Quantum gate

In quantum computing and specifically the quantum circuit model of computation, a quantum gate (or quantum logic gate) is a basic quantum circuit operating on a small number of qubits. They are the building blocks of quantum circuits, like classical logic gates are for conventional digital circuits.

Unlike many classical logic gates, quantum logic gates are reversible. However, it is possible to perform classical computing using only reversible gates. For example, the reversible Toffoli gate can implement all Boolean functions. This gate has a direct quantum equivalent, showing that quantum circuits can perform all operations performed by classical circuits.

Quantum logic gates are represented by unitary matrices. The most common quantum gates operate on spaces of one or two qubits, just like the common classical logic gates operate on one or two bits. As matrices, quantum gates can be described by 2^n × 2^n sized unitary matrices, where n is the number of qubits. The variables that the gates act upon, the quantum states, are vectors in 2n complex dimensions, where n again is the number of qubits of the variable: The base vectors are the possible outcomes if measured, and a quantum state is a linear combinations of these outcomes.

Measurement

Measurement appears as similiar to a quantum gate even though it is not a gate, because measurement actively alters the observed variable. Measurement takes a quantum state and projects it to one of the base vectors, with a likelihood equal to the square of the vectors depth along that base vector. This is a non-reversible operation as it sets the quantum state equal to the base vector that represents the measured state (the state "collapses" to a definite singular value). Why and how this is so is called the measurement problem.

If two different quantum registers are entangled (they are not lineary independent), measurement of one register affects or reveals the state of the other register by partially or entirely collapsing its state. An example of such a lineary inseparable state is the EPR pair, which can be constructed with the CNOT and the Hadamard gates, described below. This effect is used in many algorithms: If two variables A and B are maximally entangled, a function F is applied to A such that A is updated to the value of F(A), followed by measurement of A, then F(B) = A. This way, measurement can be used to find the reverse of functions. This is for example used in Shors algorithm. Measurement also have an active role in quantum teleportation.

Commonly used gates

Quantum gates are usually represented as matrices. A gate which acts on k qubits is represented by a 2k x 2k unitary matrix. The number of qubits in the input and output of the gate have to be equal. The action of the gate on a specific quantum state is found by multiplying the vector which represents the state by the matrix representing the gate. In the following, the vector representation of a single qubit is

- ,

and the vector representation of two qubits is

- ,

where is the basis vector representing a state where the first qubit is in the state and the second qubit in the state .

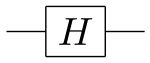

Hadamard gate

The Hadamard gate acts on a single qubit. It maps the basis state to and to , which means that a measurement will have equal probabilities to become 1 or 0 (i.e. creates a superposition). It represents a rotation of about the axis . Equivalently, it is the combination of two rotations, about the X-axis followed by about the Y-axis. It is represented by the Hadamard matrix:

- .

The hadamard gate is the one-qubit version of the quantum fourier transform.

Since where I is the identity matrix, H is indeed a unitary matrix.

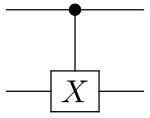

Pauli-X gate (= NOT gate)

The Pauli-X gate acts on a single qubit. It is the quantum equivalent of the NOT gate for classical computers (with respect to the standard basis , , which privileges the Z-direction) . It equates to a rotation of the Bloch sphere around the X-axis by π radians. It maps to and to . Due to this nature, it is sometimes called bit-flip. It is represented by the Pauli matrix:

- .

where I is the identity matrix

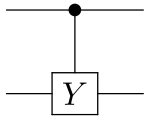

Pauli-Y gate

The Pauli-Y gate acts on a single qubit. It equates to a rotation around the Y-axis of the Bloch sphere by π radians. It maps to and to . It is represented by the Pauli Y matrix:

- .

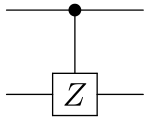

Pauli-Z gate

The Pauli-Z gate acts on a single qubit. It equates to a rotation around the Z-axis of the Bloch sphere by π radians. Thus, it is a special case of a phase shift gate (next) with θ=π. It leaves the basis state unchanged and maps to . Due to this nature, it is sometimes called phase-flip. It is represented by the Pauli Z matrix:

- .

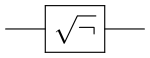

Square root of NOT gate (√NOT)

The NOT gate acts on a single qubit.

- .

, so this gate is the square root of the NOT gate.

Similar squared root-gates can be constructed for all other gates by finding the unitary matrix that, multiplied by itself, yields the gate one wishes to construct the squared root gate of. All fractional exponents of all gates can be created in this way. (Only approximations of irrational exponents are possible to synthesize from composite gates whose elements are not themselves irrational, since exact synthesis would result in infinite gate depth.)

