R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul

| R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Argued December 4, 1991 Decided June 22, 1992 | |

| Full case name | R.A.V., Petitioner v. City of St. Paul, Minnesota |

| Docket nos. | 90-7675 |

| Citations |

112 S. Ct. 2538; 120 L. Ed. 2d 305; 1992 U.S. LEXIS 3863; 60 U.S.L.W. 4667; 92 Cal. Daily Op. Service 5299; 92 Daily Journal DAR 8395; 6 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. S 479 |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Prior history | Statute upheld as constitutional and charges reinstated, 464 N.W.2d 507 (Minn. 1991) |

| Holding | |

| The St. Paul Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance was struck down both because it was overbroad, proscribing both "fighting words" and protected speech, and because the regulation was "content-based," proscribing only activities which conveyed messages concerning particular topics. Judgment of the Supreme Court of Minnesota reversed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

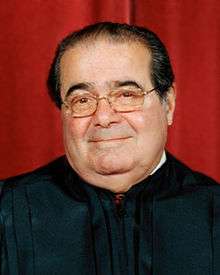

| Majority | Scalia, joined by Rehnquist, Kennedy, Souter, Thomas |

| Concurrence | White, joined by Blackmun, O'Connor; Stevens (in part) |

| Concurrence | Blackmun |

| Concurrence | Stevens, joined by White, Blackmun (in part) |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const., amend. I; St. Paul, Minn., Legis. Code § 292.02 (1990) | |

R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992) is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Supreme Court unanimously struck down St. Paul, Minnesota's Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance and reversed the conviction of a teenager, referred to in court documents only as R.A.V., for burning a cross on the lawn of an African American family for violating the First Amendment's protections for freedom of expression.

Facts and procedural background

In the early morning hours of June 21, 1990, the petitioner and several other teenagers allegedly assembled a crudely made cross by taping together broken chair legs.[1] The cross was erected and burned in the front yard of an African American family that lived across the street from the house where the petitioner was staying.[1] Petitioner, who was a juvenile at the time, was charged with two counts, one of which a violation of the St. Paul Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance.[1] The Ordinance provided:

| “ | Whoever places on public or private property, a symbol, object, appellation, characterization or graffiti, including, but not limited to, a burning cross or Nazi swastika, which one knows or has reasonable grounds to know arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender commits disorderly conduct and shall be guilty of a misdemeanor. | ” |

Petitioner moved to dismiss the count under the Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance on the ground that it was substantially overbroad and impermissibly content based, and therefore facially invalid under the First Amendment.[2] The trial court granted the motion, but the Minnesota Supreme Court reversed, rejecting petitioner's overbreadth claim because, as the Minnesota Court had construed the Ordinance in prior cases, the phrase "arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others" limited the reach of the ordinance to conduct that amounted to fighting words under the Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire decision.[3] The Minnesota Court also concluded that the ordinance was not impermissibly content based because "the ordinance is a narrowly tailored means towards accomplishing the compelling governmental interest in protecting the community against bias-motivated threats to public safety and order."[4] Petitioner appealed, and the United States Supreme Court granted certiorari.[5]

Decision

Justice Antonin Scalia delivered the opinion of the court, in which Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Justice Anthony Kennedy, Justice David Souter, and Justice Clarence Thomas joined. Justice Byron White wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment, which Justice Harry Blackmun and Justice Sandra Day O'Connor joined in full, and Justice John Paul Stevens joined in part. Justice Blackmun wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment. Justice Stevens wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment, which was joined in part by Justice White and Justice Blackmun.

The majority decision

The Court began with a recitation of the relevant factual and procedural background, noting several times that the conduct at issue could have been prosecuted under different Minnesota statutes.[6] In construing the ordinance, the Court recognized that it was bound by the construction given by the Minnesota Supreme Court.[7] Therefore, the Court accepted the Minnesota court's conclusion that the ordinance reached only those expressions that constitute "fighting words" within the meaning of Chaplinsky.

