Feng shui

| Feng shui | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

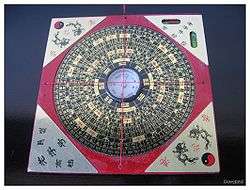

A Luopan, feng shui compass. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 風水 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 风水 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | fēngshuǐ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | wind-water | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | phong thủy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | ฮวงจุ้ย (Huang Jui) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 풍수 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 風水 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 風水 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ふうすい | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Filipino name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tagalog | Pungsóy, Punsóy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Feng shui or fengshui (pinyin: fēngshuǐ, pronounced [fə́ŋ.ʂwèi]) is a Chinese philosophical system of harmonizing everyone with the surrounding environment. It is closely linked to Taoism. The term feng shui literally translates as "wind-water" in English. This is a cultural shorthand taken from the passage of the now-lost Classic of Burial recorded in Guo Pu's commentary:[1] Feng shui is one of the Five Arts of Chinese Metaphysics, classified as physiognomy (observation of appearances through formulas and calculations). The feng shui practice discusses architecture in metaphoric terms of "invisible forces" that bind the universe, earth, and humanity together, known as qi.

There is no replicable scientific evidence that feng shui's mystical claims are real, and it is considered by the scientific community to be pseudoscience.

Historically, feng shui was widely used to orient buildings—often spiritually significant structures such as tombs, but also dwellings and other structures—in an auspicious manner. Depending on the particular style of feng shui being used, an auspicious site could be determined by reference to local features such as bodies of water, stars, or a compass.

Qi rides the wind and scatters, but is retained when encountering water.[1]

Feng shui was suppressed in mainland China during the state-imposed Cultural Revolution of the 1960s but has since then regained popularity.

The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience briefly summarizes the history and practice of feng shui. It states that the principles of feng shui related to living harmoniously with nature are "quite rational," but does not otherwise lend credibility to the nonscientific claims.[2][3] After a comprehensive 2016 evaluation of the subject by scientific skeptic author Brian Dunning, he concluded that there is nothing demonstrably real at all about the practice and stated that:

There's no real science behind feng shui... It's also a simple matter to dismiss the mystical energies said to be at its core; they simply don't exist.[4]

History

Origins

As of 2013 the Yangshao and Hongshan cultures provide the earliest known evidence for the use of feng shui. Until the invention of the magnetic compass, feng shui apparently relied on astronomy to find correlations between humans and the universe.[5] In 4000 BC, the doors of Banpo dwellings aligned with the asterism Yingshi just after the winter solstice—this sited the homes for solar gain.[6] During the Zhou era, Yingshi was known as Ding and used to indicate the appropriate time to build a capital city, according to the Shijing. The late Yangshao site at Dadiwan (c. 3500–3000 BC) includes a palace-like building (F901) at the center. The building faces south and borders a large plaza. It stands on a north-south axis with another building that apparently housed communal activities. Regional communities may have used the complex.[7]

A grave at Puyang (around 4000 BC) that contains mosaics— actually a Chinese star map of the Dragon and Tiger asterisms and Beidou (the Big Dipper, Ladle or Bushel)— is oriented along a north-south axis.[8] The presence of both round and square shapes in the Puyang tomb, at Hongshan ceremonial centers and at the late Longshan settlement at Lutaigang,[9] suggests that gaitian cosmography (heaven-round, earth-square) existed in Chinese society long before it appeared in the Zhoubi Suanjing.[10]

Cosmography that bears a striking resemblance to modern feng shui devices and formulas appears on a piece of jade unearthed at Hanshan and dated around 3000 BC. Archaeologist Li Xueqin links the design to the liuren astrolabe, zhinan zhen, and luopan.[11]

Beginning with palatial structures at Erlitou,[12] all capital cities of China followed rules of feng shui for their design and layout. During the Zhou era, the Kaogong ji (simplified Chinese: 考工记; traditional Chinese: 考工記; "Manual of Crafts") codified these rules. The carpenter's manual Lu ban jing (simplified Chinese: 鲁班经; traditional Chinese: 魯班經; "Lu ban's manuscript") codified rules for builders. Graves and tombs also followed rules of feng shui, from Puyang to Mawangdui and beyond. From the earliest records, the structures of the graves and dwellings seem to have followed the same rules.

Early instruments and techniques

The history of feng shui covers 3,500+ years[13] before the invention of the magnetic compass. It originated in Chinese astronomy.[14] Some current techniques can be traced to Neolithic China,[15] while others were added later (most notably the Han dynasty, the Tang, the Song, and the Ming).[16]

The astronomical history of feng shui is evident in the development of instruments and techniques. According to the Zhouli, the original feng shui instrument may have been a gnomon. Chinese used circumpolar stars to determine the north-south axis of settlements. This technique explains why Shang palaces at Xiaotun lie 10° east of due north. In some of the cases, as Paul Wheatley observed,[17] they bisected the angle between the directions of the rising and setting sun to find north. This technique provided the more precise alignments of the Shang walls at Yanshi and Zhengzhou. Rituals for using a feng shui instrument required a diviner to examine current sky phenomena to set the device and adjust their position in relation to the device.[18]

The oldest examples of instruments used for feng shui are liuren astrolabes, also known as shi. These consist of a lacquered, two-sided board with astronomical sightlines. The earliest examples of liuren astrolabes have been unearthed from tombs that date between 278 BC and 209 BC. Along with divination for Da Liu Ren[19] the boards were commonly used to chart the motion of Taiyi through the nine palaces.[20] The markings on a liuren/shi and the first magnetic compasses are virtually identical.[21]

The magnetic compass was invented for feng shui[22] and has been in use since its invention. Traditional feng shui instrumentation consists of the Luopan or the earlier south-pointing spoon (指南針 zhinan zhen)—though a conventional compass could suffice if one understood the differences. A feng shui ruler (a later invention) may also be employed.

