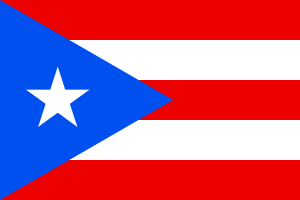

Flag of Puerto Rico

| |

| Name | Current flag of Puerto Rico |

|---|---|

| Adopted | 1952 |

|

Variant flag of Puerto Rico | |

| Name | (1895 flag version with Azul Celeste blue tone) |

|

Variant flag of Puerto Rico | |

| Name | (1952 flag version with dark blue tone) |

| Use | Civil and state flag, civil and state ensign |

| Design | Five equal horizontal bands of red (top and bottom) alternating with white; blue ) isosceles triangle based on the hoist side bears a large, white, five-pointed star in the center.(Official colors of the flag) |

The flag of Puerto Rico represents and symbolizes the island of Puerto Rico and its people.

The origins of the current flag of Puerto Rico, adopted by the commonwealth of Puerto Rico in 1952, can be traced to 1868, when the first Puerto Rican flag, "The Revolutionary Flag of Lares", was conceived by Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances and embroidered by Mariana "Brazos de Oro" Bracetti. This flag was used in the short-lived Puerto Rican revolt against Spanish rule in the island, known as "El Grito de Lares".[1][2]

Juan de Mata Terreforte, an exiled veteran of "El Grito de Lares" and Vice-President of the Cuban Revolutionary Committee, in New York City, adopted the flag of Lares as the flag of Puerto Rico until 1895, when the current design, modeled after the Cuban flag, was unveiled and adopted by the 59 Puerto Rican exiles of the Cuban Revolutionary committee.[3] The new flag, which consisted of five equal horizontal bands of red (top and bottom) alternating with white; a blue isosceles triangle based on the hoist side bears a large, white, five-pointed star in the center, was first flown in Puerto Rico on March 24, 1897, during the "Intentona de Yauco" revolt. The use and display of the Puerto Rican flag was outlawed and the only flags permitted to be flown in Puerto Rico were the Spanish flag (1492 to 1898) and the flag of the United States (1898 to 1952).

In 1952, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico adopted the same flag design, which was unveiled in 1895 by the Puerto Rican exiles within the Cuban Revolutionary Committee, as its official standard. The color of the triangle that was used by the administration of Luis Muñoz Marín was the dark blue.[4] In 1995, the government of Puerto Rico issued a regulation regarding the use of the Puerto Rican flag titled: "Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico", in which the government specifies the colors to be used but does not specify any official color tones or shades. Therefore, it is not uncommon to see the flag of Puerto Rico with different shades of blue displayed in the island.[5] Several Puerto Rican flags, with darker shades than sky blue were aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery during its flight into outer space on March 15, 2009.[6][7]

History

Spanish era

The introduction of a flag in Puerto Rico can be traced to when Christopher Columbus landed on the island's shore and with the flag appointed to him by the Spanish Crown claimed the island, which he named "San Juan Bautista", in the name of Spain. Columbus wrote in his logbook that on October 12, 1492, he used the Royal Flag, and that his captains used two flags which the Admiral carried in all the ships as ensign, each white with a green cross in the middle and an 'F' and 'Y', both green and crowned with golden, open royal crowns, for Ferdinand II of Aragon and Ysabel (Isabel I).[8] The conquistadores under the command of Juan Ponce de León proceeded to conquer and settle the island. They carried as their military standard the "Spanish Expedition Flag". After the island was conquered and colonized, the flag of Spain was used in Puerto Rico, same as it was used in all of its other colonies.[9]

Once the Spanish armed forces established themselves on the island they began the construction of military fortifications such as La Fortaleza, Fort San Felipe del Morro, Fort San Cristóbal and San Gerónimo. The Spanish Army designed the "Cross of Burgundy Flag" and adopted it as their standard. This flag flew wherever there was a Spanish military installation.[10]

