Rado graph

In the mathematical field of graph theory, the Rado graph, Erdős–Rényi graph, or random graph is a countably infinite graph that can be constructed (with probability one) by choosing independently at random for each pair of its vertices whether to connect the vertices by an edge. The same graph can also be constructed non-randomly, by symmetrizing the membership relation of the hereditarily finite sets, by applying the BIT predicate to the binary representations of the natural numbers, or as an infinite Paley graph that has edges connecting pairs of prime numbers congruent to 1 mod 4 when one is a quadratic residue modulo the other.

Every finite or countably infinite graph is an induced subgraph of the Rado graph, and can be found as an induced subgraph by a greedy algorithm that builds up the subgraph one vertex at a time. The Rado graph is uniquely defined, among countable graphs, by an extension property that guarantees the correctness of this algorithm: no matter which vertices have already been chosen to form part of the induced subgraph, and no matter what pattern of adjacencies is needed to extend the subgraph by one more vertex, there will always exist another vertex with that pattern of adjacencies that the greedy algorithm can choose.

The Rado graph is highly symmetric: any isomorphism of its induced subgraphs can be extended to a symmetry of the whole graph. The first-order logic sentences that are true of the Rado graph are also true of almost all random finite graphs, and the sentences that are false for the Rado graph are also false for almost all finite graphs. In model theory, the Rado graph forms an example of a saturated model of an ω-categorical and complete theory.

The names of this graph honor Richard Rado, Paul Erdős, and Alfréd Rényi, mathematicians who studied it in the early 1960s. It appears even earlier in the work of Wilhelm Ackermann (1937).

History

The Rado graph was first constructed by Ackermann (1937) in two ways, with vertices either the hereditarily finite sets or the natural numbers. (Strictly speaking Ackermann described a directed graph, and the Rado graph is the corresponding undirected graph given by forgetting the directions on the edges.) Erdős & Rényi (1963) constructed the Rado graph as the random graph on a countable number of points. They proved that it has infinitely many automorphisms, and their argument also shows that it is unique though they did not mention this explicitly. Richard Rado (1964) rediscovered the Rado graph as a universal graph, and gave an explicit construction of it with vertex set the natural numbers essentially equivalent to one of Ackermann's constructions.

Constructions

Binary numbers

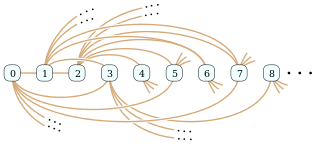

Ackermann (1937) and Rado (1964) constructed the Rado graph using the BIT predicate as follows. They identified the vertices of the graph with the natural numbers 0, 1, 2, ... An edge connects vertices x and y in the graph (where x < y) whenever the xth bit of the binary representation of y is nonzero. Thus, for instance, the neighbors of vertex 0 consist of all odd-numbered vertices, because the numbers whose 0th bit is nonzero are exactly the odd numbers. The neighbors of vertex 1 consist of vertex 0 (previously identified because 1 is odd) and all vertices with numbers congruent to 2 or 3 modulo 4 (because those are exactly the numbers with a nonzero bit at index 1), every one of which is greater than 1.

Random graph

The Rado graph arises almost surely in the Erdős–Rényi model of a random graph on countably many vertices. Specifically, one may form an infinite graph by choosing, independently and with probability 1/2 for each pair of vertices, whether to connect the two vertices by an edge. With probability 1 the resulting graph has the extension property, and is therefore isomorphic to the Rado graph. This construction also works if any fixed probability p not equal to 0 or 1 is used in place of 1/2.[1]

This result, shown by Paul Erdős and Alfréd Rényi in 1963,[2] justifies the definite article in the common alternative name “the random graph” for the Rado graph. For finite graphs, repeatedly drawing a graph from the Erdős–Rényi model will often lead to different graphs, but for countably infinite graphs the model almost always produces the same graph.