Foundation theories

The goal of feng shui as practiced today is to situate the human-built environment on spots with good qi. The "perfect spot" is a location and an axis in time.[23][24]

Qi (ch'i)

Qi(氣)(pronounced "chee" in English) is a movable positive or negative life force which plays an essential role in feng shui.[26] In feng shui as in Chinese martial arts, it refers to 'energy', in the sense of 'life force' or élan vital. A traditional explanation of qi as it relates to feng shui would include the orientation of a structure, its age, and its interaction with the surrounding environment, including the local microclimates, the slope of the land, vegetation, and soil quality.

The Book of Burial says that burial takes advantage of "vital qi". Wu Yuanyin[27] (Qing dynasty) said that vital qi was "congealed qi", which is the state of qi that engenders life. The goal of feng shui is to take advantage of vital qi by appropriate siting of graves and structures.[24] Some people destroyed graveyards of their enemies to weaken their qi.[28][29][30][31][32]

One use for a loupan is to detect the flow of qi.[33] Magnetic compasses reflect local geomagnetism which includes geomagnetically induced currents caused by space weather.[34] Professor Max Knoll suggested in a 1951 lecture that qi is a form of solar radiation.[35] As space weather changes over time,[36] and the quality of qi rises and falls over time,[24] feng shui with a compass might be considered a form of divination that assesses the quality of the local environment—including the effects of space weather. Often people with good karma live in land with good qi.[37][38][39][40]

Polarity

Polarity is expressed in feng shui as yin and yang theory. Polarity expressed through yin and yang is similar to a magnetic dipole. That is, it is of two parts: one creating an exertion and one receiving the exertion. Yang acting and yin receiving could be considered an early understanding of chirality. The development of this theory and its corollary, five phase theory (five element theory), have also been linked with astronomical observations of sunspots.[41]

The Five Elements or Forces (wu xing) – which, according to the Chinese, are metal, earth, fire, water, and wood – are first mentioned in Chinese literature in a chapter of the classic Book of History. They play a very important part in Chinese thought: ‘elements’ meaning generally not so much the actual substances as the forces essential to human life.[42] Earth is a buffer, or an equilibrium achieved when the polarities cancel each other. While the goal of Chinese medicine is to balance yin and yang in the body, the goal of feng shui has been described as aligning a city, site, building, or object with yin-yang force fields.[43]

Bagua (eight trigrams)

Two diagrams known as bagua (or pa kua) loom large in feng shui, and both predate their mentions in the Yijing (or I Ching). The Lo (River) Chart (Luoshu) was developed first,[44] and is sometimes associated with Later Heaven arrangement of the bagua. This and the Yellow River Chart (Hetu, sometimes associated with the Earlier Heaven bagua) are linked to astronomical events of the sixth millennium BC, and with the Turtle Calendar from the time of Yao.[45] The Turtle Calendar of Yao (found in the Yaodian section of the Shangshu or Book of Documents) dates to 2300 BC, plus or minus 250 years.[46]

In Yaodian, the cardinal directions are determined by the marker-stars of the mega-constellations known as the Four Celestial Animals:[46]

- East

- The Azure Dragon (Spring equinox)—Niao (Bird 鳥), α Scorpionis

- South

- The Vermilion Bird (Summer solstice)—Huo (Fire 火), α Hydrae

- West

- The White Tiger (Autumn equinox)—Mǎo (Hair 毛), η Tauri (the Pleiades)

- North

- The Black Tortoise (Winter solstice)—Xū (Emptiness, Void 虛), α Aquarii, β Aquarii

The diagrams are also linked with the sifang (four directions) method of divination used during the Shang dynasty.[47] The sifang is much older, however. It was used at Niuheliang, and figured large in Hongshan culture's astronomy. And it is this area of China that is linked to Yellow Emperor (Huangdi) who allegedly invented the south-pointing spoon (see compass).[48]

Traditional feng shui

Traditional feng shui is an ancient system based upon the observation of heavenly time and earthly space. The literature of ancient China, as well as archaeological evidence, provide some idea of the origins and nature of the original feng shui techniques.

Form School

The Form School is the oldest school of feng shui. Qing Wuzi in the Han dynasty describes it in the "Book of the Tomb" and Guo Pu of the Jin dynasty follows up with a more complete description in The Book of Burial.

The Form School was originally concerned with the location and orientation of tombs (Yin House feng shui), which was of great importance.[23] The school then progressed to the consideration of homes and other buildings (Yang House feng shui).

The "form" in Form School refers to the shape of the environment, such as mountains, rivers, plateaus, buildings, and general surroundings. It considers the five celestial animals (phoenix, green dragon, white tiger, black turtle, and the yellow snake), the yin-yang concept and the traditional five elements (Wu Xing: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water).

The Form School analyses the shape of the land and flow of the wind and water to find a place with ideal qi.[49] It also considers the time of important events such as the birth of the resident and the building of the structure.

Compass School

The Compass School is a collection of more recent feng shui techniques based on the eight cardinal directions, each of which is said to have unique qi. It uses the Luopan, a disc marked with formulas in concentric rings around a magnetic compass.[50][51][52]

The Compass School includes techniques such as Flying Star and Eight Mansions.

