Qutbism

| Part of a series on |

| Jihadism |

|---|

|

| Islamic fundamentalism |

| Notable jihadist organisations |

| Jihadism in the East |

| Jihadism in the West |

|

|

Qutbism (also called Kotebism, Qutbiyya, or Qutbiyyah) is an Islamist ideology developed by Sayyid Qutb, the figurehead of the Muslim Brotherhood.[1] It has been described as advancing the extremist jihadist ideology of propagating "offensive jihad" – waging jihad in conquest[2] – or "armed jihad in the advance of Islam" [3]

Qutbism has gained widespread attention because it is widely believed to have influenced Islamic extremists and terrorists such as Osama bin-Laden. Muslim extremists “cite Sayyid Qutb repeatedly and consider themselves his intellectual descendants.”[3]

Tenets

The main tenet of Qutbist ideology is that the Muslim community (or the Muslim community outside of a vanguard fighting to reestablish it) "has been extinct for a few centuries"[4] having reverted to Godless ignorance (Jahiliyya), and must be reconquered for Islam.[5]

Qutb outlined his ideas in his book Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq (aka Milestones). Other important principles of Qutbism include:

- Adherence to Sharia as sacred law accessible to humans, without which Islam cannot exist

- Adherence to Sharia as a complete way of life that will bring not only justice, but peace, personal serenity, scientific discovery, complete freedom from servitude, and other benefits

- Avoidance of Western and non-Islamic "evil and corruption," including socialism, nationalism and consumerist capitalism[6]

- Vigilance against Western and Jewish conspiracies against Islam

- A two-pronged attack of 1) preaching to convert and 2) jihad to forcibly eliminate the "structures" of Jahiliyya[7]

- The importance of offensive Jihad to eliminate Jahiliyya not only from the Islamic homeland but from the face of the Earth

Spread of Qutb's ideas

Qutb's message was spread through his writing, his followers and especially through his brother, Muhammad Qutb, who moved to Saudi Arabia following his release from prison in Egypt and became a professor of Islamic Studies and edited, published and promoted his brother Sayyid's work.[8][9]

Ayman Al-Zawahiri, who went on to become a member of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, was one of Muhammad Qutb's students [10] and later a mentor of Osama bin Laden and a leading member of al-Qaeda.[11] and had been first introduced to Sayyad Qutb by his uncle, Mafouz Azzam, who had been very close to Sayyad Qutb throughout his life and impressed on al-Zawahiri "the purity of Qutb's character and the torment he had endured in prison."[12] Zawahiri paid homage to Qutb in his work Knights under the Prophet's Banner.[13]

Osama bin Laden is reported to have regularly attended weekly public lectures by Muhammad Qutb, at King Abdulaziz University, and to have read and been deeply influenced by Sayyid Qutb.[14]

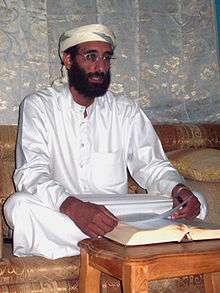

Late Yemeni Al Qaeda leader Anwar al-Awlaki has also spoken of Qutb's great influence and of being "so immersed with the author I would feel Sayyid was with me... speaking to me directly.”[15]

History of the word "Qutbee"

Following Qutb's death Qutbist ideas spread throughout Egypt and other parts of the Arab and Muslim world, prompting a backlash by more traditionalist and conservative Muslims, such as the book Du'ah, la Qudah (Preachers, not Judges) (1969). The book, written by MB Supreme Guide Hassan al-Hudaybi, attacked the idea of Takfir of other Muslims (but was ostensibly targeted not at Qutb but at Mawdudi, as al-Hudaybi had been a friend and supporter of Qutb).[16]

Like the term "Wahhabi", Qutbee is used not by the alleged Qutbees to describes themselves, but by their critics.[17]