Since one obtains the same random process by inverting all choices, the Rado graph is also self-complementary.[3]

Other constructions

In one of Ackermann's original 1937 constructions, the vertices of the Rado graph are indexed by the hereditarily finite sets, and there is an edge between two vertices exactly when one of the corresponding finite sets is a member of the other. A similar construction can be based on Skolem's paradox, the fact that there exists a countable model for the first-order theory of sets. One can construct the Rado graph from such a model by creating a vertex for each set, with an edge connecting each pair of sets where one set in the pair is a member of the other.[4]

The Rado graph may also be formed by a construction resembling that for Paley graphs. Take as the vertices of a graph all the prime numbers that are congruent to 1 modulo 4, and connect two vertices by an edge whenever one of the two numbers is a quadratic residue modulo the other (by quadratic reciprocity and the restriction of the vertices to primes congruent to 1 mod 4, this is a symmetric relation, so it defines an undirected graph). Then, for any sets U and V, by the Chinese remainder theorem, the numbers that are quadratic resides modulo every prime in U and nonresidues modulo every prime in V form a periodic sequence, so by Dirichlet's theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions this number-theoretic graph has the extension property.[5]

Another construction of the Rado graph shows that it is an infinite circulant graph, with the integers as its vertices and with an edge between each two integers whose distance (the absolute value of their difference) belongs to a particular set S. For this construction to yield the Rado graph, S must have the property that adjacencies defined in this way have the extension property. This may be achieved by choosing S randomly, or by choosing the indicator function of S to be the concatenation of all finite binary sequences.[6]

The Rado graph can also be constructed as the block intersection graph of an infinite block design in which the number of points and the size of each block are countably infinite.[7]

Properties

Extension

The Rado graph satisfies the following extension property: for any finite disjoint sets of vertices U and V, there exists a vertex x connected to everything in U, and to nothing in V. For instance, with the binary-number definition of the Rado graph, let

Then the nonzero bits in the binary representation of x cause it to be adjacent to everything in U. However, x has no nonzero bits in its binary representation corresponding to vertices in V, and x is so large that the xth bit of every element of V is zero. Thus, x is not adjacent to any vertex in V.

With the random-graph definition of the Rado graph, each vertex outside the union of U and V has probability 1/2|U| + |V| of fulfilling the extension property, independently of the other vertices. Therefore, with probability one, there exists a vertex that fulfils the extension property.[1]

Induced subgraphs

This idea of finding vertices adjacent to everything in one subset and nonadjacent to everything in a second subset can be used to build up isomorphic copies of any finite or countably infinite graph G, by adding one vertex at a time without backtracking. The extension property can be rephrased as stating that this greedy algorithm can never get stuck. For, let Gi denote the subgraph of G induced by its first i vertices, and suppose that Gi has already been identified as an induced subgraph of a subset S of the vertices of the Rado graph. Let v be the next vertex of G, let U be the neighbors of v in Gi, and let V be the non-neighbors of v in Gi. If x is a vertex of the Rado graph that is adjacent to every vertex in U and nonadjacent to every vertex in V, then S ∪ {x} induces a subgraph isomorphic to Gi + 1.

By induction, starting from the 0-vertex subgraph, every finite or countably infinite graph is an induced subgraph of the Rado graph.

Uniqueness

The Rado graph is, up to graph isomorphism, the only countable graph with the extension property. For, let G and H be two graphs with the extension property, let Gi and Hi be isomorphic induced subgraphs of G and H respectively, and let gi and hi be the first vertices in an enumeration of the vertices of G and H respectively that do not belong to Gi and Hi. Then, by applying the extension property twice, one can find isomorphic induced subgraphs Gi + 1 and Hi + 1 that include gi and hi together with all the vertices of the previous subgraphs. By repeating this process, one may build up a sequence of isomorphisms between induced subgraphs that eventually includes every vertex in G and H. Thus, by the back-and-forth method, G and H must be isomorphic.[8]

Symmetry

By applying the back-and-forth construction to any two isomorphic finite subgraphs of the Rado graph, it can be shown that the Rado graph is ultrahomogeneous: any isomorphism between any two induced finite subgraphs of the Rado graph extends to an automorphism of the entire Rado graph.[8] In particular, there is an automorphism taking any ordered pair of adjacent vertices to any other such ordered pair, so the Rado graph is a symmetric graph.

The automorphism group of the Rado graph is a simple group, whose number of elements is the cardinality of the continuum. Every subgroup of this group whose index is less than the cardinality of the continuum can be sandwiched between the pointwise stabilizer and the stabilizer of a finite set of vertices.[9]

Because of its construction as an infinite circulant, the symmetry group of the Rado graph includes automorphisms that generate a transitive infinite cyclic group. The difference set of this construction (the set of distances in the integers between adjacent vertices) can be constrained to include the difference 1, without affecting the correctness of this construction, from which it follows that the Rado graph contains an infinite Hamiltonian path whose symmetries are a subgroup of the symmetries of the whole graph.[10]

