Pruitt–Igoe

Coordinates: 38°38′32.24″N 90°12′33.95″W / 38.6422889°N 90.2094306°W

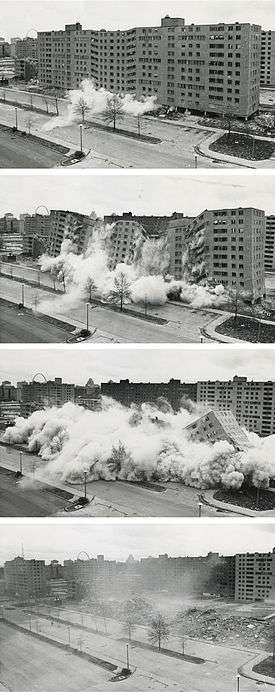

The Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and William Igoe Apartments, known together as Pruitt–Igoe, were joint urban housing projects first occupied in 1954[2] in the U.S. city of St. Louis, Missouri. Living conditions in Pruitt–Igoe began to decline soon after completion in 1956.[3] By the late 1960s, the complex had become internationally infamous for its poverty, crime, and racial segregation. All 33 buildings were demolished with explosives in the mid-1970s,[4] and the project has become an icon of failure of urban renewal and of public-policy planning.

The complex was designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki, who also designed the World Trade Center towers and the St. Louis Lambert International Airport main terminal.

History

During the 1940s and 1950s, the city of St. Louis was overcrowded, with housing conditions in some areas resembling "something out of a Charles Dickens novel."[5] Its housing stock had deteriorated between the 1920s and the 1940s, and more than 85,000 families lived in 19th century tenements. An official survey from 1947 found that 33,000 homes had communal toilets.[5] Middle-class, predominantly white, residents were leaving the city, and their former residences became occupied by low-income families. Black (north) and white (south) slums of the old city were segregated and expanding, threatening to engulf the city center.[6] To save central properties from an imminent loss of value, city authorities settled on redevelopment of the "inner ring" around the central business district.[6] As there was so much decay there, neighborhood gentrification never received serious consideration.[5]

In 1947, St. Louis planners proposed to replace DeSoto-Carr, a run-down neighborhood, with new two- and three-story residential blocks and a public park.[7] The plan did not materialize; instead, Democratic mayor Joseph Darst, elected in 1949, and Republican state leaders favored clearing the slums and replacing them with high-rise, high-density public housing. They reasoned that the new projects would help the city through increased revenues, new parks, playgrounds and shopping space.[5] Darst stated in 1951:

We must rebuild, open up and clean up the hearts of our cities. The fact that slums were created with all the intrinsic evils was everybody's fault. Now it is everybody's responsibility to repair the damage.[8]

In 1948, voters rejected the proposal for a municipal loan to finance the change, but soon the situation was changed with the Housing Act of 1949 and Missouri state laws that provided co-financing of public housing projects. The approach taken by Darst, urban renewal, was shared by the Harry S. Truman administration and fellow mayors of other cities overwhelmed by industrial workers recruited during the war.[3] Specifically, St. Louis Land Clearance and Redevelopment Authority was authorized to acquire and demolish the slums of the inner ring and then sell the land at reduced prices to private developers, fostering middle-class return and business growth. Another agency, St. Louis Housing Authority, had to clear land to construct public housing for the former slum dwellers.[6]

By 1950, St. Louis had received a federal commitment under the Housing Act of 1949[9] to finance 5,800 public housing units.[6] The first large public housing in St. Louis, Cochran Gardens, was completed in 1953 and intended for low-income whites. It contained 704 units in 12 high-rise buildings[3] and was followed by Pruitt–Igoe, Darst-Webbe and Vaughn. Pruitt–Igoe was intended for young middle-class white and black tenants, segregated into different buildings, Darst-Webbe for low-income white tenants. Missouri public housing remained racially segregated until 1956.[10]

Design and construction

In 1950, the city commissioned the firm of Leinweber, Yamasaki & Hellmuth to design Pruitt–Igoe, a new complex named for St. Louisans Wendell O. Pruitt, an African-American fighter pilot in World War II, and William L. Igoe, a former U.S. Congressman. Originally, the city planned two partitions: Captain W. O. Pruitt Homes for the black residents, and William L. Igoe Apartments for whites.[11] The site was bound by Cass Avenue on the north, North Jefferson Avenue on the west, Carr Street on the south, and North 20th Street on the east.[6]

