The Providence Journal

|

The July 27, 2005 front page of The Providence Journal | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Owner(s) | Local Media Group |

| Publisher | Janet Hasson |

| Founded | July 1, 1829[1] |

| Headquarters |

75 Fountain Street Providence, Rhode Island 02902 |

| Circulation |

70,600 Mon.-Sat.[2] 89,452 Sunday[3] |

| Website | providencejournal.com |

The Providence Journal, nicknamed the ProJo, is a daily newspaper serving the metropolitan area of Providence, Rhode Island and is the largest newspaper in Rhode Island. The newspaper was first published in 1829 and is the oldest continuously-published daily newspaper in the United States. The newspaper has won four Pulitzer Prizes.

History

The Journal bills itself as "America's oldest daily newspaper in continuous publication,"[1] a distinction that comes from the fact that The Hartford Courant, started in 1764, did not become a daily until 1837 and The New York Post, which began daily publication in 1801, had to suspend publication during strikes in 1958 and 1978.[4]

The paper's history has reflected the waxing and waning of newspaper popularity throughout the United States.

Early Years

The beginnings of the Providence Journal Company started on January 3, 1820, when publisher "Honest" John Miller started the Manufacturers' & Farmers' Journal, Providence & Pawtucket Advertiser in Providence, published twice per week.[5]

By 1829, demand for more timely news caused Miller to combine his existing publications into the Providence Daily Journal, published six days per week.[5] The first edition of the Providence Daily Journal appeared July 1, 1829.[6] In the next few decades the paper was sold to new owners several times, until by 1863 it was owned by George Danielson and Henry B. Anthony. The latter would go on to serve as Governor of Rhode Island and United States Senator.

Editor George W. Danielson joined the paper on January 1, 1863, and served as editor until his death in 1884. Danielson immediately launched an evening edition, called the Evening Bulletin. By July 1871, the Journal had grown large enough that it moved to larger quarters at the Barton Block.[6] During the Danielson and Anthony years, the paper was known for its strong support of the Republican Party, known by the nickname "The Republican Bible". After Danielson's death, the paper became less partisan, and by 1888 declared its political independence.[5]

In 1877, Danielson hired Charles Henry Dow, a young journalist with an interest in history. At the Journal, Dow developed a "news index" which summarized stories of historic interest.[7] It is possible this was an early inspiration for Dow's later development of his "stock index" at the Wall Street Journal.[7] While at the Journal Dow wrote a series on "The History of Steam Navigation between New York and Providence."[7] Dow also traveled to Colorado to report on the Colorado Silver Boom and the Leadville miners' strike; these stories were published in May and June 1879.[7] On the Colorado trip, Dow traveled with a team of Wall Street financiers and geologists, leading Dow to leave Providence for New York City in 1879 to advance his career as a reporter on mining stocks.[7]

In 1885, a Sunday edition was added, making the publication schedule seven days per week.

In 1872 the first diner in America, a horse-drawn wagon serving hot food, was founded to serve the employees of the Providence Journal.

The War Years

Before American entry into World War I, Journal publisher and Australian immigrant John R. Rathom attempted to stir up public sentiment in favor of the war against the Central Powers. He frequently published exposés of German subversive activities in the United States, claiming that the Journal had intercepted secret German communications. By 1920, it was revealed that Rathom's information was supplied by British intelligence agents.[8] Still, Rathom remained editor until his death in 1923.[5]

The Journal dropped "Daily" from its name and became The Providence Journal in 1920. In 1992, the Bulletin was discontinued and its name was appended onto that of the morning paper: The Providence Journal-Bulletin.

Starting in 1925, the Journal became the first in the country to expand coverage statewide.[5] It had news bureaus throughout Rhode Island and southeastern Massachusetts, a trend that had been inaugurated in 1925 by then-managing editor Sevellon Brown. Bureaus in Westerly, South Kingstown, Warwick, West Warwick, Greenville, Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Newport, Bristol/Warren, Attleboro and Fall River were designed to make sure that reporters were only 20 minutes away from breaking news.[9]

In 1937, the only competing Providence-based daily, the Star-Tribune, went bankrupt and was sold. The Providence Journal company bought it and kept it running for four months, then shut it down.[5]

The paper also had a variety of regional editions, which it called zones, that focused on city and town news. The system produced an intense focus on local news typically seen only in small-town newspapers. For example, everyone who died in the Journal's coverage area, rich or poor, received a free staff-written obituary.

