Corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonest or unethical conduct by a person entrusted with a position of authority, often to acquire personal benefit.[1] Corruption may include many activities including bribery and embezzlement, though it may also involve practices that are legal in many countries.[2] Government, or 'political', corruption occurs when an office-holder or other governmental employee acts in an official capacity for personal gain.

Scales of corruption

Stephen D. Morris,[3] a professor of politics, writes that political corruption is the illegitimate use of public power to benefit a private interest. Economist Ian Senior[4] defines corruption as an action to (a) secretly provide (b) a good or a service to a third party (c) so that he or she can influence certain actions which (d) benefit the corrupt, a third party, or both (e) in which the corrupt agent has authority. Daniel Kaufmann,[5] from the World Bank, extends the concept to include 'legal corruption' in which power is abused within the confines of the law—as those with power often have the ability to make laws for their protection. The effect of corruption in infrastructure is to increase costs and construction time, lower the quality and decrease the benefit.[6]

Corruption can occur on different scales. Corruption ranges from small favors between a small number of people (petty corruption),[7] to corruption that affects the government on a large scale (grand corruption), and corruption that is so prevalent that it is part of the everyday structure of society, including corruption as one of the symptoms of organized crime.

Petty corruption

Petty corruption occurs at a smaller scale and takes place at the implementation end of public services when public officials meet the public. For example, in many small places such as registration offices, police stations and many other private and government sectors.

Grand corruption

Grand corruption is defined as corruption occurring at the highest levels of government in a way that requires significant subversion of the political, legal and economic systems. Such corruption is commonly found in countries with authoritarian or dictatorial governments but also in those without adequate policing of corruption.[8]

The government system in many countries is divided into the legislative, executive and judiciary branches in an attempt to provide independent services that are less subject to grand corruption due to their independence from one another.[9]

Systemic corruption

Systemic corruption (or endemic corruption)[10] is corruption which is primarily due to the weaknesses of an organization or process. It can be contrasted with individual officials or agents who act corruptly within the system.

Factors which encourage systemic corruption include conflicting incentives, discretionary powers; monopolistic powers; lack of transparency; low pay; and a culture of impunity.[11] Specific acts of corruption include "bribery, extortion, and embezzlement" in a system where "corruption becomes the rule rather than the exception."[12] Scholars distinguish between centralized and decentralized systemic corruption, depending on which level of state or government corruption takes place; in countries such as the Post-Soviet states both types occur.[13] Some scholars argue that there is a negative duty of western governments to protect against systematic corruption of underdeveloped governments.[14][15]

Corruption in different sectors

Corruption can occur in any sectors, whether they be public or private industry or even NGOs. However, only in democratically controlled institutions is there an interest of the public (owner) to develop internal mechanisms to fight active or passive corruption, whereas in private industry as well as in NGOs there is no public control. Therefore, the owners' investors' or sponsors' profits are largely decisive.

Government/public sector

Public sector corruption includes corruption of the political process and of government agencies such as the police as well as corruption in processes of allocating public funds for contracts, grants, and hiring. Recent research by the World Bank suggests that who makes policy decisions (elected officials or bureaucrats) can be critical in determining the level of corruption because of the incentives different policy-makers face.[16]

Political corruption

Political corruption is the abuse of public power, office, or resources by elected government officials for personal gain, by extortion, soliciting or offering bribes. It can also take the form of office holders maintaining themselves in office by purchasing votes by enacting laws which use taxpayers' money.[17] Evidence suggests that corruption can have political consequences- with citizens being asked for bribes becoming less likely to identify with their country or region.[18]

Police corruption

Police corruption is a specific form of police misconduct designed to obtain financial benefits, other personal gain, career advancement for a police officer or officers in exchange for not pursuing, or selectively pursuing, an investigation or arrest and/or aspects of the thin blue line itself, where force members collude in lies to protect other members from accountability. One common form of police corruption is soliciting and/or accepting bribes in exchange for not reporting organized drug or prostitution rings or other illegal activities.

Another example is police officers flouting the police code of conduct in order to secure convictions of suspects—for example, through the use of falsified evidence. More rarely, police officers may deliberately and systematically participate in organized crime themselves. In most major cities, there are internal affairs sections to investigate suspected police corruption or misconduct. Similar entities include the British Independent Police Complaints Commission.

Judicial corruption

Judicial corruption refers to corruption related misconduct of judges, through receiving or giving bribes, improper sentencing of convicted criminals, bias in the hearing and judgement of arguments and other such misconduct.

Governmental corruption of judiciary is broadly known in many transitional and developing countries because the budget is almost completely controlled by the executive. The latter undermines the separation of powers, as it creates a critical financial dependence of the judiciary. The proper national wealth distribution including the government spending on the judiciary is subject of the constitutional economics.

It is important to distinguish between the two methods of corruption of the judiciary: the government (through budget planning and various privileges), and the private.[19] Judicial corruption can be difficult to completely eradicate, even in developed countries.[20] Corruption in judiciary also involve the government in power using judicial arm of government to oppress the opposition parties in the detriments of the state.

