Quercus alba

| White oak | |

|---|---|

| |

| A large white oak in New Jersey | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Quercus |

| Section: | Quercus |

| Species: | Q. alba |

| Binomial name | |

| Quercus alba L. 1753 | |

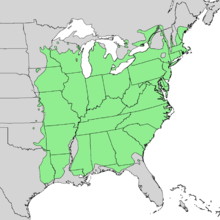

| |

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Quercus alba, the white oak, is one of the preeminent hardwoods of eastern and central North America. It is a long-lived oak, native to eastern and central North America and found from Minnesota, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia south as far as northern Florida and eastern Texas.[3] Specimens have been documented to be over 450 years old.[4]

Although called a white oak, it is very unusual to find an individual specimen with white bark; the usual color is a light gray. The name comes from the color of the finished wood. In the forest it can reach a magnificent height and in the open it develops into a massive broad-topped tree with large branches striking out at wide angles.[5]

Description

Q. alba typically reaches heights of 80 to 100 feet (24–30 m) at maturity, and its canopy can become quite massive as its lower branches are apt to extend far out laterally, parallel to the ground. Trees growing in a forest will become much taller than ones in an open area which develop to be short and massive. The tallest known white oak is 144 feet (44 m) tall. It is not unusual for a white oak tree to be as wide as it is tall, but specimens growing at high altitudes may only become small shrubs.

White oak may live 200 to 300 years, with some even older specimens known. The Wye Oak in Wye Mills, Maryland was estimated to be over 450 years old when it finally fell in a thunderstorm in 2002.[6]

Another noted white oak is the Great White Oak in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, estimated to be over 600 years old. The tree measures 25 feet (7.6 m) in circumference at the base and 16 feet (4.9 m) in circumference four feet (1.2 m) above the ground. The tree is 75 feet (23 m) tall, and its branches spread over 125 feet (38 m) from tip to tip.[7] The oak, claimed to be the oldest in the United States, began showing signs of poor health in the mid-2010s.[8] The tree was declared dead in 2016 and was planned to be taken down in 2017.[9]

Sexual maturity begins at around 20 years, but the tree does not produce large crops of acorns until its 50th year and the amount varies from year to year. Acorns deteriorate quickly after ripening, the germination rate being only 10% for six-month-old seeds. As the acorns are prime food for animals and insects, all may be lost in years of small crops.[10]

The bark is a light ash-gray and peels somewhat from the top, bottom and/or sides.[11]

In spring the young leaves are of a delicate, silvery pink and covered with a soft, blanket-like down. The petioles are short, and the leaves which cluster close to the ends of the shoots are pale green and downy with the result that the entire tree has a misty, frosty look. This condition continues for several days, passing through the opalescent changes of soft pink, silvery white and finally yellow green.[5][11]

The leaves grow to be 5 to 8.5 inches (13–22 cm) long and 2.75 to 4.5 inches (7.0–11.4 cm) wide and have a deep glossy green upper surface. They usually turn red or brown in autumn, but depending on climate, site, and individual tree genetics, some trees are nearly always red, or even purple in autumn. Some brown, dead leaves may remain on the tree throughout winter until very early spring. The lobes can be shallow, extending less than halfway to the midrib, or deep and somewhat branching.

The acorns are usually sessile, and grow to 0.5 to 1 inch (13–25 mm) in length, falling in early October.

Quercus alba is sometimes confused with the swamp white oak, a closely related species, and the bur oak. The white oak hybridizes freely with the bur oak, the post oak, and the chestnut oak.[5]

- Bark: Light gray, varying to dark gray and to white; shallow fissured and scaly. Branchlets at first bright green, later reddish-green and finally light gray. A distinguishing feature of this tree is that a little over halfway up the trunk the bark tends to form overlapping scales that are easily noticed and aid in identification.[11]

- Wood: Light brown with paler sapwood; strong, tough, heavy, fine-grained and durable. Specific gravity, 0.7470; weight of one cubic foot, 46.35 lbs; weight of one cubic meter 770 kg.[11][12]

- Winter buds: Reddish brown, obtuse, one-eighth of an inch long.[11]

