Raid on Lorient

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

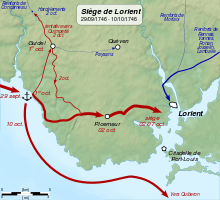

The Raid on Lorient was a British amphibious operation in the region around the town of Lorient from 29 September to 10 October 1746 during the War of the Austrian Succession. It was planned as an attempt to force the French to withdraw their forces from Flanders to reinforce their own coast. At the same time, as Lorient was used by the French East India Company as a base and supply depot, its destruction would serve British objectives in the East Indies.

Around 4500 British soldiers were embarked, but the ships carrying them had to wait off the Lorient coast several days, allowing the town to organise its defences and call in reinforcements from other towns in the region. The British troops only arrived in the outskirts of the town on 3 October and negotiations for the town's surrender were ended on by the bombardment of 5–7 October. On 7 October the British force was ordered to retreat. The British engineers' incompetence and losses to disease and fatigue forced the commander to stop his offensive. At the same time, the French commander originally planned to surrender, believing his enemy to have an overwhelming numerical superiority and knowing the weakness of his defences and the poor training and weaponry of his own troops. He made a surrender offer on 7 October, shortly after the enemy's departure, and never received a reply.

The raid is notable for its military results, such as forcing the French to develop fortifications in southern Brittany, but also for its cultural consequences, such as starting a controversy between David Hume and Voltaire and giving rise to a cult of the Virgin Mary in the town along with several songs describing the siege.

Background

War of the Austrian Succession

Following the capture of Louisbourg in 1745, the British government contemplated launching an attack on Quebec which would hand Britain control over Canada. The Duke of Bedford was the leading political supporter of a campaign. A force was prepared for this with troops under Lieutenant General James St Clair, to be escorted by a naval force under Admiral Richard Lestock. It was ready to sail by June 1746.

However, it was decided that it was too late in the year for an Atlantic crossing and operations up the St Lawrence River and the British were alarmed by the sudden departure of a French fleet under d'Anville[2] (which met with its own failure in attempting the retaking of Louisbourg). As it would be impossible to re-integrate the British force back into another one, Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle suggested to James St Clair that it be used for a landing in France. George II of England heard about the proposal and asked the general if a plan had been prepared.[3] The general told him there was not yet any such plan and that he did not know where such a landing might be made, but proposed the generals study possible landing places on the French coast.[4] In a meeting with the king, Newcastle insisted that the plan be carried through and on 29 August St Clair received orders to proceed to Plymouth to await orders for the operation.[5]

Origin of the British plan

Decision to attack Lorient

At Plymouth, St Clair received orders to sail for the French coast and attack Lorient, Rochefort, La Rochelle, Bordeaux or any other town as opportunity presented itself.[5] In a letter of 29–30 August, he favoured an operation against Bordeaux, an area he already knew and which (unlike the other towns) was unfortified. Lorient was also far enough to draw off French troops from Flanders, where they were proving very successful under the maréchal de Saxe, overrunning Austrian territory and winning several victories such as Fontenoy, Rocourt and the Brussels[6]

Admiral Anson was also in Plymouth. He met St Clair and informed him that he knew the town of Lorient in southern Brittany was poorly fortified. It was therefore decided to send the naval force to identify possible landing or raiding sites along that coast.[7][8] At the same time, Newcastle began to support a plan to land in Normandy which had been produced by major McDonald of the general staff. McDonald was sent to Plymouth to defend his plan in person before St Clair, but St Clair decided that McDonald was ignorant in military matters and if he switched from Lorient to Normandy now he would have to send his ships out on another reconnaissance mission.[9] It was finally decided to send the expeditionary force against Lorient, since it would reap a double benefit[10] - firstly, the town was the headquarters of the French East India Company, whose activities could be stopped by a raid on the town, and secondly it would act as a diversion for the French force in Flanders.[11]

