Pullman Strike

| Pullman Strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

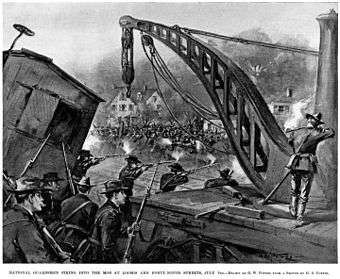

Striking American Railway Union members confront Illinois National Guard troops in Chicago during the Pullman Strike | |||

| Date | May 11, 1894 | ||

| Location | Began in Pullman, Chicago; spread throughout the United States | ||

| Goals | Recognition | ||

| Methods | Strikes, Protest, Demonstrations | ||

| Resulted in | Unsuccessful | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

|

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| |||

The Pullman Strike was a nationwide railroad strike in the United States on May 11, 1894, and a turning point for US labor law. It pitted the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman Company, the main railroads, and the federal government of the United States under President Grover Cleveland. The strike and boycott shut down much of the nation's freight and passenger traffic west of Detroit, Michigan. The conflict began in Pullman, Chicago, on May 11 when nearly 4,000 factory employees of the Pullman Company began a wildcat strike in response to recent reductions in wages.

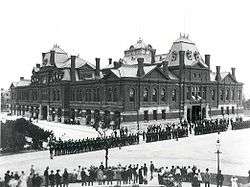

Most factory workers who built Pullman cars lived in the "company town" of Pullman on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois.[1] The industrialist George Pullman had designed it ostensibly as a model community.[1] Pullman had a diverse work force. He wanted to hire African-Americans for certain jobs at the company. Pullman used ads and other campaigns to help bring workers into his company.[2]

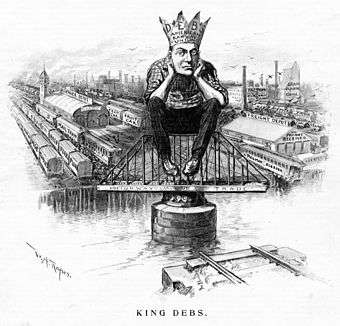

When his company laid off workers and lowered wages, it did not reduce rents, and the workers called for a strike. Among the reasons for the strike were the absence of democracy within the town of Pullman and its politics, the rigid paternalistic control of the workers by the company, excessive water and gas rates, and a refusal by the company to allow workers to buy and own houses. They had not yet formed a union.[1] Founded in 1893 by Eugene V. Debs, the ARU was an organization of unskilled railroad workers. Debs brought in ARU organizers to Pullman and signed up many of the disgruntled factory workers.[1] When the Pullman Company refused recognition of the ARU or any negotiations, ARU called a strike against the factory, but it showed no sign of success. To win the strike, Debs decided to stop the movement of Pullman cars on railroads. The over-the-rail Pullman employees (such as conductors and porters) did not go on strike.[1]

Debs and the ARU called a massive boycott against all trains that carried a Pullman car. It affected most rail lines west of Detroit and at its peak involved some 250,000 workers in 27 states. The Railroad brotherhoods and the American Federation of Labor (AFL) opposed the boycott, and the General Managers Association of the railroads coordinated the opposition. Thirty people were killed in response to riots and sabotage that caused $80 million in damages.[3][4] The federal government obtained an injunction against the union, Debs, and other boycott leaders, ordering them to stop interfering with trains that carried mail cars. After the strikers refused, President Grover Cleveland ordered in the Army to stop the strikers from obstructing the trains. Violence broke out in many cities, and the strike collapsed. Defended by a team including Clarence Darrow, Debs was convicted of violating a court order and sentenced to prison; the ARU then dissolved.

Background

During a severe depression (the Panic of 1893), the Pullman Palace Car Company cut wages as demand for new passenger cars plummeted and the company's revenue dropped. A delegation of workers complained that wages had been cut but not rents at their company housing or other costs in the company town. The company owner, George Pullman, refused to lower rents or go to arbitration.[5]

Boycott

Many of the Pullman factory workers joined the American Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene V. Debs, which supported their strike by launching a boycott in which ARU members refused to run trains containing Pullman cars. The plan was to force the railroads to bring Pullman to compromise. Debs began the boycott on June 26, 1894. Within four days, 125,000 workers on twenty-nine railroads had "walked off" the job rather than handle Pullman cars.[6] The railroads coordinated their response through the General Managers' Association, which had been formed in 1886 and included 24 lines linked to Chicago.[7][8] The railroads began hiring replacement workers (strikebreakers), which increased hostilities. Many blacks were recruited as strikebreakers and crossed picket lines, as they feared that the racism expressed by the American Railway Union would lock them out of another labor market. This added racial tension to the union's predicament.[9]

