Russian Provisional Government

Coordinates: 59°56′27″N 30°18′47″E / 59.9408°N 30.313°E

The Russian Provisional Government (Russian: Временное правительство России, tr. Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of Russia established immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II of the Russian Empire on 2 March [15 March, New Style] 1917.[1][2] The intention of the provisional government was the organization of elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly and its convention. The provisional government lasted approximately eight months, and ceased to exist when the Bolsheviks gained power after the October Revolution in October [November, N.S.] 1917. According to Harold Whitmore Williams the history of eight months during which Russia was ruled by the Provisional Government was the history of the steady and systematic disorganisation of the army.[3]

For most of the life of the Provisional Government, the status of the monarchy was unresolved. This was finally clarified on 1 September [14 September, N.S.], when the Russian Republic was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice.[4]

Overview

The Provisional Government was formed in Petrograd by the Provisional Committee of the State Duma and was led first by Prince Georgy Lvov and then by Alexander Kerensky. It replaced the institution of the Council of Ministers of Russia, members of which after the February Revolution presided in the Chief Office of Admiralty. At the same time the Russian Emperor Nicholas II abdicated in favor of the Grand Duke Michael who agreed that he would accept after the decision of Russian Constituent Assembly. The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures.[5] This weakness left the government open to strong challenges from both the right and the left. The Provisional Government's chief adversary on the left was the Petrograd Soviet, which tentatively cooperated with the government at first, but then gradually gained control of the army, factories, and railways.[6] The period of competition for authority ended in late October 1917, when Bolsheviks routed the ministers of the Provisional Government in the events known as the October Revolution, and placed power in the hands of the soviets, or "workers' councils," which had given their support to the Bolsheviks. The weakness of the Provisional Government is perhaps best reflected in the derisive nickname given to Kerensky: "persuader-in-chief."[7]

World recognition

| country | date |

|---|---|

| |

22 March 1917 |

| |

24 March 1917 |

| | |

| | |

Formation

The authority of the Tsar's government began disintegrating on 1 November 1916, when Milyukov attacked the Boris Stürmer government in the Duma. Stürmer was succeeded by Alexander Trepov and Nikolai Golitsyn, both Prime Ministers for only a few weeks. During the February Revolution two rival institutions, the Imperial Duma and the Petrograd Soviet, both located in the Tauride Palace, competed for power. Tsar Nicholas II abdicated on 2 March [15 March, N.S.] and Milyukov announced the committee's decision to offer the Regency to his brother, Grand Duke Michael as the next tsar.[8] Grand Duke Michael did not want to take the poisoned chalice[9] and deferred acceptance of imperial power the next day. The Provisional Government was designed to set up elections to the Assembly while maintaining essential government services, but its power was effectively limited by the Petrograd Soviet's growing authority.

Public announcement of the formation of the Provisional Government was made. It was published in Izvestia the day after its formation.[10] The announcement stated the declaration of government

- Full and immediate amnesty on all issues political and religious, including: terrorist acts, military uprisings, and agrarian crimes etc.

- Freedom of word, press, unions, assemblies, and strikes with spread of political freedoms to military servicemen within the restrictions allowed by military-technical conditions.

- Abolition of all hereditary, religious, and national class restrictions.

- Immediate preparations for the convocation on basis of universal, equal, secret, and direct vote for the Constituent Assembly which will determine the form of government and the constitution.

- Replacement of the police with a public militsiya and its elected chairmanship subordinated to the local authorities.

- Elections to the authorities of local self-government on basis of universal, direct, equal, and secret vote.

- Non-disarmament and non-withdrawal out of Petrograd the military units participating in the revolution movement.

- Under preservation of strict discipline in ranks and performing a military service - elimination of all restrictions for soldiers in the use of public rights granted to all other citizens.

It also said, "The provisional government feels obliged to add that it is not intended to take advantage of military circumstances for any delay in implementing the above reforms and measures."

