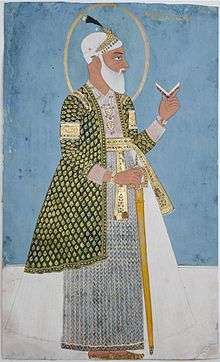

Qamar-ud-din Khan, Asif Jah I

| Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi | |

|---|---|

| Chin Qilich Khan, NIzam-u-Mulk, Asaf Jah | |

Asaf Jah I, Yamin-us-Sultanat, Rukun-us-Sultanat, Jumlat-ul-Mulk, Madaar-ul-Maham, Nizam-ul-Mulk, Khan-i-Dauran, Nawab Mir Ghazi-ud-din Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi Bahadur, Fath Jang, Sipah Salar, Nawab Subedar-i-Deccan | |

| Nizam of Hyderabad | |

| Reign | 31 July 1724 – 1 June 1748 |

| Predecessor | none |

| Successor | Nasir Jang Mir Ahmad |

| Born |

20 August 1671 Agra, Mughal India (now in Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Died |

1 June 1748 (age 76) Burhanpur, Maratha India (now in Madhya Pradesh, India) |

| Buried |

Khuldabad (near Aurangabad), Hyderabad State, Mughal India (now in Maharashtra, India) |

| Spouse(s) | Umda Begum, Saidunnisa Begum, Goutham Valluri |

|

Issue

6 sons, 7 daughters | |

| Father | Nawab Ghazi ud-Din Khan Feroze Jung I Siddiqi Bayafandi Bahadur (Farzand-i-Arjumand)Ghazi Uddin Siddiqi. |

| Mother | Wazir un-nisa Begum |

| Religion | Islam |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch | Nizam of Hyderabad |

| Rank | Sowar, Faujdar, Grand Vizier, Subadar, Nizam |

| Battles/wars |

Mughal-Maratha Wars Nader Shah's invasion of the Mughal Empire Battle of Karnal |

Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan Siddiqi Bayafandi (20 August 1671 – 1 June 1748) was a Turkic[1] nobleman with some Arab ancestry and the founder of the Asaf Jahi dynasty. He established the Hyderabad state, and ruled it from 1724 to 1748.[2] He is also known by his titles Chin Qilich Khan (awarded by emperor Aurangzeb in 1690–91[3]), Nizam-ul-Mulk (awarded by Farrukhsiyar in 1713[4]) and Asaf Jah (awarded by Muhammad Shah in 1725[5]).

According to his contemporary Shah Waliullah and the British historian Henry George Briggs, Asaf Jah I was the most influential man in the Indian Subcontinent after the death of Aurangzeb.

Early life

He was born to Ghazi ud-Din Khan Siddiqi Feroze Jung I and his first wife Wazir un-nisa Begum at Agra on 20 August 1671 as Mir Qamar ud-din Khan Siddiqi.[6] The name was given to him by the Mughal Emperor Aurangazeb.[7] His paternal and maternal grandparents were both important Mughal generals and courtiers namely; Qilich Khan II (Paternal) and Jumlat-ul-Mulk Allami Sa'adullah Khan (Maternal), the Vizier of Emperor Shah Jahan.

He was educated privately.[6] At the age of six, Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan accompanied his father to the Mughal court in 1677. Emperor Aurangzeb awarded him a Mansab.

Loyalty to Aurangzeb

Mir Qamar-ud-din Khan displayed considerable skill as a warrior and before he reached his teens began accompanying his father into battle. In 1688 aged 17 he joined his father in the successful assault on the fort of Adoni and was promoted to the rank of 2000 zat and 500 horse and presented with the finest Arab steed with gold trappings and a pastille perfumed with ambergris from the Mughal court.

At the age of nineteen, the Emperor bestowed on him the title "Chin Fateh Khan". He was also gifted a female elephant and at age 20 he was bestowed with the title of "Chin Qilich Khan" (boy swordsman) for surviving an attack that blew off three of his horse's legs during the Siege of Wagingera Fort. For fighting on and capturing the fort he was raised to rank of 5000 horse and awarded 15 million dams, a jeweled sabre and a third elephant.

At 26, he was appointed Commander in Chief and Viceroy, first in Bijapur, then Malwa and later of the Deccan.[7]

He inherited his family's military prowess. Henry George Briggs, a historian, wrote "If Moosulman were accustomed to perpetuate the memory of their heroes by posthumous ovations, India might have seen a hundred statues of her greatest Mohammedan hero of the eighteenth century".

