Pulsed laser deposition

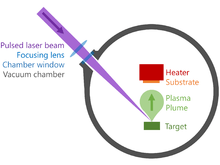

Pulsed laser deposition (PLD) is a physical vapor deposition (PVD) technique where a high-power pulsed laser beam is focused inside a vacuum chamber to strike a target of the material that is to be deposited. This material is vaporized from the target (in a plasma plume) which deposits it as a thin film on a substrate (such as a silicon wafer facing the target). This process can occur in ultra high vacuum or in the presence of a background gas, such as oxygen which is commonly used when depositing oxides to fully oxygenate the deposited films.

While the basic setup is simple relative to many other deposition techniques, the physical phenomena of laser-target interaction and film growth are quite complex (see Process below). When the laser pulse is absorbed by the target, energy is first converted to electronic excitation and then into thermal, chemical and mechanical energy resulting in evaporation, ablation, plasma formation and even exfoliation.[1] The ejected species expand into the surrounding vacuum in the form of a plume containing many energetic species including atoms, molecules, electrons, ions, clusters, particulates and molten globules, before depositing on the typically hot substrate.

Process

The detailed mechanisms of PLD are very complex including the ablation process of the target material by the laser irradiation, the development of a plasma plume with high energetic ions, electrons as well as neutrals and the crystalline growth of the film itself on the heated substrate. The process of PLD can generally be divided into five stages:

- Laser absorption on the target surface

- Laser ablation of the target material and creation of a plasma

- Dynamic of the plasma

- Deposition of the ablation material on the substrate

- Nucleation and growth of the film on the substrate surface

Each of these steps is crucial for the crystallinity, uniformity and stoichiometry of the resulting film. The mostly used methods for modelling the PLD process are the Monte Carlo techniques.[2]

Laser ablation of the target material and creation of a plasma

The ablation of the target material upon laser irradiation and the creation of plasma are very complex processes. The removal of atoms from the bulk material is done by vaporization of the bulk at the surface region in a state of non-equilibrium. In this the incident laser pulse penetrates into the surface of the material within the penetration depth. This dimension is dependent on the laser wavelength and the index of refraction of the target material at the applied laser wavelength and is typically in the region of 10 nm for most materials. The strong electrical field generated by the laser light is sufficiently strong to remove the electrons from the bulk material of the penetrated volume. This process occurs within 10 ps of a ns laser pulse and is caused by non-linear processes such as multiphoton ionization which are enhanced by microscopic cracks at the surface, voids, and nodules, which increase the electric field. The free electrons oscillate within the electromagnetic field of the laser light and can collide with the atoms of the bulk material thus transferring some of their energy to the lattice of the target material within the surface region. The surface of the target is then heated up and the material is vaporized.

Dynamic of the plasma

In the second stage the material expands in a plasma parallel to the normal vector of the target surface towards the substrate due to Coulomb repulsion and recoil from the target surface. The spatial distribution of the plume is dependent on the background pressure inside the PLD chamber. The density of the plume can be described by a cosn(x) law with a shape similar to a Gaussian curve. The dependency of the plume shape on the pressure can be described in three stages:

- The vacuum stage, where the plume is very narrow and forward directed; almost no scattering occurs with the background gases.

- The intermediate region where a splitting of the high energetic ions from the less energetic species can be observed. The time-of-flight (TOF) data can be fitted to a shock wave model; however, other models could also be possible.

- High pressure region where we find a more diffusion-like expansion of the ablated material. Naturally this scattering is also dependent on the mass of the background gas and can influence the stoichiometry of the deposited film.

The most important consequence of increasing the background pressure is the slowing down of the high energetic species in the expanding plasma plume. It has been shown that particles with kinetic energies around 50 eV can resputter the film already deposited on the substrate. This results in a lower deposition rate and can furthermore result in a change in the stoichiometry of the film.

Deposition of the ablation material on the substrate

The third stage is important to determine the quality of the deposited films. The high energetic species ablated from the target are bombarding the substrate surface and may cause damage to the surface by sputtering off atoms from the surface but also by causing defect formation in the deposited film.[3] The sputtered species from the substrate and the particles emitted from the target form a collision region, which serves as a source for condensation of particles. When the condensation rate is high enough, a thermal equilibrium can be reached and the film grows on the substrate surface at the expense of the direct flow of ablation particles and the thermal equilibrium obtained.