Transmission of traditional feng shui techniques

Aside from the books written throughout history by feng shui masters and students, there is also a strong oral history. In many cases, masters have passed on their techniques only to selected students or relatives.[53]

Current usage of traditional schools

There is no contemporary agreement that one of the traditional schools is most correct. Therefore, modern practitioners of feng shui generally draw from multiple schools in their own practices.[54]

Western forms of feng shui

More recent forms of feng shui simplify principles that come from the traditional schools, and focus mainly on the use of the bagua.

Aspirations Method

The Eight Life Aspirations style of feng shui is a simple system which coordinates each of the eight cardinal directions with a specific life aspiration or station such as family, wealth, fame, etc., which come from the Bagua government of the eight aspirations. Life Aspirations is not otherwise a geomantic system.

List of specific feng shui schools

Ti Li (Form School)

Popular Xingshi Pai (形势派) "forms" methods

- Luan Tou Pai, 巒頭派, Pinyin: luán tóu pài, (environmental analysis without using a compass)

- Xing Xiang Pai, 形象派 or 形像派, Pinyin: xíng xiàng pài, (Imaging forms)

- Xingfa Pai, 形法派, Pinyin: xíng fǎ pài

Liiqi Pai (Compass School)

Popular Liiqi Pai (理气派) "Compass" methods

San Yuan Method, 三元派 (Pinyin: sān yuán pài)

- Dragon Gate Eight Formation, 龍門八法 (Pinyin: lóng mén bā fǎ)

- Xuan Kong, 玄空 (time and space methods)

- Xuan Kong Fei Xing 玄空飛星 (Flying Stars methods of time and directions)

- Xuan Kong Da Gua, 玄空大卦 ("Secret Decree" or 64 gua relationships)

- Xuan Kong Mi Zi, 玄空秘旨 (Mysterious Space Secret Decree)

- Xuan Kong Liu Fa, 玄空六法 (Mysterious Space Six Techniques)

- Zi Bai Jue, 紫白诀 (Purple White Scroll)

San He Method, 三合派 (environmental analysis using a compass)

- Accessing Dragon Methods

- Ba Zhai, 八宅 (Eight Mansions)

- Yang Gong Feng Shui, 杨公风水

- Water Methods, 河洛水法

- Local Embrace

Others

- Yin House Feng Shui, 阴宅风水 (Feng Shui for the deceased)

- Four Pillars of Destiny, 四柱命理 (a form of hemerology)

- Zi Wei Dou Shu, 紫微斗数 (Purple Star Astrology)

- I-Ching, 易经 (Book of Changes)

- Qi Men Dun Jia, 奇门遁甲 (Mysterious Door Escaping Techniques)

- Da Liu Ren, 大六壬 (Divination: Big Six Heavenly Yang Water Qi)

- Tai Yi Shen Shu, 太乙神数 (Divination: Tai Yi Magical Calculation Method)

- Date Selection, 择日 (Selection of auspicious dates and times for important events)

- Chinese Palmistry, 掌相学 (Destiny reading by palm reading)

- Chinese Face Reading, 面相学 (Destiny reading by face reading)

- Major & Minor Wandering Stars (Constellations)

- Five phases, 五行 (relationship of the five phases or wuxing)

- BTB Black (Hat) Tantric Buddhist Sect (Westernised or Modern methods not based on Classical teachings)

- Symbolic Feng Shui, (new-age Feng Shui methods that advocate substitution with symbolic (spiritual, appropriate representation of five elements) objects if natural environment or object/s is/are not available or viable)

- Pierce Method of Feng Shui ( Sometimes Pronounced : Von Shway ) The practice of melding striking with soothing furniture arrangements to promote peace and prosperity

Contemporary uses of traditional feng shui

- Landscape ecologists often find traditional feng shui an interesting study.[55] In many cases, the only remaining patches of old forest in Asia are "feng shui woods",[56] associated with cultural heritage, historical continuity, and the preservation of various flora and fauna species.[57] Some researchers interpret the presence of these woods as indicators that the "healthy homes",[58] sustainability[59] and environmental components of ancient feng shui should not be easily dismissed.[60][61]

- Environmental scientists and landscape architects have researched traditional feng shui and its methodologies.[62][63][64]

- Architects study feng shui as an ancient and uniquely Asian architectural tradition.[65][66][67][68]

- Geographers have analyzed the techniques and methods to help locate historical sites in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada,[69] and archaeological sites in the American Southwest, concluding that ancient Native Americans also considered astronomy and landscape features.[70]

Criticisms

Traditional feng shui

Traditional feng shui relies upon the compass to give accurate readings. However, critics point out that the compass degrees are often inaccurate as fluctuations caused by solar winds have the ability to greatly disturb the electromagnetic field of the earth. Determining a property or site location based upon Magnetic North will result in inaccuracies because true magnetic north fluctuates.[71]

Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), one of the founding fathers of Jesuit China missions, may have been the first European to write about feng shui practices. His account in De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas... tells about feng shui masters (geologi, in Latin) studying prospective construction sites or grave sites "with reference to the head and the tail and the feet of the particular dragons which are supposed to dwell beneath that spot". As a Catholic missionary, Ricci strongly criticized the "recondite science" of geomancy along with astrology as yet another superstitio absurdissima of the heathens: "What could be more absurd than their imagining that the safety of a family, honors, and their entire existence must depend upon such trifles as a door being opened from one side or another, as rain falling into a courtyard from the right or from the left, a window opened here or there, or one roof being higher than another?".[72]