Initial composition

Initial composition of the Provisional Government:

| Lvov Government | |

|---|---|

|

9th cabinet of Russia | |

| |

| Date formed | 2 March [15 March, N.S.] 1917 |

| Date dissolved | July 1917 |

| People and organisations | |

| Head of state |

Alexis II (unproclaimed) |

| Head of government | Georgy Lvov |

| Member party | Progressive Bloc |

| Status in legislature | Coalition |

| Opposition cabinet | Executive Committee of Petrograd Soviet |

| Opposition party | Socialist coalition |

| Opposition leader | Nikolay Chkheidze |

| History | |

| Incoming formation | Golitsyn |

| Outgoing formation | Kerensky I |

| Predecessor | Nikolay Golitsyn |

| Successor | Alexander Kerensky |

| Post | Name | Party | Time of appointment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minister-President and Minister of the Interior | Georgy Lvov | March 1917 | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Pavel Milyukov | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of War and Navy | Alexander Guchkov | Octobrist | March 1917 |

| Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Transport | Nikolai Nekrasov | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Minister of Trade and Industry | Alexander Konovalov | Progressist | March 1917 |

| Minister of Justice | Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | March 1917 |

| Pavel Pereverzev | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Finance | Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-Party | March 1917 |

| Andrei Shingarev | Kadet | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Education | Andrei Manuilov | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Minister of Agriculture | Andrei Shingarev | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Victor Chernov | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Labour | Matvey Skobelev | Menshevik | April 1917 |

| Minister of Food | Alexey Peshekhonov | Popular Socialists (Russia) | April 1917 |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Irakli Tsereteli | Menshevik | April 1917 |

| Ober-Procurator of the Holy Synod | Vladimir Lvov | Progressist | March 1917 |

April Crisis

On 18 April [1 May, N.S.] 1917 minister of Foreign Affairs Pavel Milyukov sent a note to the Allied governments, promising to continue the war to 'its glorious conclusion'. On 20–21 April 1917 massive demonstrations of workers and soldiers erupted against the continuation of war. Demonstrations demanded resignation of Milyukov. They were soon met by the counter-demonstrations organised in his support. General Lavr Kornilov, commander of the Petrograd military district, wished to suppress the disorders, but premier Georgy Lvov refused to resort to violence.

The Provisional Government accepted the resignation of Foreign Minister Milyukov and War Minister Guchkov, and made a proposal to the Petrograd Soviet to form a coalition government. As a result of negotiations, on 22 April 1917 agreement was reached and 6 socialist ministers joined the cabinet.

During this period the Provisional Government merely reflected the will of the Soviet, where left tendencies (Bolshevism) were gaining ground. The Government, however, influenced by the "bourgeois" ministers, tried to base itself on the right wing of the Soviet. Socialist ministers, coming under fire from their left wing Soviet associates, were compelled to pursue a double-faced policy. The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures.[5]

July crisis and second coalition government

| Kerensky First Government | |

|---|---|

|

10th cabinet of Russia | |

| |

| Date formed | July 1917 (see July Days) |

| Date dissolved | 1 September 1917 |

| People and organisations | |

| Head of state |

Grand Duke Michael (conditionally) Alexander Kerensky (de facto) |

| Head of government | Alexander Kerensky |

| Member party | Socialist-Revolutionaries |

| Status in legislature | Coalition |

| Opposition cabinet | Executive Committee of Petrograd Soviet |

| Opposition party | RSDLP |

| Opposition leader | Nikolay Chkheidze / Leon Trotsky |

| History | |

| Incoming formation | Lvov |

| Outgoing formation | Kerensky II |

| Predecessor | Georgy Lvov |

| Successor | Alexander Kerensky |

The July Days took place in Petrograd between 3–7 July [16–20 July, N.S.] 1917, when soldiers and industrial workers in the city took to the streets in opposition to the Provisional Government. After the rising was put down, the Bolsheviks were blamed for it, and their leader Vladimir Lenin went into hiding, while other leaders were arrested.[11]

The result of the events was new protracted crisis in the Provisional Government. "Bourgeois" ministers, belonging to the Constitutional Democratic Party resigned, and no cabinet could be formed to the end of the month. Finally, on 24 July [6 August, N.S.] 1917, a new coalition cabinet, composed mostly of socialists, was formed with Kerensky at its head.

