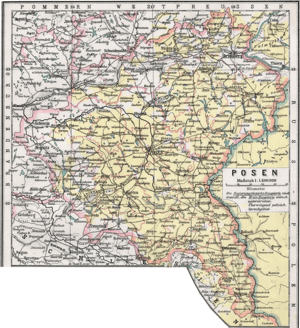

Province of Posen

| Province of Posen Provinz Posen (German) Prowincja Poznańska (Polish) | ||||||

| Province of Prussia | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

.svg.png) | ||||||

| Capital | Posen 52°24′N 16°55′E / 52.400°N 16.917°ECoordinates: 52°24′N 16°55′E / 52.400°N 16.917°E | |||||

| History | ||||||

| • | Established | 1848 | ||||

| • | Disestablished | 1919 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | 1910 | 28,970 km2 (11,185 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 1910 | 2,099,831 | ||||

| Density | 72.5 /km2 (187.7 /sq mi) | |||||

| Political subdivisions | Posen Bromberg | |||||

The Province of Posen (German: Provinz Posen, Polish: Prowincja Poznańska) was a province of Prussia from 1848 and as such part of the German Empire from 1871 until 1918. The area, roughly corresponding to the historic region of Greater Poland annexed during the 18th century Polish partitions, was about 29,000 km2 (11,000 sq mi).[1] For more than a century, it was part of the Prussian Partition, with a brief exception during the Napoleonic Wars.

Incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Posen after the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the territory was administered as a Prussian province upon the Greater Poland Uprising of 1848. In 1919 according to the Treaty of Versailles, Germany had to return the bulk of the province to the newly established Second Polish Republic.

Geography

The land is mostly flat, drained by two major watershed systems; the Noteć (German: Netze) in the north and the Warta (Warthe) in the center. Ice Age glaciers left moraine deposits and the land is speckled with hundreds of "finger lakes", streams flowing in and out on their way to one of the two rivers.

Agriculture was the primary industry, as one would expect for the 19th century. The three-field system was used to grow a variety of crops, primarily rye, sugar beet, potatoes, other grains, and some tobacco and hops. Significant parcels of wooded land provided building materials and firewood. Small numbers of livestock existed, including geese, but a fair amount of sheep were herded.

When this area came under Prussian control, the feudal system was still in force. It was officially ended in Prussia (see Freiherr vom Stein) in 1810 (1864 in Congress Poland), but lingered in some practices until the late 19th century. The situation was thus that (primarily) Polish serfs lived and worked side by side with (predominantly) free German settlers. Though the settlers were given initial advantages, in time their lots were not much different. Serfs worked for the noble lord, who took care of them. Settlers worked for themselves and took care of themselves, but paid taxes to the lord.

Typically, an estate would have its manor and farm buildings, and a village nearby for the Polish laborers. Near that village, there might be a German settlement. And in the woods, there would be a forester's dwelling. The estate owners, usually of the nobility, owned the local grist mill, and often other types of mills or perhaps a distillery. In many places, windmills dotted the landscape, reminding one of the earliest settlers, the Dutch, who began the process of turning unproductive river marshes into fields. This process was finished by the German settlers employed to reclaim unproductive lands (not only marshland) for the host estate owners.

History

The territory of later province had become Prussian in 1772 (Netze District) and 1793 (South Prussia) during the First and Second Partition of Poland. After Prussia's defeat in the Napoleonic Wars, the territory was attached to the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 upon the Franco-Prussian Treaty of Tilsit. In 1815 during the Congress of Vienna, Prussia gained the western third of the Warsaw duchy, which was about half of former South Prussia. Prussia then administered this province as the semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen, which lost most of its exceptional status already after the 1830 November Uprising in Congress Poland,[1] as the Prussian authorities feared a Polish national movement which would have swept away the Holy Alliance system in Central Europe. Instead Prussian Germanisation measures increased under Oberpräsident Eduard Heinrich von Flottwell, who had replaced Duke-governor Antoni Radziwiłł.