- Leaves: Alternate, five to nine inches long, three to four inches wide. Obovate or oblong, seven to nine-lobed, usually seven-lobed with rounded lobes and rounded sinuses; lobes destitute of bristles; sinuses sometimes deep, sometimes shallow. On young trees the leaves are often repand. They come out of the bud conduplicate, are bright red above, pale below, and covered with white tomentum; the red fades quickly and they become silvery greenish white and shiny; when full grown they are thin, bright yellow green, shiny or dull above, pale, glaucous or smooth below; the midrib is stout and yellow, primary veins are conspicuous. In late autumn the leaves turn a deep red and drop, or on young trees remain on the branches throughout the winter. Petioles are short, stout, grooved, and flattened. Stipules are linear and caducous.[11]

- Flowers: appear in May, when leaves are one-third grown. Staminate flowers are borne in hairy aments two and a half to three inches long; the calyx is bright yellow, hairy, six to eight-lobed, with lobes shorter than the stamens; anthers are yellow. Pistillate flowers are borne on short peduncles; involucral scales are hairy, reddish; calyx lobes are acute; stigmas are bright red.[11]

- Acorns: Annual, sessile or stalked; nut ovoid or oblong, round at the apex, light brown, shining, three-quarters to an inch long; cup-shaped, enclose about one-fourth of the nut, tomentose on the outside, tuberculate at base, scales with short obtuse tips becoming smaller and thinner toward the rim.[5] White oak acorns (referring to Q. alba and all its close relatives) have no epigeal dormancy and germination begins readily without any treatment. In most cases, the oak root sprouts in the fall, with the leaves and stem appearing the next spring. The acorns take only one growing season to develop unlike the red oak group, which require two years for maturation.[11]

Distribution

Q. alba is fairly tolerant of a variety of habitats, and may be found on ridges, in valleys, and in between, in dry and moist habitats, and in moderately acid and alkaline soils. It is mainly a lowland tree, but reaches altitudes of 5,249 ft in the Appalachian Mountains. It is often a component of the forest canopy in an oak-heath forest.[13][14]

Uses

Cultivation

Quercus alba is cultivated as an ornamental tree somewhat infrequently due to its slow growth and ultimately huge size. It is not tolerant of urban pollution and road salt and due to its large taproot, is unsuited for a street tree or parking strips/islands.

Woodcraft

White oak has tyloses that give the wood a closed cellular structure, making it water- and rot-resistant. Because of this characteristic, white oak is used by coopers to make wine and whiskey barrels as the wood resists leaking. It has also been used in construction, shipbuilding, agricultural implements, and in the interior finishing of houses.[5]

It was a signature wood used in mission style oak furniture by Gustav Stickley in the Craftsman style of the Arts and Crafts movement.

White oak is used extensively in Japanese martial arts for some weapons, such as the bokken and jo. It is valued for its density, strength, resiliency and relatively low chance of splintering if broken by impact, relative to the substantially cheaper red oak.

USS Constitution is made of white oak and southern live oak, conferring additional resistance to cannon fire. Reconstructive wood replacement of white oak parts comes from a special grove of Quercus alba known as the "Constitution Grove" at Naval Surface Warfare Center Crane Division.[15]

Wildlife food

The acorns are much less bitter than the acorns of red oaks. They are small relative to most oaks, but are a valuable wildlife food, notably for turkeys, wood ducks, pheasants, grackles, jays, nuthatches, thrushes, woodpeckers, rabbits, squirrels, and deer. The white oak is the only known food plant of the Bucculatrix luteella and Bucculatrix ochrisuffusa caterpillars.

The young shoots of many eastern oak species are readily eaten by deer.[16] Dried oak leaves are also occasionally eaten by white-tailed deer in the fall or winter.[17] Rabbits often browse twigs and can girdle stems.[16]

Oak barrels

Barrels made of American white oak are commonly used for oak aging of wine, in which the wood is noted for imparting strong flavors.[18] Also, by federal regulation, bourbon whiskey must be aged in charred new oak (generally understood to mean specifically American white oak) barrels.[19]

In culture

White oak has served as the official state tree of Illinois after selection by a vote of school children. There are two "official" white oaks serving as state trees, one located on the grounds of the governor's mansion, and the other in a schoolyard in the town of Rochelle. The white oak is also the state tree of Connecticut and Maryland. The Wye Oak, probably the oldest living white oak until it fell because of a thunderstorm on June 6, 2002, was the honorary state tree of Maryland.

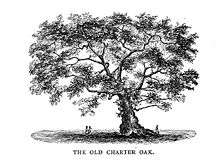

Being the subject of a legend as old as the colony itself, the Charter Oak of Hartford, Connecticut is one of the most famous white oaks in America. An image of the tree now adorns the reverse side of the Connecticut state quarter.