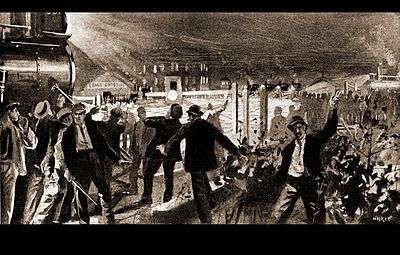

On June 29, 1894, Debs hosted a peaceful meeting to rally support for the strike from railroad workers at Blue Island, Illinois. Afterward, groups within the crowd became enraged and set fire to nearby buildings and derailed a locomotive.[10] Elsewhere in the western states, sympathy strikers prevented transportation of goods by walking off the job, obstructing railroad tracks, or threatening and attacking strikebreakers. This increased national attention and the demand for federal action.

Federal intervention

Under direction from President Grover Cleveland, the US Attorney General Richard Olney dealt with the strike. Olney had been a railroad attorney, and still received a $10,000 retainer from the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, in comparison to his $8,000 salary as Attorney General.[11] Olney obtained an injunction in federal court barring union leaders from supporting the strike and demanding that the strikers cease their activities or face being fired. Debs and other leaders of the ARU ignored the injunction, and federal troops were called up to enforce it.[12] While Debs had been reluctant to start the strike, he threw his energies into organizing it. He called a general strike of all union members in Chicago, but this was opposed by Samuel Gompers, head of the AFL, and other established unions, and it failed.[13]

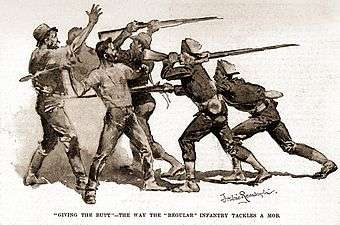

City by city the federal forces broke the ARU efforts to shut down the national transportation system. Thousands of United States Marshals and some 12,000 United States Army troops, commanded by Brigadier General Nelson Miles, took action. President Cleveland wanted the trains moving again, based on his legal, constitutional responsibility for the mails. His lawyers argued that the boycott violated the Sherman Antitrust Act, and represented a threat to public safety. The arrival of the military and the subsequent deaths of workers in violence led to further outbreaks of violence. During the course of the strike, 30 strikers were killed and 57 were wounded. Property damage exceeded $80 million.[3][4][14]

Local responses

The strike affected hundreds of towns and cities across the country. Railroad workers were divided, for the old established Brotherhoods, which included the skilled workers such as engineers, firemen and conductors, did not support the labor action. ARU members did support the action, and often comprised unskilled ground crews. In many areas townspeople and businessmen generally supported the railroads while farmers—many affiliated with the Populists—supported the ARU.

In Billings, Montana, an important rail center, a local Methodist minister, J. W. Jennings, supported the ARU. In a sermon he compared the Pullman boycott to the Boston Tea Party, and attacked Montana state officials and President Cleveland for abandoning "the faith of the Jacksonian fathers."[15] Rather than defending "the rights of the people against aggression and oppressive corporations," he said party leaders were "the pliant tools of the codfish monied aristocracy who seek to dominate this country."[15] Billings remained quiet but on July 10, soldiers reached Lockwood, Montana, a small rail center, where the troop train was surrounded by hundreds of angry strikers. Narrowly averting violence, the army opened the lines through Montana. When the strike ended, the railroads fired and blacklisted all the employees who had supported it.[16]

In California the boycott was effective in Sacramento, a labor stronghold, but weak in the Bay Area and minimal in Los Angeles. The strike lingered as strikers expressed longstanding grievances over wage reductions, and indicate how unpopular the Southern Pacific Railroad was. Strikers engaged in violence and sabotage; the companies saw it as civil war while the ARU proclaimed it was a crusade for the rights of unskilled workers.[17]

Public opinion

Public opinion was mostly opposed to the strike and supported Cleveland's actions.[18] Republicans and eastern Democrats supported Cleveland (the leader of the northeastern pro-business wing of the party), but southern and western Democrats as well as Populists generally denounced him. Governor John Peter Altgeld of Illinois, a Democrat, denounced Cleveland and said he could handle all disturbances in his state without federal intervention.[19]