First indigenous design

The independence movement in Puerto Rico gained momentum with the liberation successes of Simón Bolívar and José de San Martín in South America. In 1868, local independence leader Ramón Emeterio Betances urged Mariana Bracetti to knit a revolutionary flag using the flag of the Dominican Republic as an example, promoting the then popular ideal of uniting the three caribbean islands into an Antillean Confederation. The materials for the flag were provided by Eduvigis Beauchamp Sterling, named Treasurer of the revolution by Betances.[11] The flag was divided in the middle by a white Latin cross, the two lower corners were red and the two upper corners were blue with a white star in the upper left blue corner. According to Puerto Rican poet Luis Lloréns Torres the white cross on it stands for the yearning for homeland redemption; the red squares, the blood poured by the heroes of the rebellion and the white star in the blue solitude square, stands for liberty and freedom.[12] The "Revolutionary Flag of Lares" was used in the short-lived rebellion against Spain in what became known as El Grito de Lares (The Cry of Lares).[13] The flag was proclaimed the national flag of the "Republic of Puerto Rico" by Francisco Ramírez Medina, who was sworn in as Puerto Rico's first president, and placed on the high altar of the Catholic Church of Lares, thus becoming the first Puerto Rican Flag.[1] The original Lares flag was taken by a Spanish army officer as a war prize. Many years later it was returned and transferred to the Puerto Rican people. It is now exhibited in the University of Puerto Rico's Museum.[1]

In 1873, following the abdication of Amadeus, Duke of Aosta, as King (1870–1873) and with Spain's change from Kingdom to Republic, the Spanish government issued a new colonial flag for Puerto Rico. The new flag, which was used until 1873, resembled the flag of Spain, with the difference that it had the coat of arms of Puerto Rico in the middle. Spain's flag once more flew over Puerto Rico with the restoration of the Spanish kingdom in 1873, until 1898 the year that the island became a possession of the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1898) in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War.[14]

Current design

(standing L-R) Manuel Besosa, Aurelio Méndez Martínez, and Sotero Figueroa (seated L-R) Juan de M. Terreforte, D. Jose Julio Henna and Roberto H. Todd

Juan de Mata Terreforte, a leader of the Grito de Lares revolt who fought alongside Manuel Rojas, was exiled to New York City. He joined the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee and was named its Vice-President.[3] Terreforte and the members of the Revolutionary committee adopted the Flag of Lares as their standard. In 1892, the Committee was presented with the design of the current flag of Puerto Rico. The new flag's design has been attributed to various Puerto Ricans who were members of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee in New York City.

Some sources document Francisco Gonzalo Marín with presenting a Puerto Rican flag prototype in 1895 for adoption by the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee in New York City. Marín has since been credited by some with the flag's design.[15] There is a letter written by Juan de Mata Terreforte which gives credit to Marin. The original contents of the letter in Spanish are the following:[16]

Which translated in English states the following: The adaptation of the Cuban flag with the colors inverted was suggested by the patriot Francisco Gonzalo Marín in a letter which he wrote from Jamaica. I made the proposition to various Puerto Rican patriots during a meeting at Chimney Hall and it was approved unanimously.[16]

According to other accounts on June 12, 1892, disputed by scholar Armando Martí,[17] Antonio Vélez Alvarado was at his apartment at 219 Twenty-Third Street in Manhattan, when he stared at a Cuban flag for a few minutes, and then took a look at the blank wall in which it was being displayed. Vélez suddenly perceived an optical illusion, in which he perceived the image of the Cuban flag with the colors in the flag's triangle and stripes inverted. Almost immediately he visited a nearby merchant, Domingo Peraza, from whom he bought some crepe paper to build a crude prototype. He later displayed his prototype in a dinner meeting at his neighbor's house, where the owner, Micaela Dalmau vda. de Carreras, had invited José Martí as a guest. Martí was pleasantly impressed by the prototype, and made note of it in a newspaper article published in the Cuban revolutionary newspaper Patria, published on July 2 of that year. Acceptance of the prototype was slow in coming, but grew with time. Francisco Gonzalo Marín, who decided to have a proper flag sewn based on the prototype, presented the new flag's design in New York's "Chimney Corner Hall" a gathering place of independence advocates two years later. The Puerto Rican Flag (with the light blue triangle) soon came to symbolize the ideals of the Puerto Rican independence movement.[18]

In a letter written by Maria Manuela (Mima) Besosa, the daughter of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee member Manuel Besosa, she stated that she sewed the flag. This created a belief that her father could have been its designer. In her letter she described the flag as one which consists of five stripes that alternate from red to white. Three of the stripes are red, and the other two are white. To the left of the flag is a light blue triangle that houses one white five-pointed star. Each part of this flag has its own meaning. The three red stripes represent the blood from the brave warriors. The two white stripes represent the victory and peace that they would have after gaining independence. The white star represented the island of Puerto Rico. The blue represents the sky and blue coastal waters. The triangle represents the three branches of government.[19] Finally, it is also believed by some that it was Lola Rodríguez de Tió who suggested that Puerto Ricans use the Cuban flag with its colors reversed as the model for their own standard.[20] The color of the Cuban flag's blue stripes, however, were a darker shade of blue, according to Professor Martí.