Corruption in the educational system

Corruption in education is a worldwide phenomenon. Corruption in admissions to universities is traditionally considered as one of the most corrupt areas of the education sector.[21] Recent attempts in some countries, such as Russia and Ukraine, to curb corruption in admissions through the abolition of university entrance examinations and introduction of standardized computer graded tests have largely failed.[22] Vouchers for university entrants have never materialized.[23] The cost of corruption is in that it impedes sustainable economic growth.[23][23] Endemic corruption in educational institutions leads to the formation of sustainable corrupt hierarchies.[24][25][26] While higher education in Russia is distinct with widespread bribery, corruption in the US and the UK features a significant amount of fraud.[27][28] The US is distinct with grey areas and institutional corruption in the higher education sector.[29][30] Authoritarian regimes, including those in the former Soviet republics, encourage educational corruption and control universities, especially during the election campaigns.[31] This is typical for Russia,[32] Ukraine,[33] and Central Asian regimes,[34] among others. The general public is well aware of the high level of corruption in colleges and universities, including thanks to the media.[35][36] Doctoral education is no exception, with dissertations and doctoral degrees available for sale, including for politicians.[37] Russian Parliament is notorious for "highly educated" MPs [38] High levels of corruption are a result of universities not being able to break away from their Stalinist past, over bureaucratization,[39] and a clear lack of university autonomy.[40] Both quantitative and qualitative methodologies are employed to study education corruption,[41] but the topic remains largely unattended by the scholars. In many societies and international organizations, education corruption remains a taboo. In some countries, such as certain eastern European countries and certain Asian countries, corruption occurs frequently in universities.[42] This can include bribes to bypass bureaucratic procedures and bribing faculty for a grade.[42][43] The willingness to engage in corruption such as accepting bribe money in exchange for grades decreases if individuals perceive such behavior as very objectionable, i.e. a violation of social norms and if they fear sanctions in terms of the severity and probability of sanctions.[43]

Within labor unions

The Teamsters (International Brotherhood of Teamsters) is an example of how the civil RICO process can be used. For decades, the Teamsters have been substantially controlled by La Cosa Nostra. Since 1957, four of eight Teamster presidents were indicted, yet the union continued to be controlled by organized crime elements. The federal government has been successful at removing the criminal influence from this 1.4 million-member union by using the civil process.[44]

Corruption in religion

The history of religion includes numerous examples of religious leaders calling attention to corruption in the religious practices and institutions of their time. Jewish prophets Isaiah and Amos berate the rabbinical establishment of Ancient Judea for failing to live up to the ideals of the Torah.[45] In the New Testament, Jesus accuses the rabbinical establishment of his time of hypocritically following only the ceremonial parts of the Torah and neglecting the more important elements of justice, mercy and faithfulness.[46] In 1517, Martin Luther accuses the Catholic Church of widespread corruption, including selling of indulgences.[47]

In 2015, Princeton University professor Kevin M. Kruse advances the thesis that business leaders in the 1930s and 1940s collaborated with clergymen, including James W. Fifield Jr., to develop and promote a new hermeneutical approach to Scripture that would de-emphasize the social Gospel and emphasize themes, such as individual salvation, more congenial to free enterprise.[48]

- Business leaders, of course, had long been working to "merchandise" themselves through the appropriation of religion. In organizations such as Spiritual Mobilization, the prayer breakfast groups, and the Freedoms Foundation, they had linked capitalism and Christianity and, at the same time, likened the welfare state to godless paganism.[49]

Corruption in philosophy

19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer acknowledges that academics, including philosophers, are subject to the same sources of corruption as the society they inhabit. He distinguishes the corrupt "university" philosophers, whose "real concern is to earn with credit an honest livelihood for themselves and ... to enjoy a certain prestige in the eyes of the public" [50] from the genuine philosopher, whose sole motive is to discover and bear witness to the truth.

- To be a philosopher, that is to say, a lover of wisdom (for wisdom is nothing but truth), it is not enough for a man to love truth, in so far as it is compatible with his own interest, with the will of his superiors, with the dogmas of the church, or with the prejudices and tastes of his contemporaries; so long as he rests content with this position, he is only a φίλαυτος [lover of self], not a φιλόσοφος [lover of wisdom]. For this title of honor is well and wisely conceived precisely by its stating that one should love the truth earnestly and with one’s whole heart, and thus unconditionally and unreservedly, above all else, and, if need be, in defiance of all else. Now the reason for this is the one previously stated that the intellect has become free, and in this state it does not even know or understand any other interest than that of truth.[51]

Methods

In systemic corruption and grand corruption, multiple methods of corruption are used concurrently with similar aims.[52]

Bribery

Bribery involves the improper use of gifts and favours in exchange for personal gain. This is also known as kickbacks or, in the Middle East, as baksheesh. It is the most common form of corruption. The types of favours given are diverse and may include money, gifts, sexual favours, company shares, entertainment, employment and political benefits. The personal gain that is given can be anything from actively giving preferential treatment to having an indiscretion or crime overlooked.[53]

Bribery can sometimes form a part of the systemic use of corruption for other ends, for example to perpetrate further corruption. Bribery can make officials more susceptible to blackmail or to extortion.

Embezzlement, theft and fraud

Embezzlement and theft involve someone with access to funds or assets illegally taking control of them. Fraud involves using deception to convince the owner of funds or assets to give them up to an unauthorized party.

Examples include the misdirection of company funds into "shadow companies" (and then into the pockets of corrupt employees), the skimming of foreign aid money, scams and other corrupt activity.