Takfir

The most controversial aspect of Qutbism is takfir, Qutb's idea that Islam is "extinct." According to takfir, with the exception of Qutb’s Islamic vanguard, those who call themselves Muslims are not actually Muslim. Takfir was intended to shock Muslims into religious re-armament. When taken literally, takfir also had the effect of causing non-Qutbists who claimed to be Muslim in violation of Sharia law, a law that Qutb very much supported. Violating this law could potentially be considered apostasy from Islam: a crime punishable by death according to Qutbis.[18]

Because of these serious consequences, Muslims have traditionally been reluctant to practice takfir, that is, to pronounce professed Muslims as unbelievers (even Muslims in violation of Islamic law).[19] This prospect of fitna, or internal strife, between Qutbists and "takfir-ed" mainstream Muslims, was put to Qutb by prosecutors in the trial that led to his execution,[20] and is still made by his Muslim detractors.[21][22]

Qutb died before he could clear up the issue of whether jahiliyyah referred to the whole "Muslim world," to only Muslim governments, or only in an allegorical sense,[23] but a serious campaign of terror – or "physical power and jihad" against "the organizations and authorities" of "jahili" Egypt – by insurgents observers believed to be influenced by Qutb followed in the 1980s and 1990s.[24] Victims included Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, head of the counter-terrorism police Major General Raouf Khayrat, parliamentary speaker Rifaat el-Mahgoub, dozens of European tourists and Egyptian bystanders, and over one hundred Egyptian police officers.[25] Other factors (such as economic dislocation/stagnation and rage over President Sadat's policy of reconciliation with Israel) played a part in instigating the violence,[26] but Qutb's takfir against jahiliyyah (or jahili) society, and his passionate belief that jahiliyyah government was irredeemably evil, played a key role.[27]

Muslim criticism

While Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq [Arabic: معالم في الطريق] (Milestones) was Qutb's manifesto, other elements of Qutbism are found in his works Al-'adala al-Ijtima'iyya fi-l-Islam [Arabic: العدالة الاجتماعية في الاسلام] (Social Justice in Islam), and his Quranic commentary Fi Zilal al-Qur'an [Arabic: في ظلال القرآن] (In the shade of the Qur'an). Ideas in (or alleged to be in) those works also have come under attack from both traditionalist/conservative Muslims and Salafi/Wahhabi Muslims. They include:

- Qutb's assertion that slavery is now illegal under Islam, as its lawfulness was only temporary, existing only "until the world devised a new code of practice, other than enslavement." Salafist critics maintain "Islaam has affirmed slavery ... And it will continue so long as Jihaad in the path of Allaah exists." (Shaikh Salih al-Fawzaan)[28] Most contemporary Islamic scholars, however, do share the view that slavery is not allowed in Islam in modern times. [29]

- Proposals to redistribute income and property to the needy. Opponents claim they are "socialist" and innovations of Islam.[30][31][32]

- Describing Moses as having an "excitable nature" – this allegedly being "mockery," and "mockery of the Prophets is apostasy in its own,'" according to Shaikh ‘Abdul-Azeez Ibn Baz.

- Dismissing fiqh or the schools of Islamic law known as madhhab as separate from "Islamic principles and Islamic understanding."[33]

- Desiring to unite the four schools of Islamic law into one school – allegedly an innovation.[34]

- Favoring the overthrow of tyrants, when Islam teaches that "when you cannot correct a wrong thing be patient! Allah ... will correct it."[21]

Accusations against Qutbism include some that may contradict what Qutb actually said, such as one alleging that Qutb believed "Christians should be left as Christians – Jews as Jews," since he believed in hurriyatul-i'tiqaad (freedom of belief).[35]