Even though the local newspaper "El Imparcial" on January 17, 1948, that Vélez Alvarado was the "Prócer Que Creó Bandera Patria" (The Father of the Puerto Rican Flag)[21] it may never be known who really designed the current flag, however what is known is that on December 22, 1895, the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee officially adopted the design which represents the current flag. In 1897, Antonio Mattei Lluberas visited the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee in New York City to plan an uprising in Yauco. He returned to Puerto Rico with a Puerto Rican flag[22] and on March 24, 1897, a group of men, led by Fidel Vélez, carried the Puerto Rican flag and attacked the barracks of Spanish Civil Guard of the town Yauco during the revolt against Spanish rule which became known as the "Intentona de Yauco" (Attempted Coup of Yauco). The revolt, which was the second and last major attempt against the Spaniards in the island, was the first time that the flag of Puerto Rico was used on Puerto Rican soil.[23][24]

Outlawing the flag

From December 10, 1898 (the date of the annexation of Puerto Rico by the United States) up until 1952, it was considered a felony to display the Puerto Rican flag in public; the only flag permitted to be flown on the island was the flag of the United States.[25] However, the Puerto Rican flag was often used in the political assemblies of the pro-independence Liberal Party of Puerto Rico and in defiance by the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. In 1932, the Nationalist Party used the flag as its emblem during the elections and in their parades. The Puerto Rico legislature presided by then President of the Puerto Rican Senate Luis Muñoz Marín, passed a bill on May 21, 1948, known as Law 53, making it illegal to display the Puerto Rico Flag, sing a Puerto Rican patriotic song and talk of independence for the islands of Puerto Rico. On June 10, 1948, the United States-appointed Governor of Puerto Rico, Jesús T. Piñero, a member of the ruling Popular Democratic Party (PDP), signed the bill which became known as the "Ley de la Mordaza" (Gag Law).[26] Later that same year Puerto Ricans were permitted to elect a governor and they elected Luis Muñoz Marín. During the Jayuya Uprising of 1950 against United States rule, members of the Nationalist party placed the Puerto Rican flag on top of the town hall; the flag was later taken down by a soldier.

Formal adoption

In 1952, Governor Luis Muñoz Marín and his administration adopted the Puerto Rican flag which was originally designed in 1892, and proclaimed it the official flag of Puerto Rico. The official adaptation of the flag has been interpreted by some as a ploy by Muñoz Marin to neutralize the independence movement in his own party.[27] There were some differences between the original flag of 1892 and the one of 1952 and the meaning of the colors was officially changed. Now the white bars stood for the republican form of government, rather than representing the victory and peace that Puerto Ricans were supposed to have after gaining independence.[28] The sky-blue of the triangle in the original flag was changed to dark blue, resembling that of the flag of the United States, to keep it distanced from its revolutionary roots. For nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos, having the flag represent the government was a desecration,[29] while the independence party accused the government of "corrupting beloved symbols".[27] In 1995, the government of Puerto Rico began to use the sky-blue version once more.[30][31] The government of Puerto Rico issued a regulation in regard to the use of the Puerto Rican flag titled: "Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico; Reglamento Núm. 5282." (Regulations in regard to the use in Puerto Rico of the flag of Commonwealth of Puerto Rico; Regulation No. 5282). In the regulation's "Artículo 2: Definiciones" and "Artículo 2: Descripción y simbolismo" (Article 2: Description and Article 2: Description and symbolism) the government specifies the colors to be used but does not specify any official color tones or shades and as such it is not unusual to see the flag with either tone of blue flown in official settings in Puerto Rico.[5]

Symbol of pride, defiance and protest

Among the many occasions in which the flag has been used as a symbol of pride was when the flag arrived in South Korea during the Korean War. On August 13, 1952, while the men of Puerto Rico's 65th Infantry Regiment (United States) were being attacked by enemy forces on Hill 346, the regiment unfurled the Puerto Rican Flag for the first time in history in a foreign combat zone. During the ceremony Regimental Chaplain Daniel Wilson stated the following:[32][33]