British preparations

British tactics had evolved since the War of the League of Augsburg. Instead of bombarding ports and raiding the coast of Brittany as it had done during that conflict, Britain shifted more and more to larger amphibious operations such as the 1694 Battle of Camaret.[12]

Vice admiral Richard Lestock was court-martialled due to his implication in the defeat at the Battle of Toulon and appointed to head the British fleet for the new operation in Brittany in February 1744.[13] He had at his disposal 16 ships of the line, 8 frigates and 43 transport ships.[14] Shortly before the expedition's departure the historian and philosopher David Hume became secretary to James St Clair, in command of the land offensive.[15] St Clair's force was made up of the 1st Battalion of the Royal Regiment, the 5th Battalion of the Highlanders Regiment, the 3rd Battalion of Bragg's Regiment, the 2nd Battalion of Harrisson's Regiment, the 4th Battalion of Richbell's Regiment, part of some battalions from Frampton's Regiment and some companies of marines, numbering a total of 4,500 men.[14]

The commanders were doubtful as to whether Brittany was the best target for the raid, preferring Normandy.[10] Brittany was not well-known to the British - St Clair could not acquire a map of the region and had to use a small-scale map of France instead, whilst Lestock knew nothing about the town's defences.[16] The landing force was also unable to acquire horses.[16] The fleet left Plymouth on 26 September and passed Ushant without being intercepted by the French.[17]

French context

Intelligence and preparations

The French staff had been informed of the importance of the troops stationed at Plymouth by their intelligence services through interrogating British prisoners,[18] but this had not revealed the force's intended target.[19] An agent on the ground sent a message that the force had little food and few horses, suggesting a small-scale raid on the French coast. The commanders of French ports on the English Channel and Atlantic coasts were notified, notably Port-Louis on 24 September. Coastguard militias were sent to the coast,[20] though British reconnaissance along the coast went unreported.[21] At the same time ships under Mac Nemara were ordered to head for Lorient and wait.[22]

Situation around Lorient

At the end of the 17th century, the coast of Brittany was gradually covered in new fortifications, but the area around Lorient itself was still poorly defended.[12] The citadelle de Port-Louis which closed off the Lorient roads had not been modernised[23] and only low ramparts protected the city's rear, whilst its coast had no other defences.[24]

The place had become a trading port and a strategic point. Arsenals were built to construct ships for the French navy and the East India Company - the latter had chosen to move its base from Nantes to Lorient in 1732.[25] It was also a centre for cabotage between Brest, Nantes and Bordeaux.[26] To the town's south-east, Belle-Île gave shelter to ships returning from the East Indies and heading for Lorient.[27] The nearby islands of Houat and Hoëdic were fortified at the end of the 17th century to defend the approaches to the main island.[28]

A cult of the Virgin Mary developed in the area from the 1620s onwards. Apparitions of saint Anne were reported in the era near Auray and several miracles were attributed to her during earlier British raids, against a background of Protestant British forces fighting Catholic Breton ones.[29]

Raid

The expedition sailed in September, reaching the French Atlantic coast shortly afterwards. The two commanders were distinctly uncomfortable with their orders, as they believed the equinoctial gales would make the operation extremely risky, and they lacked any firm intelligence about Lorient and its defences.

The troops were landed on 20 September, and advanced towards the town. They reached its outer defences and came under fire – which led to their withdrawal. St Clair reboarded his troops and the expedition sailed back to England. In fact the townspeople had been about to surrender, so lightly defended was Lorient, and the lack of sea defences meant that Lestock could have sailed his ships into the harbour and landed them on the quayside.[30]