Life after Aurangzeb

After Aurangzeb's death he was appointed Governor of Oudh. After Bahadur Shah's (Muazzam Shah i Alam Bahadur Shah the 1st) death he opted for a private life in Delhi. His sabbatical was cut short when in 1712 the sixth of Aurangzeb's successors, Farrukhsiyar son of Azeem Ush Shaan convinced him to take up the post of Viceroy of the Deccan with the title of Nizam ul-Mulk (Regulator of the Realm) Fateh Jung.

His enemies accuse Nizam ul-Mulk of building his own power-base independently of the Mughals in Delhi, while continuing to give obeisance to the throne and even remitting money to the centre. He was then called upon by Farrukhsiyar to help fight off the Sayyid Brothers. Farrukhsiyar lost his strife against the Saadaat i Baarha Sayyid Brothers and was killed.

Vizier of the Mughal Sultanate

Later Nizam ul-Mulk was rewarded for defeating the Saiyyid Brothers with the post of Vizier in the court of Muhammad Shah, the 18-year-old successor.

But all did not work as planned. Nizam ul-Mulk's attempts to reform the corrupt Mughal administration with its cliques of concubines and eunuchs created many enemies. According to his biographer, Yusuf Husain, he grew to hate the "harlots and jesters" who were the Emperor's constant companions and greeted all great nobles of the realm with lewd gestures and offensive epithets. Nizam ul-Mulk's desire to restore the etiquette of the Court and the discipline of the State to the standard of Shah Jahan's time earned him few friends. The courtiers poisoned the mind of the Emperor against him.

Viceroy of the Deccan

In 1724 Nizam ul-Mulk resigned his post in disgust and set off for the Deccan to resume the Vice-royalty, only to find Mubariz Khan, who had been appointed governor by Emperor Farrukhsiyar nine years earlier, refusing to vacate the post. Mubariz Khan had successfully restored law and order in the Deccan but he was also loyal to the Mughal throne making only token payments and dividing plum administrative posts among his sons, his uncle and his favourite slave eunuchs. Unimpressed by the up-start occupying what he considered to be his rightful place, Nizam ul-Mulk gathered his forces at Shakarkhelda in Berar for a showdown with Mubariz Khan's army. The encounter was short but decisive. Wrapped in his bloodsoaked shawl, Mubariz Khan drove his war elephant into battle until he died from his wounds. His severed head was then sent to Delhi as proof of Nizam ul-Mulk's determination to annihilate anyone who stood in his way.

Now came from the Emperor an elephant, jewels and the title of Asaf Jah, with directions to settle the country, repress the turbulent, punish the rebels and cherish the people. Asaf Jah, or the one equal to Asaf, the Grand Vizier in the court of King Solomon, was the highest title that could be awarded to a subject of the Mughal Empire. There were no lavish ceremonies to mark the establishment of the Asaf Jahi dynasty in 1724. The inauguration of the first Nizam took place behind closed doors in a private ceremony attended by the new ruler's closest advisors. Nizam ul-Mulk never formally declared his independence and insisted that his rule was entirely based on the trust reposed in him by the Mughal Emperor.

The Nizams had no throne, no crown and no symbol of sovereignty. Coins were minted with the Emperor's name until 1858. It was in the name of the Mughal ruler and not the Nizam that prayers were read out in the Friday Sermon. Qamaruddin Khan Siddiqi was essentially the servant of the Mughal Emperors.

As the Viceroy of the Deccan, the Nizam was the head of the executive and judicial departments and the source of all civil and military authority of the Mughal empire in the Deccan. All officials were appointed by him directly or in his name. Assisted by a Diwan the Nizam drafted his own laws, raised his own armies, flew his own flag and formed his own government.

Acknowledging Muhammad Shah's farman, Nizam ul-mulk had good reason to be grateful. Alongside his own personal wealth came the spoils of war and status, he was also entitled to the lion's share of gold unearthed in his dominions, the finest diamonds and gems from Golconda mines and the income from his vast personal estates.

He then divided his newly acquired kingdom into three parts. One third became his own private estate known as the Sarf-i-Khas, one third was allotted for the expenses of the government and was known as the Diwans territory, and the remainder was distributed to Muslim nobles (Jagirdar, Zamindars, Deshmukh), who in return paid nazars (gifts) to the Nizam for the privilege of collecting revenue from the villages under their suzerainty. The most important of these were the Paigah estates. The Paigah's doubled up as generals, making it easy to raise an army should the Nizams Dominions come under attack. They were the equivalent to the Barmakids for the Abbasid Caliphate. Only second to the Nizams family, they were very important in the running of the government and even today their legacy lingers on with ruined palaces and tombs dotted around the once very feudal city of Hyderabad. On the sanads (scrolls) granting them their lands, inscribed in Persian were the words "as long as the Sun and the Moon are in rotation". The owners of the estates were mostly absentee landlords who cared little for the condition of the lands under their control. Jagirs were usually split into numerous pieces in order to prevent the most powerful of the nobles from entertaining any thought of carving out an empire for themselves. The system, which continued relatively unchanged until 1950, ensured a steady source of income for the state treasury and the Nizam himself.