Extortion and blackmail

While bribery is the use of positive inducements for corrupt aims, extortion and blackmail centre around the use of threats. This can be the threat of violence or false imprisonment as well as exposure of an individual's secrets or prior crimes.

This includes such behavior as an influential person threatening to go to the media if they do not receive speedy medical treatment (at the expense of other patients), threatening a public official with exposure of their secrets if they do not vote in a particular manner, or demanding money in exchange for continued secrecy.

Networking

Networking can be an effective way for job-seekers to gain a competitive edge over others in the job-market. The idea is to cultivate personal relationships with prospective employers, selection panelists, and others, in the hope that these personal affections will influence future hiring decisions. This form of networking has been described as an attempt to corrupt formal hiring processes, where all candidates are given an equal opportunity to demonstrate their merits to selectors. The networker is accused of seeking non-meritocratic advantage over other candidates; advantage that is based on personal fondness rather than on any objective appraisal of which candidate is most qualified for the position.[54][55]

Types of corrupt gains

Abuse of discretion

Abuse of discretion refers to the misuse of one's powers and decision-making facilities. Examples include a judge improperly dismissing a criminal case or a customs official using their discretion to allow a banned substance through a port.

Favoritism, nepotism and clientelism

Favouritism, nepotism and clientelism involve the favouring of not the perpetrator of corruption but someone related to them, such as a friend, family member or member of an association. Examples would include hiring or promoting a family member or staff member to a role they are not qualified for, who belongs to the same political party as you, regardless of merit.[56]

Some states do not forbid these forms of corruption.

Corruption and economic growth

Corruption is strongly negatively associated with the share of private investment and, hence, it lowers the rate of economic growth.[57]

Corruption reduces the returns of productive activities. If the returns to production fall faster than the returns to corruption and rent-seeking activities, resources will flow from productive activities to corruption activities over time. This will result in a lower stock of producible inputs like human capital in corrupted countries.[57]

Corruption creates the opportunity for increased inequality, reduces the return of productive activities, and, hence, makes rentseeking and corruption activities more attractive. This opportunity for increased inequality not only generates psychological frustration to the underprivileged but also reduces productivity growth, investment, and job opportunities.[57]

Causes of corruption

According to a 2017 survey study, the following factors have been attributed as causes of corruption:[58]

- Higher levels of market and political monopolization

- Low levels of democracy, weak civil participation and low political transparency

- Higher levels of bureaucracy and inefficient administrative structures

- Low press freedom

- Low economic freedom

- Large ethnic divisions and high levels of in-group favoritism

- Gender inequality

- Low degree of integration in the world economy

- Large government size

- Low levels of government decentralization

- Former French, Portuguese, or Spanish colonies have been shown to have greater corruption than former British colonies

- Resource wealth

- Poverty

- Political instability

- Weak property rights

- Contagion from corrupt neighboring countries

- Low levels of education

- Low Internet access

Preventing corruption

R. Klitgaard[59] postulates that corruption will occur if the corrupt gain is greater than the penalty multiplied by the likelihood of being caught and prosecuted:

Corrupt gain > Penalty × Likelihood of being caught and prosecuted

The degree of corruption will then be a function of the degree of monopoly and discretion in deciding who should get how much on the one hand and the degree to which this activity is accountable and transparent on the other hand. Still, these equations (which should be understood in a qualitative rather than a quantitative manner) seem to be lacking one aspect: a high degree of monopoly and discretion accompanied by a low degree of transparency does not automatically lead to corruption without any moral weakness or insufficient integrity. Also, low penalties in combination with a low probability of being caught will only lead to corruption if people tend to neglect ethics and moral commitment. The original Klitgaard equation has therefore been amended by C. Stephan[60] into:

Degree of corruption = Monopoly + Discretion – Transparency – Morality

According to Stephan, the moral dimension has an intrinsic and an extrinsic component. The intrinsic component refers to a mentality problem, the extrinsic component to external circumstances like poverty, inadequate remuneration, inappropriate work conditions and inoperable or overcomplicated procedures which demoralize people and let them search for "alternative" solutions.

According to the amended Klitgaard equation, limitation of monopoly and regulator discretion of individuals and a high degree of transparency through independent oversight by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the media plus public access to reliable information could reduce the problem. Djankov and other researchers[61] have independently addressed the important role information plays in fighting corruption with evidence from both developing and developed countries. Disclosing financial information of government officials to the public is associated with improving institutional accountability and eliminating misbehavior such as vote buying. The effect is specifically remarkable when the disclosures concern politicians’ income sources, liabilities and asset level instead of just income level. Any extrinsic aspects that might reduce morality should be eliminated. Additionally, a country should establish a culture of ethical conduct in society with the government setting the good example in order to enhance the intrinsic morality.

Anti-corruption programmes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-corruption. |

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA, USA 1977) was an early paradigmatic law for many western countries i.e. industrial countries of the OECD. There, for the first time the old principal-agent approach was moved back where mainly the victim (a society, private or public) and a passive corrupt member (an individual) were considered, whereas the active corrupt part was not in the focus of legal prosecution. Unprecedented, the law of an industrial country directly condemned active corruption, particularly in international business transactions, which was at that time in contradiction to anti-bribery activities of the World Bank and its spin-off organization Transparency International.