A first Greater Poland Uprising in 1846 failed, as the leading insurgents around Karol Libelt and Ludwik Mierosławski were reported to the Prussian police and arrested for high treason. Their trial at the Berlin Kammergericht court gained them enormous popularity even among German national liberals, who themselves were suppressed by the Carlsbad Decrees. Both were released in the March Revolution of 1848 and triumphantly carried through the streets.

At the same time, a Polish national committee gathered at Poznań and demanded independence. The Prussian Army under General Friedrich August Peter von Colomb at first retired. King Frederick William IV of Prussia as well as the new Prussian commissioner, Karl Wilhelm von Willisen, promised a renewed autonomy status.

However, both among the German-speaking population of the province as well as in the Prussian capital, anti-Polish sentiments arose. While the local Posen (Poznań) Parliament voted 26 to 17 votes against joining German Confederation, on 3 April 1848[2] the Frankfurt Parliament ignored the vote, forcing status change to a common Prussian province and its integration in the German Confederation.[3]

The Frankfurt parliamentarian Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Jordan vehemently spoke against Polish autonomy. The assembly at first attempted to divide the Posen duchy into two parts: the Province of Posen, which would have been given to the German population and annexed to a newly created Greater Germany, and the Province of Gniezno, which would have been given to the Poles and remain outside of Germany. Because of the protest of Polish politicians, this plan failed and the integrity of the duchy was preserved. Nevertheless, after the Greater Polish revolt had been finally crushed by Prussian troops, the authorities on 9 February 1849, after a series of broken assurances, renamed the duchy the Province of Posen. The "Grand Duke of Posen" remained a title held by the Hohenzollern dynasty and the name remained in official use until 1918.

With the unification of Germany after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, the Province of Posen became part of the German Empire, and the city of Posen was officially named an imperial residence city. Bismarck's hostility towards the Pole was already well known, as in 1861 had written in a letter to his sister: "Hit the Poles so hard that they despair of their life; I have full sympathy for their condition, but if we want to survive we can only exterminate them."[4] His dislike bordered on insanity and was firmly entrenched in traditions of Prussian mentality and history. While he did not write or talk about it, it pre-occupied his mind. There was little need for discussions in Prussian circles, as most of them, including the monarch, agreed with his views.[5] Poles suffered from discrimination by the Prussian state; numerous oppressive measures were implemented to eradicate the Polish community's identity and culture.[6][7]

The Polish inhabitants of Posen, who faced discrimination and even forced Germanization, favored the French side durinng the Franco-Prussian War. France and Napoleon III were known for their support and sympathy for the Poles under Prussian rule[8][9] Demonstrations at news of Prussian-German victories manifested Polish independence feelings and calls were also made for Polish recruits to desert from the Prussian Army, though these went mostly unheeded. Bismarck regarded these as an indication of a Slavic-Roman encirclement and even a threat to unified Germany.[10] Under German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck renewed Germanisation policies began, including an increase of the police, a colonization commission, and the Kulturkampf. The German Eastern Marches Society (Hakata) pressure group was founded in 1894 and in 1904, special legislation was passed against the Polish population. The legislation of 1908 allowed for the confiscation of Polish-owned property. The Prussian authorities did not permit the development of industries in Posen, so the duchy's economy was dominated by high-level agriculture.

At the end of World War I, the fate of the province was undecided. The Poles inhabitants demanded the region be included in the newly independent Second Polish Republic, while the German minority refused any territorial concessions. Another Greater Poland Uprising broke out on 27 December 1918, a day after the speech of Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The uprising received little support from the Polish government in Warsaw. After the success of the uprising, Posen province was until mid-1919 an independent state with its own government, currency and military. With the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, most of the province, composed of the areas with a Polish majority, was ceded to Poland and was reformed as the Poznań Voivodeship. The German populated remainder (with Bomst, parts of Czarnikau and Filehne, Fraustadt, Meseritz, Schneidemühl and Schwerin), about 2,200 km2, was merged with the western remains of former West Prussia and was administered as Posen-West Prussia[1] with Schneidemühl as its capital. This province was dissolved in 1938, when its territory was split between the neighboring Prussian provinces of Silesia, Pomerania and Brandenburg. In 1939, the territory of the former province of Posen was annexed by Nazi Germany and made part of Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia and Reichsgau Wartheland (initially Reichsgau Posen). By the time World War II ended in May 1945, it had been overrun by the Red Army.