Victorian-era commentators on feng shui were generally ethnocentric, and as such skeptical and derogatory of what they knew of feng shui.[73] In 1896, at a meeting of the Educational Association of China, Rev. P.W. Pitcher railed at the "rottenness of the whole scheme of Chinese architecture," and urged fellow missionaries "to erect unabashedly Western edifices of several stories and with towering spires in order to destroy nonsense about fung-shuy".[74]

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, feng shui was officially considered a "feudalistic superstitious practice" and a "social evil" according to the state's ideology and was discouraged and even banned outright at times.[75][76] Feng shui remained popular in Hong Kong, and also in the Republic of China (Taiwan), where traditional culture was not suppressed.[77]

Persecution was the most severe during the Cultural Revolution, when feng shui was classified as a custom under the so-called Four Olds to be wiped out. Feng shui practitioners were beaten and abused by Red Guards and their works burned. After the death of Mao Zedong and the end of the Cultural Revolution, the official attitude became more tolerant but restrictions on feng shui practice are still in place in today's China. It is illegal in the PRC today to register feng shui consultation as a business and similarly advertising feng shui practice is banned. There have been frequent crackdowns on feng shui practitioners on the grounds of "promoting feudalistic superstitions" such as one in Qingdao in early 2006 when the city's business and industrial administration office shut down an art gallery converted into a feng shui practice.[78] Some communist officials who had previously consulted feng shui were terminated and expelled from the Communist Party.[79]

Partly because of the Cultural Revolution, in today's mainland China less than one-third of the population believe in feng shui, and the proportion of believers among young urban Chinese is said to be much lower[80] Learning feng shui is still somewhat considered taboo in today's China.[81][82][83] Nevertheless, it is reported that feng shui has gained adherents among Communist Party officials according to a BBC Chinese news commentary in 2006,[84] and since the beginning of Chinese economic reforms the number of feng shui practitioners is increasing. A number of Chinese academics permitted to research on the subject of feng shui are anthropologists or architects by profession, studying the history of feng shui or historical feng shui theories behind the design of heritage buildings, such as Cao Dafeng, the Vice-President of Fudan University,[85] and Liu Shenghuan of Tongji University.

Contemporary feng shui

Westerners were criticized at the start of the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion for violating the basic principles of feng shui in the construction of railroads and other conspicuous public structures throughout China. However, today, feng shui is practiced not only by the Chinese, but also by Westerners and still criticized by Christians around the world. Many modern Christians have an opinion of feng shui similar to that of their predecessors:[86]

It is entirely inconsistent with Christianity to believe that harmony and balance result from the manipulation and channeling of nonphysical forces or energies, or that such can be done by means of the proper placement of physical objects. Such techniques, in fact, belong to the world of sorcery.[87]

Still others are simply skeptical of feng shui. Evidence for its effectiveness is based primarily upon anecdote and users are often offered conflicting advice from different practitioners. Feng shui practitioners use these differences as evidence of variations in practice or different schools of thought. Critical analysts have described it thus: "Feng shui has always been based upon mere guesswork".[88][89] Some are skeptical of feng shui's lasting impact[90] Mark Johnson:[91]

This present state of affairs is ludicrous and confusing. Do we really believe that mirrors and flutes are going to change people's tendencies in any lasting and meaningful way? ... There is a lot of investigation that needs to be done or we will all go down the tubes because of our inability to match our exaggerated claims with lasting changes.

Nonetheless, after Richard Nixon journeyed to the People's Republic of China in 1972, feng shui became marketable in the United States and has since been reinvented by New Age entrepreneurs for Western consumption. Critics of contemporary feng shui are concerned that with the passage of time much of the theory behind it has been lost in translation, not paid proper consideration, frowned upon, or even scorned. Robert T. Carroll sums up what feng shui has become in some instances:

...feng shui has become an aspect of interior decorating in the Western world and alleged masters of feng shui now hire themselves out for hefty sums to tell people such as Donald Trump which way his doors and other things should hang. Feng shui has also become another New Age "energy" scam with arrays of metaphysical products...offered for sale to help you improve your health, maximize your potential, and guarantee fulfillment of some fortune cookie philosophy.[92]

Others have noted how, when feng shui is not applied properly, it can even harm the environment, such as was the case of people planting "lucky bamboo" in ecosystems that could not handle them.[93]

Feng shui practitioners in China find superstitious and corrupt officials easy prey, despite official disapproval. In one instance, in 2009, county officials in Gansu, on the advice of feng shui practitioners, spent $732,000 to haul a 369-ton "spirit rock" to the county seat to ward off "bad luck."[94]

The stage magician duo Penn and Teller dedicated an episode of their Bullshit! television show to criticise the construal of contemporary practice of Feng Shui in the Western World as science. In this episode, they devised a test in which the same dwelling was visited by five different Feng Shui consultants, all five producing different opinions about said dwelling, by which means it was attempted to show there is no consistency in the professional practice of Feng Shui.

Feng shui practice today

Apart from any mystical implications, Feng Shui may be simply understood as a traditional test of architectural goodness using a collection of metaphors. The test may be static or a simulation. Simulations may involve moving an imaginary person or organic creature, such as a dragon of a certain size and flexibility, through a floor plan to uncover awkward turns and cramped spaces before actual construction. This is entirely analogous to imagining how a wheelchair might pass through a building, and is a plausible exercise for architects, who are expected to have exceptional spatial visualization talents. A static test might try to measure comfort in architecture through a ‘hills and valleys’ metaphor. The big hill at your back is a metaphor for security, the open valley and stream represents air and light, and the circle of low hills in front represents both invitation to visitors and your control of your immediate environment. The various Feng Shui tenets represent a set of metaphors that suggest architectural qualities that the average human finds comfortable.