The project was designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki who would later design New York's World Trade Center. It was Yamasaki's first large independent job, performed under supervision and constraints imposed by the federal authorities. The initial proposal provided a mix of high-rise, mid-rise and walk-up buildings. It was acceptable to St. Louis authorities, but exceeded the federal cost limits imposed by the PHA; the agency intervened and imposed a uniform building height at 11 floors.[6][11] Shortages of materials caused by the Korean War and tensions in the Congress further tightened PHA controls.[6]

In 1951, an Architectural Forum article titled "Slum Surgery in St. Louis" praised Yamasaki's original proposal as "the best high apartment" of the year.[12] Overall density was set at a moderate level of 50 units per acre (higher than in downtown slums[6]), yet, according to the planning principles of Le Corbusier and the International Congresses of Modern Architects, residents were raised up to 11 floors above ground in an attempt to save the grounds and ground floor space for communal activity.[13] Architectural Forum praised the layout as "vertical neighborhoods for poor people".[8] Each row of buildings was supposed to be flanked by a "river of trees",[13] developing a Harland Bartholomew concept.[11]

As completed in 1955, Pruitt–Igoe consisted of 33 11-story apartment buildings on a 57-acre (23 ha) site,[14] on St. Louis's lower north side. The complex totaled 2,870 apartments, one of the largest in the country.[10] The apartments were deliberately small, with undersized kitchen appliances.[10] "Skip-stop" elevators stopped only at the first, fourth, seventh, and tenth floors, forcing residents to use stairs in an attempt to lessen congestion. The same "anchor floors" were equipped with large communal corridors, laundry rooms, communal rooms and garbage chutes.[13]

Despite federal cost-cutting regulations, Pruitt–Igoe initially cost $36 million,[15] 60% above national average for public housing.[10] Conservatives attributed cost overruns to inflated unionized labor wages and the steamfitters union influence that led to installation of an expensive heating system;[10] overruns on the heating system caused a chain of arbitrary cost cuts in other vital parts of the building.[11]

Nevertheless, Pruitt–Igoe was initially seen as a breakthrough in urban renewal.[8] Residents considered it to be "an oasis in the desert" compared to the extremely poor quality of housing they had occupied previously, and considered it to be safe. Some referred to the apartments as "poor man's penthouses".[16]

Despite poor build quality, material suppliers cited Pruitt–Igoe in their advertisements, capitalizing on the national exposure of the project.[8]

Decay

On December 7, 1955, in a decision by Federal District Judge George H. Moore, St. Louis and the St. Louis housing authority were ordered to stop their practice of segregation in public housing.[17] In 1957, occupancy of Pruitt–Igoe peaked at 91%, after which it began to decline.[14] Sources differ on how quickly depopulation occurred: according to Ramroth, vacancy rose to one-third capacity by 1965;[15] according to Newman, after a certain point occupancy never rose above 60%.[13] All authors agree that by the end of the 1960s, Pruitt–Igoe was nearly abandoned and had deteriorated into a decaying, dangerous, crime-infested neighborhood; its architect lamented: "I never thought people were that destructive".[18]

Residents cite a lack of maintenance almost from the very beginning, including the regular breakdown of elevators, as being a primary cause of the deterioration of the project.[16] Local authorities cited a lack of funding to pay for the workforce necessary for proper upkeep of the buildings.[16] In addition, ventilation was poor, and centralized air conditioning nonexistent.[10] The stairwells and corridors attracted muggers.[10] The project's parking and recreation facilities were inadequate; playgrounds were added only after tenants petitioned for their installation.

In 1971, Pruitt–Igoe housed only six hundred people in seventeen buildings; the other sixteen buildings were boarded up.[19] Meanwhile, adjacent Carr Village, a low-rise area with a similar demographic makeup, remained fully occupied and largely trouble-free throughout the construction, occupancy and decline of Pruitt–Igoe.[20]

Despite decay of the public areas and gang violence, Pruitt–Igoe contained isolated pockets of relative well-being throughout its worst years. Apartments clustered around small, two-family landings with tenants working to maintain and clear their common areas were often relatively successful. When corridors were shared by 20 families and staircases by hundreds, public spaces immediately fell into disrepair.[20] When the number of residents per public space rose above a certain level, none would identify with these "no man's land[s]" – places where it was "impossible to feel ... to tell resident from intruder".[20] The inhabitants of Pruitt–Igoe organized an active tenant association, bringing about community enterprises. One such example was the creation of craft rooms; these rooms allowed the women of the Pruitt–Igoe to congregate, socialize, and create ornaments, quilts, and statues for sale.

