High-dose estrogen

| High-dose estrogen | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

|

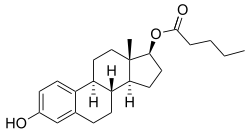

Estradiol valerate, an estrogen which has been used as a means of HDE. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Pseudopregnancy (when used in combination with a progestogen) |

| ATC code | G03C |

| Biological target | Estrogen receptors (ERα, ERβ, mERs (e.g., GPER, others)) |

| Chemical class | Steroidal; Nonsteroidal |

High-dose estrogen (HDE) is a type of hormone therapy in which high doses of estrogens are given.[1] When given in combination with a high dose of a progestogen, it has been referred to as pseudopregnancy.[2][3][4][5] It is called this because the estrogen and progestogen levels achieved are in the range of the very high levels of these hormones that occur during pregnancy.[6] HDE and pseudopregnancy have been used in medicine for a number of hormone-dependent indications, such as breast cancer, prostate cancer, and endometriosis, among others.[1][7][2] Both natural or bioidentical estrogens and synthetic estrogens have been used and both oral and parenteral routes may be used.[8][9]

Medical uses

HDE and/or pseudopregnancy have been used in clinical medicine for the following indications:

- Estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer in women[1]

- As a means of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia in men[7][8][10]

- With a high dose of a progestogen for endometriosis in women[11][12]

- Osteopenia and osteoporosis in women[3]

- Prevention of tall stature in tall adolescent girls[13]

- Suppression of IGF-1 levels in acromegaly and gigantism[14]

- As a component of hormone therapy for transgender women[15]

- Breast hypoplasia or as a means of hormonal breast enhancement in women[16][17]

- Uterine hypoplasia in women[18][3][4]

- Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in women[19]

- Postpartum depression and psychosis in women[20][21]

The nonsteroidal estrogen diethylstilbestrol as well as other stilbestrols were previously to support pregnancy and reduce the risk of miscarriage, but subsequent research found that diethylstilbestrol was both ineffective and teratogenic.[22]

HDE should be combined with a progestogen in women with an intact uterus as unopposed estrogen, particularly at high dosages/levels, increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer.[23] The majority of women with an intact uterus will develop endometrial hyperplasia within a few years of estrogen treatment even with mere replacement dosages of estrogen if a progestogen is not taken concomitantly.[23] The addition of a progestogen to estrogen nearly abolishes the increase in risk.[24]

Research

Pseudopregnancy has been suggested for use in decreasing the risk of breast cancer in women, though this has not been assessed in clinical studies.[25] Natural pregnancy before the age of 20 has been associated with a 50% lifetime reduction in the risk of breast cancer.[26] Pseudopregnancy has been found to produce decreases in risk of mammary gland tumors in rodents similar to those of natural pregnancy, implicating high levels of estrogen and progesterone in this effect.[26]

Adverse effects

General adverse effects of HDE may include breast enlargement, breast pain and tenderness, nipple enlargement and hyperpigmentation, nausea and vomiting, headache, fluid retention, edema, melasma, hyperprolactinemia, galactorrhea, amenorrhea, reversible infertility, and others. More rare and serious side effects may include thrombus and thrombosis (e.g., venous thromboembolism), prolactinoma, cholestatic jaundice, gallbladder disease, and gallstones. In women, HDE may cause amenorrhea and rarely endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, but the risk of adverse endometrial changes is minimized or offset with pseudopregnancy regimens due to the progestogen component. The tolerability profile of HDE is worse in men compared to women. Side effects of HDE specific to men may include gynecomastia (breast development), feminization and demasculinization in general (e.g., reduced body hair, decreased muscle mass and strength, feminine changes in fat mass and distribution, and reduced penile and testicular size), and sexual dysfunction (e.g., reduced libido and erectile dysfunction).