Nucleation and growth of the film on the substrate surface

The nucleation process and growth kinetics of the film depend on several growth parameters including:

- Laser parameters – several factors such as the laser fluence [Joule/cm2], laser energy, and ionization degree of the ablated material will affect the film quality, the stoichiometry,[4] and the deposition flux. Generally, the nucleation density increases when the deposition flux is increased.

- Surface temperature – The surface temperature has a large effect on the nucleation density. Generally, the nucleation density decreases as the temperature is increased.[5] Heating of the surface can involve a heating plate or the use of a CO2 laser.[6]

- Substrate surface – The nucleation and growth can be affected by the surface preparation (such as chemical etching[7]), the miscut of the substrate, as well as the roughness of the substrate.

- Background pressure – Common in oxide deposition, an oxygen background is needed to ensure stoichiometric transfer from the target to the film. If, for example, the oxygen background is too low, the film will grow off stoichiometry which will affect the nucleation density and film quality.[8]

In PLD, a large supersaturation occurs on the substrate during the pulse duration. The pulse lasts around 10–40 microseconds[9] depending on the laser parameters. This high supersaturation causes a very large nucleation density on the surface as compared to molecular beam epitaxy or sputtering deposition. This nucleation density increases the smoothness of the deposited film.

In PLD, [depending on the deposition parameters above] three growth modes are possible:

- Step-flow growth – All substrates have a miscut associated with the crystal. These miscuts give rise to atomic steps on the surface. In step-flow growth, atoms land on the surface and diffuse to a step edge before they have a chance to nucleated a surface island. The growing surface is viewed as steps traveling across the surface. This growth mode is obtained by deposition on a high miscut substrate, or depositing at elevated temperatures[10]

- Layer-by-layer growth – In this growth mode, islands nucleate on the surface until a critical island density is reached. As more material is added, the islands continue to grow until the islands begin to run into each other. This is known as coalescence. Once coalescence is reached, the surface has a large density of pits. When additional material is added to the surface the atoms diffuse into these pits to complete the layer. This process is repeated for each subsequent layer.

- 3D growth – This mode is similar to the layer-by-layer growth, except that once an island is formed an additional island will nucleate on top of the 1st island. Therefore, the growth does not persist in a layer by layer fashion, and the surface roughens each time material is added.

History

Pulsed laser deposition is only one of many thin film deposition techniques. Other methods include molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), sputter deposition (RF, magnetron, and ion beam). The history of laser-assisted film growth started soon after the technical realization of the first laser in 1960 by Maiman. Smith and Turner utilized a ruby laser to deposit the first thin films in 1965, three years after Breech and Cross studied the laser-vaporization and excitation of atoms from solid surfaces. However, the deposited films were still inferior to those obtained by other techniques such as chemical vapor deposition and molecular beam epitaxy. In the early 1980s, a few research groups (mainly in the former USSR) achieved remarkable results on manufacturing of thin film structures utilizing laser technology. The breakthrough came in 1987 when Dijkkamp, Xindi Wu and Venkatesan were able to laser deposit a thin film of YBa2Cu3O7, a high temperature superconductive material, which was of superior quality to that of films deposited with alternative techniques. Since then, the technique of pulsed laser deposition has been utilized to fabricate high quality crystalline films, such as doped garnet thin films for use as planar waveguide lasers.[11] The deposition of ceramic oxides, nitride films, metallic multilayers and various superlattices has been demonstrated. In the 1990s the development of new laser technology, such as lasers with high repetition rate and short pulse durations, made PLD a very competitive tool for the growth of thin, well defined films with complex stoichiometry.

Technical aspects

There are many different arrangements to build a deposition chamber for PLD. The target material which is evaporated by the laser is normally found as a rotating disc attached to a support. However, it can also be sintered into a cylindrical rod with rotational motion and a translational up and down movement along its axis. This special configuration allows not only the utilization of a synchronized reactive gas pulse but also of a multicomponent target rod with which films of different multilayers can be created.