The white oak from the movie The Shawshank Redemption, known as the "Shawshank Tree" and the "Tree of Hope", was estimated to be more than 200 years old when it fell. The tree is seen during the last ten minutes of the movie. As the movie gained fame, the tree became popular as well, and used to attract tens of thousands of movie fans and tourists every year. A portion of the tree came down on July 29, 2011, when the tree was split by lightning during a storm. The remaining half of the tree fell during heavy winds almost exactly five years later, on July 22, 2016.

Chemistry

Grandinin/roburin E, castalagin/vescalagin, gallic acid, monogalloyl glucose (glucogallin) and valoneic acid dilactone, monogalloyl glucose, digalloyl glucose, trigalloyl glucose, ellagic acid rhamnose, quercitrin and ellagic acid are phenolic compounds found in Q. alba.[20]

See also

- Creek Council Oak Tree

- Linden Oak, possibly the largest living white oak in the United States

- Central and southern Appalachian montane oak forest

References

- ↑ "Quercus alba", NatureServe Explorer, NatureServe, retrieved 2007-07-06

- ↑ The Plant List, Quercus alba L.

- ↑ "Quercus alba". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2013.

- ↑ http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/~adk/oldlisteast/#spp

- 1 2 3 4 5 Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scriber's Sons. pp. 328–332. ISBN 0-87338-838-0.

- ↑ "An American Champion: Maryland's Wye Oak". Special Collections. National Agricultural Library. June 12, 2002. Archived from the original on June 12, 2002.

- ↑ "THSSH Profile – The Historic Basking Ridge Oak Tree". The Historical Society of Somerset Hills. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Nutt, Amy Ellis (June 27, 2016). "The oldest white oak tree in the country is dying — and no one knows why". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ Barron, James (October 16, 2016). "A 600-Year-Old Oak Tree Finally Succumbs". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ Tirmenstein, D. A. (1991). "Quercus alba". Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Nixon, Kevin C. "Quercus alba ". Flora of North America (FNA). Missouri Botanical Garden – via eFloras.org.

- ↑ Niche Timbers White Oak Archived October 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Natural Communities of Virginia Classification of Ecological Community Groups (Version 2.3), Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, 2010 Archived January 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Schafale, M. P. and A. S. Weakley. 1990. Classification of the natural communities of North Carolina: third approximation. North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation.

- ↑ "Materials on USS Constitution". San Francisco National Maritime Park Association. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- 1 2 Houston, David R. 1971. Noninfectious diseases of oaks. In: Oak symposium: Proceedings; 1971 August 16–20; Morgantown, WV. Upper Darby, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station: 118-123. [9088]

- ↑ Van Lear, David H.; Johnson, Von J. 1983. Effects of prescribed burning in the southern Appalachian and upper Piedmont forests: a review. Forestry Bull. No. 36. Clemson, SC: Clemson University, College of Forest and Recreation Resources, Department of Forestry. 8 p. [11755]

- ↑ D. Sogg "White Wines, New Barrels: The taste of new oak gains favor worldwide" Wine Spectator July 31, 2001

- ↑ "27 C.F.R. sec 5.22(l)(1)". Ecfr.gpoaccess.gov. Retrieved 2013-06-21.

- ↑ Analysis of oak tannins by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. Pirjo Mämmelä, Heikki Savolainen, Lasse Lindroos, Juhani Kangas and Terttu Vartiainen, Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 891, Issue 1, 1 September 2000, Pages 75-83, doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00624-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quercus alba. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Quercus alba |

Taxonomy

- "Quercus alba L.". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – via The Plant List.

- "Quercus alba". Flora of North America (FNA). Missouri Botanical Garden – via eFloras.org.

- "Quercus alba L.". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Genetics

- "Quercus alba". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- "Quercus alba L.". IPCN Chromosome Reports. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 3 February 2016 – via Tropicos.org.

Distribution

- Distribution Map, Quercus alba at Flora of North America, eFloras.org.

- "Quercus alba". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA.

Media

- Vanderbilt University: Quercus alba images

- Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden: Quercus alba L. images

Further reading

- Quercus alba at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Chattooga Conservancy. The Ecology of the White Oak

- Rogers, Robert (1990). "Quercus alba". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). 2 – via Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry (www.na.fs.fed.us).