Second coalition:

| Post | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Minister-President and Minister of War and Navy | Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Vice-President, Minister of Finance | Nikolai Nekrasov | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-party |

| Minister of Internal Affairs | Nikolai Avksentiev | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Minister of Transport | Piotr Yurenev | Kadet |

| Minister of Trade and Industry | Sergei Prokopovich | Non-party |

| Minister of Justice | Alexander Zarudny | Popular Socialists (Russia) |

| Minister of Education | Sergey Oldenburg | Kadet |

| Minister of Agriculture | Victor Chernov | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Minister of Labour | Matvey Skobelev | Menshevik |

| Minister of Food | Alexey Peshekhonov | Popular Socialists (Russia) |

| Minister of Health Care | Ivan Efremov | |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Alexei Nikitin | Menshevik |

| Ober-Procurator of the Holy Synod | Vladimir Lvov | Progressist |

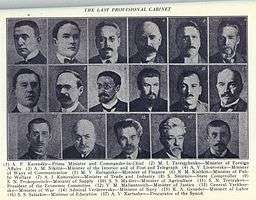

Third coalition

From 25 September [8 October, N.S.] 1917.

| Post | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Minister-President | Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Vice-President, Minister of Trade and Industry | Alexander Konovalov | Kadets |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-party |

| Minister of Internal Affairs, Post and Telegraph | Alexei Nikitin | Menshevik |

| Minister of War | Alexander Verkhovsky | |

| Minister of Navy | Dmitry Verderevsky | |

| Minister of Finance | Mikhail Bernatsky | |

| Minister of Justice | Pavel Malyantovitch | Menshevik |

| Minister of Transport | Alexander Liverovsky | Non-party |

| Minister of Education | Sergei Salazkin | Non-party |

| Minister of Agriculture | Semen Maslov | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Minister of Labour | Kuzma Gvozdev | Menshevik |

| Minister of Food | Sergei Prokopovich | Non-party |

| Minister of Health Care | Nikolai Kishkin | Kadet |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Alexei Nikitin | Menshevik |

| Minister of Religion | Anton Kartashev | Kadet |

Legislative policies and problems

With the 1917 February Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication, and the formation of a completely new Russian state, Russia’s political spectrum dramatically altered. The tsarist leadership represented an authoritarian, conservative form of governance. The Kadet Party (see Constitutional Democratic Party), composed mostly of liberal intellectuals, formed the greatest opposition to the tsarist regime leading up to the February Revolution. The Kadets transformed from an opposition force into a role of established leadership, as the former opposition party held most of the power in the new Provisional Government, which replaced the tsarist regime. The February Revolution was also accompanied by further politicization of the masses. Politicization of working people led to the leftward shift of the political spectrum.

Many urban workers originally supported the socialist Menshevik Party (see Menshevik), while some, though a small minority in February, favored the more radical Bolshevik Party (see Bolshevik). The Mensheviks often supported the actions of the Provisional Government and believed that the existence of such a government was a necessary step to achieve Communism. On the other hand, the Bolsheviks violently opposed the Provisional Government and desired a more rapid transition to Communism. In the countryside, political ideology also shifted leftward, with many peasants supporting the Socialist Revolutionary Party (see Socialist-Revolutionary Party). The SRs advocated a form of agrarian socialism and land policy that the peasantry overwhelmingly supported. For the most part, urban workers supported the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks (with greater numbers supporting the Bolsheviks as 1917 progressed), while the peasants supported the Socialist Revolutionaries. The rapid development and popularity of these leftist parties turned moderate-liberal parties, such as the Kadets, into "new conservatives." The Provisional Government was mostly composed of "new conservatives," and the new government faced tremendous opposition from the left.

Opposition was most obvious with the development and dominance of the Petrograd Soviet, which represented the socialist views of leftist parties. A dual power structure quickly arose consisting of the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet. While the Provisional Government retained the formal authority to rule over Russia, the Petrograd Soviet maintained actual power. With its control over the army and the railroads, the Petrograd Soviet had the means to enforce policies.[12] The Provisional Government lacked the ability to administer its policies. In fact, local soviets, political organizations mostly of socialists, often maintained discretion when deciding whether or not to implement the Provisional Government’s laws.