As early as 1989 the OECD had established an ad hoc Working Group in order to explore "...the concepts fundamental to the offense of corruption, and the exercise of national jurisdiction over offenses committed wholly or partially abroad."[62] Based on the FCPA concept, the Working Group presented in 1994 the then "OECD Anti-Bribery Recommendation" as precursor for the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions[63] which was signed in 1997 by all member countries and came finally into force in 1999. However, because of ongoing concealed corruption in international transactions several instruments of Country Monitoring[64] have been developed since then by the OECD in order to foster and evaluate related national activities in combating foreign corrupt practices.

In 2013, a document[65] produced by the economic and private sector professional evidence and applied knowledge services help-desk discusses some of the existing practices on anti-corruption. They found:

- The theories behind the fight against corruption are moving from a Principal agent approach to a collective action problem. Principal-agent theories seem not to be suitable to target systemic corruption.

- The role of multilateral institutions has been crucial in the fight against corruption. UNCAC provides a common guideline for countries around the world. Both Transparency International and the World Bank provide assistance to national governments in term of diagnostic and design of anti-corruption policies.

- The use of anti-corruption agencies have proliferated in recent years after the signing of UNCAC. They found no convincing evidence on the extent of their contribution, or the best way to structure them.

- Traditionally anti-corruption policies have been based on success experiences and common sense. In recent years there has been an effort to provide a more systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of anti-corruption policies. They found that this literature is still in its infancy.

- Anti-corruption policies that may be in general recommended to developing countries may not be suitable for post-conflict countries. Anti-corruption policies in fragile states have to be carefully tailored.

- Anti-corruption policies can improve the business environment. There is evidence that lower corruption may facilitate doing business and improve firm’s productivity. Rwanda in the last decade has made tremendous progress in improving governance and the business environment providing a model to follow for post-conflict countries.[65]

Corruption tourism

In some countries people travel to corruption hot spots or a specialist tour company takes them on corruption city tours, as it is the case in Prague.[66][67][68][69] Corruption tours have also occurred in Chicago,[70] and Mexico City [71][72]

Legal corruption

Though corruption is often viewed as illegal, there is an evolving concept of legal corruption,[5][73] as developed by Daniel Kaufmann and Pedro Vicente. It might be termed as processes which are corrupt, but are protected by a legal (that is, specifically permitted, or at least not proscribed by law) framework.[74]

Examples of legal corruption

In 1977 the USA had enacted the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA)[75] "for the purpose of making it unlawful... to make payments to foreign government officials to assist in obtaining or retaining business" and invited all OECD countries to follow suit. In 1997 a corresponding OECD Anti-Bribery Convention was signed by its members.[76][77]

17 years after the FCPA enacting, a Parliamentary Financial Commission in Bonn presented a comparative study on legal corruption in industrialized OECD countries[78] As a result, they reported that in most industrial countries even at that time (1994) foreign corruption was legal, and that their foreign corrupt practices had been diverging to a large extent, ranging from simple legalization, through governmental subsidization (tax deduction), up to extremes like in Germany where foreign corruption was fostered,[79] whereas domestic was legally prosecuted. Consequently, in order to support national export corporations the Parliamentary Financial Commission recommended to reject a related previous Parliamentary Proposal by the opposition leader which had been aiming to limit German foreign corruption on the basis of the US FCPA.[80] Only after the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention came into force Germany withdraw the legalization of foreign corruption in 1999.[81]

Foreign corrupt practices of industrialized OECD countries 1994 (Parliamentary Financial Commission study, Bonn)[78]

Belgium: bribe payments are generally tax deductible as business expenses if the name and address of the beneficiary is disclosed. Under the following conditions kickbacks in connection with exports abroad are permitted for deduction even without proof of the receiver:

- Payments must be necessary in order to be able to survive against foreign competition

- They must be common in the industry

- A corresponding application must be made to the Treasury each year

- Payments must be appropriate

- The payer has to pay a lump-sum to the tax office to be fixed by the Finance Minister (at least 20% of the amount paid).

In the absence of the required conditions, for corporate taxable companies paying bribes without proof of the receiver, a special tax of 200% is charged. This special tax may, however, be abated along with the bribe amount as an operating expense.

Denmark: bribe payments are deductible when a clear operational context exists and its adequacy is maintained.

France: basically all operating expenses can be deducted. However, staff costs must correspond to an actual work done and must not be excessive compared to the operational significance. This also applies to payments to foreign parties. Here, the receiver shall specify the name and address, unless the total amount in payments per beneficiary does not exceed 500 FF. If the receiver is not disclosed the payments are considered "rémunérations occult" and are associated with the following disadvantages:

- The business expense deduction (of the bribe money) is eliminated.

- For corporations and other legal entities, a tax penalty of 100% of the "rémunérations occult" and 75% for voluntary post declaration is to be paid.

- There may be a general fine of up 200 FF fixed per case.

Japan: in Japan, bribes are deductible as business expenses that are justified by the operation (of the company) if the name and address of the recipient is specified. This also applies to payments to foreigners. If the indication of the name is refused, the expenses claimed are not recognized as operating expenses.

Canada: there is no general rule on the deductibility or non-deductibility of kickbacks and bribes. Hence the rule is that necessary expenses for obtaining the income (contract) are deductible. Payments to members of the public service and domestic administration of justice, to officers and employees and those charged with the collection of fees, entrance fees etc. for the purpose to entice the recipient to the violation of his official duties, can not be abated as business expenses as well as illegal payments according to the Criminal Code.

