Earthing system

| Relevant topics on |

| Electrical Installations |

|---|

| Wiring practice by region or country |

| Regulation of electrical installations |

| Cabling and accessories |

| Switching and protection devices |

In an electrical installation or an electricity supply system an earthing system or grounding system connects specific parts of that installation with the Earth's conductive surface for safety and functional purposes. The point of reference is the Earth's conductive surface, or on ships, the surface of the sea. The choice of earthing system can affect the safety and electromagnetic compatibility of the installation. Regulations for earthing systems vary considerably among countries and among different parts of electrical systems, though many follow the recommendations of the International Electrotechnical Commission which are described below.

This article only concerns grounding for electrical power. Examples of other earthing systems are listed below with links to articles:

- To protect a structure from lightning strike, directing the lightning through the earthing system and into the ground rod rather than passing through the structure.

- As part of a single-wire earth return power and signal lines, such as were used for low wattage power delivery and for telegraph lines.

- In radio, as a ground plane for large monopole antenna.

- As ancillary voltage balance for other kinds of radio antennas, such as dipoles.

- As the feed-point of a ground dipole antenna for VLF and ELF radio.

Objectives of electrical earthing

Protective earthing

In the UK "Earthing" is the connection of the exposed-conductive parts of the installation by means of protective conductors to the "main earthing terminal", which is connected to an electrode in contact with the earth's surface.[1] A protective conductor (PE)[1] (known as an equipment grounding conductor in the US National Electrical Code) avoids electric shock hazard by keeping the exposed-conductive surface of connected devices close to earth potential in fault conditions. In the event of a fault, a current is allowed to flow to earth by the earthing system. If this is excessive the overcurrent protection of a fuse or circuit breaker will operate, thereby protecting the circuit and removing any fault-induced voltages from the exposed-conductive surfaces. This disconnection is a fundamental tenet of modern wiring practice and is referred to as the "Automatic Disconnection of Supply" (ADS). Maximum allowable earth fault loop impedance values and the characteristics of overcurrent protection devices are strictly specified in electrical safety regulations to ensure this happens promptly and that whilst overcurrent is flowing hazardous voltages do not occur on the conductive surfaces.[2] Protection is therefore by limiting the elevation of voltage and its duration.

The alternative is defense in depth – such as reinforced or double insulation – where multiple independent failures must occur to expose a dangerous condition.

Functional earthing

A functional earth connection serves a purpose other than electrical safety, and may carry current as part of normal operation.[1] The most important example of a functional earth is the neutral in an electrical supply system when it is a current-carrying conductor connected to the earth electrode at the source of electrical power. Other examples of devices that use functional earth connections include surge suppressors and electromagnetic interference filters.

Low-voltage systems

In low-voltage distribution networks, which distribute the electric power to the widest class of end users, the main concern for design of earthing systems is safety of consumers who use the electric appliances and their protection against electric shocks. The earthing system, in combination with protective devices such as fuses and residual current devices, must ultimately ensure that a person must not come into touch with a metallic object whose potential relative to the person's potential exceeds a "safe" threshold, typically set at about 50 V.

On electricity networks with a system voltage of 240 V to 1.1 kV, which are mostly used in industrial / mining equipment / machines rather than publicly accessible networks, the earthing system design is as equally important from safety point of view as for domestic users.

In most developed countries, 220 V, 230 V, or 240 V sockets with earthed contacts were introduced either just before or soon after World War II, though with considerable national variation in popularity. In the United States and Canada, 120 V power outlets installed before the mid-1960s generally did not include a ground (earth) pin. In the developing world, local wiring practice may not provide a connection to an earthing pin of an outlet.

For a time, US National Electrical Code allowed certain major appliances permanently connected to the supply to use the supply neutral wire as the equipment enclosure connection to ground. This was not permitted for plug-in equipment as the neutral and energized conductor could easily be accidentally exchanged, creating a severe hazard. If the neutral was interrupted, the equipment enclosure would no longer be connected to ground. Normal imbalances in a split phase distribution system could create objectionable neutral to ground voltages. Recent editions of the NEC no longer permit this practice. For these reasons, most countries have now mandated dedicated protective earth connections that are now almost universal.

If the fault path between accidentally energized objects and the supply connection has low impedance, the fault current will be so large that the circuit overcurrent protection device (fuse or circuit breaker) will open to clear the ground fault. Where the earthing system does not provide a low-impedance metallic conductor between equipment enclosures and supply return (such as in a TT separately earthed system), fault currents are smaller, and will not necessarily operate the overcurrent protection device. In such case a residual current detector is installed to detect the current leaking to ground and interrupt the circuit.