Many Asians, especially people of Chinese descent, believe it is important to live a prosperous and healthy life as evident by the popularity of Fu Lu Shou in the Chinese communities. Many of the higher-level forms of feng shui are not easily practiced without having connections in the community or a certain amount of wealth because hiring an expert, altering architecture or design, and moving from place to place requires a significant financial output. This leads some people of the lower classes to lose faith in feng shui, saying that it is only a game for the wealthy.[95] Others, however, practice less expensive forms of feng shui, including hanging special (but cheap) mirrors, forks, or woks in doorways to deflect negative energy.[96]

In recent years, a new brand of easier-to-implement DIY Feng Shui known as Symbolic Feng Shui, which is popularized by Grandmaster[97] Lillian Too, is being practised by Feng Shui enthusiasts. It entails placements of auspicious (and preferably aesthetically pleasing) Five Element objects, such as Money God and tortoise, at various locations of the house so as to achieve a pleasing and substitute-alternative Productive-Cycle environment if a good natural environment is not already present or is too expensive to build and implement.

Feng shui is so important to some strong believers, that they use it for healing purposes (although there is no empirical evidence that this practice is in any way effective) in addition to guide their businesses and create a peaceful atmosphere in their homes,[98] in particular in the bedroom where a number of techniques involving colours and arrangement are used to achieve enhanced comfort and more peaceful sleep. In 2005, even Disney acknowledged feng shui as an important part of Chinese culture by shifting the main gate to Hong Kong Disneyland by twelve degrees in their building plans, among many other actions suggested by the master planner of architecture and design at Walt Disney Imagineering, Wing Chao, in an effort to incorporate local culture into the theme park.[99]

At Singapore Polytechnic and other institutions, many working professionals from various disciplines (including engineers, architects, property agents and interior designers) take courses on feng shui and divination every year with a number of them becoming part-time or full-time feng shui (or geomancy) consultants eventually.[100]

Feng shui in the Southern Hemisphere

There is a divergence between some feng shui schools on the need or not to adapt the ancient Chinese theories when feng shui is used in the Southern Hemisphere. The differences between the two hemispheres are a fact of reality, but its influence on the feng shui not is unanimity among scholars and practitioners of Chinese technique.

The feng shui schools to the Southern Hemisphere defend the need for changes, that span the feng shui and Chinese Astrology 4 Pillars. Among the main arguments for changes to be made can be cited:

- The "Ba Gua" – octagon with a trigram on each side – is the cycle of the stations. In the Southern Hemisphere the seasons are reversed in relation to the Northern Hemisphere. So the Ba Gua should reflect these differences.

- The "Luo Pan" – Chinese compass with all formulas of feng shui summarized in a grid disc – was created to be used in regions that lack natural elements and landforms. Method of flying stars.

- The Coriolis effect causes the air currents and water rotate in opposite directions in the two hemispheres: counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere This effect causes a mirror in the distribution of energy on the surface of the globe.

- A new perspective, feng shui course, defends the adaptation of the Ba-gua Later Heaven Sequence for the Southern Hemisphere based on trigrams (and its correlation with the seasons) and the Northern Hemisphere Stars guide and the Hemisphere South: Polaris and Alpha-Crux. Feng Shui course created the Solar Method of the Four Seasons, unprecedented and valid method in both hemispheres. This perspective understands the profound Chinese philosophical and updated in Time and Space this important tool to create harmony and prosperity.

The validity of these statements can involve discussions and studies. The following article outlines some reasons and methods used by adopting the adjustments to the Southern Hemisphere.

Feng shui in Brazil ( for example )

The application of feng shui depends on where we are on earth, the place of geography, near a river, where supposedly "energy flows", is moving or near a mountain where energy accumulates. In the case of people: where they are born, where they live.

Speaking in geographical coordinates, east and west remains, plus the equator acts as a mirror dividing Earth into two hemispheres, north and south.

In the Northern Hemisphere cold it is in the north – the Arctic, and the heat in the South the equator. Unlike the Southern Hemisphere where the heat is in the north, the cold is in the south, in Antarctica. The seasons also are reversed. When it is summer in the southern hemisphere, it is winter in the Northern Hemisphere. When it is autumn in the Southern Hemisphere, it is spring in the northern hemisphere, and vice versa. The I Ching mentions that we must turn to the light side, to meditate, i.e. sul in the Northern Hemisphere; which corresponds to turn north in the southern hemisphere. This is based on the position of the sun, which in the southern hemisphere rises in the east, it goes to the north and sets in the west. In the translation of the I Ching for the Portuguese it is also emphasized that one should observe the season referred to in the text and not the month in question, since the work was written in China, which fully meets in the northern hemisphere, and the months corresponding to the seasons are always different in the two hemispheres of the Earth. For example, the sign that represents the height of summer is the horse. Corresponds to heat, fire element, December, toward magnetic north, in the southern hemisphere; while the horse in the northern hemisphere corresponds to the month of June and the south.

The 5 elements (fire / summer, earth, metal / fall, water / winter, wood / spring) are related to the seasons, with directions, with the 12 signs (animals), with the months, days and hours, yielding a calendar.

