Radical axis

The radical axis (or power line) of two circles is the locus of points at which tangents drawn to both circles have the same length. The radical axis is always a straight line and always perpendicular to the line connecting the centers of the circles, albeit closer to the circumference of the larger circle. If the circles intersect, the radical axis is the line passing through the intersection points; similarly, if the circles are tangent, the radical axis is simply the common tangent.

For any point P on the radical axis, there is a unique circle centered on P that intersects both circles at right angles (orthogonally); conversely, the center of any circle that cuts both circles orthogonally must lie on the radical axis. In technical language, each point P on the radical axis has the same power with respect to both circles[1]

where r1 and r2 are the radii of the two circles, d1 and d2 are distances from P to the centers of the two circles, and R is the radius of the unique orthogonal circle centered on P.

In general, two disjoint, non-concentric circles can be aligned with the circles of bipolar coordinates; in that case, the radical axis is simply the y-axis; every circle on that axis that passes through the two foci intersect the two circles orthogonally. Thus, two radii of such a circle are tangent to both circles, satisfying the definition of the radical axis. The collection of all circles with the same radical axis and with centers on the same line is known as a pencil of coaxal circles.

Definition and general properties

Radical center of three circles

Consider three circles A, B and C, no two of which are concentric. The radical axis theorem states that the three radical axes (for each pair of circles) intersect in one point called the radical center, or are parallel.[2] In technical language, the three radical axes are concurrent (share a common point); if they are parallel, they concur at a point of infinity.

A simple proof is as follows.[3] The radical axis of circles A and B is defined as the line along which the tangents to those circles are equal in length a=b. Similarly, the tangents to circles B and C must be equal in length on their radical axis. By the transitivity of equality, all three tangents are equal a=b=c at the intersection point r of those two radical axes. Hence, the radical axis for circles A and C must pass through the same point r, since a=c there. This common intersection point r is the radical center.

There is a unique circle with its center at the radical center that is orthogonal to all three circles. This follows, also by transitivity, because each radical axis, being the locus of centers of circles that cut each pair of given circles orthogonally, requires all three circles to have equal radius at the intersection of all three axes.

Geometric construction

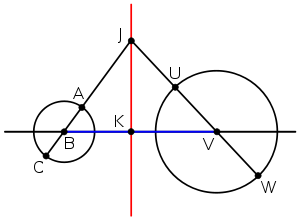

The radical axis of two circles A and B can be constructed by drawing a line through any two of its points. Such a point can be found by drawing a circle C that intersects both circles A and B in two points. The two lines passing through each pair of intersection points are the radical axes of A and C and of B and C. These two lines intersect in a point J that is the radical center of all three circles, as described above; therefore, this point also lies on the radical axis of A and B. Repeating this process with another such circle D provides a second point K. The radical axis is the line passing through both J and K.

A special case of this approach, seen in Figure 3, is carried out with antihomologous points from an internal or external center of similarity. Consider two rays emanating from an external homothetic center E. Let the antihomologous pairs of intersection points of these rays with the two given circles be denoted as P and Q, and S and T, respectively. These four points lie on a common circle that intersects the two given circles in two points each.[4] Hence, the two lines joining P and S, and Q and T intersect at the radical center of the three circles, which lies on the radical axis of the given circles.[5] Similarly, the line joining two antihomologous points on separate circles and their tangents form an isosceles triangle, with both tangents being of equal length.[6] Therefore, such tangents meet on the radical axis.[5]

Algebraic construction

Referring to Figure 4, the radical axis (red) is perpendicular to the blue line segment joining the centers B and V of the two given circles, intersecting that line segment at a point K between the two circles. Therefore, it suffices to find the distance x1 or x2 from K to B or V, respectively, where x1+x2 equals D, the distance between B and V.

Consider a point J on the radical axis, and let its distances to B and V be denoted as d1 and d2, respectively. Since J must have the same power with respect to both circles, it follows that

where r1 and r2 are the radii of the two given circles. By the Pythagorean theorem, the distances d1 and d2 can be expressed in terms of x1, x2 and L, the distance from J to K

By cancelling L2 on both sides of the equation, the equation can be written

Dividing both sides by D = x1+x2 yields the equation

Adding this equation to x1+x2 = D yields a formula for x1

Subtracting the same equation yields the corresponding formula for x2

Determinant calculation

If the circles are represented in trilinear coordinates in the usual way, then their radical center is conveniently given as a certain determinant. Specifically, let X = x : y : z denote a variable point in the plane of a triangle ABC with sidelengths a = |BC|, b = |CA|, c = |AB|, and represent the circles as follows:

- (dx + ey + fz)(ax + by + cz) + g(ayz + bzx + cxy) = 0

- (hx + iy + jz)(ax + by + cz) + k(ayz + bzx + cxy) = 0

- (lx + my + nz)(ax + by + cz) + p(ayz + bzx + cxy) = 0

Then the radical center is the point

Notes

References

- Johnson RA (1960). Advanced Euclidean Geometry: An elementary treatise on the geometry of the triangle and the circle (reprint of 1929 edition by Houghton Miflin ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 31–43. ISBN 978-0-486-46237-0.

Further reading

- Ogilvy, C. S. (1990). Excursions in Geometry. Dover. pp. 17–23. ISBN 0-486-26530-7.

- Coxeter HSM, Greitzer SL (1967). Geometry Revisited. Washington: MAA. pp. 31–36, 160–161. ISBN 978-0-88385-619-2.

- Clark Kimberling, "Triangle Centers and Central Triangles," Congressus Numerantium 129 (1998) i–xxv, 1–295.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radical axes. |