Pxr sRNA

| Pxr sRNA | |

|---|---|

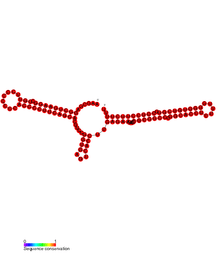

Secondary structure of Pxr sRNA. | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | Pxr |

| Rfam | RF01812 |

| Other data | |

| RNA type | sRNA |

| Domain(s) | Myxococcus xanthus, Stigmatella aurantiaca |

| SO | {{{SO}}} |

Pxr sRNA is a regulatory RNA which downregulates genes responsible for the formation of fruiting bodies in Myxococcus xanthus.[1] Fruiting bodies are aggregations of myxobacteria formed when nutrients are scarce,[2] the fruiting bodies permit a small number of the aggregated colony to transform into stress-resistant spores.[3]

Pxr exists in two forms: Pxr-L (a long form) and Pxr-S which is shorter. The short form was found to be expressed in cells during growth but is rapidly repressed during starvation. This finding implies that Pxr-S is specifically responsible for inhibiting the fruiting body development during cell growth when nutrients are abundant.[1]

Pxr homologs have only been found in one other taxon, namely Stigmatella aurantiaca. Homologs were not found in any other myxobacteria (such as Sorangium cellulosum[4] or Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans[5]) which suggests the Pxr RNA gene may have a recent evolutionary origin in the sub-clade Myxococcales.[1]

M. Xanthus obligate cheat and phoenix phenotypes

Several mutations in the Pxr sRNA gene have been observed.[6] The first mutation causes an obligate cheat (OC) phenotype to emerge, these bacteria exploit the fruiting bodies of wild-type M. Xanthus to sporulate more efficiently. This phenotype is thought to be caused by a mutation which prevents the repression of Pxr-S, thereby inhibiting the formation of fruiting bodies indefinitely. If Pxr-S is derived from Pxr-L, it may be that RNAi-like processing elements have been knocked out.[1]

In a laboratory experiment, the OC phenotype out-competed and excluded the wild type, eventually bringing about a population crash when there were not enough wild type bacteria to exploit.[6] After this event, a new phenotype emerged via spontaneous mutation dubbed phoenix (PX).[1] The PX phenotype was developmentally superior to both OC and wt, it was able to sporulate autonomously - without forming fruiting bodies and with high efficiency.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yu YT, Yuan X, Velicer GJ (May 2010). "Adaptive evolution of an sRNA that controls Myxococcus development". Science. 328 (5981): 993. PMC 3027070

. PMID 20489016. doi:10.1126/science.1187200. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

. PMID 20489016. doi:10.1126/science.1187200. Retrieved 2010-07-22. - ↑ Kuner JM, Kaiser D (July 1982). "Fruiting body morphogenesis in submerged cultures of Myxococcus xanthus". J. Bacteriol. 151 (1): 458–61. PMC 220259

. PMID 6806248. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

. PMID 6806248. Retrieved 2010-07-22. - ↑ Wireman JW, Dworkin M (February 1977). "Developmentally induced autolysis during fruiting body formation by Myxococcus xanthus". J. Bacteriol. 129 (2): 798–802. PMC 235013

. PMID 402359. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

. PMID 402359. Retrieved 2010-07-22. - ↑ Schneiker S, Perlova O, Kaiser O, et al. (November 2007). "Complete genome sequence of the myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum". Nat. Biotechnol. 25 (11): 1281–9. PMID 17965706. doi:10.1038/nbt1354.

- ↑ Thomas SH, Wagner RD, Arakaki AK, et al. (2008). "The mosaic genome of Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans strain 2CP-C suggests an aerobic common ancestor to the delta-proteobacteria". PLoS ONE. 3 (5): e2103. PMC 2330069

. PMID 18461135. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002103. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

. PMID 18461135. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002103. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- 1 2 3 Fiegna F, Yu YT, Kadam SV, Velicer GJ (May 2006). "Evolution of an obligate social cheater to a superior cooperator". Nature. 441 (7091): 310–4. PMID 16710413. doi:10.1038/nature04677.

Further reading

- Stefani G, Slack FJ (March 2008). "Small non-coding RNAs in animal development". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9 (3): 219–30. PMID 18270516. doi:10.1038/nrm2347.

- Gottesman S (July 2005). "Micros for microbes: non-coding regulatory RNAs in bacteria". Trends Genet. 21 (7): 399–404. PMID 15913835. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.05.008. Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- Chen, IC; Griesenauer, B; Yu, YT; Velicer, GJ (Jan 10, 2014). "A recent evolutionary origin of a bacterial small RNA that controls multicellular fruiting body development.". Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 73: 1–9. PMID 24418530. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.01.001.