IEC terminology

International standard IEC 60364 distinguishes three families of earthing arrangements, using the two-letter codes TN, TT, and IT.

The first letter indicates the connection between earth and the power-supply equipment (generator or transformer):

- "T" — Direct connection of a point with earth (Latin: terra)

- "I" — No point is connected with earth (isolation), except perhaps via a high impedance.

The second letter indicates the connection between earth or network and the electrical device being supplied:

- "T" — Earth connection is by a local direct connection to earth (Latin: terra), usually via a ground rod.

- "N" — Earth connection is supplied by the electricity supply Network, either as a separate protective earth (PE) conductor or combined with the neutral conductor.

Types of TN networks

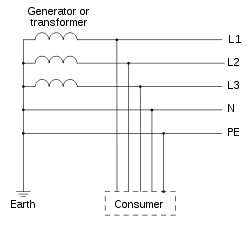

In a TN earthing system, one of the points in the generator or transformer is connected with earth, usually the star point in a three-phase system. The body of the electrical device is connected with earth via this earth connection at the transformer. This arrangement is a current standard for residential and industrial electric systems particularly in Europe.[3]

The conductor that connects the exposed metallic parts of the consumer's electrical installation is called protective earth (PE; see also: Ground). The conductor that connects to the star point in a three-phase system, or that carries the return current in a single-phase system, is called neutral (N). Three variants of TN systems are distinguished:

- TN−S

- PE and N are separate conductors that are connected together only near the power source.

- TN−C

- A combined PEN conductor fulfils the functions of both a PE and an N conductor. (on 230/400v systems normally only used for distribution networks)

- TN−C−S

- Part of the system uses a combined PEN conductor, which is at some point split up into separate PE and N lines. The combined PEN conductor typically occurs between the substation and the entry point into the building, and earth and neutral are separated in the service head. In the UK, this system is also known as protective multiple earthing (PME), because of the practice of connecting the combined neutral-and-earth conductor to real earth at many locations, to reduce the risk of electric shock in the event of a broken PEN conductor. Similar systems in Australia and New Zealand are designated as multiple earthed neutral (MEN) and, in North America, as multi-grounded neutral (MGN).

|

|

|

| TN-S: separate protective earth (PE) and neutral (N) conductors from transformer to consuming device, which are not connected together at any point after the building distribution point. | TN-C: combined PE and N conductor all the way from the transformer to the consuming device. | TN-C-S earthing system: combined PEN conductor from transformer to building distribution point, but separate PE and N conductors in fixed indoor wiring and flexible power cords. |

It is possible to have both TN-S and TN-C-S supplies taken from the same transformer. For example, the sheaths on some underground cables corrode and stop providing good earth connections, and so homes where high resistance "bad earths" are found may be converted to TN-C-S. This is only possible on a network when the neutral is suitably robust against failure, and conversion is not always possible. The PEN must be suitable reinforced against failure, as an open circuit PEN can impress full phase voltage on any exposed metal connected to the system earth downstream of the break. The alternative is to provide a local earth and convert to TT. The main attraction of a TN network is the low impedance earth path allows easy automatic disconnection (ADS) on a high current circuit in the case of a line-to-PE short circuit as the same breaker or fuse will operate for either L-N or L-PE faults, and an RCD is not needed to detect earth faults.

TT network

In a TT (Terra-Terra) earthing system, the protective earth connection for the consumer is provided by a local earth electrode, (sometimes referred to as the Terra-Firma connection) and there is another independently installed at the generator. There is no 'earth wire' between the two. The fault loop impedance is higher, and unless the electrode impedance is very low indeed, a TT installation should always have an RCD (GFCI) as its first isolator.

The big advantage of the TT earthing system is the reduced conducted interference from other users' connected equipment. TT has always been preferable for special applications like telecommunication sites that benefit from the interference-free earthing. Also, TT networks do not pose any serious risks in the case of a broken neutral. In addition, in locations where power is distributed overhead, earth conductors are not at risk of becoming live should any overhead distribution conductor be fractured by, say, a fallen tree or branch.