Opening phase

Landing

The British fleet arrived off Lorient on 29 September after six days crossing the Channel[31] and joined up with its reconnaissance vessels. A barque from Port-Louis sighted them but confused them with Mac Nemara's ships, which were expected at the same time.[32] Lestock chose the entry to the Lorient roads as his landing point due to his poor knowledge of Lorient's defences. The fleet started to anchor in Pouldu bayfrom the evening of 29 September onwards,[33] near the mouth of the Laïta. Despite favourable weather, a full moon and a good wind blowing inshore, Lestock postponed the landing until the following day,[34] leaving time for the French to prepare their defences.[35] Even so, the landing site presented several issues - it was exposed to the wind, running the risk of running the ships against the shore if a storm blew up, whilst it was 16 miles away from Lorient.[36]

The landing took place on Saturday 1 October after being cancelled due to lack of time the day before. The landing could not take place early in the morning due to unfavourable weather, allowing the Lorient coast-guards definitely to identify the fleet as British and not Mac Nemara's,[37] and time to organise their defences.[38] The British forces approached three beaches and landed in groups between 400 and 1000 men[39] under a bombardment from Lestock's ships.[40]

The first available French forces were the coast-guards, mainly made up of ill-equipped peasants, with only staffs, pikes and a few muskets[41]). Since 1744 they had been trained for 15 days each year, to limited effect.[42] There were also three companies of cavalry - with the coast-guards, this made a total of around 2,000 men under the command of marquis De L'Hôpital. Even so, only two of the three beaches could be guarded effectively,[43] and St Clair took advantage of this to land his troops.[44]

Reaction in Lorient

News of a British landing in the area reached Lorient on 30 September at around 3pm and several middle-class inhabitants of the city evacuated their possessions towards Hennebont and Vannes.[45] The alert was given and went inland as far as Noyal-Pontivy. On the same day Deschamps (commander of the citadelle de Port-Louis fortress in Morbihan) requested troops from several towns in the region.[46] They were sent on 1 and 2 October and amounted to 300 men for Vannes, two militia detachments for Josselin, some troops for Rohan, 300 men for Morlaix, a few dozen musketeers for Lamballe and a little under 1,000 men for Rennes.[47]

The retreating French forces arrived in Lorient the same evening.[48] Peasants and around 2000 men of the coastguard militias managed to fight guerilla rearguard actions[33] in the countryside separating the British positions from the town.[49] A British reconnaissance force seized Guidel on the first day[50] · [33] after fighting peasant troops and forcing them to retreat to Quéven.[51]

De L'Hôpital took command of the defences of Lorient on the evening of 1 October and immediately held a council of war. He wished to initially leave the defence of the town to the peasant militias whilst his own troops harassed the British troops in the countryside,[52] but the town's inhabitants did not agree and so he relinquished the command.[53]

March to the town and French reactions

Approaching the town

The British land offensive started on 1 October 1746[50] and immediately faced difficulties. Rain made the land hard to cross and the three miles separating the beaches from the town made it difficult to supply the besieging force with munitions and supplies.[36]

On Sunday 2 October most of the British force began marching towards Lorient, but St Clair did not have a detailed map[35] and even when he captured prisoners, they spoke Breton not French and were useless for intelligence purposes.[53] St Clair had to divide his troops into two columns, one heading for Plœmeur and the other going north towards Quimperlé.[35] The first column reached Plœmeur safely but the Quimperlé column was harassed by 300 militiamen coming from Concarneau and for a time had to retreat before turning towards Plœmeur.[54] The two columns rejoined just before Plœmeur, which was attacked and sacked before the force moved on Lorient.[54] The British came in sight of Lorient around 3pm and set up camp at Lanveur, two-thirds of a league from the city.[55][56]

French reactions

The British force send a surrender proposal to the town on the evening of 3 October 1746. St Clair required a right of pillage for four hours and a large sum of money. The French negotiators rejected the proposal the same evening - they proposed that the French force be allowed to retreat back to the town with full honours of war and a guarantee that neither the town nor the East India Company's storehouses would be pillaged by the British troops.[57] These terms were contrary to St Clair's requirements and he refused them on 4 October[58] and send orders to bring his ships' guns to the town to besiege it.[59] With no horses or pack animals, everything had to be carried on the men's backs. The peasants had also hidden all their food, adding to the troops' fatigue - many men fell sick or became unfit for duty every day.[36]