Media coverage was extensive and generally negative. A common trope in news reports and editorials depicted the boycotters as foreigners who contested the patriotism expressed by the militias and troops involved, as numerous recent immigrants worked in the factories and on the railroads. The editors warned of mobs, aliens, anarchy, and defiance of the law.[20] The New York Times called it "a struggle between the greatest and most important labor organization and the entire railroad capital."[21] In Chicago the established church leaders denounced the boycott, but some younger Protestant ministers defended it.[22]

Aftermath

Debs was arrested on federal charges, including conspiracy to obstruct the mail as well as disobeying an order directed to him by the Supreme Court to stop the obstruction of railways and to dissolve the boycott. He was defended by Clarence Darrow, a prominent attorney, as well as Lyman Trumbull. At the conspiracy trial Darrow argued that it was the railways, not Debs and his union, that met in secret and conspired against their opponents. Sensing that Debs would be acquitted, the prosecution dropped the charge when a juror took ill. Although Darrow also represented Debs at the United States Supreme Court for violating the federal injunction, Debs was sentenced to six months in prison.[23]

Early in 1895 General William M. Graham erected a memorial obelisk in the San Francisco National Cemetery at the Presidio, in honor of four soldiers of the 5th Artillery killed in a Sacramento train crash of July 11, 1894, during the strike. The train wrecked crossing a trestle bridge purportedly dynamited by union members.[24] Graham's monument included the inscription, "Murdered by Strikers", a description he hotly defended.[25] The obelisk remains in place.

In the aftermath of the Pullman strike, the state ordered the company to sell off its residential holdings. In the decades after Pullman died (1897), Pullman became just another South Side neighborhood. It remained the area’s largest employer before closing in the 1950s. The area is both a National Historic Landmark as well as a Chicago Landmark District. Because of the significance of the strike, many state agencies and non-profit groups are hoping for many revivals of the Pullman neighborhoods starting with Pullman Park, one of the largest projects. It was to be a $350 million mixed used development on the site of an old steel plant. The plan was for 670,000 square feet of new retail space, 125,000 square foot neighborhood recreation center and 1,100 housing units. (source: Historical NY Times)

Politics

Following his release from jail in 1895, ARU President Debs became a committed advocate of socialism, helping in 1897 to launch the Social Democracy of America, a forerunner of the Socialist Party of America. He ran for president in 1900 for the first of five times as head of the Socialist Party ticket.

Civil as well as criminal charges were brought against the organizers of the strike and Debs in particular, and the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision, In re Debs, that rejected Debs' actions. The Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld was incensed at Cleveland for putting the federal government at the service of the employers, and for rejecting Altgeld's plan to use his state militia rather than federal troops to keep order.[26]

Cleveland's administration appointed a national commission to study the causes of the 1894 strike; it found George Pullman's paternalism partly to blame and described the operations of his company town to be "un-American". In 1898, the Illinois Supreme Court forced the Pullman Company to divest ownership in the town, as its company charter did not authorize such operations, and the land was annexed to Chicago.[27] Much of it is now designated as an historic district, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Labor Day

In 1894, in an effort to conciliate organized labor after the strike, President Grover Cleveland and Congress designated Labor Day as a federal holiday. Legislation for the holiday was pushed through Congress six days after the strike ended. Samuel Gompers, who had sided with the federal government in its effort to end the strike by the American Railway Union, spoke out in favor of the holiday.[28][29]

See also

- United States labor law

- History of rail transport in the United States

- Murder of workers in labor disputes in the United States

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Pullman Strike and Boycott," Annals of American History. <http://www.america.eb.com/america/article?articleId=386364&query=pullman+strike> [Accessed January 24, 2014].

- ↑ Ayres, Tim, and Susan Eleanor Hirsch. "After the Strike: A Century of Labor Struggle at Pullman." Labour History, 2003, 280.

- 1 2 Ray Ginger, Eugene V. Debs (1962) p 170

- 1 2 Papke, David Ray (1999). The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America. Landmark law cases & American society. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. pp. 35–37. ISBN 0-7006-0954-7.

- ↑ Joseph C. Bigott (2001). From Cottage to Bungalow: Houses and the Working Class in Metropolitan Chicago, 1869–1929. U. of Chicago Press. p. 93. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016.

- ↑ Richard Schneirov; Shelton Stromquist; Nick Salvatore (1999). The Pullman Strike and Crisis of 1890s: Essays on Labor and Politics. U. of Illinois Press. p. 137. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016.