Following Germany's defeat in World War in 1945, at Stalin's demand all of the German territory east of the newly established Oder–Neisse line of the Potsdam Agreement was either turned over to the Poland or the Soviet Union. All historical parts of the province came under Polish control, and the remaining ethnic German population was expelled by force.

Religious and ethnic conflicts

This region was inhabited by a Polish majority, with German and Jewish minorities and a smattering of other ethnic groups. Almost all the Poles were Roman Catholic, and about 90% of the Germans were Protestant. The small numbers of Jews were primarily in the larger communities, mostly in skilled crafts, local commerce and regional trading. The smaller a community, the more likely it was to be either all Polish or German. These "pockets of ethnicity" existed side by side, with German villages being the most dense in the northwestern areas. Under Prussia's Germanization policies, the population became more German until the end of the 19th century, when the trend reversed (in the Ostflucht). This was despite efforts of the government in Berlin to prevent it, establishing the Settlement Commission to buy land from Poles and make it available for sale only to Germans.

The province's large number of resident Germans resulted from constant immigration since the Middle Ages, when the first settlers arrived in the course of the Ostsiedlung. Although many of those had been Polonized over time, a continuous immigration resulted in maintaining a large German community. The 18th century Jesuit-led Counter-Reformation enacted severe restrictions on German Protestants. At the end of the 18th century when Prussia seized the area during the Partitions of Poland, thousands of German colonists were sent by Prussian officials to Germanize the area.

During the first half of the 19th century, the German population grew due to state sponsored colonisation.[11] In the second half, the Polish population grew gradually due to the Ostflucht and a higher birthrate among the Poles. In the Kulturkampf, mainly Protestant Prussia sought to reduce the Catholic impact on its society. Posen was hit severely by these measures due to its large, mainly Polish Catholic population. Many Catholic Germans in Posen joined with ethnic Poles in opposition to Kulturkampf measures. Following the Kulturkampf, the German Empire for nationalist reasons implemented Germanisation programs. One measure was to set up a Settlement Commission to attract German settlers to counter the Polish population's higher growth. However, this failed, even when accompanied by additional legal measures. The Polish language was eventually banned from use in schools and government offices as part of the Germanisation policies.

| Ethnic composition of the Province of Posen | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | 1815[12] | 1819[13] | 1861 | 1890[14] | 1910 |

| total population[15] | 776,000 | 883,972 | 1,467,604 | 1,751,642 | 2,099,831 |

| % Poles (including bilinguals)[16] | 73% | 77.0% | 54.6% | 60.1% | 61.5% |

| % Germans | 25% | 17.5% | 43.4% | 39.9% | 38.5% |

There is a notable disparity between German statistics gathered by the Prussian administration, and the Polish estimates conducted after 1918. According to the Prussian census of 1905, the number of German speakers in the Province of Posen was approximately 38.5%(which included colonists, military stationed in the area and German administration), while after 1918 the number of Germans in the Poznan Voivodship, which closely corresponded to province of Posen, was only 7%. According to Witold Jakóbczyk, the disparity between the number of ethnic Germans and the number of German speakers is because Prussian authorities placed ethnic Germans and the German-speaking Jewish minority into the same class.[17] In addition, there was a considerable exodus of Germans from the Second Polish Republic after the latter was established. Another reason of the disparity is that some border areas of the province, inhabited mostly by Germans (including Piła), remained in Germany after 1918.[18][19]

Statistics

Area: 28,970 km²

Population

- 1816: 820,176

- 1868: 1,537,300 (Bromberg 550,900 - Posen 986,400)

