James's flamingo

| James' flamingo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Phoenicopteriformes |

| Family: | Phoenicopteridae |

| Genus: | Phoenicoparrus |

| Species: | P. jamesi |

| Binomial name | |

| Phoenicoparrus jamesi (Sclater, 1886)[2] | |

The James's flamingo (Phoenicoparrus jamesi), also known as the puna flamingo, is a species of flamingo that populates the high altitudes of Andean plateaus of Peru, Chile, Bolivia and Argentina.

It is named for Harry Berkeley James, a British naturalist who studied the bird. James's flamingo is closely related to the Andean flamingo, and the two make up the genus Phoenicoparrus. The Chilean flamingo, Andean flamingo and James's flamingo are all sympatric, and all live in colonies (including shared nesting areas).[3] The James's flamingo was thought to have been extinct until a remote population was discovered in 1956.[4]

Description

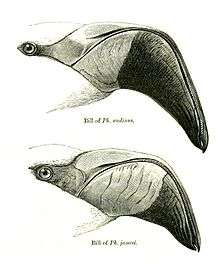

James's flamingo is smaller than the Andean flamingo, and is about the same size as the Old World species, the lesser flamingo. A specimen of the bird was first collected by Charles Rahmer who was on a collecting expedition sponsored by Harry Berkley James after whom the bird was named.[5] It measures about 90–92 centimetres (2 ft 11 in–3 ft 0 in) long on average and weighs about 2 kilograms (4.4 lb).[6] The James's flamingo have a very long neck that is made up of 19 long cervical vertebrae allowing for a lot of movement and rotation of the head.[7] Their long thin legs also characterize them. The knee is not visible externally but is located at the top of the leg. The joint at the middle of the leg, which most assume to be the knee joint is actually the ankle joint. Its plumage is very pale pink, with bright carmine streaks around the neck and on the back. When perched a small amount of black can be seen in the wings, these are the flight feathers. There is bright red skin around the eyes, which are yellow in adults. The legs are brick red and the bill is bright yellow with a black tip. James's flamingo is similar to other South American flamingos, but the Chilean flamingo is pinker, with a longer bill without yellow, and the Andean flamingo is larger with more black in the wings and bill, and yellow legs. The easiest method to distinguish James's flamingos is by the lighter feathers and the bright yellow on the bill. A good method to distinguish Phoenicoparrus from the other species is to look at the feet. In the other three species of flamingos the feet consist of three forward-facing toes and a hallux. The two species of Phoenicoparrus have the three toes but do not have a hallux.[7]

Feathers

Newly hatched flamingos are gray or white. They gain color after 2 or 3 years of age. The active component that gives the feathers the pink color is the proteins alpha and beta-carotene (similar to carotene in carrots). A diet rich in carotene allows them to produce pigmented feathers.[8] An adult has 12 main feathers designed for flight on each wing. The body is covered in contour feathers, which protect the bird and also help with waterproofing from a secretion of oil at the base of the feather. When roosting they face the wind so that if it rains the rain does not get up and under the feathers. Plumage is pale pink, with bright carmine streaks around the neck and on the back. When perched a small amount of black can be seen in the wings, these are the flight feathers mentioned above. There are typically 12 to 16 tail feathers. James's flamingos molt their wing and body feathers according to their breeding schedule and the color of the new feathers depends on the quality of the diet that they have obtained. There is no evidence of color differentiation between the males and females.

Flight

Although in zoos flamingos usually appear stationary, they are able to fly. They have specific feathers used to take flight. These feathers are easily distinguished in James's flamingo's because they're the only black feathers on the bird.[7] In order to begin flying they run a few steps and then begin to flap their wings. When they want to land, the opposite process occurs and as they touch down to a surface they continue to run as they decelerate they stop flapping their wings. Flamingos have been noted to fly up to 37 miles per hour (60 km/h). This measurement refers to a migration of an entire flock but there is evidence that due to the limited regions in which this species is found, they do not migrate very far and therefore, may not reach this speed when going shorter distances.[9]