- ↑ Wish, "The Pullman Strike"

- ↑ Donald L. McMurry, "Labor Policies of the General Managers' Association of Chicago, 1886–1894," Journal of Economic History (1953) 13#2 pp. 160–178 in JSTOR Archived June 21, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ David E. Bernstein, Only One Place of Redress (2001) p. 54

- ↑ Harvey Wish, "The Pullman Strike: A Study in Industrial Warfare," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1939) 32#3, pp. 288–312 in JSTOR Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ↑ Eric Arnesen (2004). The Human Tradition in American Labor History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 96. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016.

- ↑ Salvatore, Debs pp 134–37

- ↑ John R. Commons; et al. (1918). History of Labour in the United States vol 2. Macmillan. p. 502. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Carroll Van West, Capitalism on the Frontier: Billings and the Yellowstone Valley in the Nineteenth Century (1993) p 200

- ↑ Van West, Capitalism on the Frontier: Billings and the Yellowstone Valley in the Nineteenth Century, p 200

- ↑ William W. Ray, "Crusade or Civil War? The Pullman Strike in California," California History (1979) 58#1 pp 20–37.

- ↑ Allan Nevins, Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage (1933) pp. 624–7

- ↑ H.W. Brands (2002). The Reckless Decade: America in the 1890s. U. of Chicago Press. p. 153. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016.

- ↑ Troy Rondinone, "Guarding the Switch: Cultivating Nationalism during the Pullman Strike," Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (2009) 8#1 pp 83–109.

- ↑ Donald L. Miller (1997). City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America. Simon and Schuster. p. 543. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016.

- ↑ Heath W. Carter, "Scab Ministers, Striking Saints: Christianity and Class Conflict in 1894 Chicago," American Nineteenth Century History (2010) 11#3 pp 321–349

- ↑ John A. Farrell (2011). Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 69–72. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016.

- ↑ Leach, Frank A. "The Great Railroad Strike of 1894". U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 2, 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ "General Graham Writes of Treason" (PDF). San Francisco Call via Library of Congress. 22 August 1895. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ↑ Peter Zavodnyik (2011). The Rise of the Federal Colossus: The Growth of Federal Power from Lincoln to F.D.R. ABC-CLIO. pp. 233–34. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016.

- ↑ Dennis R. Judd; Paul Kantor (1992). Enduring tensions in urban politics. Macmillan. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Online NewsHour: Origins of Labor Day – September 2, 1996". PBS. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ↑ Bill Haywood, The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, 1929, p. 78 ppbk.

Sources

- Cleveland, Grover. The Government and the Chicago Strike of 1894 [1904]. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1913.

- DeForest, Walter S. The Periodical Press and the Pullman Strike: An Analysis of the Coverage and Interpretation of the Railroad Strike of 1894 by Eight Journals of Opinion and Reportage MA thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1973.

- Ginger, Ray. The Bending Cross: A Biography of Eugene V. Debs. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1949.

- Hirsch, Susan Eleanor. After the Strike: A Century of Labor Struggle at Pullman. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

- Lindsey, Almont. The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and of a Great Labor Upheaval. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1943.

- Lindsey, Almont. "Paternalism and the Pullman Strike," American Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Jan., 1939), pp. 272–289 in JSTOR

- Nevins, Allan Nevins. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage. (1933) pp. 611–28

- Papke, David Ray. The Pullman Case: The Clash of Labor and Capital in Industrial America. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1999.

- Rondinone, Troy. "Guarding the Switch: Cultivating Nationalism During the Pullman Strike," Journal of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era 2009 8(1): 83–109 27p.

- Salvatore, Nick. Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1984.

- Schneirov, Richard, et al. (eds.) The Pullman Strike and the Crisis of the 1890s: Essays on Labor and Politics. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

- Smith, Carl. Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief: The Great Chicago Fire, the Haymarket Bomb, and the Model Town of Pullman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Winston, A.P. "The Significance of the Pullman Strike," Journal of Political Economy, vol. 9, no. 4 (Sept. 1901), pp. 540–561. In JSTOR

- Wish, Harvey. "The Pullman Strike: A Study in Industrial Warfare," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1939) 32#3 pp. 288–312 in JSTOR

Primary sources

- United States Strike Commission, Report on the Chicago Strike of June–July, 1894. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pullman Strike. |

- Pullman Strike Timeline

- Chicago Strike

- The Pullman Strike, Illinois During the Gilded Age 1866–1894, Illinois Historical Digitization Projects at Northern Illinois University Libraries