Robustness against finite changes

If a graph G is formed from the Rado graph by deleting any finite number of edges or vertices, or adding a finite number of edges, the change does not affect the extension property of the graph: for any pair of sets U and V it is still possible to find a vertex in the modified graph that is adjacent to everything in U and nonadjacent to everything in V, by adding the modified parts of G to V and applying the extension property in the unmodified Rado graph. Therefore, any finite modification of this type results in a graph that is isomorphic to the Rado graph.[11]

Partition

For any partition of the vertices of the Rado graph into two sets A and B, or more generally for any partition into finitely many subsets, at least one of the subgraphs induced by one of the partition sets is isomorphic to the whole Rado graph. Cameron (2001) gives the following short proof: if none of the parts induces a subgraph isomorphic to the Rado graph, they all fail to have the extension property, and one can find pairs of sets Ui and Vi that cannot be extended within each subgraph. But then, the union of the sets Ui and the union of the sets Vi would form a set that could not be extended in the whole graph, contradicting the Rado graph's extension property. This property of being isomorphic to one of the induced subgraphs of any partition is held by only three countably infinite undirected graphs: the Rado graph, the complete graph, and the empty graph.[12] Bonato, Cameron & Delić (2000) and Diestel et al. (2007) investigate infinite directed graphs with the same partition property; all are formed by choosing orientations for the edges of the complete graph or the Rado graph.

A related result concerns edge partitions instead of vertex partitions: for every partition of the edges of the Rado graph into finitely many sets, there is a subgraph isomorphic to the whole Rado graph that uses at most two of the colors. However, there may not necessarily exist an isomorphic subgraph that uses only one color of edges.[13]

Model theory and 0-1 laws

Fagin (1976) used the Rado graph to prove a zero–one law for first-order statements in the logic of graphs. When such a statement is true or false for the Rado graph, it is also true or false (respectively) for almost all finite graphs.

First order properties

The first-order language of graphs is the collection of well-formed sentences in mathematical logic formed from variables representing the vertices of graphs, universal and existential quantifiers, logical connectives, and predicates for equality and adjacency of vertices.[14] For instance, the condition that a graph does not have any isolated vertices may be expressed by the sentence

where the symbol indicates the adjacency relation between two vertices. This sentence is true for some graphs, and false for others; a graph is said to model , written , if is true of the vertices and adjacency relation of .

The extension property of the Rado graph may be expressed by a collection of first-order sentences , stating that for every choice of vertices in a set and vertices in a set , all distinct, there exists a vertex adjacent to everything in and nonadjacent to everything in .[15] For instance, can be written as

Completeness

Gaifman (1964) proved that the sentences , together with additional sentences stating that the adjacency relation is symmetric and antireflexive (that is, that a graph modeling these sentences is undirected and has no self-loops), are the axioms of a complete theory. This means that, for each first-order sentence , exactly one of and its negation can be proven from these axioms.[16] Because the Rado graph models the extension axioms, it models all sentences in this theory

In logic, a theory that has only one model (up to isomorphism) with a given infinite cardinality λ is called λ-categorical. The fact that the Rado graph is the unique countable graph with the extension property implies that it is also the unique countable model for this theory. This uniqueness property of the Rado graph can be expressed by saying that the theory is ω-categorical. Łoś and Vaught proved in 1954 that when a theory is λ–categorical (for some infinite cardinal λ) and, in addition, has no finite models, then the theory must be complete.[17] Therefore, Gaifman's theorem that the theory of the Rado graph is complete follows from the uniqueness of the Rado graph by the Łoś–Vaught test.[18]

Finite graphs and computational complexity

As Fagin (1976) proved using the compactness theorem, the sentences of this theory (that is, the sentences provable from the extension axioms and modeled by the Rado graph) are exactly the sentences whose probability of being modeled by a random n-vertex graph (chosen uniformly at random among all graphs on n labeled vertices) approaches one in the limit as n approaches infinity. It follows that every first-order sentence is either almost always true or almost always false for random graphs, and these two possibilities can be distinguished by determining whether the Rado graph models the sentence.[19] Based on this equivalence, the theory of sentences modeled by the Rado graph has been called "the theory of the random graph" or "the almost sure theory of graphs".