Pharmacology

When used in high doses, estrogens are powerful antigonadotropins, strongly inhibiting secretion of the gonadotropins luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone from the pituitary gland, and in men are able to completely suppress gonadal androgen production and reduce testosterone levels into the castrate range.[27] This is most of the basis of their use in prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia.[27][28] When estradiol or an estradiol ester is used for HDE in men, levels of estradiol of at least approximately 200 pg/mL are necessary to suppress testosterone levels into the castrate range.[29]

Synthetic and nonsteroidal estrogens like ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol are resistant to hepatic metabolism and for this reason have dramatically increased local potency in the liver.[30][9][31] As a result, they have disproportionate effects on hepatic protein production and a strongly increased risk of blood clots relative to endogenous and bioidentical forms of estrogen like estradiol and estradiol esters.[32] Unlike synthetic estrogens, bioidentical estrogens are efficiently inactivated in the liver even at high dosages or high circulating levels, as in pregnancy.[30][9][31]

An example pseudopregnancy regimen in women which has been used in a few clinical studies is weekly intramuscular injections of 40 mg estradiol valerate and 250 mg hydroxyprogesterone caproate.[3] It has been found to produce circulating estradiol levels of 3028–3226 pg/mL after three months and 2491–2552 pg/mL after six months of treatment in peri- and postmenopausal and hypogonadal women, from a baseline of 27.8–34.8 pg/mL.[3]

Levels of estrogen and progesterone in normal human pregnancy are very high. Estradiol levels are 1,000–5,000 pg/mL during the first trimester, 5,000–15,000 pg/mL during the second trimester, and 10,000–40,000 pg/mL during the third trimester,[33] with a mean of 25,000 pg/mL at term and levels as high as 75,000 pg/mL measurable in some women.[34] Levels of progesterone are 10–50 ng/mL in the first trimester and rise to 50–280 ng/mL in the third trimester,[35] with a mean of around 150 ng/mL at term.[36] Although only a small fraction of estradiol and progesterone are unbound in circulation, the amounts of free and thus biologically active estradiol and progesterone increase to similarly large extents as total levels during pregnancy.[36] As such, pregnancy is a markedly hyperestrogenic and hyperprogestogenic state.[37][38] Levels of estradiol and progesterone are both up to 100-fold higher during pregnancy than during normal menstrual cycling.[39]

History

HDE has been used since the discovery and introduction of estrogens in the 1930s.[39] It was first found to be effective in the treatment of breast cancer in 1944.[1][40] Pseudopregnancy was developed in the 1950s following the introduction of progestins with improved potency and pharmacokinetics.[3][4]

List of HDEs

The following steroidal estrogens have been used in HDE therapy:[1][41][28]

- Conjugated equine estrogens (Premarin)

- Estradiol and estradiol esters (e.g., estradiol benzoate, estradiol cypionate, estradiol undecylate, estradiol valerate, polyestradiol phosphate)

- Estramustine phosphate (an estradiol ester that is also an alkylating antineoplastic agent; used for prostate cancer only)

- Ethinylestradiol, its ether mestranol, and its ester ethinylestradiol sulfonate

As well as the following nonsteroidal estrogens (which are now little or not at all used):[41]

- Diethylstilbestrol (stilbestrol), fosfestrol (diethylstilbestrol diphosphate), bifluranol, and other stilbestrols

Progestogens that have been used in pseudopregnancy regimens include hydroxyprogesterone caproate, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and cyproterone acetate among others.[2] Progesterone has been little-used for such purposes likely due to its poor pharmacokinetics (e.g., low oral bioavailability and short terminal half-life).[42]

See also

- Hormone replacement therapy

- Estrogen deprivation therapy

- Hyperestrogenism

- Anabolic–androgenic steroid

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coelingh Bennink HJ, Verhoeven C, Dutman AE, Thijssen J (2017). "The use of high-dose estrogens for the treatment of breast cancer". Maturitas. 95: 11–23. PMID 27889048. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.10.010.

- 1 2 3 Victor Gomel; Andrew Brill (27 September 2010). Reconstructive and Reproductive Surgery in Gynecology. CRC Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-84184-757-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ulrich U, Pfeifer T, Lauritzen C (1994). "Rapid increase in lumbar spine bone density in osteopenic women by high-dose intramuscular estrogen-progestogen injections. A preliminary report". Horm. Metab. Res. 26 (9): 428–31. PMID 7835827. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001723.

- 1 2 3 Ulrich, U.; Pfeifer, T.; Buck, G.; Keckstein, J.; Lauritzen, C. (1995). "High-dose estrogen-progestogen injections in gonadal dysgenesis, ovarian hypoplasia, and androgen insensitivity syndrome: Impact on bone density". Adolescent and Pediatric Gynecology. 8 (1): 20–23. ISSN 0932-8610. doi:10.1016/S0932-8610(12)80156-3.