In pre-RCD era, the TT earthing system was unattractive for general use because of the difficulty of arranging reliable automatic disconnection (ADS) in the case of a line-to-PE short circuit (in comparison with TN systems, where the same breaker or fuse will operate for either L-N or L-PE faults). But as residual current devices mitigate this disadvantage, the TT earthing system has become much more attractive providing that all AC power circuits are RCD-protected. In some countries (such as the UK) is recommended for situations where an low impedance equipotential zone is impractical to maintain by bonding, where there is significant outdoor wiring, such as supplies to mobile homes and some agricultural settings, or where a high fault current could pose other dangers, such as at fuel depots or marinas.

The TT earthing system is used throughout Japan, with RCD units in most industrial settings. This can impose added requirements on variable frequency drives and switched-mode power supplies which often have substantial filters passing high frequency noise to the ground conductor.

IT network

In an IT network, the electrical distribution system has no connection to earth at all, or it has only a high impedance connection.

Comparison

| TT | IT | TN-S | TN-C | TN-C-S | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth fault loop impedance | High | Highest | Low | Low | Low |

| RCD preferred? | Yes | N/A | Optional | No | Optional |

| Need earth electrode at site? | Yes | Yes | No | No | Optional |

| PE conductor cost | Low | Low | Highest | Least | High |

| Risk of broken neutral | No | No | High | Highest | High |

| Safety | Safe | Less Safe | Safest | Least Safe | Safe |

| Electromagnetic interference | Least | Least | Low | High | Low |

| Safety risks | High loop impedance (step voltages) | Double fault, overvoltage | Broken neutral | Broken neutral | Broken neutral |

| Advantages | Safe and reliable | Continuity of operation, cost | Safest | Cost | Safety and cost |

Other terminologies

While the national wiring regulations for buildings of many countries follow the IEC 60364 terminology, in North America (United States and Canada), the term "equipment grounding conductor" refers to equipment grounds and ground wires on branch circuits, and "grounding electrode conductor" is used for conductors bonding an earth ground rod (or similar) to a service panel. "Grounded conductor" is the system "neutral". Australian and New Zealand standards use a modified PME earthing system called Multiple Earthed Neutral (MEN). The neutral is grounded(earthed) at each consumer service point thereby effectively bringing the neutral potential difference to zero along the whole length of LV lines. In the UK and some Commonwealth countries, the term "PNE", meaning Phase-Neutral-Earth is used to indicate that three (or more for non-single-phase connections) conductors are used, i.e., PN-S.

Resistance-earthed neutral (India)[4]

Similar to HT system, resistance earth system is also introduced for mining in India as per Central Electricity Authority Regulations for LT system (1100 V > LT > 230 V). In place of solid earthing of star neutral point a suitable neutral grounding resistance (NGR) is added in between, restricting the earth leakage current up to 750 mA. Due to the fault current restriction it is more safe for gassy mines.

As earth leakage is restricted, leakage protection has highest limit for input of 750 mA only. In solid earthed system leakage current can go up to short circuit current, here it is restricted to maximum 750 mA. This restricted operating current reduce overall operating efficiency of leakage relay protection. Importance of efficient and most reliable protection has increased for safety, against electric shock in mines.

In this system there are possibilities that the resistance connected get open. To avoid this additional protection to monitor the resistance is deployed, which disconnect power in case of the fault.[5]

Earth leakage protection

Earth Leakage of current can be very harmful for human beings, should it pass through them. To avoid accidental shock by electrical appliances/ equipment earth leakage relay/sensor are utilized at the source to isolate the power when leakage exceed certain limit. Earth leakage circuit breaker are used for the purpose. Current sensing breaker are called RCB/ RCCB. In the industrial applications, Earth leakage relays are used with separate CT(current transformer) called CBCT(core balanced current transformer) which sense leakage current(zero phase sequence current) of the system through the secondary of the CBCT and this operates the relay.[6] This protection works in the range of milli-Amps and can be set from 30 mA to 3000 mA.

Earth connectivity check

A separate pilot core p is run from distribution/ equipment supply system in addition to earth core. Earth connectivity check device is fixed at the sourcing end which continuously monitor earth connectivity. The pilot core p initiate from this check device and runs through connecting trailing cable which generally supply power to moving mining machinery(LHD). This core p is connected to earth at the distribution end through a diode circuit, which complete the electric circuit initiated from the check device.[7]When earth connectivity to vehicle is broken, this pilot core circuit get disconnected, the protecting device fixed at sourcing end activate and, isolate the power to machine. This type of circuit is a must for portable heavy electric equipment (like LHD (Load, Haul, Dump machine)) being used in under ground mines.

Properties

Cost

- TN networks save the cost of a low-impedance earth connection at the site of each consumer. Such a connection (a buried metal structure) is required to provide protective earth in IT and TT systems.