Because of the 0-1 law, it is possible to test whether any particular first-order sentence is modeled by the Rado graph in a finite amount of time, by choosing a large enough value of n and counting the number of n-vertex graphs that model the property. However, here, "large enough" is at least exponential in the size of the sentence, because the extension axiom Ek,0 implies the existence of a (k + 1)-vertex clique, which is only true with high probability in random n-vertex graphs when n is exponential in k. It is unlikely that determining whether the Rado graph models a given sentence can be done more quickly than exponential time, as the problem is PSPACE-complete.[20]

Saturated model

From the model theoretic point of view, the Rado graph is an example of a saturated model.[21] This is just a logical formulation of the property that the Rado graph contains all finite graphs as induced subgraphs.

In this context, a type is a set of variables together with a collection of constraints on the values of some or all of the predicates determined by those variables; a complete type is a type that constrains all of the predicates determined by its variables. In the theory of graphs, the variables represent vertices and the predicates are the adjacencies between vertices, so a complete type specifies whether an edge is present or absent between every pair of vertices represented by the given variables. That is, a complete type specifies the subgraph that a particular set of vertex variables induces.[21]

A saturated model is a model that realizes all of the types that have a number of variables at most equal to the cardinality of the model.The Rado graph has induced subgraphs of all finite or countably infinite types, so it is saturated.[21]

Related concepts

Although the Rado graph is universal for induced subgraphs, it is not universal for isometric embeddings of graphs, where an isometric embedding is a graph isomorphism which preserves distance. The Rado graph has diameter two, and so any graph with larger diameter does not embed isometrically into it. Moss (1989, 1991) has investigated universal graphs for isometric embedding; he finds a family of universal graphs, one for each possible finite graph diameter. The graph in his family with diameter two is the Rado graph.

The Henson graphs are countable graphs (one for each positive integer i) that do not contain an i-vertex clique, and are universal for i-clique-free graphs. They can be constructed as induced subgraphs of the Rado graph.[10] The Rado graph, the Henson graphs, the disjoint unions of isomorphic cliques, and the complements of disjoint unions of cliques are the only possible countably infinite homogeneous graphs.[22]

The universality property of the Rado graph can be extended to edge-colored graphs; that is, graphs in which the edges have been assigned to different color classes, but without the usual edge coloring requirement that each color class form a matching. For any finite or countably infinite number of colors χ, there exists a unique countably-infinite χ-edge-colored graph Gχ such that every partial isomorphism of a χ-edge-colored finite graph can be extended to a full isomorphism. With this notation, the Rado graph is just G1. Truss (1985) investigates the automorphism groups of this more general family of graphs.

Shelah (1984, 1990) investigates universal graphs with uncountably many vertices.

Notes

- 1 2 See Cameron (1997), Fact 1 and its proof.

- ↑ Erdős & Rényi (1963). Erdős and Rényi use the extension property of graphs formed in this way to show that they have many automorphisms, but do not observe the other properties implied by the extension property. They also observe that the extension property continues to hold for certain sequences of random choices in which different edges have different probabilities of being included.

- ↑ Cameron (1997), Proposition 5.

- ↑ Cameron (1997), Theorem 2.

- ↑ Cameron (1997, 2001)

- ↑ Cameron (1997), Section 1.2.

- ↑ Horsley, Pike & Sanaei (2011)

- 1 2 Cameron (2001).

- ↑ Cameron (1997), Section 1.8: The automorphism group.

- 1 2 Henson (1971).

- ↑ Cameron (1997), Section 1.3: Indestructability.

- ↑ Cameron (1990); Diestel et al. (2007).

- ↑ Pouzet & Sauer (1996).

- ↑ Spencer (2001), Section 1.2, "What Is a First Order Theory?", pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Spencer (2001), Section 1.3, "Extension Statements and Rooted Graphs", pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Gaifman (1964); Marker (2002), Theorem 2.4.2, p. 50.

- ↑ Łoś (1954); Vaught (1954); Enderton (1972), p. 147.

- ↑ Marker (2002), Theorem 2.2.6, p. 42.

- ↑ Fagin (1976); Marker (2002), Theorem 2.4.4, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Grandjean (1983).

- 1 2 3 Lascar (2002).

- ↑ Lachlan & Woodrow (1980).

References

- Ackermann, Wilhelm (1937), "Die Widerspruchsfreiheit der allgemeinen Mengenlehre", Mathematische Annalen, 114 (1): 305–315, doi:10.1007/BF01594179

- Bonato, Anthony; Cameron, Peter; Delić, Dejan (2000), "Tournaments and orders with the pigeonhole property", Canadian Mathematical Bulletin, 43 (4): 397–405, MR 1793941, doi:10.4153/CMB-2000-047-6.