- ↑ Kistner, Robert W. (1959). "The Treatment of Endometriosis by Inducing Pseudopregnancy with Ovarian Hormones". Fertility and Sterility. 10 (6): 539–556. ISSN 0015-0282. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)33602-0.

- ↑ Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1059–1060. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- 1 2 Oh WK (2002). "The evolving role of estrogen therapy in prostate cancer". Clin Prostate Cancer. 1 (2): 81–9. PMID 15046698.

- 1 2 Lycette JL, Bland LB, Garzotto M, Beer TM (2006). "Parenteral estrogens for prostate cancer: can a new route of administration overcome old toxicities?". Clin Genitourin Cancer. 5 (3): 198–205. PMID 17239273. doi:10.3816/CGC.2006.n.037.

- 1 2 3 von Schoultz B, Carlström K, Collste L, Eriksson A, Henriksson P, Pousette A, Stege R (1989). "Estrogen therapy and liver function--metabolic effects of oral and parenteral administration". Prostate. 14 (4): 389–95. PMID 2664738.

- ↑ Turo R, Smolski M, Esler R, Kujawa ML, Bromage SJ, Oakley N, Adeyoju A, Brown SC, Brough R, Sinclair A, Collins GN (2014). "Diethylstilboestrol for the treatment of prostate cancer: past, present and future". Scand J Urol. 48 (1): 4–14. PMID 24256023. doi:10.3109/21681805.2013.861508.

- ↑ Moghissi KS (1999). "Medical treatment of endometriosis". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 42 (3): 620–32. PMID 10451774.

- ↑ Moghissi KS (1990). "Pseudopregnancy induced by estrogen-progestogen or progestogens alone in the treatment of endometriosis". Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 323: 221–32. PMID 2137617.

- ↑ Albuquerque EV, Scalco RC, Jorge AA (2017). "MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Diagnostic and therapeutic approach of tall stature". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 176 (6): R339–R353. PMID 28274950. doi:10.1530/EJE-16-1054.

- ↑ Duarte FH, Jallad RS, Bronstein MD (2016). "Estrogens and selective estrogen receptor modulators in acromegaly". Endocrine. 54 (2): 306–314. PMID 27704479. doi:10.1007/s12020-016-1118-z.

- ↑ Smith KP, Madison CM, Milne NM (2014). "Gonadal suppressive and cross-sex hormone therapy for gender dysphoria in adolescents and adults". Pharmacotherapy. 34 (12): 1282–97. PMID 25220381. doi:10.1002/phar.1487.

- ↑ Gunther Göretzlehner; Christian Lauritzen; Thomas Römer; Winfried Rossmanith (1 January 2012). Praktische Hormontherapie in der Gynäkologie. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4.

Die Unterentwicklung (Mammahypoplasie) der Brüste ist bei allgemeinem Infantilismus, aber auch bei regelmäßigem biphasischem Zyklus mit normaler Fertilität zu finden. Bei Infantilismus und gleichzeitiger Zyklusanomalie kann durch eine Pseudogravidität oder eine hochdosierte Zweiphasentherapie die bis dahin verzögerte Mammaentwicklung induziert werden. Bei Frauen mit einem normalen Zyklus kann durch Sexualsteroide, gleichgültig ob sie lokal, oral oder parenteral Anwendung finden, in knapp 70% der Fälle eine Vergrößerung der Mammae bis zu 30% des Ausgangsvolumens erreicht werden. Nach Absetzen der Hormonbehandlung besteht eine Tendenz zur Rückbildung der Volumenzunahme. Diese kann durch lokale Behandlung oder Verordnung von Östrogen-GestagenSequenzpräparaten vermindert werden. Die Größenzunahme der Mammae beruht auf Zunahme des Fettgewebes, einer verstärkten Wassereinlagerung und einer mäßigen Hypertrophie des Drüsengewebes (Tab. 6.1 und 6.2). Als Gestagene sind Progesteron-Derivate anzuwenden. Vor Behandlungsbeginn sind die Kontraindikationen für Östrogene und Gestagene auszuschließen.

- ↑ Hartmann BW, Laml T, Kirchengast S, Albrecht AE, Huber JC (1998). "Hormonal breast augmentation: prognostic relevance of insulin-like growth factor-I". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 12 (2): 123–7. PMID 9610425.

- ↑ KAISER R (1959). "[Therapeutic pseudopregnancy]". Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd (in German). 19: 593–604. PMID 13853204.