- 1871: 1,583,843

- Religion: 1871

- Catholics 1,009,885

- Protestants 511,429

- Jews 61,982

- others 547

- Religion: 1871

- 1875: 1,606,084

- 1880: 1,703,397

- 1900: 1,887,275

- 1905: 1,986,267

- 1910: 2,099,831 (Bromberg 763,900 - Posen 1,335,900)

Divisions

Prussian provinces were subdivided into government regions (Regierungsbezirke), in Posen:

- Regierungsbezirk Posen 17,503 km²

- Regierungsbezirk Bromberg 11,448 km²

These regions were again subdivided into districts called Kreise. Cities would have their own "Stadtkreis" (urban district) and the surrounding rural area would be named for the city, but referred to as a "Landkreis" (rural district). In the case of Posen, the Landkreis was split into two: Landkreis Posen West, and Landkreis Posen East.

Data is from Prussian censuses, during a period of state-sponsored Germanization, and includes military garrisons. It is often criticized as being falsified.[20]

| Kreis ("County") | Polish spelling | 1905 Pop | Polish speakers | German speakers1 | Jewish2 | Origin |

| Regierungsbezirk Posen (southern) | ||||||

| City of Posen | Poznań | 55% | 45% | |||

| Adelnau | Odolanów | 90% | 10% | |||

| Birnbaum | Miedzychód | 51% | 49% | |||

| Bomst | Babimost | 49% | 51% | |||

| Fraustadt | Wschowa | 27% | 73% | |||

| Gostyn | Gostyn | 87% | 13% | Kröben | ||

| Grätz | Grodzisk | 82% | 18% | Buk | ||

| Jarotschin | Jarocin | 83% | 17% | Pleschen | ||

| Kempen | Kępno | 84% | 16% | Schildberg | ||

| Koschmin | Koźmin | 83% | 17% | Krotoschin | ||

| Kosten | Kościan | 89% | 11% | |||

| Krotoschin | Krotoszyn | 70% | 30% | |||

| Lissa | Leszno | 36% | 64% | Fraustadt | ||

| Meseritz | Międzyrzecz | 20% | 80% | |||

| Neutomischel | Nowy Tomyśl | 51% | 49% | Buk | ||

| Obornik | Oborniki | 61% | 39% | |||

| Ostrowo | Ostrów | 80% | 20% | ?Adelnau? | ||

| Pleschen | Pleszew | 85% | 15% | |||

| Posen Ost | Poznań, Wsch. | 72% | 28% | Posen | ||

| Posen West | Poznań, Zach. | 87% | 13% | Posen | ||

| Rawitsch | Rawicz | 55% | 45% | Kröben | ||

| Samter | Szamotuły | 73% | 27% | |||

| Schildberg | Ostrzeszów | 90% | 10% | |||

| Schmiegel | Śmigiel | 82% | 18% | Kosten | ||

| Schrimm | Śrem | 82% | 18% | |||

| Schroda | Środa | 88% | 12% | |||

| Schwerin | Skwierzyna | 5% | 95% | Birnbaum - 1877 | ||

| Wreschen | Września | 84% | 16% | |||

| Regierungsbezirk Bromberg (northern) | ||||||

| City of Bromberg | Bydgoszcz | 16% | 84% | |||

| Bromberg | Bydgoszcz | 38% | 62% | |||

| Czarnikau | Czarników | 27% | 73% | |||

| Filehne | Wieleń | 28% | 72% | Czarnikau | ||

| Gnesen | Gniezno | 67% | 33% | |||

| Hohensalza | Inowrocław | 64% | 36% | |||

| Kolmar | Chodzież | 18% | 82% | |||

| Mogilno | Mogilno | 76% | 24% | |||

| Schubin | Szubin | 56% | 44% | |||

| Strelno | Strzelno | 82% | 18% | ?? | ||

| Wirsitz | Wyrzysk | 47% | 53% | |||

| Witkowo | Witkowo | 83% | 17% | ?Gnesen? | ||

| Wongrowitz | Wągrowiec | 77% | 23% | |||

| Znin | Żnin | 77% | 23% | ?? | ||

1 includes bilingual speakers

2 only religious Jews, without regard of their native language

The German figure includes the German-speaking Jewish population.