Petitioner argued that the Chaplinsky formulation should be narrowed, such that the ordinance would be invalidated as "substantially overbroad."[7] but the Court declined to consider this argument, concluding that even if all of the expression reached by the ordinance was proscribable as "fighting words," the ordinance was facially unconstitutional in that it prohibited otherwise permitted speech solely on the basis of the subjects the speech addressed.[7]

The Court began its substantive analysis with a review of the principles of free speech clause jurisprudence, beginning with the general rule that the First Amendment prevents the government from proscribing speech,[8] or even expressive conduct,[9] because of disapproval of the ideas expressed.[10] The Court noted that while content-based regulations are presumptively invalid, society has permitted restrictions upon the content of speech in a few limited areas, which are "of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that may be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality."[11]

The Court then clarified language from previous free speech clause cases, including Roth v. United States, Beauharnais v. Illinois, and Chaplinsky that suggested that certain categories of expression are "not within the area of constitutionally protected speech," and "must be taken in context."[12] The Court's clarification stated that this meant that certain areas of speech "can, consistently with the First Amendment, be regulated because of their constitutionally proscribable content (obscenity, defamation, etc.)—not that they are categories of speech entirely invisible to the Constitution, so that they may be made the vehicles for content discrimination."[13] Thus, as one of the first of a number of illustrations that Justice Scalia would use throughout the opinion, the government may "proscribe libel, but it may not make the further content discrimination of proscribing only libel critical of the government."[14]

The Court recognized that while a particular utterance of speech can be proscribed on the basis of one feature, the Constitution may prohibit proscribing it on the basis of another feature.[15] Thus, while burning a flag in violation of an ordinance against outdoor fires could be punishable, burning a flag in violation of an ordinance against dishonoring the flag is not.[15] In addition, other reasonable "time, place, or manner" restrictions were upheld, but only if they were "justified without reference to the content of the regulated speech."[16][17]

The Court recognized two final principles of free speech jurisprudence. One of these described that when "the entire basis for the content discrimination consists entirely of the very reason the entire class of speech is proscribable, no significant danger of idea or viewpoint discrimination exists." As examples, Justice Scalia wrote,

| “ | A State may choose to prohibit only that obscenity which is the most patently offensive in its prurience — i.e., that which involves the most lascivious displays of sexual activity. But it may not prohibit, for example, only that obscenity which includes offensive political messages. And the Federal Government can criminalize only those threats of violence that are directed against the President, since the reasons why threats of violence are outside the First Amendment (protecting individuals from the fear of violence, from the disruption that fear engenders, and from the possibility that the threatened violence will occur) have special force when applied to the person of the President.[18] | ” |

The other principle of free speech jurisprudence was recognized when the Court wrote that a valid basis for according different treatment to a content-defined subclass of proscribable speech is that the subclass "happens to be associated with particular 'secondary effects' of the speech, so that 'the regulation is justified without reference to the content of the … speech'"[19] As an example, the Court wrote that a State could permit all obscene live performances except those involving minors.[20]

Applying these principles to the St. Paul Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance, the Court concluded that the ordinance was facially unconstitutional. Justice Scalia explained the rationale, writing,

| “ | Although the phrase in the ordinance, "arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others," has been limited by the Minnesota Supreme Court's construction to reach only those symbols or displays that amount to "fighting words," the remaining, unmodified terms make clear that the ordinance applies only to "fighting words" that insult, or provoke violence, "on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender." Displays containing abusive invective, no matter how vicious or severe, are permissible unless they are addressed to one of the specified disfavored topics. Those who wish to use "fighting words" in connection with other ideas—to express hostility, for example, on the basis of political affiliation, union membership, or homosexuality—are not covered. The First Amendment does not permit St. Paul to impose special prohibitions on those speakers who express views on disfavored subjects.[21] | ” |