- ↑ Cronje WH, Studd JW (2002). "Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder". Prim. Care. 29 (1): 1–12, v. PMID 11856655.

- ↑ Gentile S (2005). "The role of estrogen therapy in postpartum psychiatric disorders: an update". CNS Spectr. 10 (12): 944–52. PMID 16344831.

- ↑ Sharma V (2003). "Pharmacotherapy of postpartum psychosis". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 4 (10): 1651–8. PMID 14521476. doi:10.1517/14656566.4.10.1651.

- ↑ Al Jishi T, Sergi C (2017). "Current perspective of diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in mothers and offspring". Reprod. Toxicol. 71: 71–77. PMID 28461243. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.04.009.

- 1 2 Alfred E. Chang; Patricia A Ganz; Daniel F. Hayes; Timothy Kinsella, Harvey I. Pass, Joan H. Schiller, Richard M. Stone, Victor Strecher (8 December 2007). Oncology: An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 928–. ISBN 978-0-387-31056-5.

- ↑ Rodolfo Paoletti; P.G. Crosignani; P. Kenemans; N.K. Wenger, Ann S. Jackson (11 July 2007). Women’s Health and Menopause: Risk Reduction Strategies — Improved Quality of Health. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-0-585-37973-9.

- ↑ Love RR (1994). "Prevention of breast cancer in premenopausal women". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monographs (16): 61–5. PMID 7999471.

- 1 2 Katz TA (2016). "Potential Mechanisms underlying the Protective Effect of Pregnancy against Breast Cancer: A Focus on the IGF Pathway". Front Oncol. 6: 228. PMC 5080290

. PMID 27833901. doi:10.3389/fonc.2016.00228.

. PMID 27833901. doi:10.3389/fonc.2016.00228. - 1 2 Waun Ki Hong; American Association for Cancer Research (2010). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine 8. PMPH-USA. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1.

- 1 2 Michael Oettel; Ekkehard Schillinger (6 December 2012). Estrogens and Antiestrogens II: Pharmacology and Clinical Application of Estrogens and Antiestrogen. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 540–. ISBN 978-3-642-60107-1.

- ↑ Stege R, Carlström K, Collste L, Eriksson A, Henriksson P, Pousette A (1988). "Single drug polyestradiol phosphate therapy in prostatic cancer". Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 11 Suppl 2: S101–3. PMID 3242384.

- 1 2 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. PMID 16112947. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875.

- 1 2 Coelingh Bennink HJ (2004). "Are all estrogens the same?". Maturitas. 47 (4): 269–75. PMID 15063479. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.11.009.

- ↑ Donna Shoupe (10 February 2011). Contraception. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-1-4443-4263-5.

- ↑ http://www.ilexmedical.com/files/PDF/Estradiol_ARC.pdf

- ↑ Troisi R, Potischman N, Roberts JM, Harger G, Markovic N, Cole B, Lykins D, Siiteri P, Hoover RN (2003). "Correlation of serum hormone concentrations in maternal and umbilical cord samples". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 12 (5): 452–6. PMID 12750241.

- ↑ http://www.ilexmedical.com/files/PDF/Progesterone_ARC.pdf

- 1 2 Hormones, Brain and Behavior, Five-Volume Set. Academic Press. 18 June 2002. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-08-053415-2.

- ↑ Arthur J. Atkinson (2012). Principles of Clinical Pharmacology. Academic Press. pp. 399–. ISBN 978-0-12-385471-1.

- ↑ Gérard Chaouat, Olivier Sandra and Nathalie Lédée (8 November 2013). Immunology of Pregnancy 2013. Bentham Science Publishers. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-60805-733-7.

- 1 2 Tony M. Plant; Anthony J. Zeleznik (15 November 2014). Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction. Academic Press. pp. 2289,2386. ISBN 978-0-12-397769-4.

- ↑ Philipp Y. Maximov; Russell E. McDaniel; V. Craig Jordan (23 July 2013). Tamoxifen: Pioneering Medicine in Breast Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-3-0348-0664-0.

- 1 2 Christoffel Jos van Boxtel; Budiono Santoso; I. Ralph Edwards (2008). Drug Benefits and Risks: International Textbook of Clinical Pharmacology. IOS Press. pp. 458–. ISBN 978-1-58603-880-9.

- ↑ Roy G. Farquharson; Mary D. Stephenson (2 February 2017). Early Pregnancy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 259–. ISBN 978-1-107-08201-4.