Qutb may now be facing criticism representing his idea's success or Qutbism's logical conclusion as much as his idea's failure to persuade some critics. Writing before the Islamic revival was in full bloom, Qutb sought Islamically-correct alternatives to European ideas like Marxism and socialism and proposed Islamic means to achieve the ends of social justice and equality, redistribution of private property, political revolution. But according to Olivier Roy, contemporary "neofundamentalist refuse to express their views in modern terms borrowed from the West. They consider indulging in politics, even for a good cause, will by definition lead to bid'a and shirk (the giving of priority to worldly considerations over religious values.)"[36]

There are, however, some commentators who display an ambivalence towards him, and Roy notes that "his books are found everywhere and mentioned on most neo-fundamentalist websites, and arguing his "mystical approach", "radical contempt and hatred for the West", and "pessimistic views on the modern world" have resonated with these Muslims.[37]

Science and learning

On the importance of science and learning, the key to the power of his bête noire, western civilization, Qutb was ambivalent. He wrote that

Muslims have drifted away from their religion and their way of life, and have forgotten that Islam appointed them as representatives of God and made them responsible for learning all the sciences and developing various capabilities to fulfill this high position which God has granted them.

... and encouraged Muslims to seek knowledge.

A Muslim can go to a Muslim or to a non-Muslim to learn abstract sciences such as chemistry, physics, biology, astronomy, medicine, industry, agriculture, administration (limited to its technical aspects), technology, military arts and similar sciences and arts; although the fundamental principle is that when the Muslim community comes into existence it should provide experts in all these fields in abundance, as all these sciences and arts are a sufficient obligation (Fard al-Kifayah) on Muslims (that is to say, there ought to be a sufficient number of people who specialize in these various sciences and arts to satisfy the needs of the community). (Qutb, Milestones p. 109)

On the other hand, Qutb believed some learning was forbidden to Muslims and should not be studied, including:

principles of economics and political affairs and interpretation of historical processes... origin of the universe, the origin of the life of man... philosophy, comparative religion... sociology (excluding statistics and observations)... Darwinist biology ([which] goes beyond the scope of its observations, without any rhyme or reason and only for the sake of expressing an opinion...). (Qutb, Milestones pp. 108–10)

and that the era of scientific discovery (that non-Muslim Westerners were so famous for) was now over:

The period of resurgence of science has also come to an end. This period, which began with the Renaissance in the sixteenth century after Christ and reached its zenith in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, does not possess a reviving spirit. [Qutb, Milestones p. 8]

However important scientific discovery was, or is, an important tool to achieve it (and to do everything else) is to follow Sharia law under which

blessings fall on all mankind, [and] leads in an easy manner to the knowledge of the secrets of nature, its hidden forces and the treasures concealed in the expanses of the universe. [Qutb, Milestones p. 90]

Qutbism and non-Muslims

| Part of a series on:

Salafi movement |

|---|

Sab'u Masajid, Saudi Arabia |

|

|

Other elements of Qutbism deal with non-Muslims, particularly Westerners, and have drawn attention and controversy from their subjects, particularly following the September 11, 2001 attacks. Though their terminology, issues and arguments are different from those of the Islamic traditionalists, Westerners also have criticism to make.

Islamic law and freedom

Qutbism postulates that sharia-based society will have an almost supernatural perfection, providing justice, prosperity, peace and harmony both individually and societally.

Its wonders are such that the use of offensive jihad to spread sharia-Islam throughout the non-Muslim world will not be aggression but "a movement... to introduce true freedom to mankind." It frees humanity from servitude to man because its divine nature requires no human authorities to judge or enforce its law.

Vigilance against conspiracies

Qutbism emphasizes what it sees as evil designs of Westerners and Jews against Islam, and the importance of Muslims not trusting or imitating them.

The West

In Qutb's view, for example, Western Imperialism is not, as Westerners would have Muslims believe, only an economic exploitation of weak peoples by the strong and greedy.[38] Nor were the medieval Crusades, as some historians claim, merely an attempt by Christians to reconquer the formerly Christian-ruled, Christian holy land; some historians have disagreed because the crusaders slaughtered Arab Christians too.