The Court went on to explain that, in addition to being an impermissible restriction based on content, the Ordinance was also viewpoint- based discrimination, writing,[21]

| “ | As explained earlier, see supra, at 386, the reason why fighting words are categorically excluded from the protection of the First Amendment is not that their content communicates any particular idea, but that their content embodies a particularly intolerable (and socially unnecessary) mode of expressing whatever idea the speaker wishes to convey. St. Paul has not singled out an especially offensive mode of expression—it has not, for example, selected for prohibition only those fighting words that communicate ideas in a threatening (as opposed to a merely obnoxious) manner. Rather, it has proscribed fighting words of whatever manner that communicate messages of racial, gender, or religious intolerance. Selectivity of this sort creates the possibility that the city is seeking to handicap the expression of particular ideas. That possibility would alone be enough to render the ordinance presumptively invalid, but St. Paul’s comments and concessions in this case elevate the possibility to a certainty. | ” |

Displays containing some words, such as racial slurs, would be prohibited to proponents of all views, whereas fighting words that "do not themselves invoke race, color, creed, religion, or gender—aspersions upon a person's mother, for example—would seemingly be usable ad libitum in the placards of those arguing in favor of racial, color, etc., tolerance and equality, but could not be used by those speakers' opponents."[21] The Court concluded that "St. Paul has no such authority to license one side of a debate to fight freestyle, while requiring the other to follow Marquess of Queensberry rules."[21]

The Court concluded, "Let there be no mistake about our belief that burning a cross in someone's front yard is reprehensible. But St. Paul has sufficient means at its disposal to prevent such behavior without adding the First Amendment to the fire."[22]

Limitation

In Virginia v. Black (2003), the United States Supreme Court deemed constitutional the part of a Virginia statute outlawing the public burning of a cross with intent to intimidate, but held that statutes not requiring additional showing of intent to intimidate (other than the cross itself) were unconstitutional. It concluded that cross burning done with an intent to intimidate can be criminalized, because such expression has a long and pernicious history as a signal of impending violence.

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 505

- List of United States Supreme Court cases

- Lists of United States Supreme Court cases by volume

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Rehnquist Court

References

- 1 2 3 505 U.S. 379 (1992)

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 380

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 380-381

- ↑ In re Welfare of R.A.V., 464 N.W.2d 507, 510 (Minn. 1991)

- ↑ 501 U.S. 1204 (1991)

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 379–380, N.1

- 1 2 3 505 U.S. at 381

- ↑ Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940)

- ↑ Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989)

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 382

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 382–383, citing Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 383

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 383-384, emphasis in original

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 384

- 1 2 505 U.S. at 385

- ↑ Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781 (1989)

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 386

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 388, internal citations omitted (emphasis in original)

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 389, quoting Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc., 475 U.S. 41 (1986) (emphasis in original)

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 389

- 1 2 3 4 505 U.S. at 391

- ↑ 505 U.S. at 396

Further reading

- Amar, Akhil Reed (1992). "The Case of the Missing Amendments: R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul". Faculty Scholarship Series (Paper 1039): 124–61.

- Butler, Judith (1997). Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-91588-0.

- Crowley, Andrea L. (1993). "R.A.V v. City of St. Paul: How the Supreme Court Missed the Writing on the Wall". Boston College Law Review. 34 (4): 771–801.

- Kagan, Elena (1992). "The Changing Faces of First Amendment Neutrality: R.A.V. v St. Paul, Rust v Sullivan, and the Problem of Content-Based Underinclusion". The Supreme Court Review. 1992 (1992): 29–77. JSTOR 3109667.

- Levin, Brian (2002). "From Slavery to Hate Crime Laws: The Emergence of Race and Status-Based Protection in American Criminal Law". Journal of Social Issues. 58 (2): 227–45. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.00258.

- Matsuda, Mari J.; Lawrence, Charles R.; Delgado, Richard; Crenshaw, Kimberle W. (1993). Words That Wound: Critical Race Theory, Assaultive Speech, and the First Amendment. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8428-1.

- Sumner, L.W. (2005), "Hate crimes, literature, and speech", in Frey, R.G.; Heath Wellman, Christopher, A companion to applied ethics, Blackwell Companions to Philosophy, Oxford, UK Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 89–101, ISBN 9781405133456, doi:10.1002/9780470996621.ch11.

External links

- Text of R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992) is available from: Findlaw Justia

- First Amendment Library entry on R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul

- Oral Argument Audio on Oyez

- Full Text of Volume 505 of the United States Reports at www.supremecourt.gov