Q fever

| Q fever | |

|---|---|

| |

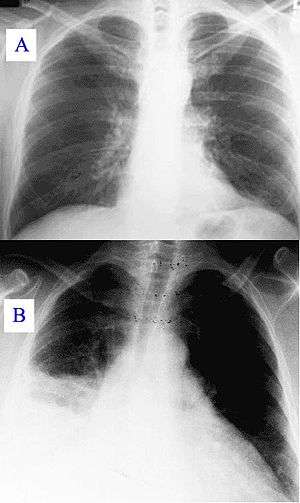

| Immunohistochemical detection of C. burnetii in resected cardiac valve of a 60-year-old man with Q fever endocarditis, Cayenne, French Guiana: Monoclonal antibodies against C. burnetii and hematoxylin were used for staining; original magnification is ×50. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | A78 |

| ICD-9-CM | 083.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 11093 |

| MedlinePlus | 001337 |

| eMedicine | med/1982 ped/1973 |

| Patient UK | Q fever |

| MeSH | D011778 |

Q fever is a disease caused by infection with Coxiella burnetii,[1] a bacterium that affects humans and other animals. This organism is uncommon, but may be found in cattle, sheep, goats, and other domestic mammals, including cats and dogs. The infection results from inhalation of a spore-like small-cell variant, and from contact with the milk, urine, feces, vaginal mucus, or semen of infected animals. Rarely, the disease is tick-borne.[2] The incubation period is 9–40 days. Humans are vulnerable to Q fever, and infection can result from even a few organisms.[3] The bacterium is an obligate intracellular pathogenic parasite.

Signs and symptoms

Incubation period is usually two to three weeks.[4] The most common manifestation is flu-like symptoms with abrupt onset of fever, malaise, profuse perspiration, severe headache, muscle pain, joint pain, loss of appetite, upper respiratory problems, dry cough, pleuritic pain, chills, confusion, and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. About half of infected individuals exhibit no symptoms.[4]

During its course, the disease can progress to an atypical pneumonia, which can result in a life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome, whereby such symptoms usually occur during the first four to five days of infection.

Less often, Q fever causes (granulomatous) hepatitis, which may be asymptomatic or becomes symptomatic with malaise, fever, liver enlargement, and pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Whereas transaminase values are often elevated, jaundice is uncommon. Retinal vasculitis is a rare manifestation of Q fever.[5]

The chronic form of Q fever is virtually identical to inflammation of the inner lining of the heart (endocarditis),[6] which can occur months or decades following the infection. It is usually fatal if untreated. However, with appropriate treatment, the mortality falls to around 10%.

Clinical signs in animals

Cattle, goats, and sheep are most commonly infected, and can serve as a reservoir for the bacteria. Q fever is a well-recognized cause of abortions in ruminants and pets. C. burnetii infection in dairy cattle has been well documented and its association with reproductive problems in these animals has been reported in Canada, the US, Cyprus, France, Hungary, Japan, Switzerland, and Germany.[7] For instance, in a study published in 2008,[8] a significant association has been shown between the seropositivity of herds and the appearance of typical clinical signs of Q fever, such as abortion, stillbirth, weak calves, and repeat breeding. Moreover, experimental inoculation of C. burnetii in cattle induced not only respiratory disorders and cardiac failures (myocarditis), but also frequent abortions and irregular repeat breedings.[9]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on serology[10][11] (looking for an antibody response) rather than looking for the organism itself. Serology allows the detection of chronic infection by the appearance of high levels of the antibody against the virulent form of the bacterium. Molecular detection of bacterial DNA is increasingly used. Culture is technically difficult and not routinely available in most microbiology laboratories.

