Ptitim

| |

| Alternative names | Israeli couscous, Jerusalem couscous, Pearl couscous |

|---|---|

| Type | Pasta |

| Course | Side dish |

| Place of origin | Israel |

| Created by | Osem |

| Main ingredients | Wheat |

|

| |

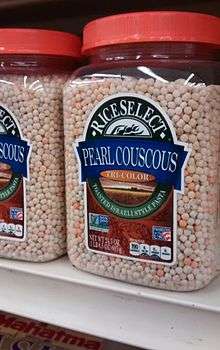

Ptitim (/ptiˈtim/; Hebrew: פתיתים, literally "flakes") is a type of toasted pasta shaped like rice grains or little balls developed in Israel in the 1950s when rice was scarce. Outside Israel, it is typically marketed as Israeli couscous, Jerusalem couscous, or pearl couscous.[1] In Israel, it originally became known as "Ben-Gurion rice" (Hebrew: אורז בן-גוריון, órez Ben-Gurion), though it is mainly called "ptitim" nowadays.

History

Ptitim was invented in 1953,[2] during the austerity period in Israel.[3] Israel's first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, asked Eugen Proper, one of the founders of the Osem food company, to quickly devise a wheat-based substitute to rice.[4] Consequently, it was nicknamed "Ben-Gurion rice" by the people.[5] The company took up the challenge and developed ptitim, which is made of hard wheat flour and toasted in an oven.[6] The product was instantly a success, after which ptitim made in the shape of small, dense balls (which the company termed "couscous") was added to the original rice-shaped ptitim.

Preparation

Ptitim is made by extruding dough through a round mold, before it is cut and toasted, giving it the uniform natural-grain-like shape[6] and its unique nutty flavor.[7] Unlike common types of pasta and couscous, ptitim was factory-made from the outset, and therefore is rarely seen home-made from scratch. The store-bought product is easy and quick to prepare.[8]

Ptitim is popular among Israeli children, who eat it plain, or mixed with fried onion and tomato paste.[4] Ptitim is now produced in ring, star, and heart shapes for added appeal.[5] For the health conscious consumers,[9] whole wheat and spelt flour varieties are also available.[4]

While considered a children's food in Israel, ptitim is sometimes used in dishes even at the "trendiest restaurants" in other countries.[5] In the United States, it can be found on the menus of contemporary American chefs, and can be bought in gourmet markets.[10]

Ptitim can be used in many different types of dishes, both hot and cold.[8] The grains retain their shape and texture even when reheated, and they do not clump together.[10] Commonly, ptitim is prepared with sautéed onions or garlic (vegetables, meat, chicken or sausage can also be added). The ptitim grains may be fried for a short time before adding water.[5] They can also be baked, go in soup, served in a pie, used for stuffing, or made as a risotto.[4] Ptitim may also be used in other dishes as a substitute for pasta or rice.[1] American chef Charlie Trotter has produced a number of recipes for ptitim-based gourmet dishes,[4] even as a dessert.[6]

Similar products

Pearl-shaped ptitim is similar to the Levantine pearled couscous, known as maftoul or moghrabieh in Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria,[11] though the two are not the same.[3] While the Levantine dish is a coated couscous, ptitim is an extruded paste.[2] The name "maftoul", however, is sometimes incorrectly used in the US to refer to ptitim.

Ptitim is also similar to the Kabyle berkoukes (aka abazine) and the Sardinian fregula, but these, too - unlike ptitim - are rolled and coated products.

The ptitim variety may also resemble some products of the pastina family, in particular acini di pepe, orzo ("risoni") and stellini. However, unlike pastina, the ptitim grains are pre-baked/toasted[11] to give them their chewy texture and nutty flavor.[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 Meador, David (14 October 2015). "Squash provides fantastic fall flavors". Living, Food & Drink: Cooking with Local Chefs. The Bradenton Herald.

- 1 2 Crum, Peggy (10 February 2010). "Featured Food: Israeli Couscous" (PDF). Recipe for Health. Residential and Hospitality Services, Michigan State University. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- 1 2 Marks, Gil (2010). "Couscous". Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 315–317. ISBN 978-0544186316.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Doram Gaunt (9 May 2008). "Ben-Gurion's Rice". Haaretz.

- 1 2 3 4 Gur, Janna (2008). "Simple Pleasures". The Book of New Israeli Food: A Culinary Journey. Schocken Books. p. 127. ISBN 978-0805212242.

- 1 2 3 4 Martinelli, Katherine (3 November 2010). "Ben Gurion’s Rice and a Tale of Israeli Invention". Food. The Forward.

- ↑ "Stocking Your Fridge and Pantry". What Good Cooks Know: 20 Years of Test Kitchen Expertise in One Essential Handbook. America's Test Kitchen. 2016. p. 134. ISBN 978-1940352664.

- 1 2 Callard, Abby (22 March 2010). "Newly Obsessed With Israeli Couscous". Arts & Culture. Smithsonian. Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Sharon Wrobel (6 July 2006). "Half of Israeli households buy low-fat products". The Jerusalem Post.

- 1 2 Faye Levy (5 October 2007). "Petit ptitim". The Jerusalem Post.

- 1 2 "Israeli Couscous". GourmetSleuth.com. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ptitim. |