When working on the floor plan of a building, the technique is used the "Bahzai", and in the case of people the technique of "Min-gua". The 8 trigrams of the I Ching will be related to magnetic coordinates, respectively, in the Southern Hemisphere, it goes for most of Brazil, including São Paulo: North 9, Northeastern 4, East 3, Southeast 8, south 1, Southwest 6, west 7, northwest _se 2 is a matrix (mathematics) 3x3, which is the plan, 360 degrees + (clockwise Northern Hemisphere) or – (anti-clockwise Southern Hemisphere); 5 is in the center, which is the number considered sacred.

| 2 Zhen | 9 Qian | 4 Tui |

| 7 Kan | 5 (69) | 3 Li |

| 6 Ken | 1 Kun | 8 Xun |

"Magic Square"

The relationship between the 12 signs and the five elements originate to 60 binomials. In Summer 2006 is the year of the Metal Dragon in the Southern Hemisphere. The year of change occurs in the 1st Spring Month because the Lunar Year start on Tiger Month 1st Spring, in Summer 2008 is the year of the Water Horse (binomial 19). In 2009 is the Year of the Water Sheep. This date is calculated as the Northern Hemisphere.

See also

References

- 1 2 Field, Stephen L. "The Zangshu, or Book of Burial.".

- ↑ Puro, Jon. "The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience, Volume 2: Feng Shui" (PDF). Antoniolombatti.it. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ Michael Shermer. The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Dunning, Brian. "Feng Shui Today". Skeptoid.com. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ↑ Sun, X. (2000) Crossing the Boundaries between Heaven and Man: Astronomy in Ancient China. In H. Selin (ed.), Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy. 423–54. Kluwer Academic.

- ↑ David W. Pankenier. 'The Political Background of Heaven's Mandate.' Early China 20 (1995): 121-76.

- ↑ Li Liu. The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press (2004) 85–88.

- ↑ Zhentao Xuastronomy. 2000: 2

- ↑ Li Liu. The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press (2004) 248–249.

- ↑ Sarah M. Nelson, Rachel A. Matson, Rachel M. Roberts, Chris Rock and Robert E. Stencel. (2006) Archaeoastronomical Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang. p. 2.

- ↑ Chen Jiujin and Zhang Jingguo. 'Hanshan chutu yupian tuxing shikao,' Wenwu 4, 1989:15

- ↑ Li Liu. The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. Cambridge University Press (2004) 230–37.

- ↑ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China. 2000: 55

- ↑ Feng Shi. Zhongguo zhaoqi xingxiangtu yanjiu. Zhiran kexueshi yanjiu, 2 (1990).

- ↑ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Culture in Early China. 2000: 54-55

- ↑ Cheng Jian Jun and Adriana Fernandes-Gonçalves. Chinese Feng Shui Compass: Step by Step Guide. 1998: 21

- ↑ The Pivot of the Four Quarters (1971: 46)

- ↑ Mark Edward Lewis (2006). The Construction of Space in Early China. p. 275

- ↑ Marc Kalinowski (1996). "The Use of the Twenty-eight Xiu as a Day-Count in Early China." Chinese Science 13 (1996): 55-81.

- ↑ Yin Difei. "Xi-Han Ruyinhou mu chutu de zhanpan he tianwen yiqi." Kaogu 1978.5, 338-43; Yan Dunjie, "Guanyu Xi-Han chuqi de shipan he zhanpan." Kaogu 1978.5, 334-37.

- ↑ Marc Kalinowski. 'The Xingde Texts from Mawangdui.' Early China. 23–24 (1998–99):125–202.

- ↑ Wallace H. Campbell. Earth Magnetism: A Guided Tour Through Magnetic Fields. Academic Press, 2001.

- 1 2 Field, Stephen L. (1998). Qimancy: Chinese Divination by Qi.

- 1 2 3 Bennett, Steven J. (1978) "Patterns of the Sky and Earth: A Chinese Science of Applied Cosmology." Journal of Chinese Science. 3:1–26

- ↑ de Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1892), The Religious System of China, III, Brill Archive, pp. 941–42

- ↑ "Feng Shui". Institute of Feng Shui. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ↑ Tsang ching chien chu (Tse ku chai chung ch'ao, volume 76), p. 1a.

- ↑ "新闻_星岛环球网". stnn.cc.

- ↑ 房山金陵探寻_秦关汉土征未还_洪峰_博联社

- ↑ "凤凰网读书频道". ifeng.com.

- ↑ 蒋介石挖毛泽东祖坟的玄机

- ↑ 丧心病狂中国历史上六宗罕见的辱尸事

- ↑ Field, Stephen L. (1998). Qimancy: The Art and Science of Fengshui.

- ↑ Lui, A.T.Y., Y. Zheng, Y. Zhang, H. Rème, M.W. Dunlop, G. Gustafsson, S.B. Mende, C. Mouikis, and L.M. Kistler, Cluster observation of plasma flow reversal in the magnetotail during a substorm, Ann. Geophys., 24, 2005-2013, 2006

- ↑ Max Knoll. "Transformations of Science in Our Age." In Joseph Campbell (ed.). Man and Time. Princeton UP, 1957, 264–306.

- ↑ Wallace Hall Campbell. Earth Magnetism: A Guided Tour through Magnetic Fields. Harcourt Academic Press. 2001:55

- ↑ "֤s". fushantang.com.

- ↑ 韩信

- ↑ 地理与天理

- ↑ "文章". fengshui-magazine.com.hk.

- ↑ Sarah Allan. The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art and Cosmos in Early China. 1991:31–32.

- ↑ Werner, E. T. C. Myths and Legends of China. London Bombay Sydney: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd. p. 84. ISBN 0-486-28092-6. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ↑ Frank J. Swetz (2002). The Legacy of the Luoshu. pp. 31, 58.

- ↑ Frank J. Swetz (2002). Legacy of the Luoshu. p. 36–37

- ↑ Deborah Lynn Porter. From Deluge to Discourse. 1996:35–38.