Q fever can cause endocarditis (infection of the heart valves) which may require transoesophageal echocardiography to diagnose. Q fever hepatitis manifests as an elevation of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase, but a definitive diagnosis is only possible on liver biopsy, which shows the characteristic fibrin ring granulomas.[12]

Treatment

Treatment of acute Q fever with antibiotics is very effective and should be given in consultation with an infectious diseases specialist. Commonly used antibiotics include doxycycline, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and hydroxychloroquine. Chronic Q fever is more difficult to treat and can require up to four years of treatment with doxycycline and quinolones or doxycycline with hydroxychloroquine.

Q fever in pregnancy is especially difficult to treat because doxycycline and ciprofloxacin are contraindicated in pregnancy. The preferred treatment is five weeks of co-trimoxazole.[13]

Prevention

Protection is offered by Q-Vax, a whole-cell, inactivated vaccine developed by an Australian vaccine manufacturing company, CSL Limited.[14] The intradermal vaccination is composed of killed C. burnetii organisms. Skin and blood tests should be done before vaccination to identify pre-existing immunity, because vaccinating people who already have an immunity can result in a severe local reaction. After a single dose of vaccine, protective immunity lasts for many years. Revaccination is not generally required. Annual screening is typically recommended.[15]

In 2001, Australia introduced a national Q fever vaccination program for people working in “at risk” occupations. Vaccinated or previously exposed people may have their status recorded on the Australian Q Fever Register,[16] which may be a condition of employment in the meat processing industry. An earlier killed vaccine had been developed in the Soviet Union, but its side effects prevented its licensing abroad.

Preliminary results suggest vaccination of animals may be a method of control. Published trials proved that use of a registered phase vaccine (Coxevac) on infected farms is a tool of major interest to manage or prevent early or late abortion, repeat breeding, anoestrus, silent oestrus, metritis, and decreases in milk yield when C. burnetii is the major cause of these problems.[17][18]

Epidemiology

The pathogenic agent is found everywhere except New Zealand.[19] The bacterium is extremely sustainable and virulent: a single organism is able to cause an infection. The common source of infection is inhalation of contaminated dust, contact with contaminated milk, meat, or wool, and particularly birthing products. Ticks can transfer the pathogenic agent to other animals. Transfer between humans seems extremely rare and has so far been described in very few cases.

Some studies have shown more men to be affected than women,[20][21] which may be attributed to different employment rates in typical professions.

“At risk” occupations include:

- Veterinary personnel

- Stockyard workers

- Farmers

- Sheep shearers

- Animal transporters

- Laboratory workers handling potentially infected veterinary samples or visiting abattoirs

- People who cull and process kangaroos

- Hide (tannery) workers

Biological warfare

C burnetii has been developed as a biological weapon.[22] The United States investigated it as a potential biological warfare agent in the 1950s, with eventual standardization as agent OU. At Fort Detrick and Dugway Proving Ground, human trials were conducted on Whitecoat volunteers to determine the median infective dose (18 MICLD50/person i.h.) and course of infection. The Deseret Test Center dispensed biological Agent OU with ships and aircraft, during Project 112 and Project SHAD.[23] As a standardized biological, it was manufactured in large quantities at Pine Bluff Arsenal, with 5,098 gallons in the arsenal in bulk at the time of demilitarization in 1970. C. burnetii is currently ranked as a "category B" bioterrorism agent by the CDC.[24] It can be contagious, and is very stable in aerosols in a wide range of temperatures. Q fever microorganisms may survive on surfaces up to 60 days. It is considered a good agent in part because its ID50 (number of bacilli needed to infect 50% of individuals) is considered to be one, making it the lowest known.

History

Q fever was first described in 1935 by Edward Holbrook Derrick[25] in slaughterhouse workers in Brisbane, Queensland. The "Q"” stands for "query" and was applied at a time when the causative agent was unknown; it was chosen over suggestions of abattoir fever and Queensland rickettsial fever, to avoid directing negative connotations at either the cattle industry or the state of Queensland.[26]

The pathogen of Q fever was discovered in 1937, when Frank Macfarlane Burnet and Mavis Freeman isolated the bacterium from one of Derrick’s patients.[27] It was originally identified as a species of Rickettsia. H.R. Cox and Gordon Davis elucidated the transmission when they isolated it from ticks found in the US state of Montana in 1938.[28] It is a zoonotic disease whose most common animal reservoirs are cattle, sheep, and goats. Coxiella burnetii – named for Cox and Burnet – is no longer regarded as closely related to the Rickettsiae, but as similar to Legionella and Francisella, and is a proteobacterium.

