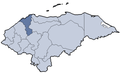

Puerto Cortés

| Puerto Cortés Puerto Caballos | ||

|---|---|---|

| town | ||

|

The bridge into Puerto Cortés | ||

| ||

| Nickname(s): "El Puerto" | ||

Puerto Cortés | ||

| Coordinates: 15°51′N 87°56′W / 15.850°N 87.933°W | ||

| Country |

| |

| Department | Cortés | |

| Founded | 1524 | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 391 km2 (151 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015) | ||

| • Total | 126,009 | |

| • Density | 320/km2 (830/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | América Central (UTC-6) | |

Puerto Cortės, originally known as Puerto de Caballos,[1] is a city on the north Caribbean coast of Honduras, right on the Laguna de Alvarado, north of San Pedro Sula and east of Omoa, with a natural bay. The present city was founded in the early colonial period. It grew rapidly in the twentieth century, thanks to the then railroad, and banana production. In terms of volume of traffic the seaport is the largest in Central America and the 36th largest in the world.[2] As of 2014, Puerto Cortés has a population of some 200,000.

History

Gil González Dávila founded the city in 1524 and called Villa de la Natividad de Nuestra Señora, now known as Cieneguita. In 1526 Hernán Cortés came to punish González Dávila and when he arrived on Honduras' coast from Mexico and started unloading horses and cargo from the ships, several horses were drowned, and for that reason Cortés called it Puerto Caballos. By 1533, a local native leader, called Çiçumba (or Çoçumba, or Socremba, or Joamba ... we don't really know since the Spanish recorded so many variants of his name) had destroyed the town, reportedly taking a woman from Sevilla, Spain captive. After Çiçumba's defeat in 1536 by Pedro de Alvarado, a new town, Puerto de Caballos was founded on the southern shore of the body of water known as the Laguna de Alvarado.

The English attacked Puerto Caballos as they did other places along the Honduran coast.Christopher Newport briefly occupied the town in the Battle of Puerto Caballos, part of the Anglo–Spanish War.[3] Because it was vulnerable to pirates until the building of the Spanish fort at Omoa in the 18th century, it had few permanent residents in the 16th and 17th centuries. People preferred to come out to the coast from San Pedro when a ship came into port. In 1869 Puerto Caballos changed its name to Puerto Cortés in honour of Hernán Cortés.

Bananas, railroads and development in the twentieth century

The proposal to construct an "inter-oceanic railway" (Ferrocarril Interoceánico) in 1850, a product of the demand for transport from the Atlantic to the Pacific caused by the United States Gold Rush of 1849, began with the anchoring of the railroad at Puerto Cortés. The rail line construction had many problems.[4] In 1876 President Marco Aurelio Soto nationalised the Trans-Oceanic Railroad, which only reached to San Pedro Sula. When the Panama Canal was completed in 1903, the alternative plan to connect the coasts was abandoned. The region became an early centre for banana production in Honduras through cultivation and export, and the port was a leader in the export of bananas.

The early banana export industry came to be dominated by foreigners; among the first foreigners to obtain a government concession was William Frederick Streich of Philadelphia in 1902. His concession was in the vicinity of Omoa and both banks of the Cuyamel River. However, in 1910 Samuel Zemurray's Cuyamel Fruit Company purchased these 5,000 acres, but soon branched out, both with more land and with political and tax concessions, especially after Zemurray installed Manuel Bonilla in office as president using mercenaries hired in the area and abroad. In addition to awarding Cuyamel additional land, Bonilla also waived the company's tax obligations. Cuyamel had built port facilities at Omoa, but also began using the facilities at Puerto Cortés and soon came to dominate them to the point that local shippers had to ask Cuyamel's permission to use the port.[5] In 1918, Cuyamel constructed a railroad spur into Puerto Cortés, and in 1920 he obtained effective control over the National Railroad, and from this and a network of clandestine railroads the company effectively controlled all transport to the port.[6] When Zemurray sold Cuyamel Fruit to United Fruit in 1929, the giant company had great influence in Puerto Cortés and in Honduras as a whole.

The city

In August, Puerto Cortés celebrates its local or patronal festivities during two weeks. The last day (a Saturday) is known as Noche Veneciana (Venice's night). 15 August is a local holiday in honour of Virgen de la Asunción (Puerto Cortés local patroness or saint).

In September 2001, the Bridge Laguna de Alvarado (Alvarado lagoon) was rebuilt and inaugurated after the old bridge, a 50 years old structure, was badly damaged in 1998 by Hurricane Mitch. A concrete wall that surrounds and protects a portion of the coastline in the bay area, was built close to the north end of Bridge La Laguna, this wall is known as El Malecón, the Spanish word for 'jetty' or 'pier'.

The first four-lane highway in Honduras was inaugurated in 1996, connecting Puerto Cortés and the city of San Pedro Sula.

Seaport

In 1966, the Empresa Nacional Portuaria (Honduras National Port Authority)[7] was created. A free trade zone was created in 1976.

Among all worldwide seaports that export containers with goods with destination to USA, Puerto Cortés is the 36th in terms of volume.

Because of its proximity to US seaports in the Gulf of Mexico and on the East Coast and its seaport infrastructure, Puerto Cortés was included in the US Container Security Initiative (CSI), the first such port in Central America. In December 2005, the US government signed an agreement with Honduras's government and opened a US Customs Office in Puerto Cortés.[8] Under this agreement, all containers exported from Puerto Cortés that are destined for any US seaport are checked by US Customs officials in Honduras.