Several French militia sorties were made against the besiegers during the early days of the siege, but these were unsupported by regular troops, limiting their impact.[60] The main aim was to buy time to allow reinforcements to arrive. On the evening of Monday 3 October, major De Villeneuve arrived at Port-Louis and took command of it, from the morning of 4 October until Thursday 6 October, on which date he was replaced by the comte de Volvire, the king's commander in Brittany.[61] He was able to interview British prisoners and learn his enemy's weak points.[62]

On the evening of Wednesday 5 October, news of the landing reached Louis XV of France at Versailles. He decided to detach troops from the Flanders front and send them to the west - this included 20 infantry battalions, a dragoon regiment, two cavalry regiments and an army staff detachment.[63]

Siege and retreat

British attempts

British engineers promised to destroy the town in 24 hours but rapidly proved unable to keep that promise. Cannon were deliver without enough shot and mortars without furnaces, forcing them to stop firing.[59] A third of the British troops also had to help transport the artillery, exhausting them.[64] The siege only began in earnest on 5 October 1746[50] and the bombardment the following day.[65] However, the British guns were dug in too far from the town and only caused limited damage[59] - six were killed, twelve wounded, two houses set on fire, two others heavily damaged and fifteen more lightly damaged.[66] Mainly built of stone, with little wood, the houses of Lorient mainly proved resistant to British artillery fire.[67] David Hume summed up the situation :

The men seemed to fall prey to doubt. The sight of a dozen Frenchmen struck terror into our lines - Bragg's and Frampton's troops even exchanged several bursts of fire with them. Everyone was discourage, and the rain (which fell for three days) was largely responsible. The route from the camp to the rest of the fleet was rendered impassable.[59]

The British force began to shrink thanks to exhaustion and sickness. Only 3,000 men were still fit for combat on the evening of 6 October. They had to face militia sorties and defend their camp on the Keroman moorland.[68] They gained information from deserters on 6 October, as well as from a black slave[69] and prostitutes, made the British believe that a force of nearly 20,000 men were waiting within the town and that a massive counter-attack was imminent.[70]

Storms were expected and so Lestock sent word that he could no longer remain offshore.[71] St Clair concluded that he would have to raise the siege. A council of war on the evening of 6 October did not come to a definite decision, but retreat was much talked of.[72] The bombardment of the town was still proving unsuccessful on the following day (7 October) and during the afternoon the British decided to retreat, abandoning the camp whilst the artillery continued to bombard the town to hide the force's retreat.[73] Only on Sunday 9 October did the last troops re-embark, though a headwind prevented immediate departure[74] and the fleet only sailed on 10 October.[50]

French defences

The town prepared its defences - cannon were brought off ships and installed on the town's ramparts, new defences were built and the garrison was boosted by the arrival of troops from Port-Louis.[75] On 6 October almost 15,000 militiamen were in the town, but they were all inexperienced and undisciplined.[66] On the same day the French guns began replying to the British bombardment, using better-quality shot - the French fired chain shot and grapeshot whilst the British used bombs and exploding grenades.[68] The following day (7 October) around 4,000 shot were fired against the British[76] Three British deserters were also captured, revealing that the British force only amounted to 3,000 men and not the rumoured 20,000.[59]

Late 18th century Breton militia song[77] -

Les Anglais, remplis d'arrogance, The English, full of arrogance

Sont venus attaquer Lorient ; Came to attack Lorient ;

Mais les Bas-Bretons, But the Low-Bretons,

À coups de bâtons, Beat them with sticks

Les ont renvoyés And sent them back

Hors de ces cantons. Out of these counties.

