CCL18

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18 (CCL18) is a small cytokine belonging to the CC chemokine family. The functions of CCL18 have been well studied in laboratory settings, however the physiological effects of the molecule in living organisms have been difficult to characterize because there is no similar protein in rodents that can be studied. The receptor for CCL18 has been identified in humans only recently, which will help scientists understand the molecule's role in the body.

CCL18 is produced and secreted mainly by innate immune system, and has effects mainly on the adaptive immune system. It was previously known as Pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine (PARC), dendritic cell (DC)-chemokine 1 (DC-CK1), alternative macrophage activation-associated CC chemokine-1 (AMAC-1), and macrophage inflammatory protein-4 (MIP-4).

Gene and protein structure

The gene of CCL18 is most similar to CCL3.[2] CCL18 is located on chromosome 17, along with many other macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIPs). The gene itself has 3 exons and 2 introns; but, unlike other chemokines, CCL18 includes 2 pseudo-exons (exons that do not appear in the final peptide) in the first intron.[3] Because of these pseudo-exons, it is believed that CCL18 arose as a result of a gene fusion event between CCL3-like protein encoding genes and gained a different function over time due to accumulating mutations.[3][4] CCL18 is a 89 peptide-long protein, with a 20 peptide signalling sequence (to signal its secretion) at the N’ terminus which is cleaved in the endoplasmic reticulum into a 69 peptide mature protein.[2]

Sources

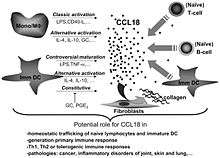

CCL18 is produced mainly by antigen-presenting cells of the innate immune system. These cells include dendritic cells, monocytes, and macrophages.[6][7][8] Neither T-cells nor B-cells are known to produce CCL18.[6] Its production is upregulated in these cells by IL-10, IL-4, and IL-13, which are cytokines that favour a T-helper 2 type response and are generally involved in humoral immunity or for immunosuppression. The presence of IFN-gamma, a T-helper 1 type response cytokine important for cell-mediated immunity, dampens the production of CCL18.[9] Furthermore, CCL18 is induced by fibroblasts, specifically by induction of collagen produced by fibroblasts, which is important in tissue healing and repair.[8] Finally, CCL18 is constitutively and highly expressed in the lungs, suggesting that CCL18 plays role in maintaining homeostasis.

Chemotactic functions

Chemokines are classed as a special type of cytokine that is involved in immune cell trafficking. CCL18 in particular has some chemotactic functions for the innate immune system, but its functions are primarily involved with recruitment of the adaptive immune system. CCL18 is involved in attracting naïve T-cells,[10] T-regulatory cells,[6][11] T-helper 2 cells,[12] both immunosuppressive and immature Dendritic Cells,[6][9] basophils,[12] and B-cells (naïve and effector).[5] The T-regulatory cells that CCL18 attracts are not classical T-regulatory cells; these cells do not express FoxP3 as most T-regulatory cells do, and instead non-antigen specifically exert their immunosuppressive functions by secreting IL-10.[8] It is thought that these recruited cells maintain homeostasis under healthy conditions.

Receptor

The classical receptors for chemokines are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), which have 7 transmembrane regions. Following this trend, it was thought that CCL18’s receptor is also probably a GPCR. However, for a long time, the physiological receptor has not been found until very recently. To date, are three receptors that have been proposed for CCL18: PITPNM3, GPR30, and CCR8. PITPNM3 is a CCL18 receptor, but PITPNM3 is only expressed on breast cancer cells and not on T-cells nor B-cells, and PITPNM3-CCL8 binding induces Pyk2 and Src mediated signaling, a cancer related signaling pathway, and subsequent metastasis of breast cancer.[13][14] GPR30 is also reported to bind to CCL18, but binding of CCL18 does not induce chemotaxis; instead, binding of CCL18 to GPR30 blocks both activation of GPR30 by its natural ligands and reduces the ability of CXCL12-dependant activation of acute lymphocytic leukemia B cells.[15] CCR8 is the most recently discovered receptor for CCL18, and the effects of CCR8-CCL18 interactions appear to be physiological, as CCL18 binding to CCR8 induces chemotaxis of Th2 cells.[16] Furthermore, CCL18 binding is competitive with CCR8’s previously described ligand, CCL1, further suggesting that CCL18 binds physiologically with CCR8.[16]) Further elucidation of the role of CCR8 in CCL18-mediated pathologies would allow for better understanding of CCL18’s function in these diseases.

Effector functions

CCL18 has a plethora of functions that have been characterized in vitro and in vivo. Strangely, CCL18 seems to play a part in both activation of the immune system and the induction of tolerance and homeostasis at steady-state conditions.