Luxembourg: bribes, justified by the operation (of a company) are deductible as business expenses. However, the tax authorities may require that the payer is to designate the receiver by name. If not, the expenses are not recognized as operating expenses.

Netherlands: all expenses that are directly or closely related to the business are deductible. This also applies to expenditure outside the actual business operations if they are considered beneficial as to the operation for good reasons by the management. What counts is the good merchant custom. Neither the law nor the administration is authorized to determine which expenses are not operationally justified and therefore not deductible. For the business expense deduction it is not a requirement that the recipient is specified. It is sufficient to elucidate to the satisfaction of the tax authorities that the payments are in the interest of the operation.

Austria: bribes justified by the operation (of a company) are deductible as business expenses. However, the tax authority may require that the payer names the recipient of the deducted payments exactly. If the indication of the name is denied e.g. because of business comity, the expenses claimed are not recognized as operating expenses. This principle also applies to payments to foreigners.

Switzerland: bribe payments are tax deductible if it is clearly operation initiated and the consignee is indicated.

US: (rough résumé: "generally operational expenses are deductible if they are not illegal according to the FCPA")

UK: kickbacks and bribes are deductible if they have been paid for operating purposes. The tax authority may request the name and address of the recipient."

"Specific" legal corruption: exclusively against foreign countries

Referring to the recommendation of the above-mentioned Parliamentary Financial Commission's study,[78] the then Kohl administration (1991-1994) decided to maintain the legality of corruption against officials exclusively in foreign transactions[82] and confirmed the full deductibility of bribe money, co-financing thus a specific nationalistic corruption practice (§4 Abs. 5 Nr. 10 EStG, valid until March 19, 1999) in contradiction to the 1994 OECD recommendation.[83] The respective law was not changed before the OECD Convention also in Germany came into force (1999).[84] According to the Parliamentary Financial Commission's study, however, in 1994 most countries' corruption practices were not nationalistic and much more limited by the respective laws compared to Germany.[85]

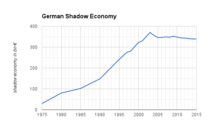

Particularly, the non-disclosure of the bribe money recipients' name in tax declarations had been a powerful instrument for Legal Corruption during the 1990s for German corporations, enabling them to block foreign legal jurisdictions which intended to fight corruption in their countries. Hence, they uncontrolled established a strong network of clientelism around Europe (e.g. SIEMENS)[86] along with the formation of the European Single Market in the upcoming European Union and the Eurozone. Moreover, in order to further strengthen active corruption the prosecution of tax evasion during that decade had been severely limited. German tax authorities were instructed to refuse any disclosure of bribe recipients' names from tax declarations to the German criminal prosecution.[87] As a result, German corporations have been systematically increasing their informal economy from 1980 until today up to 350 bn € per annum (see diagram on the right), thus continuously feeding their black money reserves.[88]

A Siemens corruption case

In 2007, Siemens was convicted in the District Court of Darmstadt of criminal corruption against the Italian corporation Enel Power SpA. Siemens had paid almost €3.5 million in bribes to be selected for a €200 million project from the Italian corporation, partially owned by the government. The deal was handled through black money accounts in Switzerland and Liechtenstein that were established specifically for such purposes.[89] Because the crime was committed in 1999, after the OECD convention had come into force, this foreign corrupt practice could be prosecuted. According to Bucerius Law School professors Frank Saliger and Karsten Gaede, for the first time a German court of law convicted foreign corrupt practices like national ones although the corresponding law did not yet protect foreign competitors in business.[90]

During the judicial proceedings however it was disclosed that numerous such black accounts had been established in the past decades.[86]

Historical responses in philosophical and religious thought

Philosophers and religious thinkers have responded to the inescapable reality of corruption in different ways. Plato, in The Republic, acknowledges the corrupt nature of political institutions, and recommends that philosophers "shelter behind a wall" to avoid senselessly martyring themselves.

- Disciples of philosophy ... have tasted how sweet and blessed a possession philosophy is, and have also seen and been satisfied of the madness of the multitude, and known that there is no one who ever acts honestly in the administration of States, nor any helper who will save any one who maintains the cause of the just. Such a savior would be like a man who has fallen among wild beasts—unable to join in the wickedness of his fellows, neither would he be able alone to resist all their fierce natures, and therefore he would be of no use to the State or to his friends, and would have to throw away his life before he had done any good to himself or others. And he reflects upon all this, and holds his peace, and does his own business. He is like one who retires under the shelter of a wall in the storm of dust and sleet which the driving wind hurries along; and when he sees the rest of mankind full of wickedness, he is content if only he can live his own life and be pure from evil or unrighteousness, and depart in peace and good will, with bright hopes.[91]