Despite its short reign of power and implementation shortcomings, the Provisional Government passed very progressive legislation. The policies enacted by this moderate government (by 1917 Russian standards) represented arguably the most liberal legislation in Europe at the time. The independence of Church from state, the emphasis on rural self governance, and the affirmation of fundamental civil rights (such as freedom of speech, press, and assembly) that the tsarist government had periodically restricted shows the progressivism of the Provisional Government. Other policies included the abolition of capital punishment and economic redistribution in the countryside. The Provisional Government also granted more freedoms to previously suppressed regions of the Russian Empire. Poland was granted independence and Lithuania and Ukraine became more autonomous.[13]

The main obstacle and problem of the Provisional Government was its inability to enforce and administer legislative policies. Foreign policy was the one area in which the Provisional Government was able to exercise its discretion to a great extent. However, the continuation of aggressive foreign policy (for example, the Kerensky Offensive) increased opposition to the government. Domestically, the Provisional Government’s weaknesses were blatant. The dual power structure was in fact dominated by one side, the Petrograd Soviet. Minister of War Alexander Guchkov stated that "We (the Provisional Government) do not have authority, but only the appearance of authority; the real power lies with the Soviet".[14] Severe limitations existed on the Provisional Government's ability to rule.

While it was true that the Provisional Government lacked enforcement ability, prominent members within the Government encouraged bottom-up rule. Politicians such as Prime Minister Georgy Lvov favored devolution of power to decentralized organizations. The Provisional Government did not desire the complete decentralization of power, but certain members definitely advocated more political participation by the masses in the form of grassroots mobilization.

Democratization

The rise of local organizations, such as trade unions and rural institutions, and the devolution of power within Russian government gave rise to democratization. It is difficult to say that the Provisional Government desired the rise of these powerful, local institutions. As stated in the previous section, some politicians within the Provisional Government advocated the rise of these institutions. Local government bodies had discretionary authority when deciding which Provisional Government laws to implement. For example, institutions that held power in rural areas were quick to implement national laws regarding the peasantry’s use of idle land. Real enforcement power was in the hands of these local institutions and the soviets. Russian historian W.E. Mosse points out, this time period represented "the only time in modern Russian history when the Russian people were able to play a significant part in the shaping of their destinies".[15] While this quote romanticizes Russian society under the Provisional Government, the quote nonetheless shows that important democratic institutions were prominent in 1917 Russia.

Special interest groups also developed throughout 1917. Special interest groups play a large role in every society deemed "democratic" today, and such was the case of Russia in 1917. Many on the far left would argue that the presence of special interest groups represent a form of bourgeois democracy, in which the interests of an elite few are represented to a greater extent than the working masses. The rise of special interest organizations gave people the means to mobilize and play a role in the democratic process. While groups such as trade unions formed to represent the needs of the working classes, professional organizations were also prominent.[16] Professional organizations quickly developed a political side to represent member’s interests. The political involvement of these groups represents a form of democratic participation as the government listened to such groups when formulating policy. Such interest groups played a negligible role in politics before February 1917 and after October 1917.

While professional special interest groups were on the rise, so too were worker organizations, especially in the cities. Beyond the formation of trade unions, factory committees of workers rapidly developed on the plant level of industrial centers. The factory committees represented the most radical viewpoints of the time period. The Bolsheviks gained their popularity within these institutions. Nonetheless, these committees represented the most democratic element of 1917 Russia. However, this form of democracy differed from and went beyond the political democracy advocated by the liberal intellectual elites and moderate socialists of the Provisional Government. Workers established economic democracy, as employees gained managerial power and direct control over their workplace. Worker self-management became a common practice throughout industrial enterprises.[17] As workers became more militant and gained more economic power, they supported the radical Bolshevik party and lifted the Bolsheviks into power in October, 1917. However, the Bolsheviks envisioned party-led control of the economy. Therefore, worker self-management, the ultimate form of economic democracy, disappeared when the Bolsheviks gained control of Russia.