Post-war Pulitzers

Chief editorial writer George W. Potter won the Journal's first Pulitzer in 1945 for a series of essays, and the entire editorial staff won in 1953 for local deadline reporting.[5]

Uncovering Nixon tax scandal

During the 1970s, reporter Jack White, then manager of the Providence Journal-Bulletin bureau in Newport, Rhode Island, cultivated sources among Newport's elite.[10] One source passed on to White evidence that President Richard Nixon had paid taxes amounting to $792.81 in 1970 and $878.03 in 1971, despite earning more than $400,000.[10] White discovered that Nixon had illegally back-dated the donation of his papers to the National Archives, in order to avoid a new law which made such donations ineligible for tax deductions.[10]

The night he was prepared to write the story, in September 1973, the union representing reporters at the newspaper voted to go on strike.[11] White would later recall rolling the story out of his typewriter, folding it up and putting it in his wallet.[11] He said he never thought about giving the story to management, even though he risked missing the story.[11] Twelve days later, the strike ended, and the story ran on October 3, 1973.[11]

At an Associated Press Managing Editors convention the following month, Journal reporter Joseph Ungaro asked Nixon about the story.[10] Nixon replied with a quote that was to become associated with him for the rest of his life: "People have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook."[10] Shortly after this, the I.R.S. audited Nixon's tax returns. By December 1973, Nixon, under pressure, released five years of tax documents.[10] This set a precedent for Presidents and presidential candidates to release tax returns, a custom that continued to 2016.[10] White's story forced Nixon to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in owed taxes. The story won White the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting.[10]

In 1988 the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSICOP) presented reporter C. Eugene Emery, Jr. with the Responsibility in Journalism Award for his researched claims of faith-healer Ralph A. DiOrio and wrote about the results in his journal.[12][13]

1990s

In the 1990s, rising production costs and declines in circulation prompted the Journal to consolidate both the bureaus and the editions. The editors tried to reinvigorate the coverage of city and town news in 1996, but competition from the Internet added fuel to the decline.

In 1997, the Livingston Award, sometimes called the "Pulitzer Prize for the Young,"[14][15] was awarded to Journal reporter C. J. Chivers for International Reporting for his series on the collapse of commercial fishing in the North Atlantic.[16] Chivers, aged 32[14] when he won the award, left the Journal in 1999[17] to go to the New York Times.[14]

Labor troubles

In 2001, reports in industry journals suggested that the Providence Journal was suffering from labor troubles, in which a "poisoned" workplace atmosphere led to a "talent hemorrhage."[18] At least 35 news staffers left the paper between January 2000 and summer 2001, including 16 reporters, seven desk editors, two managerial staffers, and 10 administrative staff members.[18] Publisher Howard Sutton denied there was a high turnover and called it normal attrition.[18]

In June 2001, Livingston Award-winning former Journal reporter C.J. Chivers added to the allegations when he wrote an open letter to Belo chairman Robert W. Decherd, critical of Belo's management.[17] In the letter he expressed concern that poor management was responsible for the departure of 57 employees.[17] He accused management of "assuming a counterproductive attitude toward its staff," which included fights over expenses, and over-reliance on freelancers and interns.[17]

Financial problems

In the face of declining revenue, the paper began charging for obituaries on January 4, 2005.

The paper's last Massachusetts edition was published on March 10, 2006. On Oct. 10, 2008 the paper stopped publishing all of its zoned editions in Rhode Island and laid off 33 news staffers, including three managers. Even during the Great Depression, the Journal had not terminated news staff to cut costs.

The next few years included an extensive campaign to make the Internet version of the paper profitable. The Journal aggressively marketed its news on the web, pushing to get detailed stories onto its website, projo.com, before competing radio, television and other print outlets. But circulation continued to decline and online advertising failed to compensate.

On Oct. 18, 2011 with circulation down to about 94,000 on weekdays and 129,000 on Sundays (down from 164,000 and over 231,000 in 2005),[19] the Journal renamed its website providencejournal.com, a move which meant that most of the previously Internet links to its content no longer worked. It also began implementing a system to require online readers to pay for content. Interactive images of its newspaper pages were initially available on personal computers and the iPad for free. The paywall was put in place on February 28, 2012. The new website was part of a larger rebranding project by Nail Communications which also included a campaign entitled "We Work For The Truth".[20] The rebranding failed to stem the circulation decline.