The New Testament, in keeping with the tradition of Ancient Greek thought, also frankly acknowledges the corruption of the world (ὁ κόσμος)[92] and claims to offer a way of keeping the spirit "unspotted from the world."[93] Paul of Tarsus acknowledges his readers must inevitably "deal with the world,"[94] and recommends they adopt an attitude of "as if not" in all their dealings. When they buy a thing, for example, they should relate to it "as if it were not theirs to keep."[95] New Testament readers are advised to refuse to "conform to the present age"[96] and not to be ashamed to be peculiar or singular.[97] They are advised not be friends of the corrupt world, because "friendship with the world is enmity with God."[98] They are advised not to love the corrupt world or the things of the world.[99] The rulers of this world, Paul explains, "are coming to nothing"[100] While readers must obey corrupt rulers in order to live in the world,[101] the spirit is subject to no law but to love God and love our neighbors as ourselves.[102] New Testament readers are advised to adopt a disposition in which they are "in the world, but not of the world."[103] This disposition, Paul claims, shows us a way to escape "slavery to corruption" and experience the freedom and glory of being innocent "children of God."[104]

See also

References

- ↑ Corruption can be illegal, but also can involve legal conduct in many countries. See Black's Law Dictionary for legal definition. See also worldbank.org paper noting that corruption "may involve collusion between parties typically both from the public and private sectors, and may be legal in many countries"

- ↑ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWBIGOVANTCOR/Resources/Legal_Corruption.pdf

- ↑ Morris, S.D. (1991), Corruption and Politics in Contemporary Mexico. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa

- ↑ Senior, I. (2006), Corruption – The World’s Big C., Institute of Economic Affairs, London

- 1 2 Kaufmann, Daniel; Vicente, Pedro (2005). "Legal Corruption" (PDF). World Bank.

- ↑ Locatelli, Giorgio; Mariani, Giacomo; Sainati, Tristano; Greco, Marco (2017-04-01). "Corruption in public projects and megaprojects: There is an elephant in the room!". International Journal of Project Management. 35 (3): 252–268. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.09.010.

- ↑ Elliott, Kimberly Ann (1997). "Corruption as an international policy problem: overview and recommendations" (PDF). Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

- ↑ "Material on Grand corruption" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- ↑ Alt, James. "Political And Judicial Checks On Corruption: Evidence From American State Governments" (PDF). Projects at Harvard. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-03.

- ↑ "Glossary". U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ↑ Lorena Alcazar, Raul Andrade (2001). Diagnosis corruption. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-1-931003-11-7

- ↑ Znoj, Heinzpeter (2009). "Deep Corruption in Indonesia: Discourses, Practices, Histories". In Monique Nuijten, Gerhard Anders. Corruption and the secret of law: a legal anthropological perspective. Ashgate. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0-7546-7682-9.

- ↑ Legvold, Robert (2009). "Corruption, the Criminalized State, and Post-Soviet Transitions". In Robert I. Rotberg. Corruption, global security, and world orde. Brookings Institution. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8157-0329-7.

- ↑ Merle, Jean-Christophe, ed. (2013). "Global Challenges to Liberal Democracy". Spheres of Global Justice. 1: 812.

- ↑ Pogge, Thomas. "Severe Poverty as a Violation of Negative Duties". thomaspogge.com. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alexander (2013). "Small is beautiful, at least in high-income democracies: the distribution of policy-making responsibility, electoral accountability, and incentives for rent extraction" (PDF). World Bank.

- ↑ "SOS, Missouri – State Archives Publications". Sos.mo.gov. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Hamilton, A.; Hudson, J. (2014). "Bribery and Identity: Evidence from Sudan" (PDF). Bath Economic Research Papers, No 21/14.

- ↑ Barenboim, Peter (October 2009). Defining the rules. Issue 90. The European Lawyer.

- ↑ Pahis, Stratos (2009). "Corruption in Our Courts: What It Looks Like and Where It Is Hidden". The Yale Law Journal. 118. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2013). Recruitment and Admissions: Fostering Transparency on the Path to Higher Education. In Transparency International: Global Corruption Report: Education (pp. 148–54). New York: Routledge, 536 p.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2015). Global and Local: Standardized Testing and Corruption in Admissions to Ukrainian Universities. In Carolyn A. Brown (Ed.). Globalisation, International Education Policy, and Local Policy Formation (pp. 215–34). New York: Springer.

- 1 2 3 "ararat.osipian".

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2013). Corrupt Organizations: Modeling Educators’ Misconduct with Cellular Automata. Computational & Mathematical Organization Theory, 19(1), pp. 1–24.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2009). Corruption Hierarchies in Higher Education in the Former Soviet Bloc. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(3), pp. 321–30.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2010). Corrupt Organizational Hierarchies in the Former Soviet Bloc. Transition Studies Review, 17(4), pp. 822–36.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2014). Will Bribery and Fraud Converge? Comparative Corruption in Higher Education in Russia and the USA. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 44(2), pp. 252–73.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2008). Corruption in Higher Education: Does it Differ Across the Nations and Why? Research in Comparative and International Education, 3(4), pp. 345–65.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2012). Grey Areas in the Higher Education Sector: Legality versus Corruptibility. Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal, 1(1), pp. 140–90.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2009). Investigating Corruption in American Higher Education: The Methodology. FedUni Journal of Higher Education, 4(2), pp. 49–81.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2010). Corruption in the Politicized University: Lessons for Ukraine’s 2010 Presidential Elections. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 23(2), pp. 101–14.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2012). Loyalty as Rent: Corruption and Politicization of Russian Universities. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 32(3/4), pp. 153–67.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2008). Political Graft and Education Corruption in Ukraine: Compliance, Collusion, and Control. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, 16(4), pp. 323–44.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2009). “Feed from the Service”: Corruption and Coercion in the State—University Relations in Central Eurasia. Research in Comparative and International Education, 4(2), pp. 182–203.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2012). Who is Guilty and What to Do? Popular Opinion and Public Discourse of Corruption in Russian Higher Education. Canadian and International Education Journal, 41(1), pp. 81–95.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2007). Higher Education Corruption in Ukraine: Opinions and Estimates. International Higher Education, 49, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2012). Economics of Corruption in Doctoral Education: The Dissertations Market. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), pp. 76–83.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2010). Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme: Political Corruption of Russian Doctorates. Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization, 18(3), pp. 260–80.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2014). Transforming University Governance in Ukraine: Collegiums, Bureaucracies, and Political Institutions. Higher Education Policy, 27(1), pp. 65–84.