Usage of War elephants

During a campaign against the Maratha in the year 1730, Nizam-ul-Mulk had no less than 1026 War elephants, 225 of which were armoured.[8]

Subehdar Nawab of Assam

He was appointed Viceroy of Assam in 1720 he was Also given a title Nawab of Assam. He ruled until 1735.

War against the Marathas

Warid, written proverb describing Asaf Jah I and Samsam-ud-Daula's campaign against the Marathas in 1734[9]

In 1725, the Marathas clashed with the Nizam, who refused to pay Chauth and Sardeshmukhi to the Marathas. The war began in August 1727 and ended in March 1728. The Nizam was given a crushing defeat at Battle of Palkhed near Nashik by Bajirao I, the son of Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath Bhatt.[10]

Nader Shah

In 1738, From beyond the Hindu kush, Nader Shah started advancing towards Delhi through Afghanistan and the Punjab.

Nizam ul-Mulk sent his troops to Karnal, where Mughal Emperor Muhammed Shah's forces had gathered to turn back the Persian army. But the combined forces were cannon fodder for the Persian cavalry and its superior weaponry and tactics. Nader Shah defeated the combined armies of Muhammed Shah and the Nizam.

Nader Shah entered Delhi and stationed his troops there. Some locals of Delhi had a quarrel and attacked his soldiers. At this, Nader Shah flew into a rage, drew out his sword from the scabbard and ordered the City to be looted and ransacked. Muhammad Shah was unable to prevent Delhi from being destroyed.

When Nader Shah ordered the massacre in Delhi, neither the helpless Mughal Emperor Muhammed Shah nor any of his Ministers had the courage to speak to Nader Shah and negotiate for truce.

Only Asif Jah came forward and risked his life for by going to Nader Shah and asking him to end the bloodbath of the city. Legend has it that Asif Jah said to Nader Shah "You have taken the lifes of thousands of people of the city, if you still wish to continue the bloodshed, then bring those dead back to life and then kill them again, for there are none left to be killed". These words had a tremendous impact on Nader Shah - he immediately put his sword inside its scabbard, ended the massacre and returned to Persia.

Later life

The Nizam was well suited to rule his own territory.The administration was under control.

In March 1742, the British who were based in Fort St George in Madras sent a modest hamper to Nizam ul-mulk in recognition of his leadership of the most important of the Mughal successor states. Its contents included a gold throne, gold and silver threaded silk from Europe, two pairs of large painted looking glasses, and equipage for coffee cups, 163.75 yards of green and 73.5 yards of crimson velvet, brocades, Persian carpets, a gold ceremonial cloth, two Arab horses, half a dozen ornate rose-water bottles and 39.75 chests of rose water – enough to keep the Nizam and his entire darbar fragrant for the rest of his reign. In return, the Nizam sent one horse, a piece of jewelery and a note warning the British that they had no right to mint their own currency, to which they complied.

It was after Nizam ul-mulk's death that his son and grandson sought help from the British and French in order to win the throne. Just days before he died in 1748, Asaf Jah dictated his last will and testament. The 17 clause document was a blueprint for governance and personal conduct that ranged from advice on how to keep the troops happy and well fed to an apology for neglecting his wife. He then reminded his successors to remain subservient to the Mughal Emperor who had granted them their office and rank. He warned against declaring war unnecessarily, but if forced to do so to seek the help of elders and saints and follow the sayings and practices of the Prophet. Finally, he insisted to his sons that "you must not lend your ears to tittle-tattle of the backbiters and slanderers, nor suffer the riff-raff to approach your presence."

Legacy

Nizam-ul-Mulk is remembered as laying the foundation for what would become one of the most important Muslim states outside the Middle East by the first half of the twentieth century. Hyderabad state survived right through the period of British rule up to the time of Indian independence 1947, and was indeed the largest – the state covered an extensive 95,337 sq. miles, an area larger than Mysore or Gwalior and the size of Nepal and Kashmir put together [11] (although it was the size of France when the first Nizam held reign) – and one of the most prosperous, among the princely states of the British Raj. The titles of "Nizam Ul Mulk" and "Asaf Jah" that were bestowed on him by the Mughal Emperors, carried his legacy as his descendants ruled under the title of " Nizam of Hyderabad" and the dynasty itself came to be known as the Asaf Jahi Dynasty.

Death

Nizam ul-mulk died aged 76. He died at Burhanpur, 1 June 1748 and was buried at mazaar of Shaikh Burhan ud-din Gharib Chisti, Khuldabad, near Aurangabad, where Aurangazeb is also buried.

Titles[6]

- 1685 : Khan

- 1691 : Khan Bahadur

- 1697 : Chin Qilich Khan (by Emperor Aurangazeb[7])

- 9 December 1707 : Khan-i-Dauran Bahadur

- 1712 : Ghazi ud-din Khan Bahadur and Firuz Jang

- 12 January 1713 : Khan-i-Khanan, Nizam ul-Mulk and Fateh Jang (by Emperor Farukh Siar[7])

- 12 July 1737 : Asaf Jah (by Emperor Muhammad Shah[7])

- 26 February 1739 : Amir ul-Umara and Bakshi ul-Mamalik (Paymaster-General)

Positions[6]

- 1701–1705 : Faujdar of the Carnatic and Talikota

- 1705–1706 : Faujdar of the Bijapur, Azamnagar and Belgaum

- 1706–1707 : Faujdar of Raichur, Talikota, Sakkhar and Badkal

- 1707 : Faujdar of Firoznagar and Balkona

- 9 December 1707 – 6 February 1711 : Subedar of Oudh and Faujdar of Gorakhpur

- 12 January 1713 – April 1715 : Subedar of the Deccan and Faujdar of the Carnatic

- April 1717-7 January 1719 : Faujdar of Moradabad

- 7 February-15 March 1719: Subedar of Patna

- 15 March 1719 – 1724 : Subedar of Malwa

- 1722–1724 : Subedar of Gujarat

Military promotions

- Commander of 400 foot and 100 horse, 1684 (roughly equivalent to a modern battalion commander or lieutenant-colonel)

- 400 foot and 500 horse, 1691

- 400 foot and 900 horse, 1698

- 3,000 foot and 500 horse, 1698 (roughly equivalent to a modern regimental commander or colonel)

- 3,500 foot and 3,000 horse, 1698 (roughly equivalent to a modern brigade commander or brigadier)

- 4,000 foot and 3,000 horse, 1699,

- 4,000 foot and 3,600 horse, 1700

- 4,000 foot and 4,000 horse, 1702 (roughly equivalent to a modern division commander or major-general)

- 5,000 foot and 5,000 horse, 1705

- 6,000 foot and 6,000 horse, 9 December 1707

- 7,000 foot and 7,000 horse, 27 January 1708

- 8,000 foot and 8,000 horse, 12 January 1713

- 9,000 foot and 9,000 horse, 8 February 1722

| Qamar-ud-din Khan, Asif Jah I | ||

| Preceded by None |

Nizam of Hyderabad 1720 – 1 June 1748 |

Succeeded by Nasir Jang Mir Ahmad |

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asaf Jah I. |

- ↑ Usha R Bala Krishnan (2001). Jewels Of The Nizams. p. 14.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ↑ William Irvine (1922). Later Mughals . Vol. 2, 1719–1739. p. 271. OCLC 452940071.

- ↑ Jaswant Lal Mehta (2005). Advanced study in the history of modern India 1707–1813. Sterling. p. 143. ISBN 9781932705546.

- ↑ Rai, Raghunath. History. FK Publications. ISBN 9788187139690.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Asaf Jahi Dynasty : Genealogy".

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hyderabad on the Net : The Nizams".

- ↑ Oxford Progressive English by Rachel Redford

- ↑ Full text of "Later Mughals;"

- ↑ Bernard Law Montgomery Montgomery of Alamein (Viscount) (2000). A Concise History of Warfare. Wordsworth Editions Limited. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-84022-223-4.

- ↑ "Hyderabad Online : The Nizam Dynasty".

- ↑ hyder3

- Zubrzycki, John (2007). The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback. Pan Australia. ISBN 978-0-330-42321-2.

Further reading

- Faruqi, Munis D. (2013), "At Empire's End: The Nizam, Hyderabad and Eighteenth-century India", in Richard M. Eaton; Munis D. Faruqui; David Gilmartin; Sunil Kumar, Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History: Essays in Honour of John F. Richards, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–38, ISBN 978-1-107-03428-0