On the evening of 7 October, a British shot fell near the French command centre, leading to a council of war. De Volvire and de L'Hôpital backed surrender, thinking that the British were about to reinforce their firepower.[78] The town's commander did not believe that his troops could win, thinking weaker than the British troops,[79] but his officers and the town's inhabitants opposed surrender,[80] stating they were ready to defend the town to the last bullet.[81] It was thus decided to surrender,[80] and on 7 October at 7pm De L'Hôpital left the town carrying its surrender proposal.[82] He was unable to find the enemy force and had to return to Lorient around 10pm.[83] He suspected a British ruse and ordered the town's defences reinforced.[79]

On the following day (8 October) the French cannon and mortars were found in what was left of the besiegers' camp[84] and that evening the peasants of Plœmeur brought the town news of British retreat.[85] The coastguard militia harassed the British force as it retreated, but the French cavalry and dragoons refused to take part in those operations.[86] No attempt was made to stop the British fleet as it passed Port-Louis on 10 October, for fear of a second landing there.[87] The inhabitants of Lorient were also on the alert against British reinforcemenets landing in the region.[88]

News of the siege reached Paris via Versailles, alarming the shareholders of France's East India Company.[89] De L'Hôpital arrived in Paris on 14 October and met the king. Omitting to mentions his mistakes, his account of the battle promoted his and De Volvire's role in it and thus gained him advancement and financial advantage.[90]

Aftermath

The concept of Naval Descents, such as Lorient, became fashionable again in the 1750s during the Seven Years' War when Britain launched a number of raids against towns and islands along the French coast in a bid to destabilise the French war effort in Germany. Britain launched raids on Rochefort, Cherbourg and St Malo during the war.

Military results

Later raids on southern Britanny

The British fleet headed to the east of Lorient to start attacking several points along the coast until on 10 October a storm hit and five transports with around 900 men lost touch with the rest of the fleet. Without orders of their own, these ships sailed back to Britain. Three battalions of reinforcements had been promised and were expected by the commanders but never arrived.[91]

The Quiberon peninsula was occupied and pillaged between 14 and 20 October. The island of Houat was also attacked on 20 October and Hoëdic on 24 October.[92] The defences built on these islands by Vauban were captured without a shot being fired and razed to the ground.[93] Belle-Île-en-Mer was blockaded until the squadron left on 29 October. The many raids disrupted trade in the region but the operation had no effect on the War of the Austrian Succession.[92]

After receiving news of the allied defeat at the battle of Rocourt and of the probable arrival of French reinforcements in Brittany, the commanders decided to sail back to Britain. The fleet was battered by strong winds and scattered, with some of them sailing for Spithead and the majority of the transports and other ships (still under Lestock's command) setting course for Cork, which they reached in early November.[91]

News of the defeat reached Britain before Lestock did and he was forced to surrender his command, dying a month later.[91] In December the same year The Gentleman's Magazine published a letter from someone presenting himself as well-informed about the expedition and accusing the admiral of being under the influence of a prostitute during the campaign and of letting her run councils of war on board. Nicholas Tindal repeated these accusations to explain the expedition's failure.[94]

Fortification of southern Britanny

The British raid reminded the French of the weaknesses in the region's defences. Several measures were put in place from 1750 onwards and the duc d'Aiguillon arrived as the new governor of Brittany. He divided the coast into twenty 'capitaineries', each with a battalion and improved land communication routes and the battalions' training.[95]

A new network of defences was begun around Lorient. Hornworks were built on pointe de Pen Mané and at Locmiquélic from 1761 to 1779 to protect the Lorient arsenal, a battery at Fort-Bloqué in 1749 (expanded in 1755) to protect the region's southwest coast. Further to the west was fort du Loch, built in 1756. Inland, the approaches to the town were fortified with two lunettes, one at Kerlin in 1755 and the other at Le Faouëdic in 1758.[96]

New fortifications were also begun in a zone from the Glénan archipelago in the west to île Dumet in the east. At the latter a circular battery and barracks were built between 1756 and 1758. On the Quiberon peninsula a new fort was completed in 1760, barring entry at Penthièvre. The fortifications of Houat and Hoëdic were rebuilt between 1757 and 1759 and fort Cigogne was built on the Glénan archipelago in 1755.[96]