- TN-C networks save the cost of an additional conductor needed for separate N and PE connections. However, to mitigate the risk of broken neutrals, special cable types and lots of connections to earth are needed.

- TT networks require proper RCD (Ground fault interrupter) protection.

Safety

- In TN, an insulation fault is very likely to lead to a high short-circuit current that will trigger an overcurrent circuit-breaker or fuse and disconnect the L conductors. With TT systems, the earth fault loop impedance can be too high to do this, or too high to do it within the required time, so an RCD (formerly ELCB) is usually employed. Earlier TT installations may lack this important safety feature, allowing the CPC (Circuit Protective Conductor or PE) and perhaps associated metallic parts within reach of persons (exposed-conductive-parts and extraneous-conductive-parts) to become energized for extended periods under fault conditions, which is a real danger.

- In TN-S and TT systems (and in TN-C-S beyond the point of the split), a residual-current device can be used for additional protection. In the absence of any insulation fault in the consumer device, the equation IL1+IL2+IL3+IN = 0 holds, and an RCD can disconnect the supply as soon as this sum reaches a threshold (typically 10 mA – 500 mA). An insulation fault between either L or N and PE will trigger an RCD with high probability.

- In IT and TN-C networks, residual current devices are far less likely to detect an insulation fault. In a TN-C system, they would also be very vulnerable to unwanted triggering from contact between earth conductors of circuits on different RCDs or with real ground, thus making their use impracticable. Also, RCDs usually isolate the neutral core. Since it is unsafe to do this in a TN-C system, RCDs on TN-C should be wired to only interrupt the line conductor.

- In single-ended single-phase systems where the Earth and neutral are combined (TN-C, and the part of TN-C-S systems which uses a combined neutral and earth core), if there is a contact problem in the PEN conductor, then all parts of the earthing system beyond the break will rise to the potential of the L conductor. In an unbalanced multi-phase system, the potential of the earthing system will move towards that of the most loaded line conductor. Such a rise in the potential of the neutral beyond the break is known as a neutral inversion.[8] Therefore, TN-C connections must not go across plug/socket connections or flexible cables, where there is a higher probability of contact problems than with fixed wiring. There is also a risk if a cable is damaged, which can be mitigated by the use of concentric cable construction and multiple earth electrodes. Due to the (small) risks of the lost neutral raising 'earthed' metal work to a dangerous potential, coupled with the increased shock risk from proximity to good contact with true earth, the use of TN-C-S supplies is banned in the UK for caravan sites and shore supply to boats, and strongly discouraged for use on farms and outdoor building sites, and in such cases it is recommended to make all outdoor wiring TT with RCD and a separate earth electrode.

- In IT systems, a single insulation fault is unlikely to cause dangerous currents to flow through a human body in contact with earth, because no low-impedance circuit exists for such a current to flow. However, a first insulation fault can effectively turn an IT system into a TN system, and then a second insulation fault can lead to dangerous body currents. Worse, in a multi-phase system, if one of the line conductors made contact with earth, it would cause the other phase cores to rise to the phase-phase voltage relative to earth rather than the phase-neutral voltage. IT systems also experience larger transient overvoltages than other systems.

- In TN-C and TN-C-S systems, any connection between the combined neutral-and-earth core and the body of the earth could end up carrying significant current under normal conditions, and could carry even more under a broken neutral situation. Therefore, main equipotential bonding conductors must be sized with this in mind; use of TN-C-S is inadvisable in situations such as petrol stations, where there is a combination of lots of buried metalwork and explosive gases.

Electromagnetic compatibility

- In TN-S and TT systems, the consumer has a low-noise connection to earth, which does not suffer from the voltage that appears on the N conductor as a result of the return currents and the impedance of that conductor. This is of particular importance with some types of telecommunication and measurement equipment.

- In TT systems, each consumer has its own connection to earth, and will not notice any currents that may be caused by other consumers on a shared PE line.

Regulations

- In the United States National Electrical Code and Canadian Electrical Code the feed from the distribution transformer uses a combined neutral and grounding conductor, but within the structure separate neutral and protective earth conductors are used (TN-C-S). The neutral must be connected to earth only on the supply side of the customer's disconnecting switch.

- In Argentina, France (TT) and Australia (TN-C-S), the customers must provide their own ground connections.

- Japan is governed by PSE law, and uses TT earthing in most installations.