In March 2007, under the Megaport initiative, three RPMs (Radiation Portal Monitors) were already installed in Puerto Cortés by US DOE to inspect all containers with destination to USA, checking for possible dangerous radioactive threats. On 2 April 2007 the RPMs became operative.[9]

Sports

Puerto Cortés is home of a football team known as Platense, which in 1966 won its first Honduran National Football Champion. In 2001 the team won its second national championship. They play their home games at the Estadio Excélsior. Atlético Portuario was briefly another football club based in the city.

Notable people and natives

- Ibis Fernandez – Author,[10][11] Animator,[12] Actor, Producer and Filmmaker.[13]

- Edgar Alvarez – Football player.

- Roger Espinoza – Football player

- Julio César de León – Football player.

- Vilma Cecilia Morales – Former President of Honduras Supreme Court of Justicet.

- Zora Neale Hurston – African American writer, scholar and political activist resided at the Hotel Cosenza from May 1947 to February 1948 while writing her book Seraph on the Suwanee.[14]

- Axel Garrido Rosenvinge – Danish politician born in Puerto Cortes. Businessman and ex football player of the U-19 Danish League.[15][16][17]

Elected mayors

In 1982, a new constitution was approved; before that year mayors were designated "by finger" by Tegucigalpa top government officials.

- 1982–1983: Roy Reyes Orellana (Partido Liberal)

- 1984–1985: Mario Sabillón (Partido Liberal)

- 1986–1990: Romulo Montoya (Partido Liberal)

- 1990–1991: Rolando Méndez (Partido Nacional).

- 1992: Rolando Orellana Cruz (Partido Nacional).

- 1992–1993: Alvaro Zacarías Mena (Partido Nacional).

- 1994–1997: Marlon Guillermo Lara Orellana(Partido Liberal)

- 1998–2001: Marlon Guillermo Lara Orellana (Partido Liberal) (re-elected)

- 2002–2005: Marlon Guillermo Lara Orellana (Partido Liberal) (re-elected)

- 2006–2009: Alan Ramos (Partido Liberal)

- 2010–2014: Allan Ramos (Partido Liberal) (re-elected)

- 2014–2018: Allan Ramos (Partido Liberal) (re-elected)

Schools

- There is an elementary school named República de Mexico.

- There is an elementary school named República de Chile.

- There is an elementary school named Saint Martin de Porres in honour of this Saint from Peru.

- There is a private Catholic high school named Sacred Heart of Jesus (Sagrado Corazón de Jesús).

- There is a high school academy named Saint John Bosco (San Juan Bosco) in honour of that saint.

- There is a bilingual school (elementary school, junior high and high school) named Saint John the Baptist in honour of this Prophet.

- There is a high school named after former US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Facts

- There is a beach known as La Coca-Cola, named after the soft drink company due to La Embotelladora La Coca-Cola being situated on this beach. The plant once employed many workers whose meals depended on this job.

- In the decade of the 1930s a small whale was captured in the bay of Puerto Cortés. This was a very rare situation, since whales are not normally found in the Caribbean Sea.

- The USS Hornet aircraft carrier made Puerto Cortés a port of call in 1963.

- There is football stadium known as Estadio Excelsior (the home of Club Deportivo Platense). In 1965 an Argentine professional football club Chacarita Juniors (then in Argentine first division) played here, defeating Platense(2–1).

- Since 1986, the Municipality of Puerto Cortés receives four percent (4%) of all revenues (income) received by the Honduras Custom office in Puerto Cortés, and four percent (4%) of all revenues received by La Empresa Nacional Portuaria (Honduras Port Authority) in the Seaport. This fee is known as El Cuatro por Ciento (The Four Percent). The same percentage (4%) is also received by two other municipalities where Empresa Nacional Portuaria operates (Castilla and San Lorenzo). This percentage is applied to all revenues received by the Honduras Custom Office in these places.

Medical services

- Puerto Cortés offers a variety of medical health care services.

Public hospitals

- Centro Medico Litoral Atlántico

- CEMECO

- CEDEM

- Centro Medico Handal

- Hospital IHSS (Public)

- Hospital del Area (Public)

Rehabilitation Center

References

- ↑ Historia de Puerto Cortés

- ↑ Mega Puerto

- ↑ David Marley, Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of armed conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the present (ABC Clio, 2008) 1: 126.

- ↑ Relación histórica de los contratiempos que ha sufrido la construcción de un ferrocarril á través de la República de Honduras (London: Clayton and Temple, 1875)

- ↑ Glen Chambers, Race, Nation and West Indian Immigration to Honduras, 1890–1940 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010) pp. 28–30. Chambers cites Honduran historian Manuel Argueto, Bananas y politica: Samuel Zemurray y la Cuyamel Fruit Company en Honduras (Tegulcigalpa, 1989)

- ↑ Vilma Laínez and Víctor Meza, "El enclave en la historia de Honduras", Anuario de Estudos Centroamericanos 1 (1974)

- ↑ Portuaria

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Macromedia Flash Animation and Cartooning: A Creative Guide. McGraw-Hill Companies. 19 December 2001. ISBN 9780072133233.

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Ibis Fernandez: Books, Biography, Blog, Audiobooks, Kindle". www.amazon.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Cinestar Interactive |". cinestarint.com. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Ibis Fernandez". IMDb. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Her letters from Puerto Cortes are reproduced in Carla Kaplan, ed Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters (New York: Random House, 2003) pp. 550–68.

- ↑ "Han har lagt Honduras bag sig". www.jv.dk. 14 September 2013. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "Unge projekter Der blev arbejdet kreativt på højskolen østersøen". www.jv.dk. 8 April 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

- ↑ "Unge udvikler fremtidens studieby". TV SYD. Retrieved 2016-05-08.

Coordinates: 15°53′N 87°57′W / 15.883°N 87.950°W

.svg.png)