tel Aviv Central – Jerusalem Malha |

| Kfar Chabad | כפר חב"ד | Kfar Chabad | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Kfar Saba – Nordau (Hod HaSharon) |

כפר סבא נורדאו הוד השרון |

Kfar Saba / Hod HaSharon | Hod Hasharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Kiryat Gat | קרית גת | Kiryat Gat | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center |

| Kiryat Haim | קריית חיים | Haifa (Kiryat Haim) | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Haifa Hof HaCarmel – Kiryat Motzkin |

| Kiryat Motzkin | קריית מוצקין | Haifa (Kiryat Shmuel) Kiryat Motzkin |

Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Haifa Hof HaCarmel – Kiryat Motzkin |

| Lehavim Rahat | להבים רהט | Lehavim | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center |

| Lev HaMifratz | לב המפרץ | Haifa | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Haifa Hof HaCarmel – Kiryat Motzkin |

| Lod | לוד | Lod | Binyamina – Ashkelon Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center |

| Lod Ganei Aviv | לוד גני אביב | Lod | Hod HaSharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Migdal HaEmek – Kfar Baruch | מגדל העמק-כפר ברוך | Migdal HaEmek, Kfar Baruch | Atlit – Beit She'an |

| Modi'in Central | מודיעין מרכז | Modi'in | Nahariya – Modi'in |

| Nahariya | נהריה | Nahariya | Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in |

| Netanya | נתניה | Netanya | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Netivot | נתיבות | Netivot | Hod Hasharon – Netivot |

| Pa'atei Modi'in | פאתי מודיעין | Modi'in | Nahariya – Modi'in |

| Petah Tikva Kiryat Arye | פתח תקווה קרית אריה | Petah Tikva | Hod HaSharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Petah Tikva Segula | פתח תקווה סגולה | Petah Tikva | Hod HaSharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Ramla | רמלה | Ramla | Tel Aviv Central – Jerusalem Malha |

| Rehovot | רחובות | Rehovot | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Rishon LeZion HaRishonim | ראשון לציון הראשונים | Rishon LeZion | Tel Aviv HaHagana – HaRishonim |

| Rishon LeZion Moshe Dayan | ראשון לציון משה דיין | Rishon LeZion | Hod HaSharon Sokolov – Sderot |

| Rosh HaAyin Tzafon | ראש העין צפון | Rosh HaAyin / Neve Yerek | Hod HaSharon Sokolov – Sderot |

| Sderot | שדרות | Sderot | Hod HaSharon Sokolov – Sderot |

| Tel Aviv HaHagana | תל אביב ההגנה | Tel Aviv | Binyamina – Ashkelon Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Hod HaSharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Tel Aviv HaShalom | תל אביב השלום | Tel Aviv | Binyamina – Ashkelon Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center Hod Hasharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Tel Aviv Central Savidor |

תל אביב מרכז סבידור |

Tel Aviv / Ramat Gan | Binyamina – Ashkelon Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Tel Aviv Central – Be'er Sheva Center Hod Hasharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Tel Aviv University Convention Center |

תל אביב אוניברסיטה מרכז הירידים |

Tel Aviv | Binyamina – Ashkelon Nahariya – Be'er Sheva Center Nahariya – Modi'in Hod Hasharon Sokolov – HaRishonim |

| Yavne East | יבנה | Yavne | Binyamina – Ashkelon |

| Yavne West | יבנה מערב | Yavne | Hod Hasharon – Yavne West |

| Yokneam – Kfar Yehoshua | יקנעם-כפר יהושע | Yokneam Illit, Kfar Yehoshua | Atlit – Beit She'an |