- Cameron, Peter J. (1990), Oligomorphic permutation groups, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, 152, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38836-8, MR 1066691.

- Cameron, Peter J. (1997), "The random graph", The mathematics of Paul Erdős, II, Algorithms Combin., 14, Berlin: Springer, pp. 333–351, MR 1425227, arXiv:1301.7544

.

. - Cameron, Peter J. (2001), "The random graph revisited", European Congress of Mathematics, Vol. I (Barcelona, 2000), Progr. Math., 201, Basel: Birkhäuser, pp. 267–274, MR 1905324.

- Diestel, Reinhard; Leader, Imre; Scott, Alex; Thomassé, Stéphan (2007), "Partitions and orientations of the Rado graph", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 359 (5): 2395–2405, MR 2276626, doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-06-04086-4.

- Enderton, Herbert B. (1972), A mathematical introduction to logic, Academic Press, New York-London, MR 0337470.

- Erdős, P.; Rényi, A. (1963), "Asymmetric graphs", Acta Mathematica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 14: 295–315, MR 0156334, doi:10.1007/BF01895716.

- Fagin, Ronald (1976), "Probabilities on finite models" (PDF), The Journal of Symbolic Logic, 41 (1): 50–58, MR 0476480, doi:10.1017/s0022481200051756.

- Gaifman, Haim (1964), "Concerning measures in first order calculi", Israel Journal of Mathematics, 2: 1–18, MR 0175755, doi:10.1007/BF02759729.

- Grandjean, Étienne (1983), "Complexity of the first-order theory of almost all finite structures", Information and Control, 57 (2-3): 180–204, MR 742707, doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(83)80043-6.

- Horsley, Daniel; Pike, David A.; Sanaei, Asiyeh (2011), "Existential closure of block intersection graphs of infinite designs having infinite block size", Journal of Combinatorial Designs, 19 (4): 317–327, MR 2838911, doi:10.1002/jcd.20283.

- Henson, C. Ward (1971), "A family of countable homogeneous graphs", Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 38: 69–83, MR 0304242, doi:10.2140/pjm.1971.38.69.

- Lachlan, A. H.; Woodrow, Robert E. (1980), "Countable ultrahomogeneous undirected graphs", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 262 (1): 51–94, MR 583847, doi:10.2307/1999974.

- Lascar, D. (2002), "Automorphism groups of saturated structures; a review", Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians, Vol. II (Beijing, 2002) (PDF), Higher Ed. Press, Beijing, pp. 25–33, MR 1957017, arXiv:math/0304205

.

. - Łoś, J. (1954), "On the categoricity in power of elementary deductive systems and some related problems", Colloquium Math., 3: 58–62, MR 0061561.

- Marker, David (2002), Model theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 217, Springer-Verlag, New York, ISBN 0-387-98760-6, MR 1924282.

- Moss, Lawrence S. (1989), "Existence and nonexistence of universal graphs", Polska Akademia Nauk. Fundamenta Mathematicae, 133 (1): 25–37, MR 1059159.

- Moss, Lawrence S. (1991), "The universal graphs of fixed finite diameter", Graph theory, combinatorics, and applications. Vol. 2 (Kalamazoo, MI, 1988), Wiley-Intersci. Publ., New York: Wiley, pp. 923–937, MR 1170834.

- Pouzet, Maurice; Sauer, Norbert (1996), "Edge partitions of the Rado graph", Combinatorica, 16 (4): 505–520, MR 1433638, doi:10.1007/BF01271269.

- Rado, Richard (1964), "Universal graphs and universal functions" (PDF), Acta Arith., 9: 331–340.

- Shelah, Saharon (1984), "On universal graphs without instances of CH", Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 26 (1): 75–87, MR 739914, doi:10.1016/0168-0072(84)90042-3.

- Shelah, Saharon (1990), "Universal graphs without instances of CH: revisited", Israel Journal of Mathematics, 70 (1): 69–81, MR 1057268, doi:10.1007/BF02807219.

- Spencer, Joel (2001), The Strange Logic of Random Graphs, Algorithms and Combinatorics, 22, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, ISBN 3-540-41654-4, MR 1847951, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04538-1.

- Truss, J. K. (1985), "The group of the countable universal graph", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 98 (2): 213–245, MR 795890, doi:10.1017/S0305004100063428.

- Vaught, Robert L. (1954), "Applications to the Löwenheim-Skolem-Tarski theorem to problems of completeness and decidability", Indagationes Mathematicae, 16: 467–472, MR 0063993.