Kornilov affair and declaration of Republic

The Kornilov affair was an attempted military coup d'état by the then commander-in-chief of the Russian army, General Lavr Kornilov in August 1917. Due to the extreme weakness of the government at this point, there was talk among the elites of bolstering its power by including Kornilov as a military dictator on the side of Kerensky. The extent to which this deal had indeed been accepted by all parties is still unclear. What is clear, however, is that when Kornilov's troops approached Petrograd, Kerensky branded them as counter-revolutionaries and demanded their arrest. This move can be seen as an attempt to bolster his own power by making him a defender of the revolution against a Napoleon-type figure. However, it had terrible consequences, as Kerensky's move was seen in the army as a betrayal of Kornilov, making them finally disloyal to the Provisional Government. Furthermore, as Kornilov's troops were arrested by the now armed Red Guard, it was the Soviet that was seen to have saved the country from military dictatorship. In order to defend himself and Petrograd, he provided the Bolsheviks with arms as he had little support from the army. When Kornilov did not attack Kerensky, the Bolsheviks did not return their weapons, making them a greater concern to Kerensky and the Provisional Government.

Thus far, the status of the monarchy had been unresolved. This was clarified on 1 September [14 September, N.S.], when the Russian Republic (Российская республика, Rossiyskaya respublika) was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice.[4]

The Decree read as follows:

The Coup of General Kornilov is suppressed. But the turmoil that he spread in the ranks of the army and in the country is great. Once again, a great danger threatens the fate of the country and its freedom. Considering it necessary to put an end to the uncertainty in the political system, and keeping in mind the unanimous and enthusiastic recognition of Republican ideas, which affected the Moscow State Conference, the Provisional Government announces that the state system of the Russian state is the republican system and proclaims the Russian Republic. Urgent need for immediate and decisive action to restore the shocked state system has prompted the Provisional Government to pass the power of government to five individuals from its staff, headed by the Prime Minister. The Provisional Government considers its main objective to be the restoration of public order and the fighting efficiency of the armed forces. Believing that only the concentration of all the surviving forces of the country can help the Motherland out of the difficulty in which it now finds itself, the Provisional Government will seek to expand its membership by attracting to its ranks all those who consider the eternal and general interests of the country more important than the short-term and particular needs of certain parties or classes. The Provisional Government has no doubt that it will succeed in this task in the days ahead.[4]

On 12 September [25, N.S] an All-Russian Democratic Conference was convened, and its presidium decided to create a Pre-Parliament and a Special Constituent Assembly which was to elaborate the future Constitution of Russia. This Constitutional Assembly was to be chaired by Professor N. I. Lazarev and the historian V. M. Gessen.[4] The Provisional Government was expected to continue to administer Russia until the Constituent Assembly had determined the future form of government. On 16 September 1917, the Duma) was dissolved by the newly created Directorate.

October Revolution

On 25–26 October Red Guard forces under the leadership of Bolshevik commanders launched their final attack on the ineffectual Provisional Government. Most government offices were occupied and controlled by Bolshevik soldiers on the 25th; the last holdout of the Provisional Ministers, the Tsar's Winter Palace on the Neva River bank, was captured on the night of the 26th. Kerensky escaped the Winter Palace raid and fled to Pskov, where he rallied some loyal troops for an attempt to retake the capital. His troops managed to capture Tsarskoe Selo but were beaten the next day at Pulkovo. Kerensky spent the next few weeks in hiding before fleeing the country. He went into exile in France and eventually emigrated to the U.S.