Ecology

Feeding

Both the James's and Andean flamingos feed their chicks through an esophageal secretion that is regurgitated from the crop of the bird.[10] The difference between the two species lies in the composition of the prolactin secretion produced by each bird. Both male and female parents are able to feed the chick. Adult flamingos are the most developed filter feeders of the birds. Of the species, James's flamingo has the finest filter feeding apparatus.[11] The flamingo feeds on diatoms and other microscopic algae.[3] The shape of the bill is deep keeled. To feed, the flamingos' long legs allow them to walk into the water and swoop their necks down into an S-shape to allow the beak to enter the water. The S-shape is effective because it allows the head to be placed upright and the bottom of the bill to be placed as shallow or as deep as it pleases. By only lowering the distal end of the bill into the water it allows nostrils to remain above water. The water filled with small organisms floods the bill and filtration process begins. The lakes, which the flamingo typically feeds from, are Andean lakes which are mostly freshwater,[12] but if salt water is encountered, the flamingos have salt glands in their nostrils where excess salt is secreted. The filtering process starts with the tongue, which is very soft and fleshy with channel like features that direct the food and water to the filtering apparatus. The bill of James's flamingo is the narrowest of its kind. Both the Andean and James's flamingos have deep-keeled bills where the upper jaw is narrower than the lower. The gape of the bill is therefore on the dorsal side of the bill. The bill of James's flamingo is smaller and has a narrower upper jaw. The proximal end of the bill is mostly horizontal then there is a curvature downward and the distal end finishes with a hook-like feature. The inner morphology of the beak is similar to that of the lesser flamingo, where the upper and lower jaws contain lamellae which filter the food. In both the upper and lower jaw, the proximal portion of the bill contains lamellae that are ridge-like and as you approach the curvature and distal end they become more like hooks. There are marginal and submarginal lamellae and James's flamingo has the greatest number of both which also means there is a smaller intermarginal distance between them. There are 21 lamellae per cm in this species, which is more than twice the amount found in other flamingos. When the upper and lower jaws close together the lamellae mesh together to allow the bill to be closed fully.[13] The sizes of the diatoms associated with this size filtering apparatus are anywhere from 21-60 μm. Diatoms this size are typically found close to the edge of the water, it has been shown that even in colonies of multiple species the James's flamingos typically feed in the region closest to the edge of the water. The birds are able to use their webbed feet to help kick up microscopic algae if there is not enough floating in the water column.[3]

Breeding

Breeding cycles in flamingos begin at 6 years of age when fully matured. The frequency of breeding is irregular and may skip a year. It is not unusual for the entire colony to participate in mating rituals at the same time. The males put on a show by vocalizing and sticking their necks and heads straight up in the air and turning their heads back and forth. The female initiates the mating by walking away from the group and the male follows. The female then spreads her wings and the male mounts the female.[7] The female lays one egg on a volcano shaped nest made from mud, sticks, and other materials in the environment. The shape of the egg is oval, similar to that of a chicken. It is smaller in size (length and breadth) compared to the other species including the closely related Andean flamingo.[4] Both the male and female incubate the egg for 26–31 days before it hatches. The chick breaks through the shell using an egg tooth, which is not actually a true tooth but is actually a keratinized structure, which falls off after fully hatching. When newly hatched, the chick's bill is straight and red but later develops a curve and the adult colored beak. The feathers are white and grey and the legs are pink. The eyes of chicks are gray for its first year. The parents are able to distinguish their chick from others in the colony by appearance and vocalization.[7]

Conservation status

This species was determined to be near threatened by the IUCN in 2008. This classification was because the populations of the last three generations of this species has declined. The flamingo has since shown improvements which may be due to a less threatening environment.

The biggest threat to the population of this species is human destruction of their habitat. In local cultures it was common practice to steal the eggs from the nest and sell them but since then measures have been taken in order to control this. Environmental threats such as heavy rainfall may also have an effect on the breeding of the species. Anything that threatens the productivity of the diatoms also threatens the species if there is not enough food for them to eat.

See also

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Phoenicoparrus jamesi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Sclater, PL (1886). "List of a Collection of Birds from the Province of Tarapaca, Northern Chili": 395–404.

- 1 2 3 Mascitti, V. and Kravetz, F.O., "Bill Morphology of South American Flamingos". The Condor. 104(1), 73.

- 1 2 Johnson, A.W., Behn, F., and Millie, W.R. "The South American Flamingos". The Condor. 60(5), 289-99

- ↑ Mabbett, Andy (2006-08-04). "James' Flamingo and Walsall". RSPB Walsall Local Group. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ↑ "Puna flamingo videos, photos and facts – Phoenicoparrus jamesi – ARKive". arkive.org.

- 1 2 3 4 5 SeaWorld Parks & Entertainment. "Flamingos". seaworld.org.

- ↑ Jenkin, P.M. "The Filter-Feeding and Food of Flamingoes (Phoenicopter)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 240(674), 401-493.

- ↑ Johnson, A.W., Behn, F., and Millie, W.R. "The South American Flamingos".The Condor.60(5), 289-99

- ↑ Sabat, P. and Novoa, F.F. "Digestive Constraints and Nutrient Hydrolysis in Nestlings of Two Flamingo Species". The Condor. 103(2), 396.

- ↑ Conway, William G. "CARE OF JAMES'S FLAMINGO Phoenicoparrus jamesi Sclater AND THE ANDEAN FLAMINGO Phoenicoparrus andinus R. A. Philippi IN CAPTIVITY". International Zoo Yearbook. 5(1), 162-164

- ↑ "Birding Alto Andino". birdingaltoandino.com.

- ↑ Jenkin, P.M. "The Filter-Feeding and Food of Flamingoes (Phoenicopter)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 240(674), 401-493.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phoenicoparrus jamesi. |

- Puna Flamingo from the IUCN/Wetlands International Flamingo Specialist Group

- James's flamingo media at ARKive

- Flamingo Resource Centre – a collection of resources and information related to flamingos

- Fauna of Atacama – image of James's Flamingo

- Harry Berkeley James and his Flamingo