Freight

According to official statistics, Israel Railways transported approximately seven million tons of freight in 2010. Minerals and chemicals from the Dead Sea area, such as phosphates, potash and sulphur, made up more than half of this amount.[9] As of 2011, the share of total domestic freight transported by rail is approximately 8%. The government of Israel, believing that freight rail transport in the country is underutilized, particularly with respect to container transport, has set a goal of doubling the amount of freight transported by rail by the middle of the 2010s decade and tripling it by the end of the decade. Its plan calls for an upgrade of the freight transport infrastructure, including more freight terminals, new or renewed sidings to factories and other customers, and the purchase of additional freight locomotives and freight cars. From an administrative perspective, Israel Railways' freight division will be spun off into a separate subsidiary, which will be 51% privately owned by a strategic partner committed to maximizing the railway's freight transport potential. The new subsidiary will be allowed to partner directly with other transport providers in the private sector in order to offer customers more cost-effective, flexible and complete transport and logistical solutions than those currently offered by Israel Railways.

Rail links to adjacent countries

Originally part of the Palestine Railway, a line linked East Qantara north of the Suez Canal in Egypt, skirting the Mediterranean northward to the port of Tripoli, Lebanon. In 1912, the French built an extension of the Baghdad Railway south from Aleppo, Syria, to connect at Tripoli, Lebanon. Expanded during World War II by both Australian and later New Zealand engineers, the effective footprint extended as far as Damascus.

For a railway both created and effected by the logistical need of military engineers supporting a various war efforts, on the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and the outbreak of hostilities during the Israeli War of Independence, those connections were severed and have yet to be restored.

Israeli forces bombed the rail bridge to Lebanon, and the remnants of this line can be seen at Rosh HaNikra grottoes, where a virtual "train ride to peace" movie is shown inside the sealed tunnel that used to go into Lebanon. The tracks used to continue from Rosh HaNikra to Nahariya (the current northern end of the line) making it possible for one to travel from Lebanon all the way to Tel Aviv, Cairo, and beyond. Northerly, there was a route to Syria and connection via Chemins de Fer Syriens to Damascus.

Railway links with adjacent countries

Proposed rail lines to the PA

Talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in 2004 have raised the possibility of reviving the old line from the Gaza Strip to Tulkarm and/or building a new line from Gaza to Tarkumia (near Hebron) with the aim of securely transporting people and goods between Gaza and the West Bank through Israeli territory as well as for transporting cargo to and from the Israeli port of Ashdod destined to the Palestinian Authority.[13] Another proposed line would involve the revival of the old Hejaz railway branch from Afula to Jenin.

External links

- Jaffa-Jerusalem Rail Ticket Shapell Manuscript Foundation

References

- 1 2 Gutman, Lior (1 April 2017). "רכבת ישראל: עלייה של 13% במספר הנוסעים ב-2016" [Israel Railways: 13% Increase in Passengers in 2016] (in Hebrew). Calcalist. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ↑ http://www.uic.org/IMG/xls/country_code_applicable.xls

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Milestones". Israel Railways. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Famous Engine Saved from the Scrap Yard". ERETZ Magazine. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ Moti Bassok, Cabinet examining plan for Med-Red railway. Jerusalem could invite China to help build rail link between Eilat and northern Israel. // Haaretz, 30.01.12

- ↑ Schmiel, Daniel (26 June 2012). "Israel Railways Argues Against Kat'z Plan to Transfer Control of Electrification Project to the National Roads Company". TheMarker (in Hebrew). Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ↑ Dori, Oren (6 December 2015). "הזוכה במכרז החשמול של רכבת ישראל: SEMI הספרדית" [Spanish Firm SEMI Wins Israel Railways' Electrification Tender] (in Hebrew). TheMarker. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ "Israel plans tram-train line". International Railway Journal. Retrieved 2016-10-24.

- 1 2 3 "Statistical Data" (in Hebrew). Israel Railways. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- ↑ Nissan, Yossi (February 11, 2013). "Israel Railways 2012 revenue NIS 1.58b". Globes. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- 1 2 Yeshayahou, Kobi (February 1, 2015). "Israel Railways passenger traffic up 7.5% in 2014". Globes. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Goldberg, Jeremaya (March 30, 2016). "Israel reports 9% passenger increase". International Railway Journal.

- ↑ Forward, The Jewish Daily, article published 4 February 2005