- ↑ Osipian, Ararat. (2008). Corruption and Coercion: University Autonomy versus State Control. European Education: Issues and Studies, 40(3), pp. 27–48.

- ↑ O sipian, Ararat. (2007). Corruption in Higher Education: Conceptual Approaches and Measurement Techniques. Research in Comparative and International Education, 2(4), pp. 313–32.

- 1 2 Heyneman, S. P., Anderson, K. H. and Nuraliyeva, N. (2008). The cost of corruption in higher education. Comparative Education Review, 51, 1–25.

- 1 2 Graeff, P., Sattler, S., Mehlkop, G. and Sauer, C. (2014). "Incentives and Inhibitors of Abusing Academic Positions: Analysing University Students’ Decisions about Bribing Academic Staff" In: European Sociological Review 30(2) 230–41. 10.1093/esr/jct036

- ↑ "FBI – Italian/Mafia". Fbi.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-05-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ↑ Isaiah 1:2–31, Amos 5:21–24.

- ↑ Mt 23:13–33.

- ↑ See Ninety-five Theses.

- ↑ Kevin M. Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (2015), p. 7.

- ↑ Kevin M. Kruse, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (2015), p. 86.

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer, “On Philosophy in the Universities,” Parerga and Paralipomena, E. Payne, trans. (1974) Vol. 1, p. 141.

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer, “Sketch for a history of the doctrine of the ideal and the real,” Parerga and Paralipomena, E. Payne, trans. (1974) Vol. 1, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ "United Nations Handbook on Practical Anti-Corruption Measures For Prosecutors and Investigators" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Wang, Peng (2013). "The rise of the Red Mafia in China: a case study of organised crime and corruption in Chongqing". Trends in Organized Crime. 16 (1): 49–73. doi:10.1007/s12117-012-9179-8.

- ↑ "Just what are you trying to pull?".

- ↑ Dobos, Ned (14 September 2015). "Networking, Corruption, and Subversion". J Bus Ethics: 1–12. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2853-4 – via link.springer.com.

- ↑ "Favoritism, Cronyism, and Nepotism". Santa Clara. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- 1 2 3 Mo, P.H. (2001). Corruption and Economic Growth. Journal of Comparative Economics, 29, 66–79.

- ↑ Dimant, Eugen; Tosato, Guglielmo (2017-01-01). "Causes and Effects of Corruption: What Has Past Decade's Empirical Research Taught Us? a Survey". Journal of Economic Surveys: n/a–n/a. ISSN 1467-6419. doi:10.1111/joes.12198.

- ↑ Klitgaard, Robert (1998), Controlling Corruption, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- ↑ Stephan, Constantin (2012), Industrial Health, Safety and Environmental Management, MV Wissenschaft, Muenster, 3rd edition 2012, pp. 26–28, ISBN 978-3-86582-452-3

- ↑ "Corruption in Developing Countries".

- ↑ "IMF on OECD Convention, (page 3) Historical Background and Context" (PDF). imf.org.

- ↑ "OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Bearer of Transactions". oecd.org.

- ↑ "Country monitoring of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention". oecd.org.

- 1 2 "Forgues-Puccio, G.F. April 2013, Existing practices on anti-corruption, Economic and private sector professional evidence and applied knowledge services helpdesk request". Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ↑ Carney, Gordon Fairclough And Sean. "Czech Republic Has Its Answer to the Beverly Hills Star Tour". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Meet the strangest startup in travel: CorruptTour | CNN Travel". travel.cnn.com. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ Bilefsky, Dan (2013-08-12). "On the Crony Safari, a Tour of a City’s Corruption". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Corruption redefined as tourism in Czech Republic – BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "So much corruption, stuffed into one Chicago tour". Reuters. 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ Político*, Animal. "Tour Bus Offers Sightseeing of Emblematic Corruption Spots in Mexico City". www.insightcrime.org. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ "Using tourism to teach Mexicans about corruption". The Economist. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- ↑ Kaufmann, Daniel; Vicente, Pedro (2011). "Legal Corruption (revised)" (PDF). Economics and Politics, v23. pp. 195–219.

- ↑ Kaufmann, Daniel; Vicente, Pedro (2011). "Legal Corruption (revised)" (PDF). Economics and Politics, v23. p. 195.

- ↑ "Foreign Corrupt Practices Act". justice.gov.

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/ConvCombatBribery_ENG.pdf

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/2406452.pdf

- 1 2 3 "Drucksache 12/8468" (PDF). Bonn Parliament records. September 8, 1994. pp. 4–6.

