Quiggly hole

A quiggly hole, also known as a pit-house or simply as a quiggly or kekuli, is the remains of an earth lodge built by the First Nations people of the Interior of British Columbia and the Columbia Plateau in the U.S.. The word quiggly comes from kick willy or keekwulee, the Chinook Jargon word for "beneath" or "under".

Appearance and location

Quigglies appear as a circular depression in the ground which are the remnants of former log-roofed pithouses. Quigglies generally come in large groupings known as quiggly towns, some with hundreds of holes indicating a potential population of thousands. Some of these holes were residential for single family or larger groups, while some may have been storage only. Quiggly towns are typically located where solar exposure, water supply, and access to fish, game and gatherable foodstuffs are favorable.

Quiggly towns and smaller groups of quiggly holes are common features of the landscape in certain areas of southern British Columbia, notably from the Fraser Canyon near Lillooet across the Thompson River valley and down the Okanagan Valley.

Hudson's Bay Flats is the old location of a site called Fort Chilcotin. The Fort Chilcotin site contains a number of quiggly holes.[1] The Thompson river between Pritchard and Kamloops also has quiggly holes.[2] Indian artifacts have been recovered from quiggly holes including arrowheads and scrapers. Some rockhounds believe digging around quiggly holes looking for artifacts destroys what little historical record remains.[3]

Archaeological site

One of the most famous "quiggly towns" in the Fraser Canyon is the Keatley Creek Archaeological Site, between the modern-day First Nations communities at Fountain and Pavilion and home of over 115 quiggly holes. It has been the subject of formal archaeological investigation. Diggings have shown its origins to have been between 4,800 BCE and 2,400 BCE, with ongoing habitation up to 1,100 BCE. The reason for the abandonment is believed to have been the collapse of a slide which had blocked the Fraser River, forming a lake reaching upstream many miles, such that the location at Keatley Creek was near the shoreline (it is today on a benchland high above the river's canyon).

Description

This type of structure was used for storage as well as housing and cooking, and may have had its origins as an expansion of the concept of a root cellar. In their most elaborate form, a deep pit is covered by a dome made out of a log frame, then covered by earth. Usually entrance is made either by a side hole, or a ladder via the fire hole in the top. Today the word quiggly usually only means the archaeological remains, not an active underground house, if one is being spoken of in a story or a history.

Similar structures are used in the sweat lodges that are common in First Nations communities today, though those are made out of sticks instead of logs, with branches and blankets instead of earth as a covering. As with sweat lodges, some quiggly holes were once undoubtedly used for ritual and community as well.

Range of use

Although found to a limited degree on the southern British Columbia Coast and Puget Sound where log-frame longhouses and lean-to structures are more common, they are the main trait of native pre-Contact archaeology throughout the Interior cultures, and may have variously been either seasonal or permanent settlements. Replacement of quigglies with modern-style housing in the Interior only began in the late 19th century, with individual holdouts of active underground house living into the mid-20th century. Efforts to resettle Interior Plateau First Nations in log-cabin villages – "modern" housing in the 19th century, relatively speaking – were launched by the Oblate Fathers as part of their missionary work.

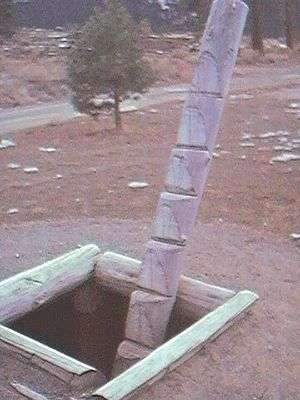

A reconstruction

A reconstruction of an underground house can be seen by the public near the Lillooet Tribal Council's offices near the reserve community of T't'ikt (in English the "T-bird Rancherie") in Lillooet, British Columbia. Called a si7xten (SHIH-stn) in the St'at'imcets language, its design is based on notes drawn by anthropologist James Teit, who had settled and married in with the Nlaka'pamux people of Spences Bridge. Teit had never been to Lillooet and based all his knowledge of the si7xten and the rest of his notes on that people, but based all his knowledge on interviews with a St'at'imc woman who had married into the Spences Bridge people. It was not just from her account that Teit drew drawings upon which Lillooet's rebuilt si7xten was built, but also from his knowledge of underground houses in the Thompson and Bonaparte valleys – in his day, many people still lived in them. The reconstruction proceeded with his designs, with the caveat that the si7xten as built may not exactly resemble those used by the St'at'imc, as those with the knowledge of how they were built died years before there was interest in restoring one.

Quiggly towns are important landmarks in the broader context of First Nations land claims, where they are more than symbols of native occupancy: they are the proof of ownership, as well as a priori occupation rights including sovereignty. Inventories of quigglies and other archaeological remains are important parts of the land claims process and archaeological protection acts may be invoked to preserve and study them. Quigglies are protected under the British Columbia Heritage Conservation Act, on both public and private lands.[4]

Although many quiggly towns are relatively new, up to a few hundred years, many more are very ancient, as at Keatley Creek, but also throughout the Interior. And in addition to the Plateau cultures, there is an isolated appearance of quiggly-type structures on the Oregon Coast, in what is otherwise exclusively log-frame/housepost housing area. Its occupants are believed by archaeologists to have been ancestors of the Athapaskan people resident in the area now, who had originally used their familiar style of housing when they first migrated into the region.

See also

References

- ↑ Lazeo, Lawerence A. (1975), Collector's Guide To BC Indian Artifact Sites.

- ↑ Pearsons, Howard L., BC Gem Trails 3rd addition with maps.

- ↑ Hudson Rick (1999), A Field Guide To Gold, Gemstone and Mineral Sites of British Columbia. Volume 2. Orca Book Publishers.

- ↑ Heritage Conservation Act