The Commanding Officer Colonel Juan César Cordero Dávila was quoted as saying:[32][33]

On various occasions the flag has been used as a symbol of defiance and protest. In the 1954 attack of the United States House of Representatives in a protest against United States rule of the island, Nationalist leader Lolita Lebrón shouted "¡Viva Puerto Rico Libre!" ("Long live a Free Puerto Rico!") and unfurled the flag of Puerto Rico.[34] On November 5, 2000, Alberto De Jesus Mercado, better known as Tito Kayak, and five other Vieques activists stepped onto the top deck of the Statue of Liberty in New York City, then placed a Puerto Rican flag, with the triangle darker than the light-blue version[35] on the statue's crown, reenacting an earlier protest in the 1970s asking for the release of Puerto Rican prisoners, this time in protest of the United States Navy usage of the island of Vieques as a bombing range.[36]

On March 15, 2009, several Puerto Rican flags were aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery during its flight into outer space. Joseph M. Acaba, the first astronaut of Puerto Rican descent, who is assigned to the crew of STS-119 as a Mission Specialist Educator, carried on his person the flag as a symbol of his Puerto Rican heritage.[6] Acaba presented Governor Luis Fortuño and Secretary of State Kenneth McClintock with two of the flags during his visit in June 2009. The two flags' triangles had a darker blue hue.[37]

The flag is also the subject of the song "Que Bonita Bandera" (What a beautiful flag) written in 1968 and made popular by Puerto Rican folksinger Florencio "Ramito" Morales Ramos. Astronaut Acaba, requested that the crew be awakened on March 19, 2009 (Day 5), with the Puerto Rico folklore song, sung by Jose Gonzalez and Banda Criolla, during their space flight.[38]

Diplomatic contact regarding similar flags

In the 1950s Puerto Rico contacted Norway's Foreign Ministry in an attempt to have Norwegian shipping company Norled stop using a flag that has a significant[39] likeness to Puerto Rico's flag. (Norway has not legally challenged the shipping company's position, that their flag is older than Puerto Rico's.[39] The shipping company's flag is still in use, as of 2016.[39])

Gallery

Flag of Province of Puerto Rico (1873–1898)

Flag of Province of Puerto Rico (1873–1898).svg.png) Lares revolutionary flag of 1868

Lares revolutionary flag of 1868 Spanish–American War flag: flag of the Batallón Provisional No. 3 de Puerto Rico (3rd Provisional Battalion of Puerto Rico).

Spanish–American War flag: flag of the Batallón Provisional No. 3 de Puerto Rico (3rd Provisional Battalion of Puerto Rico). Flag of Spain (1873–1874) First Spanish Republic.

Flag of Spain (1873–1874) First Spanish Republic..png) Original Puerto Rican flag design of 1895

Original Puerto Rican flag design of 1895 Puerto Rican flag aboard the Discovery Space Shuttle (March 15, 2009)

Puerto Rican flag aboard the Discovery Space Shuttle (March 15, 2009)

See also

- List of Puerto Rican flags

- List of municipal flags of Puerto Rico

- Coat of arms of Puerto Rico

- Seal of Puerto Rico

- Flag of Cuba, a similar flag with the red and blue reversed, and longer length

- Det Stavangerske Dampskibsselskap - A Norwegian shipping company with a virtually identical flag in its logo

References

- Footnotes

- 1 2 3 "Puerto Rico". flagspot.net. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Puerto Rico - Cinco Siglos de Historia"; by: Francisco Sacrano; publisher: McGraw Hill Interamericana, SA, 1993; pag. 533

- 1 2 "Enciclopedia de Puerto Rico". enciclopediapr.org. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Flags of the World; Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Flags of the World, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- 1 2 Reglamento sobre el Uso en Puerto Rico de la Bandera del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico(Spanish), Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Retrieved on Feb. 25, 2009 (in Spanish)

- 1 2 "Boricua a Punto de Abordar El Discovery, Acaba llevara bandera de PR" - El Nuevo Dia; By Marcia Dunn Associated Press, Retrieved March 12, 2009 (Spanish)

- ↑ "The Flag of Puerto Rico | District of Puerto Rico". Retrieved 2015-06-11.