- 1 2 Sun and Kistemaker. The Chinese Sky During the Han. 1997:15–18.

- ↑ Aihe Wang. Cosmology and Political Structure in Early China. 2000: 107–28

- ↑ Sarah M. Nelson, Rachel A. Matson, Rachel M. Roberts, Chris Rock, and Robert E. Stencel. Archaeoastronomical Evidence for Wuism at the Hongshan Site of Niuheliang. 2006

- ↑ Moran, Yu, Biktashev (2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Feng Shui. Pearson Education.

- ↑ "Feng Shui Schools". Feng Shui Natural. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ Cheng Jian Jun and Adriana Fernandes-Gonçalves. Chinese Feng Shui Compass Step by Step Guide. 1998:46–47

- ↑ MoonChin. Chinese Metaphysics: Essential Feng Shui Basics. ISBN 978-983-43773-1-1

- ↑ Cheung Ngam Fung, Jacky (2007). "History of Feng Shui". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ↑ "Feng Shui Schools". Feng Shui Natural. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ Bo-Chul Whang and Myung-Woo Lee. Landscape ecology planning principles in Korean Feng-Shui, Bi-bo woodlands and ponds. J. Landscape and Ecological Engineering. 2:2, November, 2006. 147–62.

- ↑ Chen, Bixia (February 2008). A Comparative Study on the Feng Shui Village Landscape and Feng Shui Trees in East Asia (PDF) (PhD dissertation). United Graduate School of Agricultural Sciences, Kagoshima University (Japan).

- ↑ Marafa L. "Integrating natural and cultural heritage: the advantage of feng shui landscape resources". International Journal of Heritage Studies, Volume 9, Number 4, December 2003, pp. 307–23(17)

- ↑ Qigao Chen, Ya Feng, Gonglu Wang. Healthy Buildings Have Existed in China Since Ancient Times. Indoor and Built Environment, 6:3, 179–87 (1997)

- ↑ Stephen Siu-Yiu Lau, Renato Garcia, Ying-Qing Ou, Man-Mo Kwok, Ying Zhang, Shao Jie Shen, Hitomi Namba. Sustainable design in its simplest form: Lessons from the living villages of Fujian rammed earth houses. Structural Survey. 2005, 23:5, 371–85

- ↑ Xue Ying Zhuang, Richard T. Corlett. Forest and Forest Succession in Hong Kong, China. J. of Tropical Ecology. 13:6 (Nov. 1997), 857

- ↑ Marafa, L. M. Integrating Natural and Cultural Heritage: the advantage of feng shui landscape resources. Intl. J. Heritage Studies. 2003, 9: Part 4, 307–24

- ↑ Chen, B. X. and Nakama, Y. A summary of research history on Chinese Feng-shui and application of feng shui principles to environmental issues. Kyusyu J. For. Res. 57. 297–301 (2004).

- ↑ Xu, Jun. 2003. A framework for site analysis with emphasis on feng shui and contemporary environmental design principles. Blacksburg, Va: University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- ↑ Lu, Hui-Chen. 2002. A Comparative analysis between western-based environmental design and feng-shui for housing sites. Thesis (M.S.). California Polytechnic State University, 2002.

- ↑ Park, C.-P. Furukawa, N. Yamada, M. A Study on the Spatial Composition of Folk Houses and Village in Taiwan for the Geomancy (Feng-Shui). J. Arch. Institute of Korea. 1996, 12:9 129–40.

- ↑ Xu, P. Feng-Shui Models Structured Traditional Beijing Courtyard Houses. J. Architectural and Planning Research. 1998, 15:4 271–82.

- ↑ Hwangbo, A. B. An Alternative Tradition in Architecture: Conceptions in Feng Shui and Its Continuous Tradition. J. Architectural and Planning Research. 2002, 19:2 pp. 110–30.

- ↑ Su-Ju Lu; Peter Blundell Jones. House design by surname in Feng Shui. J. of Architecture. 5:4 December 2000, 355–67.

- ↑ Chuen-Yan David Lai. A Feng Shui Model as a Location Index. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64 (4), 506-513.

- ↑ Xu, P. Feng-shui as Clue: Identifying Ancient Indian Landscape Setting Patterns in the American Southwest. Landscape Journal. 1997, 16:2, 174–90.

- ↑ "Earth's Inconstant Magnetic Field". NASA Science. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci", Random House, New York, 1953. Book One, Chapter 9, pp. 84–85. This text appears in pp. 103–04 of Book One of the original Latin text by Ricci and Nicolas Trigault, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu

- ↑ Andrew L. March. 'An Appreciation of Chinese Geomancy' in The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No. 2. (February 1968), pp. 253–67.

- ↑ Jeffrey W. Cody. Striking a Harmonious Chord: Foreign Missionaries and Chinese-style Buildings, 1911–1949. Architronic. 5:3 (ISSN 1066-6516)

- ↑ "Chang Liang (pseudoym), 14 January 2005, What Does Superstitious Belief of 'Feng Shui' Among School Students Reveal?". Zjc.zjol.com.cn. 2005-01-31. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ Tao Shilong, 3 April 2006, The Crooked Evil of 'Feng Shui' Is Corrupting The Minds of Chinese People

- ↑ Moore, Malcolm (2010-12-16). "Hong Kong government spends millions on feng shui". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ Chen Xintang Art Gallery Shut by the Municipality's Business and Industrial Department After Converting to 'Feng Shui' Consultation Office Banduo Daoxi Bao, Qingdao, January 19, 2006 Archived April 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ ""風水迷信"困擾中國當局 – Feng Shui Superstitions Troubles Chinese Authorities". BBC News. 9 March 2001. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ Debate on Feng Shui

- ↑ "Beware of Scams Among the Genuine Feng Shui Practitioners". Jiugu861sohu.blog.sohu.com. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ "ˮȨɽ--Ļ--". people.com.cn.