Cultural results

Controversy between Hume and Voltaire

After the battle a controversy developed between Voltaire and Hume over their accounts of the battle.[97] One version of Histoire de la guerre de mil sept cent quarante et un attributed to Voltaire (he later challenged the version's authenticity, stating it was made from stolen drafts and formed a "shapeless and disfigured heap" of his manuscripts) published in 1755 dealt with the British operation at Lorient in 1746. It held St Clair responsible for the British defeat and used unflattering words to decry all his actions before concluding:

All this grand force produced nothing but mistakes and ridicule, in a war in which everything else remained too serious and too terrible[98]

.

It reached Hume and in January 1756 he got in contact with another veteran of the expedition to write a new account that would be more favourable to St Clair. Many close to him pushed him to published it and a draft was written.[94] Descent on the coast of Brittany in 1746, and the causes of its failure was completed the same year, just after the outbreak of the Seven Years' War. In it Hume attacked Voltair without naming him.[99]

A certain foreign writer, more anxious to tell his stories in an enter- taining manner than to assure himself of their reality, has endeavoured to put this expedition in a ridiculous light; but as there is not one circum- stance of his narration, which has truth in it, or even the least appearance of truth, it would be needless to lose time in refuting it[99]

Earlier, in April, an anonymous letter was published in the Monthly Review - this was later signed by Hume[99] and is attributed to him by several scholars. A French translation of it was published in the Journal britannique in 1756 but it did not draw a reply.[100]

Marian cult and political recovery

On 15 November 1746 the town authorities in Lorient met and arrived at the conclusion that their victory had been due to an intervention by the Virgin Mary. It was thus decided to hold an annual celebration mass in the town's parish church of Saint-Louis on 7 October, followed by a procession through the town. The bishop of Vannes approved the decision on 23 February 1747.[101] One statue was thus produced showing the Virgin as a warrior saint along the lines of Joan of Arc, sitting on the arms of the city as a pedestal and using her sceptre to beat a lion with the British arms on his sword and shield[102] - this was melted down during the French Revolution, though a larger replica was produced in the 19th century.[103]

Between the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century, the cult took a major part in the city's politics and was opposed on two fronts. Opposition between the Church and State found a particularly strong echo in the town when the mayor Adolphe L'Helgouarc'h discussed banning the procession. The ceremony thus became a demonstration of opposition to the state. The local press also used it around that time to show opposition to Protestant Britain - 7 October was also the anniversary of the 1571 battle of Lepanto between the Catholic and Ottoman fleets and was frequently used by Catholic opposition parties. For example, in 1898 La Croix du Morbihan talked of L'Helgouarc'h's administration as an "English municipal council". It was also used this way during the Fashoda Crisis of 1898[104] and during World War Two to condemn the British after the attack on Mers-el-Kébir and the British bombing of Lorient.[105]

Songs and poetry

Louis Le Cam referred to the events in a short six-verse poem describing the British's arrival in the Lorient region.[106] A slightly longer chanson also exists, speaking of a young woman who commits suicide rather than let British soldiers assault her - this probably refers to Brittany's motto "Plutôt la mort que la souillure" (sooner death than defilement). At the end of the 19th century the abbé Jean-Mathurin Cadic wrote a long poem describing the different stages of the British campaign.[107]

Notes

- ↑ The British sources can give different dates - the Julian calendar was in use in Britain until 1752, whereas France had used the Gregorian calendar from 1564 onwards.

References

- 1 2 3 Siège de Lorient par les Anglais, Institut culturel de Bretagne, accessed on www.skoluhelarvro.org 28 August 2011

- ↑ Dull 2005, p.15.