Both were different expressions of the West's "pronounced... enmity" towards Islam, including plans to "demolish the structure of Muslim society." [39] Imperialism is "a mask for the crusading spirit." [40]

Examples of Western malevolence Qutb personally experienced and related to his readers include an attempt by a "drunken, semi-naked... American agent" to seduce him on his voyage to America, and the (alleged) celebration of American hospital employees upon hearing of the assassination of Egyptian Ikhwan Supreme Guide Hasan al-Banna.[41]

Qutb's Western critics have questioned whether Qutb was likely to arouse interest of American intelligence agents (as he was not a member of the Egyptian government or any political organization at that time), or whether many Americans, let alone hospital employees, knew who Hasan al-Banna or the Muslim Brotherhood were in 1948.[42]

Jews

The other anti-Islamic conspirator group, according to Qutb, is "World Jewry," which he believes is engaged in tricks to eliminate "faith and religion", and trying to divert "the wealth of mankind" into "Jewish financial institutions" by charging interest on loans.[43] Jewish designs are so pernicious, according to Qutb's logic, that "anyone who leads this [Islamic] community away from its religion and its Quran can only be [a] Jewish agent", causing one critic to claim that the statement apparently means that "any source of division, anyone who undermines the relationship between Muslims and their faith is by definition a Jew".[44]

Western corruption

Qutbism emphasizes a claimed Islamic moral superiority over the West, according to Islamist values. One example of "the filth" and "rubbish heap of the West" (Qutb, Milestones, p. 139) was the "animal-like" "mixing of the sexes." Qutb states that while he was in America a young woman told him

The issue of sexual relations is purely a biological matter. You... complicate this matter by imposing the ethical element on it. The horse and mare, the bull and the cow... do not think about this ethical matter... and, therefore, live a comfortable, simple, and easy life.[45]

Critics complain that this opinion was wildly unrepresentative and the incident highly improbable. Even at the height of the sexual revolution in America 30 years later, most Americans would disagree with his statement, but at the time of his visit to America, sex out of wedlock, let alone "animal-like" promiscuity, was rare, with the overwhelming number of Americans married as virgins or that only had premarital sex with their future spouse.[46]

Muslim Brotherhood

Controversy over Qutbism is in part an expression of the disagreement of two of the main tendencies of the Islamic revival: the more quiest Salafi Muslims, and the more radically active Muslim groups associated with the Muslim Brotherhood,[47] the group Qutb was a member of for about the last decade and a half of his life.

Although Sayyid Qutb was never head (or "Supreme Guide") of the Muslim Brotherhood,[48] he was the Brotherhood's "leading intellectual," [49] editor of its weekly periodical, and a member of the highest branch in the Brotherhood, the Working Committee and of the Guidance Council.[50]

After the publication of Ma'alim fi-l-Tariq, (Milestones), opinion in the Brotherhood split over his ideas, though many in Egypt (including radicals outside the Brotherhood) and most Brethren in other countries are said to have shared his analysis "to one degree or another."[51] In recent years his ideas have been embraced by radical Islamists groups[52] while the Muslim Brotherhood has tended to serve as the official voice of Islamist moderation.

References

- ↑ Qutbism Earthlysojourner.com

- ↑ DouglasFarah.com, Qutbism and the Muslim Brotherhood by Douglas Farah

- 1 2 William McCants of the US Military Academy’s Combating Terrorism Center, quoted in Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism by Dale C. Eikmeier. From Parameters, Spring 2007, pp. 85–98.