- ↑ "方术之国". newmind40.com.

- ↑ Jiang Xun (11 April 2006). "Focus on China From Voodoo Dolls to Feng Shui Superstitions" (in Chinese). BBC Chinese service. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ "蔡达峰 – Cao Dafeng". Fudan.edu.cn. Archived from the original on 2012-05-09. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ Mah, Y.-B. Living in Harmony with One's Environment: A Christian Response to Feng Shui. Asia J. of Theology. 2004, 18; Part 2, pp 340–361.

- ↑ Marcia Montenegro. Feng Shui" New Dimensions in Design. Christian Research Journal. 26:1 (2003)

- ↑ Edwin Joshua Dukes, The Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, T & T Clark, Edinburgh, 1971, p 834

- ↑ Monty Vierra. Harried by "Hellions" in Taiwan. Sceptical Briefs newsletter, March 1997.

- ↑ Jane Mulcock. Creativity and Politics in the Cultural Supermarket: synthesizing indigenous identities for the r-evolution of spirit. Continuum. 15:2. July 2001, 169–85.

- ↑ "Reality Testing in Feng Shui." Qi Journal. Spring 1997

- ↑ Carroll, Robert T. "feng shui". The Skeptic's Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ Elizabeth Hilts, "Fabulous Feng Shui: It's Certainly Popular, But is it Eco-Friendly?" E Magazine

- ↑ Dan Levin (May 10, 2013). "China Officials Seek Career Shortcut With Feng Shui". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ↑ Emmons, C. F. "Hong Kong's Feng Shui: Popular Magic in a Modern Urban Setting." Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 1992, p. 42

- ↑ Emmons, C. F. "Hong Kong's Feng Shui: Popular Magic in a Modern Urban Setting." Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 1992, p. 46

- ↑ http://www.intfsa.org/IFSC2009writeup.pdf International Feng Shui Convention 2009 Singapore Management University 21 & 22 November 2009

- ↑ Emmons, C. F. "Hong Kong's Feng Shui: Popular Magic in a Modern Urban Setting." Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 1992, p. 48

- ↑ Laura M. Holson, "The Feng Shui Kingdom"

- ↑ "Feng Shui course gains popularity". Asiaone.com. 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

Further reading

- Ernest John Eitel (1878). Feng-shui: or, The rudiments of natural science in China. Hongkong: Lane, Crawford. Retrieved 2011-07-06.

- Koch, Master Aaron Lee. Feng Shui Q&A. 8 Feng Shui Publishing, 2014. ISBN 978-1-312-61845-9.

- Ole Bruun. "Fengshui and the Chinese Perception of Nature", in Asian Perceptions of Nature: A Critical Approach, eds. Ole Bruun and Arne Kalland (Surrey: Curzon, 1995) 173–88.

- Ole Bruun. An Introduction to Feng Shui. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Ole Bruun. Fengshui in China: Geomantic Divination between State Orthodoxy and Popular Religion. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2003.

- Yoon, Hong-key. Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy. Lexington Books, 2006.

- Xie, Shan Shan. Chinese Geographic Feng Shui Theories and Practices. National Multi-Attribute Institute Publishing, Oct. 2008. ISBN 1-59261-004-8.

- Charvatova, I., Klokocnik, J., Kolmas, J., & Kostelecky, J. (2011). Chinese tombs oriented by a compass: Evidence from paleomagnetic changes versus the age of tombs. Studia Geophysica Et Geodaetica, 55(1), 159–74. doi:10.1007/s11200-011-0009-2. Abstract: "Extant written records indicate that knowledge of an ancient type of compass in China is very old – dating back to before the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) to at least the 4th century BC. Geomancy (feng shui) was practised for a long time (for millennia) and had a profound influence on the face of China's landscape and city plans. The tombs (pyramids) near the former Chinese capital cities of Xi'an and Luoyang (together with their suburban fields and roads) show strong spatial orientations, sometimes along a basic South-North axis (relative to the geographic pole), but usually with deviations of several degrees to the East or West. The use of the compass means that the needle was directed towards the actual magnetic pole at the time of construction, or last reconstruction, of the respective tomb. However the magnetic pole, relative to the nearly 'fixed' geographic pole, shifts significantly over time. By matching paleomagnetic observations with modeled paleomagnetic history we have identified the date of pyramid construction in central China with the orientation relative to the magnetic pole positions at the respective time of construction. As in Mesoamerica, where according to the Fuson hypothesis the Olmecs and Maya oriented their ceremonial buildings and pyramids using a compass even before the Chinese, here in central China the same technique may have been used. We found a good agreement of trends between the paleodeclinations observed from tomb alignments and the available global geomagnetic field model CALS7K.2."

- Chen, X., & Wu, J. (2009). Sustainable landscape architecture: Implications of the Chinese philosophy of 'unity of man with nature' and beyond. Landscape Ecology, 24(8), 1015–26. doi:10.1007/s10980-009-9350-z

- Lacroix, R., & Stamatiou, E. (2006). Feng shui and spatial planning for a better quality of life. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development, 2(5), 578–83. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/290374661

- Kereszturi, A., & Sik, A. (2000). Feng-shui on mars; history of geomorphological effects of water and wind. Abstracts of Papers Submitted to the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, 31, abstr. no. 1216

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Feng Shui. |