- ↑ Louis Le Cam, 1931, page 24

- ↑ Louis Le Cam, 1931, page 25

- 1 2 Louis Le Cam, 1931, page 26

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 27)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 28)

- ↑ Rodger 2006, p.248.

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 29)

- 1 2 (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 6)

- ↑ (N.A.M. Rodger 2006, p. 248)

- 1 2 (Guillaume Lécuillier 2007, paragraph 14)

- ↑ John Lingard, Histoire d'Angleterre depuis première invasion des Romains jusqu'à nos jours, Paris, Parent-Desbarres, 1842, 549 pages, p.216

- 1 2 (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 22)

- ↑ (in French) André-Louis Leroy, David Hume, Presses Universitaires De France, p 7

- 1 2 (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 7)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 43)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 33)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 34)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 35)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 36)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 39)

- ↑ Template:Glad

- ↑ (Chaumeil 1939, p. 72)

- ↑ (Chaumeil 1939, p. 70)

- ↑ (Christophe Cerino 2007, paragraph 4)

- ↑ (Christophe Cerino 2007, paragraph 7)

- ↑ (Guillaume Lécuillier 2007, paragraph 9)

- ↑ (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 1)

- ↑ Rodger 2006, p.248–249.

- ↑ (David Hume 1830, p. 386)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 42)

- 1 2 3 (Arthur de La Borderie 1894, p. 245)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 45)

- 1 2 3 (Ernest Campbell Mossner 2001, p. 195)

- 1 2 3 (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 8)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 48)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 49)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 65)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 70)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 51)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 53)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 66)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 69)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 74)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 54)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, pp. 58–59)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 71)

- ↑ (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 9)

- 1 2 3 4 (Christophe Cerino 2007, paragraph 18)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 73)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 75)

- 1 2 (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 76)

- 1 2 (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 78)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 80)

- ↑ (Arthur de La Borderie 1894, p. 246)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 88)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 90)

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Ernest Campbell Mossner 2001, p. 196)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 81)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 85)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 97)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 116)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 109)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 113)

- 1 2 (Arthur de La Borderie 1894, p. 248)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 133)

- 1 2 (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 117)

- ↑ The town was part of the Atlantic slave trade from 1720 until 1790 and especially after 1732, when the East India Company decided to move all its business from Nantes to Lorient. Around 43,000 slaves were deported by expeditions setting out from Lorient.

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 120)

- ↑ (David Hume 1830, p. 388)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 121)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 125)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 148)

- ↑ (David Hume 1830, p. 387)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 129)

- ↑ Joseph Vingtrinier, 1789-1902. Chants et chansons des soldats de France, Paris, A.Méricant, 1902, p 7

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 134)

- 1 2 (Arthur de La Borderie 1894, p. 249)

- 1 2 (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 135)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 136)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 137)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 139)

- ↑ (Ernest Campbell Mossner 2001, p. 197)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 141)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 143)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 151)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 155)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 122)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 163)

- 1 2 3 (Ernest Campbell Mossner 2001, p. 198)

- 1 2 (Christophe Cerino 2007, paragraph 19)

- ↑ (Guillaume Lécuillier 2007, paragraph 15)

- 1 2 (Ernest Campbell Mossner 2001, p. 199)

- ↑ (Guillaume Lécuillier 2007, paragraph 17)

- 1 2 (Guillaume Lécuillier 2007, paragraph 18)

- ↑ (Paul H. Meyer 1951, p. 429)

- ↑ (Paul H. Meyer 1951, p. 431)

- 1 2 3 (Paul H. Meyer 1951, p. 432)

- ↑ (Paul H. Meyer 1951, p. 434)

- ↑ (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 12)

- ↑ (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 14)

- ↑ (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 17)

- ↑ (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 19)

- ↑ (Pierrick Pourchasse 2007, paragraph 21)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 79)

- ↑ (Louis Le Cam 1931, p. 190)

- Sources

Coordinates: 47°45′00″N 3°22′00″W / 47.7500°N 3.3667°W