Throughout most of its history, the paper was privately owned. After the Journal became publicly traded and had acquired several television stations throughout the country, it was sold to the Dallas-based Belo Corp in 1996. Belo also owned several television stations. The company later split into two entities and one—A.H. Belo—took control of the newspapers.

On Dec. 4, 2013, A.H. Belo announced that it was seeking a buyer for the Journal, including its headquarters on 75 Fountain St. and its separate printing facility.[21] The company said it wanted to focus on business interests in Dallas. Workers were not surprised because the announcement came after the company sold one of its other papers, the Riverside Press-Enterprise in California.[22]

A.H. Belo announced on July 22, 2014 that it was selling the paper's assets to New Media Investment Group Inc., parent company of Fairport, N.Y.-based GateHouse Media, for $46 million. By then, the Journal's Monday through Friday circulation had dropped to 74,400, with an average of 99,100 on Sundays. Its website was getting 1.4 million unique users on an average month.[23] The sale was completed on Sept. 3, 2014, as several employees, including widely respected columnist Bob Kerr, were told they would not be transferred to the new company.

Bernie Szachara, senior vice president for publishing and group publisher at Local Media Group, a division of GateHouse Media, assumed the title of interim publisher, succeeding Howard G. Sutton.[24] On Feb. 27, 2015, Janet Hasson was named president and publisher of the Journal. (The GateHouse Media news release announcing the appointment [25] incorrectly reported that Hasson was the paper's first female publisher. That distinction belongs to Mary Caroline Knowles, who was publisher from 1874 until 1879.[26][27]) The paper reported the following October that its average daily paid circulation for the past year, including electronic copies, had dropped to 70,600[2] with 89,452 on Sundays.[3]

Headquarters

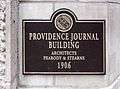

The paper in its early days changed headquarters as the paper grew.[28] In 1905 the paper announced its move from Eddy Street to a brand new building next door at the corner of Eddy and Westminster St.[28] The old building was demolished, and the new building extended over the site of the old.[28] The ornate new building was designed by the noted Boston architectural firm of Peabody and Stearns. The Journal moved in 1934 to its present building on Fountain Street.[28]

The Providence Journal building at 203 Westminster Street

The Providence Journal building at 203 Westminster Street Plaque on the old Providence Journal building

Plaque on the old Providence Journal building The current home of the Providence Journal on Fountain Street

The current home of the Providence Journal on Fountain Street

Journalism prizes and awards

- Chief editorial writer George W. Potter won the Journal's first Pulitzer in 1945 for a series of editorials on freedom of the press[29]

- In 1950, editor Sevellon Brown and reporter Ben Bagdikian received Honorable Mention from the Peabody Awards for a series of commentaries and criticisms of broadcasts by Walter Winchell[30]

- In 1953 the editorial staff won the Pulitzer for local reporting their spontaneous and cooperative coverage of a bank robbery and police chase leading to the capture of the bandit.[31]

- In 1974, reporter Jack White won a Pulitzer Prize in National Reporting for investigating President Richard Nixon's Federal income tax payments in 1970 and 1971.[32]

- In 1994, the Journal won a Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting for exposing corruption in the Rhode Island court system[33]

- In 1997, the Livingston Award, sometimes called the "Pulitzer Prize for the Young,"[14][15] was awarded to Journal reporter C. J. Chivers for International Reporting for his series on the collapse of commercial fishing in the North Atlantic.[16]

- In 2016, the Journal was named New England Newspaper of the Year by the New England Newspaper and Press Association. The Journal also received the top editorial writing and public service awards.[34]

Prices

The Providence Journal is sold for $2 daily since the spring of 2015. It is $3.50 Sundays & Thanksgiving Day.

Volume numbering

Through the paper's long history, there were some inconsistencies in its volume numbering. In 1972, when the when the Saturday editions of the Journal and Bulletin were combined to create the Journal-Bulletin, the Saturday edition was reset to become Volume 1, Number 1.[1] The daily edition of of the paper followed suit in 1995 (becoming Volume XXIII) upon the termination of the Evening Bulletin.[1] In July 2017, the Journal announced it was resorting back to the original volume numbering. The Friday, July 21 edition of the newspaper was set to become Vol. CLXXXIX, No. 1, to mark the first paper of the 189th year.[1]

In popular culture

- In the television series Gilmore Girls, Rory Gilmore has a job interview at the newspaper.