- ↑ Qutb, Sayyid, Milestones, The Mother Mosque Foundation, 1981, p. 9

- ↑ Muslim extremism in Egypt: the prophet and pharaoh by Gilles Kepel, p. 46

- ↑ "Muslim Extremism in Egypt". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Muslim extremism in Egypt: the prophet and pharaoh by Gilles Kepel, p. 55–6

- ↑ Kepel, War for Muslim Minds, (2004) pp. 174–75

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, (2002), p. 51

- ↑ Sageman, Marc, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, p. 63

- ↑ "How Did Sayyid Qutb Influence Osama bin Laden?". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Wright, Looming Tower, 2006, p. 36

- ↑ "Sayyid_Qutbs_Milestones". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Wright, Looming Tower, 2006, p. 79

- ↑ Scott Shane; Souad Mekhennet & Robert F. Worth (8 May 2010). "Imam’s Path From Condemning Terror to Preaching Jihad". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ↑ Sayyid Qutb and the Origins of Radical Islamism by John Calvert, p. 274

- ↑ Pioneers of Islamic revival by ʻAlī Rāhnamā, p. 175

- ↑ Eikmeier, DC (Spring 2007). Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism. 37. Parameters, US Army War College Quarterly,. p. 89.

In addition to offensive jihad Sayyid Qutb used the Islamic concept of “takfir” or excommunication of apostates. Declaring someone takfir provided a legal loophole around the prohibition of killing another Muslim and in fact made it a religious obligation to execute the apostate. The obvious use of this concept was to declare secular rulers, officials or organizations, or any Muslims that opposed the Islamist agenda a takfir thereby justifying assassinations and attacks against them. Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, who was later convicted in the 1993 World Trade Center attack, invoked Qutb’s takfirist writings during his trial for the assassination of President Anwar Sadat. The takfir concept along with “offensive jihad” became a blank check for any Islamic extremist to justify attacks against anyone.

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, p. 31

- ↑ Sivan, Radical Islam, (1985), p. 93

- 1 2 "Hakikat Kitabevi". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "The Wahhabi Myth – Salafism, Wahhabism, Qutbism. Who was Sayyid Qutb? (part 2)". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, 2002, p. 31

- ↑ Sayyid Qutb and the Origins of Radical Islamism by John Calvert, p. 285

- ↑ Passion for Islam: Shaping the Modern Middle East: The Egyptian Experience by Caryle Murphy, p. 91

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, 2002, p. 31,

Ruthven, Malise, Islam in the World, Penguin Books, 1984, pp. 314–15 - ↑ Kepel, The Prophet and Pharaoh, pp. 65, 74–5, Understanding Jihad by David Cook, University of California Press, 2005, p. 139

- ↑ see also: Shaikh Salih al-Fawzaan "affirmation of slavery" p. 24 of "Taming a Neo-Qutubite Fanatic Part 1" when accessed on February 17, 2007

- ↑ [T]the al-Azhar Islamic Research Centre issued a statement asserting that “melk al-yameen” is a form of marriage affiliated to the system of slavery that existed in the world during the early days of Islam, and Islam gradually clamped down on this system in terms of legislation. The statement stressed that Islam sought to end all forms of slavery. Dr. Ali Abdul Baqi, head of the al-Azhar Islamic Research Centre, stressed that “international laws and charters have been issued prohibiting slavery and enshrining human freedom, and so ‘melk al-yameen’ has ended, and it is no longer present and will not return.” He added “talking about ‘melk al-yameen’ now represents a return to the era of jahiliyyah and an invitation to forbidden and sinful sexual relations...” Asharq Alaswat | Egypt: “Slavery marriage” case sparks controversy | http://english.aawsat.com/theaawsat/features/egypt-slavery-marriage-case-sparks-controversy

- ↑ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Hakikat Kitabevi". Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ Qutb argued that under true Islam non-Muslims could "accept [Islam] or not" (Milestones, p. 61), but never said they should be "left" as non-Muslims.