Phase shift gates

This is a family of single-qubit gates that leave the basis state unchanged and map to . The probability of measuring a or is unchanged after applying this gate, however it modifies the phase of the quantum state. This is equivalent to tracing a horizontal circle (a line of latitude) on the Bloch sphere by radians.

where is the phase shift. Some common examples are the gate where , the phase gate where and the Pauli-Z gate where .

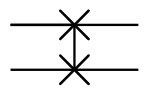

Swap gate

The swap gate swaps two qubits. With respect to the basis , , , , it is represented by the matrix:

- .

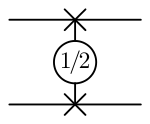

Square root of Swap gate

The sqrt(swap) gate performs half-way of a two-qubit swap. It is universal such that any quantum many qubit gate can be constructed from only sqrt(swap) and single qubit gates.

- .

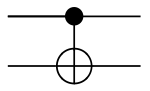

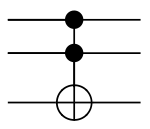

Controlled gates

Controlled gates act on 2 or more qubits, where one or more qubits act as a control for some operation. For example, the controlled NOT gate (or CNOT) acts on 2 qubits, and performs the NOT operation on the second qubit only when the first qubit is , and otherwise leaves it unchanged. It is represented by the matrix

- .

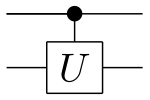

More generally if U is a gate that operates on single qubits with matrix representation

- ,

then the controlled-U gate is a gate that operates on two qubits in such a way that the first qubit serves as a control. It maps the basis states as follows.

The matrix representing the controlled U is

- .

When U is one of the Pauli matrices, σx, σy, or σz, the respective terms "controlled-X", "controlled-Y", or "controlled-Z" are sometimes used.[1]

The CNOT gate is generally used in quantum computing to generate entangled states.

Toffoli gate

The Toffoli gate, also CCNOT gate, is a 3-bit gate, which is universal for classical computation. The quantum Toffoli gate is the same gate, defined for 3 qubits. If the first two bits are in the state , it applies a Pauli-X (or NOT) on the third bit, else it does nothing. It is an example of a controlled gate. Since it is the quantum analog of a classical gate, it is completely specified by its truth table.

| Truth table | Matrix form | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It can be also described as the gate which maps to .

Fredkin gate

The Fredkin gate (also CSWAP gate) is a 3-bit gate that performs a controlled swap. It is universal for classical computation. As with the Toffoli gate it has the useful property that the numbers of 0s and 1s are conserved throughout, which in the billiard ball model means the same number of balls are output as input.

| Truth table | Matrix form | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ising gate

The Ising gate (or XX gate) is a 2-bit gate that is implemented natively in some trapped-ion quantum computers[2][3]. It is defined as

Universal quantum gates

Informally, a set of universal quantum gates is any set of gates to which any operation possible on a quantum computer can be reduced, that is, any other unitary operation can be expressed as a finite sequence of gates from the set. Technically, this is impossible since the number of possible quantum gates is uncountable, whereas the number of finite sequences from a finite set is countable. To solve this problem, we only require that any quantum operation can be approximated by a sequence of gates from this finite set. Moreover, for unitaries on a constant number of qubits, the Solovay–Kitaev theorem guarantees that this can be done efficiently.

One simple set of two-qubit universal quantum gates is the Hadamard gate (), the gate , and the controlled NOT gate.

A single-gate set of universal quantum gates can also be formulated using the three-qubit Deutsch gate , which performs the transformation[4]

The universal classical logic gate, the Toffoli gate, is reducible to the Deutsch gate, , thus showing that all classical logic operations can be performed on a universal quantum computer.

Another set of universal quantum gates consists of the Ising gate and the phase-shift gate. These are the set of gates natively available in some trapped-ion quantum computers [3].

History

The current notation for quantum gates was developed by Barenco et al.,[5] building on notation introduced by Feynman.[6]

See also

Notes

- ↑ M. Nielsen and I. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- ↑ http://online.kitp.ucsb.edu/online/mbl_c15/monroe/pdf/Monroe_MBL15Conf_KITP.pdf

- 1 2 http://iontrap.umd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/nature18648.pdf

- ↑ Deutsch, David (September 8, 1989), "Quantum computational networks", Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A, 425 (1989): 73–90, Bibcode:1989RSPSA.425...73D, doi:10.1098/rspa.1989.0099

- ↑ Phys. Rev. A 52 3457–3467 (1995), doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.3457 10.1103; e-print arXiv:quant-ph/9503016

- ↑ R. P. Feynman, "Quantum mechanical computers", Optics News, February 1985, 11, p. 11; reprinted in Foundations of Physics 16(6) 507–531.

References

- M. Nielsen and I. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press, 2000