- In the Farrelly brothers film Hall Pass, Owen Wilson's character Rick can be seen reading a copy of the newspaper in one scene.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rosenberg, Alan (16 July 2017). "The Providence Journal’s 188th-birthday mystery". Providence, Rhode Island: The Providence Journal. p. A2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- 1 2 The Providence Journal, "Statement of Ownership, Management and Circulation, Oct. 6, 2015, page B7

- 1 2 The Providence Sunday Journal, "Statement of Ownership, Management and Circulation, Oct. 11, 2015, page E5

- ↑ "Digital Extra: The Journal's 175th Anniversary - For the record". The Providence Journal Co. 2004-07-21. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Providence Journal Company - Company Profile, Information, Business Description, History, Background Information on The Providence Journal Company". Reference for Business. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- 1 2 Greene, Welcome Arnold (1886). The Providence Plantations for 250 Years. Providence, RI: J.A. & R.A. Reid, Publishers and Printers. pp. 318–319.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Charles Henry Dow". American National Biography Online. American National Biography. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ Arsenault, Mark (21 July 2004). "WWI 100 Years: Journal editor Rathom lied about personal, paper's role in exposing German spies". Providence Journal. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "The Providence Journal Company". FundingUniverse.com, Company Histories & Profiles. n.d. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Zuckoff, Mitchell (5 August 2016). "Why We Ask to See Candidates’ Tax Returns". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Obituary: Jack White, 63". Cape Cod Times. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ "Articles of Note". The Skeptical Inquirer. 13 (4): 425. 1988.

- ↑ Shore, Lys Ann (1988). "New Light on the New Age CSICOP's Chicago conference was the first to critically evaluate the New Age movement.". The Skeptical Inquirer. 13 (3): 226–235.

- 1 2 3 4 Eisendrath, Charles R. (11 June 2014). "New Livingston Awards Winners to the Fast Track". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Livingston Awards, "Pulitzer of the Young," adds digital nominators, expands outreach and seeks endowment with new funding". Knight Foundation. John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 "Library: Empty Nets: Atlantic Banks in Peril (series)". University of Michigan. Wallace House. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "New York Times reporter cites poor morale at Providence Journal". Guild Leader. XII (35). 3 July 2001. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 Wenner, Kathryn (July–August 2001). "You Say Hemorrhage, I Say Attrition". American Journalism Review (July–August 2001). Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ "Projo hit by 61% drop in advertising since '05; digital declining". WPRI.com. 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2012-03-24.

- ↑ Providence Journal Commercial - "Truth"

- ↑ "A.H. Belo Hires Arkansas Firm to Explore Sale of the Providence Journal". Rhode Island Public Radio. 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ↑ "Scott MacKay Commentary: Providence Journal, We Knew Ye Well". Rhode Island Public Radio. 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ↑ "Longtime Journal publisher Sutton to retire; interim publisher named". ProvidenceJournal.com. 2014-08-29. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ↑ "New Media completes purchase of The Providence Journal". ProvidenceJournal.com. 2014-09-03. Retrieved 2014-09-03.

- ↑ "Accomplished media executive becomes first female publisher of The Providence Journal". gatehousemedia.com. 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ↑ "Journal names new top editor". ahbelo.com. 2014-04-14. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ↑ "Janet Hasson, Gannett veteran, named president, publisher of The Providence Journal". ProvidenceJournal.com. 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Delaney, Michael (16 July 2017). "Time Lapse: Read all about it". Providence, Rhode Island: The Providence Journal. p. F2. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ "1945 Pulitzer Prizes". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ "Providence Journal, Its Editor and Publisher, Sevellon Brown, and Ben Bagdikian, Reporter for the Series of Articles Analyzing the Broadcasts of Top Commentators". Peabody: Stories that Matter. The Peabody Awards. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ "1953 Pulitzer Prizes". The Pulitzer Prize. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ "1974 Pulitzer Prizes". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ "1994 Pulitzer Prizes". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ Journal Staff (6 October 2016). "Providence Journal named best in N.E.". The Providence Journal. Retrieved 7 October 2016.