The Bolsheviks then replaced the government with their own. The Little Council (or Underground Provisional Government) met at the house of Sofia Panina briefly in an attempt to resist the Bolsheviks. However this initiative ended on 28 November with the arrest of Panina, Fyodor Kokoshkin, Andrei Ivanovich Shingarev and Prince Pavel Dolgorukov and Panina being the subject of a political trial.[18]

Some academics, such as Pavel Osinsky, argue that the October Revolution was as much a function of the failures of the Provisional Government as it was of the strength of the Bolsheviks. Osinsky described this as "socialism by default" as opposed to "socialism by design." [19]

Riasanovsky argued that the Provisional Government made perhaps its "worst mistake"[7] by not holding elections to the Constituent Assembly soon enough. They wasted time fine-tuning details of the election law, while Russia slipped further into anarchy and economic chaos. By the time the Assembly finally met, Riasanovsky noted, "the Bolsheviks had already gained control of Russia."[20]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Manifest of abdication (in Russian)

- ↑ "Announcement of the First Provisional Government, 13 March 1917". FirstWorldWar.com. 2002-12-29. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ↑ Harold Whitmore Williams (1919) The Spirit of the Russian Revolution, p. 14, 15. Russian Liberation Committee, no. 9, 173 Fleet Street. London

- 1 2 3 4 The Russian Republic Proclaimed at prlib.ru, accessed 12 June 2017

- 1 2 "Annotated chronology (notes)". University of Oregon/Alan Kimball. 2004-11-29. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ↑ Kerensky, Alexander (1927). The Catastrophe— Kerensky’s Own Story of the Russian Revolu. D. Appleton and Company. p. 126. ISBN 0-527-49100-4.

- 1 2 Riasanovsky, Nicholas (2000). A History of Russia (sixth edition). Oxford University Press. p. 457. ISBN 0-19-512179-1.

- ↑ Harold Whitmore Williams (1919), p. 3

- ↑ M. Lynch, Reaction and Revolution: Russia 1894-1924 (3rd ed.), Hodder Murray, London 2005, pg. 79

- ↑ "Announcement of the First Provisional Government, 3 March 1917". FirstWorldWar.com. 2002-12-29. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ↑ Christopher Read (2005) Lenin. London, Routledge: 160-2

- ↑ Rex A. Wade, The Russian Revolution, 1917 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 67

- ↑ W. E. Mosse, "Interlude: The Russian Provisional Government 1917," Soviet Studies 15 (1964): 411-412

- ↑ Wade, The Russian Revolution, 1917, 57

- ↑ Mosse, "Interlude: The Russian Provisional Government 1917," 414

- ↑ Matthew Rendle, "The Officer Corps, Professionalism, And Democracy In The Russian Revolution," 922

- ↑ Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 54-55

- ↑ Lindenmeyr, Adele (October 2001), "The First Soviet Political Trial: Countess Sofia Panina before the Petrograd Revolutionary Tribunal", The Russian Review, 60: 505–525, doi:10.1111/0036-0341.00188

- ↑ Osinsky, Pavel. War, State Collapse, Redistribution: Russian Revolution Revisited, Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Montreal Convention Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2006

- ↑ Riasanovsky, Nicholas (2000). A History of Russia (sixth edition). Oxford University Press. p. 458. ISBN 0-19-512179-1.

Further reading

- Abraham, Richard (1987). Kerensky: First Love of the Revolution. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-06108-0.

- Acton, Edward, et al. eds. Critical companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921 (Indiana UP, 1997).

- Hickey, Michael C. "The Provisional Government and Local Administration in Smolensk in 1917." Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography 9.1 (2016): 251-274.

- Lipatova, Nadezhda V. "On the Verge of the Collapse of Empire: Images of Alexander Kerensky and Mikhail Gorbachev." Europe-Asia Studies 65.2 (2013): 264-289.

- Orlovsky, Daniel. "Corporatism or democracy: the Russian Provisional Government of 1917." The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 24.1 (1997): 15-25.

- Thatcher, Ian D. "Post-Soviet Russian Historians and the Russian Provisional Government of 1917." Slavonic & East European Review 93.2 (2015): 315-337. online

- Thatcher, Ian D. "Memoirs of the Russian Provisional Government 1917." Revolutionary Russia 27.1 (2014): 1-21.

Primary sources

- Browder, Robert P. and Alexander F. Kerensky, eds. The Russian Provisional Government 1917 (3 vols, Stanford UP, 1961).