Presidents

The province was headed by presidents (German: Oberpräsidenten).

| Time in Office | Name |

| 1815–1824 | Joseph Zerboni de Sposetti 1760–1831 |

| 1825–1830 | Johann Friedrich Theodor von Baumann 1768–1830 |

| 1830–1840 | Eduard Heinrich Flottwell 1786–1865 |

| 1840–1842 | Adolf Heinrich Graf von Arnim-Boitzenburg 1803–1868 |

| 1843–1850 | Carl Moritz von Beurmann 1802–1870 |

| 1850–1851 | Gustav Carl Gisbert Heinrich Wilhelm Gebhard von Bonin (1.time in office) 1797–1878 |

| 1851–1860 | Eugen von Puttkamer 1800–1874 |

| 1860–1862 | Gustav Carl Gisbert Heinrich Wilhelm Gebhard von Bonin (2.time in office) 1797–1878 |

| 1862–1869 | Carl Wilhelm Heinrich Georg von Horn 1807–1889 |

| 1869–1873 | Otto Graf von Königsmarck 1815–1889 |

| 1873–1886 | William Barstow von Guenther 1815–1892 |

| 1886–1890 | Robert Graf von Zedtlitz-Trützschler 1837–1914 |

| 1890–1899 | Hugo Freiherr von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff 1840–1905 |

| 1899–1903 | Karl Julius Rudolf von Bitter 1846–1914 |

| 1903–1911 | Wilhelm August Hans von Waldow-Reitzenstein 1856–1937 |

| 1911–1914 | Philipp Schwartzkopf ? |

| 1914–1918 | Joh. Karl Friedr. Moritz Ferd. v. Eisenhart-Rothe 1862–1942 |

Notable people

(in alphabetical order)

(see also Notable people of Grand Duchy of Posen)

- Stanisław Adamski (1875–1967), Polish priest, social and political activist of the Union of Catholic Societies of Polish Workers (Związek Katolickich Towarzystw Robotników Polskich), founder and editor of the 'Robotnik' (Worker) weekly

- Tomasz K. Bartkiewcz (1865–1931), Polish composer and organist, co-founder of the Singer Circles Union (Związek Kół Śpiewackich)

- Wernher von Braun (1912 –1977) German rocket engineer and space architect. One of the leading figures in the development of rocket technology,from the V1 & V2 to the Saturn rocket that powered the first Moon landing. Credited as being the "Father of Rocket Science".

- Czesław Czypicki (1855–1926), Polish lawyer from Kożmin, activist for the singers' societies

- Michał Drzymała (1857–1937), famous Polish peasant

- Ferdinand Hansemann (1861–1900), Prussian politician, co-founder of the German Eastern Marches Society

- Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934), German field marshal and statesman, last President of Germany before Adolf Hitler.

- Józef Kościelski (1845–1911), Polish politician and parliamentarian, co-founder of the Straż (Guard) society

- Konstanty Kościnski, author of The Guide to Poznań and the Grand Duchy of Poznań (Przewodnik pod Poznaniu i Wielkim Księstwie Poznańskiem), Poznań 1909

- Józef Krzymiński (1858–1940), Polish physician, social and political activist, member of parliament

- Władysław Marcinkowski (1858–1947), Polish sculptor who created a monument of Adam Mickiewicz in Milosław

- Władysław Niegolewski (1819–85), Polish liberal politician and member of parliament, insurgent in 1846, 1848 and 1863, cofounder of TCL and CTG

- Cyryl Ratajski (1875–1942), president of Poznań 1922–34

- Arthur Ruppin (1876–1943), pioneering sociologist, Zionist thinker and leader, co-founder of Tel Aviv