- ↑ Roy, Globalized Islam, (2004), p. 247

- ↑ Roy, Globalized Islam, (2004), p. 250

- ↑ Qutb, Milestones, Chapter 12

- ↑ Qutb, Milestones, p. 116

- ↑ Qutb, Milestones, pp. 159–60

- ↑ Wright, The Looming Tower, 2006

- ↑ Soufan Ali, The Black Banners, October 2008

- ↑ The age of sacred terror, Daniel Benjamin, Steven Simon, p. 68

- ↑ quote from David Zeidan, "The Islamic Fundamentalist View of Life as Perennial Battle," Middle East Review of International Affairs, v. 5, n. 4 (December 2001), criticism from The Age of Sacred Terror by Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon, Random House, 2002, p. 68

- ↑ from Amrika allati Ra'aytu, (America that I Saw), quoted in Radical Islamic Fundamentalism: the Ideological and Political Discourse of Sayyid Qutb by Ahmad S. Moussalli, American University of Beirut, 1992, p. 29

- ↑ For example, over 80% of the women surveyed who were born between 1933 and 1942 either had no premarital intercourse or premarital intercourse only with their future husband, according to the National Health and Social Life Survey. (Robert T. Michael, John H. Gagnon, Edward O. Laumann, Gina Kolata, Sex in America : A definitive Survey, Little Brown and Co., 1994, p. 97)

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles, The War for Muslim Minds, 2004, p.253-266

- ↑ Hasan al-Hudaybi was Supreme Guide during this period.

- ↑ Ruthvan, Malise, Islam in the World, Penguin, 1984

- ↑ Moussalli, Radical Islamic Fundamentalism, 1992, p.31-2

- ↑ Hamid Algar from his introduction to Social Justice in Islam by Sayyid Qutb, translated by John Hardie, translation revised and introduction by Hamid Algar, Islamic Publications International, 2000, p.1, 9, 11

- ↑ William McCants, a Bahai consultant, quoted in Qutbism: An Ideology of Islamic-Fascism by Dale C. Eikmeier From Parameters, Spring 2007, pp. 85-98.

Bibliography

- Kepel, Gilles (1985). The Prophet and Pharaoh: Muslim Extremism in Egypt. translated by Jon Rothschild. Al Saqi. ISBN 0-86356-118-7.

- Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad, The Trail of Political Islam. translated by Anthony F. Roberts. Belknap Press of Harvard University. ISBN 0-674-00877-4.

- Moussalli, Ahmad S. (1992). Radical Islamic Fundamentalism: the Ideological and Political Discourse of Sayyid Qutb. American University of Beirut.

- Qutb, Sayyid (2003). Milestones. Kazi Publications. ISBN 1-56744-494-6.

- Roy, Olivier (2004). Globalized Islam: the Search for a New Ummah. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13498-3.

- Sivan, Emmanuel (1985). Radical Islam: Medieval Theology and Modern Politics. Yale University Press.

Further reading

- Berman, Paul. Terror and Liberalism. W. W. Norton & Company, April 2003.

- Berman devotes several chapters of this work to discussing Qutb as the foundation of a unique strain of Islamist thought.

- Malik, S. K. (1986). The Quranic Concept of War (PDF). Himalayan Books. ISBN 81-7002-020-4.

- Swarup, Ram (1982). Understanding Islam through Hadis. Voice of Dharma. ISBN 0-682-49948-X.

- Trifkovic, Serge (2006). Defeating Jihad. Regina Orthodox Press, USA. ISBN 1-928653-26-X.

- Phillips, Melanie (2006). Londonistan: How Britain is Creating a Terror State Within. Encounter books. ISBN 1-59403-144-4.

External links

- Stanley, Trevor Sayyid Qutb, The Pole Star of Egyptian Salafism.

- El-Kadi, Ahmed Great Muslims of the 20th Century ... Sayyid Qutb.

- Who was Sayyid Qutb?

- Reformer Qutb Thinks Himself Superior to Madhhab Imams.

- Reformer Qutb Invites People to Stand Up and Shout Against the Dictators.

- Mawdudi, Qutb and the Prophets of Allah.

- The Ideology of Terrorism and Violence in Saudi Arabia: Origins, Reasons and Solution