- In Australia, the Multiple Earthed Neutral (MEN) earthing system is used and is described in Section 5 of AS 3000. For an LV customer, it is a TN-C system from the transformer in the street to the premises, (the neutral is earthed multiple times along this segment), and a TN-S system inside the installation, from the Main Switchboard downwards. Looked at as a whole, it is a TN-C-S system.

- In Denmark the high voltage regulation (Stærkstrømsbekendtgørelsen) and Malaysia the Electricity Ordinance 1994 states that all consumers must use TT earthing, though in rare cases TN-C-S may be allowed (used in the same manner as in the United States). Rules are different when it comes to larger companies.

- In India as per Central Electricity Authority Regulations, CEAR, 2010, rule 41, there is provision of earthing, neutral wire of a 3-phase, 4-wire system and the additional third wire of a 2- phase, 3-wire system. Earthing is to be done with two separate connections. Grounding system also to have minimum two or more earth pits (electrode) such that proper grounding takes place. As per the rule 42, installation with load above 5 kW exceeding 250 V shall have suitable Earth leakage protective device to isolate the load in case of earth fault or leakage.[9]

Application examples

- In the areas of UK where underground power cabling is prevalent, the TN-S system is common.[10]

- In India LT supply is generally through TN-S system. Neutral is double grounded at distribution transformer. Neutral and earth run separately on distribution overhead line/cables. Separate conductor for overhead lines and armoring of cables are used for earth connection. Additional earth electrodes/pits are installed at user ends for strengthening earth.[11]

- Most modern homes in Europe have a TN-C-S earthing system. The combined neutral and earth occurs between the nearest transformer substation and the service cut out (the fuse before the meter). After this, separate earth and neutral cores are used in all the internal wiring.

- Older urban and suburban homes in the UK tend to have TN-S supplies, with the earth connection delivered through the lead sheath of the underground lead-and-paper cable.

- Older homes in Norway uses the IT system while newer homes use TN-C-S.

- Some older homes, especially those built before the invention of residual-current circuit breakers and wired home area networks, use an in-house TN-C arrangement. This is no longer recommended practice.

- Laboratory rooms, medical facilities, construction sites, repair workshops, mobile electrical installations, and other environments that are supplied via engine-generators where there is an increased risk of insulation faults, often use an IT earthing arrangement supplied from isolation transformers. To mitigate the two-fault issues with IT systems, the isolation transformers should supply only a small number of loads each and should be protected with an insulation monitoring device (generally used only by medical, railway or military IT systems, because of cost).

- In remote areas, where the cost of an additional PE conductor outweighs the cost of a local earth connection, TT networks are commonly used in some countries, especially in older properties or in rural areas, where safety might otherwise be threatened by the fracture of an overhead PE conductor by, say, a fallen tree branch. TT supplies to individual properties are also seen in mostly TN-C-S systems where an individual property is considered unsuitable for TN-C-S supply.

- In Australia, New Zealand and Israel the TN-C-S system is in use; however, the wiring rules currently state that, in addition, each customer must provide a separate connection to earth via both a water pipe bond (if metallic water pipes enter the consumer's premises) and a dedicated earth electrode. In Australia and New Zealand this is called the Multiple Earthed Neutral Link or MEN Link. This MEN Link is removable for installation testing purposes, but is connected during use by either a locking system (locknuts for instance) or two or more screws. In the MEN system, the integrity of the Neutral is paramount. In Australia, new installations must also bond the foundation concrete re-enforcing under wet areas to the earth conductor (AS3000), typically increasing the size of the earthing, and provides an equipotential plane in areas such as bathrooms. In older installations, it is not uncommon to find only the water pipe bond, and it is allowed to remain as such, but the additional earth electrode must be installed if any upgrade work is done. The protective earth and neutral conductors are combined until the consumer's neutral link (located on the customer's side of the electricity meter's neutral connection) – beyond this point, the protective earth and neutral conductors are separate.

High-voltage systems

In high-voltage networks (above 1 kV), which are far less accessible to the general public, the focus of earthing system design is less on safety and more on reliability of supply, reliability of protection, and impact on the equipment in presence of a short circuit. Only the magnitude of phase-to-ground short circuits, which are the most common, is significantly affected with the choice of earthing system, as the current path is mostly closed through the earth. Three-phase HV/MV power transformers, located in distribution substations, are the most common source of supply for distribution networks, and type of grounding of their neutral determines the earthing system.