- Karol Rzepecki (1865–1931), Polish bookseller, social and political activist, editor of Sokół (Falcon) magazine

- Antoni Stychel (1859–1935), Polish priest, member of parliament, president of the Union of the Catholic Societies of Polish Workers (Związek Katolickich Towarzystw Robotników Polskich)

- Roman Szymański (1840–1908), Polish political activist, publicist, editor of Orędownik magazine

- Aniela Tułodziecka (1853–1932), Polish educational activist of the Warta Society (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Wzajemnego Pouczania się i Opieki nad Dziećmi Warta)

- Teofil Walicki

- Piotr Wawrzyniak (1849–1910), Polish priest, economic and educational activist, patron of the Union of the Earnings and Economic Societies (Związek Spółek Zarobkowych i Gospodarczych)

References

- 1 2 3 Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der Deutschen Länder: die deutschen Territorien vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, 7th edition, C.H.Beck, 2007, p.535, ISBN 3-406-54986-1

- ↑ Andrzej Chwalba - Historia Polski 1795-1918 Wydawnictwo Literackie 2000 Kraków

- ↑ Dieter Gosewinkel, Einbürgern und Ausschliessen: die Nationalisierung der Staatsangehörigkeit vom Deutschen Bund bis zur Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2nd edition, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2001, p.116, ISBN 3-525-35165-8

- ↑ Hajo Holborn: A History of Modern Germany: 1840-1945, Volume 3, page 165

- ↑ Bismarck Edward Crankshaw pages 1685-1686 Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011

- ↑ Jerzy Zdrada - Historia Polski 1795-1918 Warsaw Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN 2007; pages 268, 273-291, 359-370

- ↑ Andrzej Chwalba - Historia Polski 1795-1918 Wydawnictwo Literackie 2000 Kraków pages 175-184, 307-312

- ↑ Bismarck: A Political History Edgar Feuchtwange page 157r

- ↑ Zarys dziejów wojskowości polskiej w latach 1864-1939 Mieczysław Cieplewicz Wydawn. Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1990, page 36

- ↑ Clark, Christopher (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise And Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Harvard University Press. p. 579.

- ↑ Preußische Ansiedlungskommission

- ↑ Historia 1789-1871 Page 224. Anna Radziwiłł and Wojciech Roszkowski.

- ↑ Hassel, Georg (1823). Statistischer Umriß der sämmtlichen europäischen und der vornehmsten außereuropäischen Staaten, in Hinsicht ihrer Entwickelung, Größe, Volksmenge, Finanz- und Militärverfassung, tabellarisch dargestellt; Erster Heft: Welcher die beiden großen Mächte Österreich und Preußen und den Deutschen Staatenbund darstellt; Nationalverschiedenheit 1819: Polen - 680,100; Deutsche - 155,000; Juden - 48,700. Verlag des Geographischen Instituts Weimar. p. 43.

- ↑ Scott M. Eddie, Ethno-nationality and property rights in land in Prussian Poland, 1886-1918, Buying the land from under the Poles' feet? in S. Engerman, Land rights, ethno-nationality and sovereignty in history, 2004, p.57,

- ↑ Leszek Belzyt: Sprachliche Minderheiten im preußischen Staat 1815–1914. Marburg 1998, S.17

- ↑ Leszek Belzyt: Sprachliche Minderheiten im preußischen Staat 1815–1914. Marburg 1998, S.17f. ISBN 3-87969-267-X

- ↑ "Dzieje Wielkopolski" (red. Witold Jakóbczyk)

- ↑ Blanke, Richard (1993). Orphans of Versailles: the Germans in Western Poland, 1918-1939. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 33–34. ISBN 0-8131-1803-4. Retrieved 2009-09-05.

- ↑ Stefan Wolff, The German Question Since 1919: An Analysis with Key Documents, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, p.33, ISBN 0-275-97269-0

- ↑ Spisy ludności na ziemiach polskich do 1918 r

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Posen (province). |