Demolition

In 1968, the federal Department of Housing began encouraging the remaining residents to leave Pruitt–Igoe.[21] In December 1971, state and federal authorities agreed to demolish two of the Pruitt–Igoe buildings with explosives. They hoped that a gradual reduction in population and building density could improve the situation; by this time, Pruitt–Igoe had consumed $57 million, an investment that could not be abandoned at once.[15] Authorities considered different scenarios and techniques to rehabilitate Pruitt–Igoe, including conversion to a low-rise neighborhood by collapsing the towers down to four floors and undertaking a "horizontal" reorganization of their layout.[15][22]

After months of preparation, the first building was demolished with an explosive detonation at 3 p.m., on March 16, 1972.[15] The second one went down April 22, 1972.[15] After more implosions on July 15, the first stage of demolition was over. As the government scrapped rehabilitation plans, the rest of the Pruitt–Igoe blocks were imploded during the following three years; and the site was finally cleared in 1976 with the demolition of the last block.

Today, the Pruitt–Igoe site is about half-covered by Gateway Middle School and Gateway Elementary School, combined magnet schools based in science and technology, as well as Pruitt Military Academy, a military-themed magnet middle school. All schools are within the St. Louis Public School district. The other half of the Pruitt–Igoe site is made up of oak and hickory woodland. The Pruitt–Igoe electrical substation is located in the center of this area. The former DeSoto-Carr slums around the Pruitt–Igoe have also been torn down and replaced with low-density, single-family housing.

Legacy

Explanations for the failure of Pruitt–Igoe are complex. It is often presented as an architectural failure.[23] However, the same architects also designed the award-winning Cochran Gardens elsewhere in St. Louis.[24]

Other critics cite social factors including economic decline of St. Louis, white flight into suburbs, lack of tenants who were employed, and politicized local opposition to government housing projects as factors playing a role in the project's decline. Pruitt–Igoe has become a frequently used textbook case in architecture, sociology and politics, "a truism of the environment and behavior literature".[24] A noted study of the families who lived in the complex was published in book form in 1970 by Harvard sociologist Lee Rainwater, titled Behind Ghetto Walls: Black Families in a Federal Slum.

Controversy over the project remains, based mostly on racial and social-class perspectives. Housing projects of similar architectural design were successful in New York, but St. Louis's fragmented political culture and declining urban core contributed to the project's failure. This was elaborated upon in the Harvard University study on public housing in American cities, and in reports by actual residents. During the Nixon Administration, Pruitt–Igoe was widely publicized as a failure of government involvement in urban renewal, and the destruction of the buildings was dramatized in the media to show the American public that government intervention in social problems only leads to waste, and to justify cutbacks on social and economic "equalization" programs. Wealthy St. Louisans had also objected strongly to the artificial racial integration, and the resulting decrease in property values.

The Pruitt–Igoe housing project was one of the first demolitions of modernist architecture; postmodern architectural historian Charles Jencks called its destruction "the day Modern architecture died."[14][25] Its failure is often seen as a direct indictment of the society-changing aspirations of the International school of architecture. Jencks used Pruitt–Igoe as an example of modernists' intentions running contrary to real-world social development,[26] though others argue that location, population density, cost constraints, and even specific number of floors were imposed by the federal and state authorities and therefore the failure of the project cannot be attributed entirely to architectural factors.[27]

Footage of the demolition of Pruitt–Igoe was notably incorporated into the film Koyaanisqatsi.[14]

Gallery

Overview

Overview Artist's conception of Pruitt–Igoe communal space

Artist's conception of Pruitt–Igoe communal space Carr Square, across the street from Pruitt–Igoe

Carr Square, across the street from Pruitt–Igoe

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Photo attribution: Ramroth, p. 166

- ↑ Checkoway, p. 245

- 1 2 3 Larsen, Kirkendall, p. 61

- ↑ Mendelssohn, Quinn, p. 163

- 1 2 3 4 5 Larsen, Kirkendall, p. 60

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bristol, 164

- ↑ Ramroth, p. 169

- 1 2 3 4 Ramroth, p. 164

- ↑ Pub.L. 81–171

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Larsen, Kirkendall, p. 62

- 1 2 3 4 Hall, p. 256

- ↑ Alexiou, p. 38–39.