Some factors that influence the deposition rate:

- Target material

- Pulse energy of laser

- Distance from target to substrate

- Type of gas and pressure in chamber (oxygen, argon, etc.)

References

- ↑ Pulsed Laser Deposition of Thin Films, edited by Douglas B. Chrisey and Graham K. Hubler, John Wiley & Sons, 1994 ISBN 0-471-59218-8

- ↑ Rashidian Vaziri, M R (2011). "Monte Carlo simulation of the subsurface growth mode during pulsed laser deposition". Journal of Applied Physics. 110 (4): 043304. doi:10.1063/1.3624768.

- ↑ Vaziri, M R R (2010). "Microscopic description of the thermalization process during pulsed laser deposition of aluminium in the presence of argon background gas". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 43 (42): 425205. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/43/42/425205.

- ↑ Ohnishi, Tsuyoshi; Shibuya, Keisuke; Yamamoto, Takahisa; Lippmaa, Mikk (2008). "Defects and transport in complex oxide thin films". Journal of Applied Physics. 103 (10): 103703. Bibcode:2008JAP...103j3703O. doi:10.1063/1.2921972.

- ↑ Ferguson, J. D.; Arikan, G.; Dale, D. S.; Woll, A. R.; Brock, J. D. (2009). "Measurements of Surface Diffusivity and Coarsening during Pulsed Laser Deposition". Physical Review Letters. 103 (25): 256103. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.103y6103F. PMID 20366266. arXiv:0910.3601

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.256103.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.256103. - ↑ May-Smith, T. C.; Muir, A. C.; Darby, M. S. B.; Eason, R. W. (2008-04-10). "Design and performance of a ZnSe tetra-prism for homogeneous substrate heating using a CO2 laser for pulsed laser deposition experiments". Applied Optics. 47 (11): 1767–1780. ISSN 1539-4522. doi:10.1364/AO.47.001767.

- ↑ Koster, Gertjan; Kropman, Boike L.; Rijnders, Guus J. H. M.; Blank, Dave H. A.; Rogalla, Horst (1998). "Quasi-ideal strontium titanate crystal surfaces through formation of strontium hydroxide". Applied Physics Letters. 73 (20): 2920. Bibcode:1998ApPhL..73.2920K. doi:10.1063/1.122630.

- ↑ Ohtomo, A.; Hwang, H. Y. (2007). "Growth mode control of the free carrier density in SrTiO[sub 3−δ] films". Journal of Applied Physics. 102 (8): 083704. Bibcode:2007JAP...102h3704O. arXiv:cond-mat/0604117

. doi:10.1063/1.2798385.

. doi:10.1063/1.2798385. - ↑ Granozio, F. M. et al. In-situ Investigation of Surface Oxygen Vacancies in Perovskites Mat. Res. Soc. Proc. 967E, (2006)

- ↑ Lippmaa, M.; Nakagawa, N.; Kawasaki, M.; Ohashi, S.; Koinuma, H. (2000). "Growth mode mapping of SrTiO[sub 3] epitaxy". Applied Physics Letters. 76 (17): 2439. Bibcode:2000ApPhL..76.2439L. doi:10.1063/1.126369.

- ↑ Grant-Jacob, James A.; Beecher, Stephen J.; Parsonage, Tina L.; Hua, Ping; Mackenzie, Jacob I.; Shepherd, David P.; Eason, Robert W. (2016-01-01). "An 115 W Yb:YAG planar waveguide laser fabricated via pulsed laser deposition". Optical Materials Express. 6 (1): 91. ISSN 2159-3930. doi:10.1364/ome.6.000091.

External links

- Introduction to Pulsed Laser Deposition Introduction to Pulsed laser deposition

- Laser-MBE: Pulsed Laser Deposition under Ultra-High Vacuum

- Pérez Taborda, Jaime Andrés; Caicedo, J.C.; Grisales, M.; Saldarriaga, W.; Riascos, H. (2015). "Deposition pressure effect on chemical, morphological and optical properties of binary Al-nitrides". Optics & Laser Technology. 69: 92. Bibcode:2015OptLT..69...92P. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2014.12.009.

- A Brief Overview of Pulse Laser Deposition System