- ↑ Enchanted Learning, Zoom Explorers, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ Christopher Columbus' Flags 1492, Flags of the World, Retrieved February 25, 2009

- ↑ Spanish Burgundy Flag, University of Georgia, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ Julia Sosa. "Familia: Brief History on the Beauchamp Origens". ancestry.com. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ "Lares--municipio de Puerto Rico-datos y fotos-videos". prfrogui.com. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Peres Moris, José, Historia de la Insurrección de Lares, 1871 (in Spanish), Library of Congress, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ Popular Expression and National Identity in Puerto Rico: The Struggle for Self, Community, and Nation; by Lillian Guerra; Pg. 200; Publisher: University Press of Florida; 1st edition (June 30, 1998); ISBN 0-8130-1594-4; ISBN 978-0-8130-1594-1

- ↑ "Latin America's Wars Volume I: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791-1899"; by Robert L. Scheina; Pg. 359; Publisher: Potomac Books Inc.; 1 edition (January 2003); ISBN 1-57488-449-2; ISBN 978-1-57488-449-4

- 1 2 "Vida, pasión y muerte de Francisco Gonzalo Marín [Pachín]". nireblog.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ https://editorialakelarre.blogspot.com/2016/11/sobre-las-banderas-de-cuba-y-puerto-rico.html?showComment=1480645578550#c669442883047578527

- ↑ Antonio Vélez Alvarado, amigo y colaborador consecuente de Martí y Betances, Author: Dávila, Ovidio; pp. 11-13.; Publisher: San Juan, P.R. : Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (Institute of Puerto Rican Culture), 2002. (in Spanish)

- ↑ Puerto Rico, Welcome to Puerto Rico, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ Lola Rodríguez de Tió, Library of Congress, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ "Muere Antonio Vélez Alvarado, Prócer Que Creó Bandera Patria", El Imparcial, January 17, 1948, pág. "B"

- ↑ "Historia militar de Puerto Rico"; by Hector Andres Negroni (Author); Pages: 307; Publisher: Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario (1992); Language: Spanish; ISBN 84-7844-138-7; ISBN 978-84-7844-138-9

- ↑ Sabia Usted? (in Spanish), Sabana Grande, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ The Flag, Flags of the World, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ Photos of the Jayuya Uprising, Latin American Studies, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ "History of Puerto Rico - 1900 - 1949". topuertorico.org. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Puerto Rico: Culture, Politics, and Identity"; by Nancy Morris, Published by Praeger/Greenwood 1995; ISBN 0-275-95452-8. P.51

- ↑ Flag of Puerto Rico by Martín Espada an authority and professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Martín Espada, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ "Luis Muñoz Marín: Puerto Rico's Democratic Revolution" Published by Editorial UPR, 2006; ISBN 0-8477-0158-1. P.90

- ↑ Flag of Puerto Rico, Flags of the World, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- ↑ Welcome to Puerto Rico - Flag of Puerto Rico, Welcome to Puerto Rico, Retrieved Feb. 25, 2009

- 1 2 "Letter Col. Juan C. Cordero to Brig. Gen. Robert M. Bathurst, September 5, 1952." A transcription of said document is currently available at www.valerosos.com.

- 1 2 "Saviors of the Cause The Role of the Puerto Rican Soldier in One Man’s Crusade"; by Luis Asencio Camacho

- ↑ Associated Press (2004-02-29). "No one expected attack on Congress in 1954". Holland Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2005-03-22. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ http://tlloh.com/puerto-rican-flag-on-the-statue-of-liberty/

- ↑ Vieques: A Photographically Illustrated Guide to the Island, Its History and Its Culture; by Gerald Singer; page 183; Publisher: Sombrero Publishing Company; ISBN 0-9641220-4-9; ISBN 978-0-9641220-4-8

- ↑ http://www.elnuevodia.com/visitaralaislajosephacaba-574513.html

- ↑ El Nuevo Dia Archived January 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine., (Spanish newspaper) Retrieved March 21, 2009

- 1 2 3 "Dette flagget skapte diplomatiske bruduljar". Bergens Tidende. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Primary sources

- Act No.1, Approved July 24, 1952.

- Regulations on the Use of the Puerto Rico flag. Núm. 5282, August 3, 1995 (in Spanish)

- Mapas, Escudos y Banderas de Puerto Rico (Actualized ed.). Puerto Rico: Láminas Latino. 2007. (in Spanish)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flags of Puerto Rico. |

- Puerto Rico at Flags of the World

- Puerto Rico flags at Vexilla mundi

- The Flag of The Jatibonicu Taíno Tribal Nation

- Academic Study on blue triangle in Puerto Rico flag

.svg.png)