- 1 2 3 4 Newman, p. 10

- 1 2 3 4 "Why the Pruitt-Igoe housing project failed". Prospero (blog). The Economist. October 15, 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ramroth, p. 165

- 1 2 3 Freidrichs, Chad and Freidrichs, Jaime. "The Pruitt-Igoe Myth: An Urban History" (TV documentary) America ReFramed on PBS World (2011)

- ↑ Leskes, Theodore (1957). "Civil Rights". The American Jewish Yearbook. 58. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - ↑ Patterson, p. 336

- ↑ Larsen, Kirkendall p. 63

- 1 2 3 Newman, p. 11

- ↑ Ramroth, p. 171

- ↑ Leonard

- ↑ Bristol, 163

- 1 2 Bristol, 168

- ↑ Jencks, p.9

- ↑ Jencks, 9

- ↑ Bristol, p. 360

Bibliography

- Alexiou, Alice Sparberg. Jane Jacobs: Urban Visionary (2006) New Brunswick: Rutgers. Toronto: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-8135-3792-4.

- Birmingham, Elizabeth (1998). "Reframing the Ruins: Pruitt–Igoe, Structural Racism, and African American Rhetoric as a Space for Cultural Critique". Positionen. 2:2.

- Bristol, Katharine (May 1991). "The Pruitt–Igoe Myth" (PDF). Journal of Architectural Education. Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. 44 (3): 163–171. ISSN 1531-314X. doi:10.1111/j.1531-314X.2010.01093.x.

- Checkoway, Barry (1985). "Revitalizing an Urban Neighborhood: A St. Louis Case Study'". The Metropolitan Midwest. Urbana/Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01114-6.

- Hall, Peter Geoffrey Hall (2004). Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, John & Sons, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-631-23252-0.

- Hoffman, Alexander von. "Why They Built the Pruitt–Igoe Project". Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University.

- Jencks, Charles (1984). The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-0571-6.

- Larsen, Lawrence Harold; Kirkendall, Richard Stewart (2004). A History of Missouri: 1953 to 2003. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1546-8.

- Leonard, Mary Delach (2003). "Pruitt–Igoe Housing Complex". St. Louis Post Dispatch, January 13, 2004.

- Mendelssohn, Robert E.; Quinn, Michael A. (1985). "Residential Patterns in a Midwesern City: The Saint Louis Experience". The Metropolitan Midwest. Urbana/Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01114-6.

- Montgomery, Roger (1985). "Pruitt–Igoe: Policy Failure or Societal Symptom". The Metropolitan Midwest. Urbana/Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01114-6.

- Newman, Oscar (1996). Creating Defensible Space. Washington, D.C.: DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7881-4528-5.

- Patterson, James T. (1997). Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945–1974. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-511797-4.

- Pipkin, John S.; et al. (1983). Remaking the City. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-677-2.

- Rainwater, Lee (2006) [1970]. Behind Ghetto Walls: Black Families in a Federal Slum. Chicago: Aldine Transaction. ISBN 978-0-202-30907-1.

- Ramroth, William G. (2007). Planning for Disaster: How Natural and Man-made Disasters Shape the Built Environment. Kaplan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4195-9373-4.

- Weisman, Leslie K. (1994). Discrimination by Design: A Feminist Critique of the Man-Made Environment. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06399-2.

Further reading

- Bristol, Kate; Montgomery, Roger (1987). Pruitt–Igoe: An Annotated Bibliography. Council of Planning Librarians. ISBN 978-0866022057.

- Cornetet, James (2013). Facadomy: A Critique on Capitalism and Its Assault on Mid-Century Modern Architecture. Process Press. ISBN 978-0988810808.

- Palahniuk, Chuck (2004) "Confessions in Stone" in Stranger Than Fiction: True Stories. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0385504489

- Wolfe, Tom (1981). From Bauhaus to Our House. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-374-15892-4., chapter 4 Escape to Islip

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pruitt-Igoe. |