There are five types of neutral earthing:[12]

- Solid-earthed neutral

- Unearthed neutral

- Resistance-earthed neutral

- Low-resistance earthing

- High-resistance earthing

- Reactance-earthed neutral

- Using earthing transformers (such as the Zigzag transformer)

Solid-earthed neutral

In solid or directly earthed neutral, transformer's star point is directly connected to the ground. In this solution, a low-impedance path is provided for the ground fault current to close and, as result, their magnitudes are comparable with three-phase fault currents.[12] Since the neutral remains at the potential close to the ground, voltages in unaffected phases remain at levels similar to the pre-fault ones; for that reason, this system is regularly used in high-voltage transmission networks, where insulation costs are high.[13]

Resistance-earthed neutral

To limit short circuit earth fault additional neutral grounding resistance (NGR) is added between neutral, transformer's star point and the ground.

Low-resistance earthing

With low resistance fault current limit is relatively high. In India it is restricted for 50 A for open cast mines as per Central Electricity Authority Regulations, CEAR, 2010, rule 100.

Unearthed neutral

In unearthed, isolated or floating neutral system, as in the IT system, there is no direct connection of the star point (or any other point in the network) and the ground. As a result, ground fault currents have no path to be closed and thus have negligible magnitudes. However, in practice, the fault current will not be equal to zero: conductors in the circuit — particularly underground cables — have an inherent capacitance towards the earth, which provides a path of relatively high impedance.[14]

Systems with isolated neutral may continue operation and provide uninterrupted supply even in presence of a ground fault.[12] However, while the fault is present, the potential of other two phases relative to the ground reaches of the normal operating voltage, creating additional stress for the insulation; insulation failures may inflict additional ground faults in the system, now with much higher currents.[13]

Presence of uninterrupted ground fault may pose a significant safety risk: if the current exceeds 4 A – 5 A an electric arc develops, which may be sustained even after the fault is cleared.[14] For that reason, they are chiefly limited to underground and submarine networks, and industrial applications, where the reliability need is high and probability of human contact relatively low. In urban distribution networks with multiple underground feeders, the capacitive current may reach several tens of amperes, posing significant risk for the equipment.

The benefit of low fault current and continued system operation thereafter is offset by inherent drawback that the fault location is hard to detect.[15]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 BS7671:2008. Part 2 – definitions.

- ↑ BS7671:2008. Section 411 – Protective measure: automatic disconnection of supply.

- ↑ Cahier Technique Merlin Gerin n° 173 / p.9|http://www.schneider-electric.com/en/download/document/ECT173/

- ↑ ; Central Electricity Authority-(Measures relating to Safety and Electric Supply). Regulations, 2010; earthing system, rule 99 and protective devices, rule 100.

- ↑ , The Importance of the Neutral-Grounding Resistor

- ↑ ; Electrical Notes, Volume 1, By Sir Arthur Schuster, p.317

- ↑ Laughton, M A; Say, M G (2013). Electrical Engineer's Reference Book. Elsevier. p. 32. ISBN 9781483102634.

- ↑ Gates, B.G. (1936). Neutral inversion in power systems. In Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers 78 (471): 317–325. Retrieved 2012-03-20.

- ↑ ; Central Electricity Authority-(Measures relating to Safety and Electric Supply). Regulations, 2010; rule 41 and 42

- ↑ Trevor Linsley (2011). Basic Electrical Installation Work. Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-136-42748-0.

- ↑ "Indian Standard 3043 Code of Practice for Earthing" (PDF). Bureau of Indian Standards. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 Parmar, Jignesh, Types of neutral earthing in power distribution (part 1), EEP – Electrical Engineering Portal

- 1 2 Guldbrand, Anna (2006), System earthing (PDF), Industrial Electrical Engineering and Automation, Lund University

- 1 2 Bandyopadhyay, M. N. (2006). "21. Neutral earthing". Electrical Power Systems: Theory and Practice. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. pp. 488–491.

- ↑ Fischer, Normann; Hou, Daqing (2006), Methods for detecting ground faults in medium-voltage distribution power systems, Schweitzer Engineering Laboratories, Inc., p. 15

- General

- IEC 60364-1: Electrical installations of buildings — Part 1: Fundamental principles, assessment of general characteristics, definitions. International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva.

- John Whitfield: The Electricians Guide to the 16th Edition IEE Regulations, Section 5.2: Earthing systems, 5th edition.

- Geoff Cronshaw: Earthing: Your questions answered. IEE Wiring Matters, Autumn 2005.

- EU Leonardo ENERGY earthing systems education center: Earthing systems resources