In popular culture

An early mention of Q fever was important in one of the early Dr. Kildare films (1939, Calling Dr. Kildare). Kildare’s mentor Dr. Gillespie (Lionel Barrymore) tires of his protégé working fruitlessly on "exotic diagnoses" (“I think it’s Q fever!”) and sends him to work in a neighborhood clinic, instead.[29][30]

Q fever was also highlighted in an episode of the U.S. television medical drama House ("The Dig", season seven, episode 18).

References

- ↑ Beare PA, Samuel JE, Howe D, Virtaneva K, Porcella SF, Heinzen RA (April 2006). "Genetic diversity of the Q Fever agent, Coxiella burnetii, assessed by microarray-based whole-genome comparisons". J. Bacteriol. 188 (7): 2309–2324. PMC 1428397

. PMID 16547017. doi:10.1128/JB.188.7.2309-2324.2006.

. PMID 16547017. doi:10.1128/JB.188.7.2309-2324.2006. - ↑ "Q fever".

- ↑ Q Fever caused by Coxiella burnetii

- 1 2 Anderson, Alicia; McQuiston, Jennifer (2011). "Q Fever". In Brunette, Gary W. et al. CDC Health Information for International Travel: The Yellow Book. Oxford University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-19-976901-8.

- ↑ Kuhne F, Morlat P, Riss I, et al. (1992). "Is A29, B12 vasculitis caused by the Q fever agent? (Coxiella burnetii)". J Fr Ophtalmol (in French). 15 (5): 315–21. PMID 1430809.

- ↑ Karakousis PC, Trucksis M, Dumler JS (June 2006). "Chronic Q Fever in the United States". J. Clin. Microbiol. 44 (6): 2283–7. PMC 1489455

. PMID 16757641. doi:10.1128/JCM.02365-05.

. PMID 16757641. doi:10.1128/JCM.02365-05. - ↑ To, H; Sakai, R; Shirota, K; Kano, C; Abe, S; Sugimoto, T; Takehara, K; Morita, C; Takashima, I; Maruyama, T; Yamaguchi, T; Fukushi, H; Hirai, K (1998). "Coxiellosis in domestic and wild birds from Japan". Journal of wildlife diseases. 34 (2): 310–6. PMID 9577778. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-34.2.310.

- ↑ Czaplicki, G; Houtain, JY; Mullender, C; Porter, SR; Humblet, MF; Manteca, C; Saegerman, C (2012). "Apparent prevalence of antibodies to Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) in bulk tank milk from dairy herds in southern Belgium". Veterinary journal (London, England : 1997). 192 (3): 529–31. PMID 21962829. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.08.033.

- ↑ Plommet, M; Capponi, M; Gestin, J; Renoux, G (1973). "Fièvre Q expérimentale des bovins". Annales de recherches vétérinaires (in French). 4 (2): 325–346.

- ↑ Maurin M, Raoult D (October 1999). "Q fever". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12 (4): 518–53. PMC 88923

. PMID 10515901.

. PMID 10515901. - ↑ Scola BL (October 2002). "Current laboratory diagnosis of Q Fever". Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 13 (4): 257–262. PMID 12491231. doi:10.1053/spid.2002.127199.

- ↑ van de Veerdonk FL, Schneeberger PM (2006). "Patient with fever and diarrea". Clin Infect Dis. 42 (7): 1051–2. doi:10.1086/501027.

