Prostitution by country

This is a list of countries by prostitution statistics.

Africa

Prostitution is illegal in the majority of African countries. HIV/AIDS infection rates are particularly high among African sex workers.[1]

Nevertheless, it is common, driven by the widespread poverty in many sub-Saharan African countries,[2] and is one of the drivers for the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in Africa.[3] Social breakdown and poverty caused by civil war in several African countries has caused further increases in the rate of prostitution in those countries. For these reasons, some African countries have also become destinations for sex tourism.

Long distance truck drivers have been identified as a group with the high-risk behaviour of sleeping with prostitutes and a tendency to spread the infection along trade routes in the region. Infection rates of up to 33% were observed in this group in the late 1980s in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania.

In Gambia, prostitution is illegal. The majority of female sex workers are foreigners.

- Prostitution in Angola

- Prostitution in Botswana

- Prostitution in Burkina Faso

- Prostitution in the Central African Republic

- Prostitution in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Prostitution in Egypt

- Prostitution in Eritrea

- Prostitution in Guinea-Bissau

- Prostitution in Ivory Coast

- Prostitution in Kenya

- Prostitution in Libya

- Prostitution in Madagascar

- Prostitution in Malawi

- Prostitution in Mozambique

- Prostitution in Namibia

- Prostitution in Niger

- Prostitution in the Maldives

- Prostitution in Rwanda

- Prostitution in Somalia

- Prostitution in South Africa

- Prostitution in South Sudan

- Prostitution in Swaziland

- Prostitution in Tanzania

- Prostitution in Togo

- Prostitution in Tunisia

- Prostitution in Uganda

- Prostitution in Zimbabwe

Asia

In Asia, the main characteristic of the region is the very big discrepancy between the laws which exist on the books and what occurs in practice. For example, in Thailand prostitution is illegal,[4] but in practice it is tolerated and partly regulated, and the country is a destination for sex tourism. Such situations are common in many Asian countries.

In Japan, prostitution is legal[5] with the exception of heterosexual, vaginal intercourse. Advertisements that detail what each individual prostitute will do (oral sex, anal sex, etc.) are a common sight in the country, although many prostitutes disregard the law.

Child prostitution is a serious problem in this region. Past surveys indicate that 30 to 35 percent of all prostitutes in the Mekong sub-region of Southeast Asia are between 12 and 17 years of age.[6]

- Prostitution in Afghanistan

- Prostitution in Bahrain

- Prostitution in Bangladesh

- Prostitution in Bhutan

- Prostitution in Brunei

- Prostitution in Cambodia

- Prostitution in China

- Prostitution in East Timor

- Prostitution in India

- Prostitution in Indonesia

- Prostitution in Iran

- Prostitution in Iraq

- Prostitution in Israel

- Prostitution in Japan

- Prostitution in Kuwait

- Prostitution in Kyrgyzstan

- Prostitution in Laos

- Prostitution in Lebanon

- Prostitution in Malaysia

- Prostitution in Mongolia

- Prostitution in Myanmar

- Prostitution in Nepal

- Prostitution in North Korea

- Prostitution in Oman

- Prostitution in Pakistan

- Prostitution in the Palestinian territories

- Prostitution in the Philippines

- Prostitution in Qatar

- Prostitution in Russia

- Prostitution in Saudi Arabia

- Prostitution in Singapore

- Prostitution in South Korea

- Prostitution in Sri Lanka

- Prostitution in Syria

- Prostitution in Taiwan

- Prostitution in Tajikistan

- Prostitution in Thailand

- Prostitution in Turkmenistan

- Prostitution in Turkey

- Prostitution in the United Arab Emirates

- Prostitution in Uzbekistan

- Prostitution in Vietnam

- Prostitution in Yemen

Europe

The most common legal system in the European Union is that which allows prostitution itself (the exchange of sex for money) but prohibits associated activities (brothels, pimping, etc.). Prostitution remains illegal in most of the ex-communist countries of Eastern Europe. In recent years, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Northern Ireland and France have brought in laws making it illegal to pay for sex.

In Sweden, Northern Ireland, Norway, Iceland, Canada, France it is illegal to pay for sex (the client commits a crime, but not the prostitute).

In the United Kingdom, it is illegal to pay for sex with a prostitute who has been "subjected to force" and this is a strict liability offence (clients can be prosecuted even if they did not know the prostitute was forced), but prostitution itself is legal.[7][8]

In Germany prostitution is legal, as are brothels.

The enforcement of the anti-prostitution laws varies by country. One example is Belgium, in which brothels are illegal, but in practice, they are tolerated, operate quite openly, and in some parts of the country, the situation is similar of that in neighboring Netherlands.

In Eastern Europe, prostitution was outlawed by the former communist regimes, and most of those countries chose to keep it illegal even after the fall of the Communists. In Hungary and Latvia however, prostitution is legal and regulated.