Immune activation

The production of CCL18 is induced by T-helper 2 type cytokines, namely IL-4 and IL-13. Coupled with the fact that CCL18 is highly expressed in patients with allergic asthma[17] and other hypersensitivity diseases,[5] CCL18 seems to play an important role for generating and maintaining a T-helper 2 (Th2) type response. Furthermore, the addition of CCL18 as an adjuvant for a malaria vaccine have shown efficacy, perhaps by recruiting immune cells to the site of vaccination.[18] Finally, CCL18 is expressed by dendritic cells in the germinal center of inflamed lymph nodes, and recruits naïve B-cells for antigen presentation.[19] Perhaps aberrant CCL18 expression is involved in the generation of chronic Th2 response, leading to asthma or arthritis.

Immunosuppression

In addition to immune-activating effects, CCL18 also has strong immunosuppressive effects. CCL18 induces immature dendritic cells to differentiate into an immunosuppressive dendritic cell that is capable producing CCL18 which attract T-cells, suppressing effector T-cell function, and generating T-regulatory cells by secreting large amounts of IL-10.[9][20] Furthermore, exposure to CCL18 by macrophages causes them to mature in the #M2 spectrum, which promotes immunosuppression and healing.[8]

Involvement in disease

Aberrant CCL18 expression is observed in many diseases, and it is thought that these abnormal expression patterns play a key role in these diseases.[5] This table shows a list of all the diseases that CCL18 is involved in.

Breast cancer

The most understood disease that CCL18 is involved in is in breast cancer, where CCL18 induces metastasis of breast cancer cells by binding to PITPNM3.[14] Perhaps CCL18, in breast cancers, is acting as an immunosuppressive cytokine by generating T-regulatory cells, generating immunosuppressive dendritic cells and macrophages, and recruiting effector T-cells to these dendritic cells and macrophages to abolish their anti-cancer functions and allowing the cancer to escape the immune system.

Autoimmunity and hypersensitivity

CCL18 is highly expressed in T-helper 2 mediated hypersensitivity and autoimmune diseases, such as asthma and arthritis.[12] CCL18 is expressed at much higher levels in allergic patients compared to healthy patients and respond aggressively to innocuous antigens.[12] Allergic patients also had higher amounts of activated T-cells in the lungs, suggesting that CCL18 recruitment of these cells is contributing to hypersensitivity. In addition to lung hypersensitivities, these patterns were also observed in dermatitis patients.[5] Furthermore, a similar pattern was also observed in arthritis patients, where CCL18 was expressed at much higher rates by dendritic cells in affected patients.[21] However, in arthritis, perhaps the increased CCL18 is an attempt to suppress effector T-helper 1 cells that are self-reactive.

References

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- 1 2 Hieshima K, Imai T, Baba M, Shoudai K, Ishizuka K, Nakagawa T, Tsuruta J, Takeya M, Sakaki Y, Takatsuki K, Miura R, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Yoshie O, Nomiyama H (August 1997). "A novel human CC chemokine PARC that is most homologous to macrophage-inflammatory protein-1 alpha/LD78 alpha and chemotactic for T lymphocytes, but not for monocytes". J. Immunol. 159 (3): 1140–9. PMID 9233607.

- 1 2 Politz O, Kodelja V, Guillot P, Orfanos CE, Goerdt S (February 2000). "Pseudoexons and regulatory elements in the genomic sequence of the beta-chemokine, alternative macrophage activation-associated CC-chemokine (AMAC)-1". Cytokine. 12 (2): 120–6. PMID 10671296. doi:10.1006/cyto.1999.0538.

- ↑ Tasaki Y, Fukuda S, Iio M, Miura R, Imai T, Sugano S, Yoshie O, Hughes AL, Nomiyama H (February 1999). "Chemokine PARC gene (SCYA18) generated by fusion of two MIP-1alpha/LD78alpha-like genes". Genomics. 55 (3): 353–7. PMID 10049593. doi:10.1006/geno.1998.5670.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schutyser E, Richmond A, Van Damme J (July 2005). "Involvement of CC chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18) in normal and pathological processes". J. Leukoc. Biol. 78 (1): 14–26. PMC 2665283

. PMID 15784687. doi:10.1189/jlb.1204712.

. PMID 15784687. doi:10.1189/jlb.1204712. - 1 2 3 4 Bellinghausen I, Reuter S, Martin H, Maxeiner J, Luxemburger U, Türeci Ö, Grabbe S, Taube C, Saloga J (December 2012). "Enhanced production of CCL18 by tolerogenic dendritic cells is associated with inhibition of allergic airway reactivity". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 130 (6): 1384–93. PMID 23102918. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.039.

- ↑ Ferrara G, Bleck B, Richeldi L, Reibman J, Fabbri LM, Rom WN, Condos R (December 2008). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces CCL18 expression in human macrophages". Scand. J. Immunol. 68 (6): 668–74. PMID 18959625. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02182.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Schraufstatter IU, Zhao M, Khaldoyanidi SK, Discipio RG (April 2012). "The chemokine CCL18 causes maturation of cultured monocytes to macrophages in the M2 spectrum". Immunology. 135 (4): 287–98. PMC 3372745

. PMID 22117697. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03541.x.

. PMID 22117697. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03541.x. - 1 2 3 Vulcano M, Struyf S, Scapini P, Cassatella M, Bernasconi S, Bonecchi R, Calleri A, Penna G, Adorini L, Luini W, Mantovani A, Van Damme J, Sozzani S (April 2003). "Unique regulation of CCL18 production by maturing dendritic cells". J. Immunol. 170 (7): 3843–9. PMID 12646652. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3843.

- ↑ Adema GJ, Hartgers F, Verstraten R, de Vries E, Marland G, Menon S, Foster J, Xu Y, Nooyen P, McClanahan T, Bacon KB, Figdor CG (June 1997). "A dendritic-cell-derived C-C chemokine that preferentially attracts naive T cells". Nature. 387 (6634): 713–7. PMID 9192897. doi:10.1038/42716.

- ↑ Chenivesse C, Chang Y, Azzaoui I, Ait Yahia S, Morales O, Plé C, Foussat A, Tonnel AB, Delhem N, Yssel H, Vorng H, Wallaert B, Tsicopoulos A (July 2012). "Pulmonary CCL18 recruits human regulatory T cells". J. Immunol. 189 (1): 128–37. PMID 22649201. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003616.

- 1 2 3 4 de Nadaï P, Charbonnier AS, Chenivesse C, Sénéchal S, Fournier C, Gilet J, Vorng H, Chang Y, Gosset P, Wallaert B, Tonnel AB, Lassalle P, Tsicopoulos A (May 2006). "Involvement of CCL18 in allergic asthma". J. Immunol. 176 (10): 6286–93. PMID 16670340. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6286.

- ↑ Li HY, Cui XY, Wu W, Yu FY, Yao HR, Liu Q, Chen JQ (October 2013). "Pyk2 and Src mediate signaling to CCL18-induced breast cancer metastasis". J. Cell. Biochem. 115: 596–603. PMID 24142406. doi:10.1002/jcb.24697.

- 1 2 Chen J, Yao Y, Gong C, Yu F, Su S, Chen J, Liu B, Deng H, Wang F, Lin L, Yao H, Su F, Anderson KS, Liu Q, Ewen ME, Yao X, Song E (April 2011). "CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis via PITPNM3". Cancer Cell. 19 (4): 541–55. PMC 3107500

. PMID 21481794. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.006.

. PMID 21481794. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.006. - ↑ Catusse J, Wollner S, Leick M, Schröttner P, Schraufstätter I, Burger M (November 2010). "Attenuation of CXCR4 responses by CCL18 in acute lymphocytic leukemia B cells". J. Cell. Physiol. 225 (3): 792–800. PMID 20568229. doi:10.1002/jcp.22284.

- 1 2 Islam SA, Ling MF, Leung J, Shreffler WG, Luster AD (September 2013). "Identification of human CCR8 as a CCL18 receptor". J. Exp. Med. 210 (10): 1889–98. PMC 3782048

. PMID 23999500. doi:10.1084/jem.20130240.

. PMID 23999500. doi:10.1084/jem.20130240. - ↑ Kodelja V, Müller C, Politz O, Hakij N, Orfanos CE, Goerdt S (February 1998). "Alternative macrophage activation-associated CC-chemokine-1, a novel structural homologue of macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha with a Th2-associated expression pattern". J. Immunol. 160 (3): 1411–8. PMID 9570561.

- ↑ Bruna-Romero O, Schmieg J, Del Val M, Buschle M, Tsuji M (March 2003). "The dendritic cell-specific chemokine, dendritic cell-derived CC chemokine 1, enhances protective cell-mediated immunity to murine malaria". J. Immunol. 170 (6): 3195–203. PMID 12626578. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3195.

- ↑ Lindhout E, Vissers JL, Hartgers FC, Huijbens RJ, Scharenborg NM, Figdor CG, Adema GJ (March 2001). "The dendritic cell-specific CC-chemokine DC-CK1 is expressed by germinal center dendritic cells and attracts CD38-negative mantle zone B lymphocytes". J. Immunol. 166 (5): 3284–9. PMID 11207283. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3284.

- ↑ Azzaoui I, Yahia SA, Chang Y, Vorng H, Morales O, Fan Y, Delhem N, Ple C, Tonnel AB, Wallaert B, Tsicopoulos A (September 2011). "CCL18 differentiates dendritic cells in tolerogenic cells able to prime regulatory T cells in healthy subjects". Blood. 118 (13): 3549–58. PMID 21803856. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-02-338780.

- ↑ Radstake TR, van der Voort R, ten Brummelhuis M, de Waal Malefijt M, Looman M, Figdor CG, van den Berg WB, Barrera P, Adema GJ (March 2005). "Increased expression of CCL18, CCL19, and CCL17 by dendritic cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and regulation by Fc gamma receptors". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64 (3): 359–67. PMC 1755402

. PMID 15331393. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.017566.

. PMID 15331393. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.017566.

External links

- Human CCL18 genome location and CCL18 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.