- ↑ Carcopino X, Raoult D, Bretelle F, Boubli L, Stein A (2007). "Managing Q fever during pregnancy: The benefits of long-term Cotrimoxazole therapy". Clin Infect Dis. 45 (5): 548–555. PMID 17682987. doi:10.1086/520661.

- ↑ "Q fever Vaccine" (PDF). CSL. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ http://cdp.ucsf.edu/fileUpload/UCSF_CDP_Q_Fever_Surveillance_Policy_Q_Neg_Wethers.pdf

- ↑ "Australian Q Fever Register". AusVet. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Camuset, P; Remmy, D (2008). "Q Fever (Coxiella burnetii) Eradication in a Dairy Herd by Using Vaccination with a Phase 1 Vaccine". Budapest: XXV World Buiatrics Congress.

- ↑ Hogerwerf, L; Van Den Brom, R; Roest, HI; Bouma, A; Vellema, P; Pieterse, M; Dercksen, D; Nielen, M (2011). "Reduction of Coxiella burnetii prevalence by vaccination of goats and sheep, the Netherlands". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (3): 379–386. PMC 3166012

. PMID 21392427. doi:10.3201/eid1703.101157.

. PMID 21392427. doi:10.3201/eid1703.101157. - ↑ Cutler SJ, Bouzid M, Cutler RR (April 2007). "Q fever". J. Infect. 54 (4): 313–8. PMID 17147957. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2006.10.048.

- ↑ Domingo P, Muñoz C, Franquet T, Gurguí M, Sancho F, Vazquez G (October 1999). "Acute Q fever in adult patients: report on 63 sporadic cases in an urban area". Clin. Infect. Dis. 29 (4): 874–9. PMID 10589906. doi:10.1086/520452.

- ↑ Dupuis G, Petite J, Péter O, Vouilloz M (June 1987). "An important outbreak of human Q fever in a Swiss Alpine valley". Int J Epidemiol. 16 (2): 282–7. PMID 3301708. doi:10.1093/ije/16.2.282.

- ↑ Madariaga MG, Rezai K, Trenholme GM, Weinstein RA (November 2003). "Q Fever: A biological weapon in your backyard". Lancet Infect Dis. 3 (11): 709–21. PMID 14592601. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00804-1.

- ↑ Deseret Test Center, Project SHAD, Shady Grove revised fact sheet

- ↑ Seshadri R, Paulsen IT, Eisen JA, et al. (April 2003). "Complete genome sequence of the Q-fever pathogen Coxiella burnetii". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (9): 5455–60. PMC 154366

. PMID 12704232. doi:10.1073/pnas.0931379100.

. PMID 12704232. doi:10.1073/pnas.0931379100. - ↑ Derrick EH (1937). ""Q" Fever a new fever entity: clinical features. diagnosis, and laboratory investigation". Med J Aust. 11: 281–299.

- ↑ Joseph E. McDade (1990). "Historical aspects of Q Fever". In Thomas J. Marrie. Q Fever, Volume I: The Disease. CRC Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-8493-5984-8.

- ↑ Burnet FM, Freeman M (1937). "Experimental studies on the virus of "Q" fever". Med J Aust. 2: 299–305.

- ↑ Davis, Gordon E.; Cox, Herald R.; Parker and R. E. Dyer, R. R.; Dyer, R. E. (1938). "A Filter-Passing Infectious Agent Isolated from Ticks". Public Health Reports. Association of Schools of Public Health. 53 (52): 2259–82. ISSN 0094-6214. JSTOR 4582746. doi:10.2307/4582746 – via JSTOR. (Registration required (help)).

- ↑ "Calling Dr. Kildare". Movie Mirrors Index. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ Kalisch, PA; Kalisch, BJ (1985). "When Americans called for Dr. Kildare: images of physicians and nurses in the Dr. Kildare and Dr. Gillespie movies, 1937–1947" (PDF). Medical Heritage. 1 (5): 348–363. PMID 11616027. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

External links

- Q fever at the CDC

- Coxiella burnetii genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID