Cry of Pugad Lawin

| Cry of Pugad Lawin Cry of Balintawak | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philippine Revolution | |||||||

.jpg) Bonifacio Monument | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

The Cry of Pugad Lawin (Filipino: Sigaw ng Pugad Lawin), alternately and originally referred to as the Cry of Balintawak (Filipino: Sigaw ng Balíntawak, Spanish: Grito de Balíntawak), was the beginning of the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire.[1]

At the close of August 1896, members of the Katipunan secret society (Katipuneros) led by Andrés Bonifacio rose up in revolt somewhere in an area referred to as Caloocan,[2] wider than the jurisdiction of present-day Caloocan City which may have overlapped into present-day Quezon City.[3]

Originally the term "Cry" referred to the first clash between the Katipuneros and the Civil Guards (Guardia Civil). The cry could also refer to the tearing up of community tax certificates (cédulas personales) in defiance of their allegiance to Spain. This was literally accompanied by patriotic shouts.[4]

Because of competing accounts and ambiguity of the place where this event took place, the exact date and place of the Cry is in contention.[3][4] From 1908 until 1963, the official stance was that the Cry occurred on August 26 in Balintawak. In 1963 the Philippine government declared a shift to August 23 in Pugad Lawin, Quezon City.[4]

Different dates and places

Various accounts give differing dates and places for the Cry. An officer of the Spanish guardia civil, Lt. Olegario Diaz, stated that the Cry took place in Balintawak on August 25, 1896. Historian Teodoro Kalaw in his 1925 book The Filipino Revolution wrote that the event took place during the last week of August 1896 at Kangkong, Balintawak. Santiago Alvarez, a Katipunero and son of Mariano Alvarez, the leader of the Magdiwang faction in Cavite, stated in 1927 that the Cry took place in Bahay Toro, now in Quezon City on August 24, 1896. Pío Valenzuela, a close associate of Andrés Bonifacio, declared in 1948 that it happened in Pugad Lawin on August 23, 1896. Historian Gregorio Zaide stated in his books in 1954 that the "Cry" happened in Balintawak on August 26, 1896. Fellow historian Teodoro Agoncillo wrote in 1956 that it took place in Pugad Lawin on August 23, 1896, based on Pío Valenzuela's statement. Accounts by historians Milagros Guerrero, Emmanuel Encarnacion and Ramon Villegas claim the event to have taken place in Tandang Sora's barn in Gulod, Barangay Banlat, Quezon City.[5][6]

Some of the apparent confusion is in part due to the double meanings of the terms "Balintawak" and "Caloocan" at the turn of the century. Balintawak referred both to a specific place in modern Caloocan City and a wider area which included parts of modern Quezon City. Similarly, Caloocan referred to modern Caloocan City and also a wider area which included modern Quezon City and part of modern Pasig. Pugad Lawin, Pasong Tamo, Kangkong and other specific places were all in "greater Balintawak", which was in turn part of "greater Caloocan".[3][4]

Definition of the Cry

The term "Cry" is translated from the Spanish el grito de rebelion (cry of rebellion) or el grito for short. Thus the Grito de Balintawak is comparable to Mexico's Grito de Dolores (1810). However, el grito de rebelion strictly refers to a decision or call to revolt. It does not necessarily connote shouting, unlike the Filipino sigaw.[3][4]

First skirmish

Up to the late 1920s, the Cry was generally identified with Balintawak. It was commemorated on August 26, considered the anniversary of the first hostile encounter between the Katipuneros and the Guardia Civil. The "first shot" of the Revolution (el primer tiro) was fired at Banlat, Pasong Tamo, then considered a part of Balintawak and now part of Quezon City.[4]

Tearing of cédulas

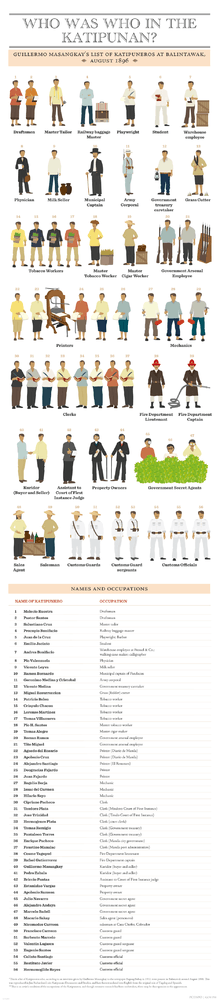

Not all accounts relate the tearing of cédulas in the last days of August. Of the accounts that do, older ones identify the place where this occurred as Kangkong in Balintawak/Kalookan. Most also give the date of the cédula-tearing as August 26, in close proximity to the first encounter. One Katipunero, Guillermo Masangkay, claimed cédulas were torn more than once – on the 24th as well as the 26th.[4]

For his 1956 book The Revolt of the Masses Teodoro Agoncillo defined "the Cry" as the tearing of cedulas, departing from precedent which had then defined it as the first skirmish of the revolution. His version was based on the later testimonies of Pío Valenzuela and others who claimed the cry took place in Pugad Lawin instead of Balintawak. Valenzuela's version, through Agoncillo's influence, became the basis of the current stance of the Philippine government. In 1963, President Diosdado Macapagal ordered the official commemorations shifted to Pugad Lawin, Quezon City on August 23.[4]

Formation of an insurgent government

An alternative definition of the Cry as the "birth of the Filipino nation state" involves the setting up of a national insurgent government through the Katipunan with Bonifacio as President in Banlat, Pasong Tamo on August 24, 1896 – after the tearing of cedulas but before the first skirmish. This was called the Haring Bayang Katagalugan (Sovereign Tagalog Nation).[3]

Other Cries

In 1895 Bonifacio, Masangkay, Emilio Jacinto and other Katipuneros spent Good Friday in the caves of Mt. Pamitinan in Montalban (now part of Rizal province). They wrote "long live Philippine independence" on the cave walls, which some Filipino historians consider the "first cry" (el primer grito).[4]

Commemoration

The Cry is commemorated as National Heroes' Day, a public holiday in the Philippines.[7]

The first annual commemoration of the Cry occurred in Balintawak in 1908 after the American colonial government repealed the Sedition Law. In 1911 a monument to the Cry (a lone Katipunero popularly identified with Bonifacio) was erected at Balintawak; it was later transferred to Vinzons Hall in the University of the Philippines-Diliman, Quezon City. In 1984, the National Historical Institute of the Philippines installed a commemorative plaque in Pugad Lawin.[4]

References

- ↑ Sichrovsky, Harry. "An Austrian Life for the Philippines:The Cry of Balintawak". Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ Ocampo, Ambeth R. (1995). Bonifacio's bolo. Anvil Pub. p. 8. ISBN 978-971-27-0418-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Guerrero, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (1996), "Balintawak: the Cry for a Nationwide Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 1 (2): 13–22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Borromeo-Buehler, Soledad M. (1998), The cry of Balintawak: a contrived controversy : a textual analysis with appended documents, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-278-8.

- ↑ Duka, Cecilio D. (2008). Struggle for Freedom: A Textbook on Philippine History. Rex Book Store, Inc. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- ↑ "Come August, Remember Balintawak". Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- ↑ "Monday holiday remembers historic "Cry of Balintawak"". Retrieved 2009-08-29.

Further reading

- Soledad Masangkay Borromeo (1998). The Cry of Balintawak: A Contrived Controversy : a Textual Analysis with Appended Documents. Ateneo University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-278-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cry of Pugad Lawin. |

- Andres Bonifacio The Eve Of St. Bartholomew

- The Cry of Pugad Lawin

- National Historical Institute: Celebrating National Heroes Day