- ↑ "YouTube".

- ↑ Drucksache 12/8468: "Die Ablehnung erfolgte mit den Stimmen der Koalitionsfraktionen gegen die Stimmen der Fraktion der SPD bei Abwesenheit der Gruppen BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN und der PDS/Linke Liste."

- ↑ § 4 chapter 5 no. 10 Income Tax Act, valid until 19 March 1999

- ↑ the term "official" had been limited to German jurisdiction. Officials of other states legally were no "officials". See "Gedächtnisschrift für Rolf Keller" Essay in Memory for Rolf Keller, 2003, Edited by Criminal Law professors from the Law Faculty of Tübingen and the Ministry of Justice of Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany, page 104: "Nach der Legaldefinition des §11 I Nr.2a StGB versteht man unter einem Amtsträger u.a. eine Person, die >>nach deutschem Recht Beamter oder Richter ist. Die Vorschrift enthält also eine vom Wortlaut her eindeutige Einschränkung auf das deutsche Recht. Ausländische Amtsträger werden somit nicht erfasst."

- ↑ OECD: Recommendation of the Council on Bribery in International Business Transactions

- ↑ Britta Bannenberg, Korruption in Deutschland und ihre strafrechtliche Kontrolle, page VII (Introduction): "Durch die OECD-Konvention und europaweite Abkommen wurden auch in Deutschland neue Anti-Korruptions-Gesetze geschaffen, so dass nun die Auslandsbestechung durch deutsche Unternehmen dem Strafrecht unterfällt und die Bestechungsgelder nicht mehr als Betriebsausgaben von der Steuer abgesetzt werden können."

- ↑ Parliamentary Financial Commission's study 1994, pp. 6–7: "Nach Auffassung der Fraktion der SPD belegt auch der Bericht der Bundesregierung eindeutig, daß in den meisten ausländischen Industriestaaten Schmier- und Bestechungsgelder in wesentlich geringerem Umfang als in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland steuerlich abgesetzt werden könnten. So müsse in fast allen Staaten bei Zahlungen in das Ausland der Empfänger angegeben werden... Die Abzugsfähigkeit der genannten Ausgaben (Schmier- und Bestechungsgelder) stelle eine steuerliche Subvention dar..."

- 1 2 "HRRS Februar 2008: Saliger/Gaede - Rückwirkende Ächtung der Auslandskorruption und Untreue als Korruptionsdelikt - Der Fall Siemens als Start-schuss in ein entgrenztes internationalisiertes Wirtschaftsstrafrecht? · hrr-strafrecht.de". hrr-strafrecht.de.

- ↑ Transparency International: "Geschützt durch das Steuergeheimnis dürfen die Steuerbehörden Hinweise auf Korruption nicht an die Staatsanwaltschaft melden."

- ↑ "Schattenwirtschaft – Umfang in Deutschland bis 2015 – Statistik". Statista.

- ↑ "HRRS Februar 2008: Saliger/Gaede – Rückwirkende Ächtung der Auslandskorruption und Untreue als Korruptionsdelikt – Der Fall Siemens als Start-schuss in ein entgrenztes internationalisiertes Wirtschaftsstrafrecht? – hrr-strafrecht.de". hrr-strafrecht.de.

- ↑ "HRRS Februar 2008: Saliger/Gaede - Rückwirkende Ächtung der Auslandskorruption und Untreue als Korruptionsdelikt – Der Fall Siemens als Start-schuss in ein entgrenztes internationalisiertes Wirtschaftsstrafrecht? · hrr-strafrecht.de". hrr-strafrecht.de.

- ↑ Plato, Plato, Republic, 496d

- ↑ 2 Peter 1:4, 2:20.

- ↑ James 1:27.

- ↑ 1 Cor 7:31.

- ↑ 1 Cor 7:30.

- ↑ Romans 12:2.

- ↑ 1 Peter 2:9.

- ↑ James 4:4.

- ↑ 1 John 2:15.

- ↑ 1 Cor 2:6.

- ↑ Romans 13:1.

- ↑ Romans 13:8.

- ↑ Andrew L. Fitz-Gibbon, In the World But Not Of the World: Christian Social Thinking at the End of the Twentieth Century (2000), See also John 15:19.

- ↑ Roman 8:21.

Further reading

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Corruption |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corruption. |

- Butscher, Anke. "Corruption" (2012). University Bielefeld - Center for InterAmerican Studies.

- Cohen, Nissim (2012). Informal payments for healthcare – The phenomenon and its context. Journal of Health Economics, Policy and Law, 7 (3): 285–308.

- Garifullin Ramil Ramzievich Bribe-taking mania as one of the causes of bribery. The concept of psychological and psychotherapeutic approaches to the problem of bribery and bribe-taking mania. J. Aktualnye Problemy Ekonomiki i Prava" ("Current Problems in Economics and Law"), no. 4(24), 2012, pp. 9-15

- Heidenheimer, Arnold J. and Michael Johnston, eds. Political corruption: Concepts and contexts (2011).

- Heywood, Paul M. ed. Routledge Handbook of Political Corruption (2014)

- Mantzaris, E., Tsekeris, C. and Tsekeris, T. (2014). Interrogating Corruption: Lessons from South Africa. International Journal of Social Inquiry, 7 (1): 1–17.