- Prostitution in Armenia

- Prostitution in Austria

- Prostitution in the Czech Republic

- Prostitution in Denmark

- Prostitution in Estonia

- Prostitution in Finland

- Prostitution in France

- Prostitution in Germany

- Prostitution in Hungary

- Prostitution in Iceland

- Prostitution in Italy

- Prostitution in Latvia

- Prostitution in Monaco

- Prostitution in the Netherlands

- Prostitution in Northern Ireland

- Prostitution in Norway

- Prostitution in Poland

- Prostitution in Portugal

- Prostitution in the Republic of Ireland

- Prostitution in Russia

- Prostitution in Spain

- Prostitution in Sweden

- Prostitution in Switzerland

- Prostitution in Turkey

- Prostitution in the United Kingdom

- Prostitution in Ukraine

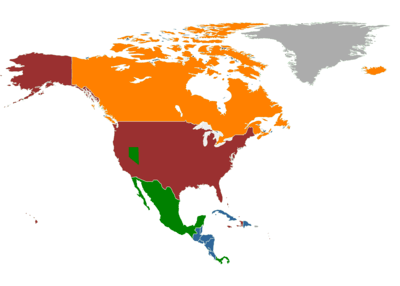

North America

- Prostitution in the United States

- Prostitution in Canada

- Prostitution in Costa Rica

- Prostitution in Cuba

- Prostitution in the Dominican Republic

- Prostitution in El Salvador

- Prostitution in Guatemala

- Prostitution in Haiti

- Prostitution in Honduras

- Prostitution in Jamaica

- Prostitution in Mexico

- Prostitution in Nicaragua

- Prostitution in Panama

- Prostitution in Trinidad and Tobago

- Prostitution in Nevada

South America

- Prostitution in Argentina

- Prostitution in Bolivia

- Prostitution in Brazil

- Prostitution in Chile

- Prostitution in Colombia

- Prostitution in Ecuador

- Prostitution in Guyana

- Prostitution in Paraguay

- Prostitution in Peru

- Prostitution in Suriname

- Prostitution in Uruguay

- Prostitution in Venezuela

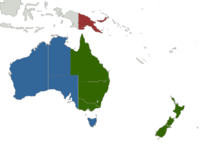

Oceania

Country details

Australia

In Australia, prostitution laws vary from State to State (see Prostitution in Australia). Most have decriminalised prostitution in varying ways. Regulation (sometimes known as legalisation) permits prostitution in certain forms, usually through zoning (confinement to certain areas) or licensing (licensing a limited number of prostitutes to work in certain areas of a city).

Kathleen Maltzhan reported for The Brisbane Institute in 2004[9] that in Victoria, women trafficked from overseas have been located in a number of legal brothels:

Legalisation legitimises prostitution. Despite the fact that most efforts to regulate prostitution come from a desire to limit the industry and protect women within it, the fact is that sex industry entrepreneurs always have more power than the women in it. They put huge resources into lobbying for recognition of the industry. Over time, what begins as a way to address sex industry criminality and violence becomes the means to portray prostitution as a legitimate industry which should not be criticised. Some elements in the sex industry will always ensure all men's demands are met. Trafficking is one way of doing this.We cannot return to the bad old days of criminalisation but we have to move beyond criminal control. An important principle in any discussion about prostitution is that the industry must be as safe and lucrative as possible for the women in it. If they want to leave they must have clear, accessible pathways out.

Canada

Current laws on prostitution in Canada, introduced in 2014, make it illegal to purchase sexual services but legal to sell them. This law was in response to a court decision made on December 20, 2013 by the Supreme Court of Canada which struck down all three previous prostitution laws as overbroad or grossly disproportionate to their intention. The court delayed the enforcement of its decision for one year to give the government a chance to write new laws.[10][11]

Although Canada is a federation, the criminal law applies throughout the country, the laws are the same all over Canada. The government included prostitution in the mandate of the Committee on Sexual Offences Against Children and Youth (the Badgley Committee), and the Special Committee on Prostitution and Pornography (the Fraser Committee) which helped to promote a significant body of research which has confirmed that approximately 70% of adult males and females working the street began their involvement in prostitution prior to their eighteenth birthday. This finding has spawned a lengthy debate about the causes and consequences of youth involvement in prostitution. The debate about causes of female youth prostitution centres around the role of sexual abuse and other familial factors that may contribute to a girl running away from or being thrown out of the home.

While the trend in other western countries has been to move away from criminal sanctions for prostitution, Canada has done the reverse, legislating a tougher anti-communication law (s.213) in 1986. More recently, various government committees and task forces have called for even tougher laws as well as more vigorous enforcement of the current legislation. In 1990, the Standing Committee on Justice recommended yet more strengthening of the laws including fingerprinting and photographing prostitutes and the removal of drivers licenses for those charged with communication for the purpose of prostitution.

China

As of February 2014, sex work is an administrative offence in China, and both workers and clients can be sentenced to 15 days’ detention and be given a fine of up to 5,000 yuan (US$825). The government's official view is that prostitution is an "ugly social phenomenon" and it is therefore illegal to solicit, sell and purchase sex in China.[12][13]

On the weekend of February 8 and 9, 2014, a Chinese national television network worked in tandem with Chinese police to conduct raids in the prefecture-level city of Dongguan. A news broadcast by the China Central Television (CCTV) network on February 8 was followed by the mobilisation of more than 6,000 policemen who then raided around 2,000 entertainment venues. On February 10, a three-month operation to eradicate the sex industry in the province of Guangdong was announced, along with the closure of 12 entertainment venues and the commencement of an investigation of 67 people.[12][13]

Public commentary in the wake of the operation was divided, with celebrity writer and television personality Sima Nan stating that legalization of sex work in China would not prevent the abuse of sex workers: "Indian society has legalised prostitution, but its situation in terms of rape crimes is the world’s most severe.” Wu Jiaxiang was one of several prominent intellectuals expressing concerns over the police's actions and raised the issue of legalization: “I have long advocated the legalisation of the sex trade, now is the time." Nicholas Bequelin, a Hong Kong-based researcher with Human Rights Watch who labelled the television coverage as "callous" stated: “It’s a much more wide-spaced debate about the sex trade than we have seen in the past. For the first time, there is a debate that includes the possibility of legalising sex work.”[12][13]

The general public's comments were also highlighted in the Chinese media and Wang Yongzhi, an IT worker from Beijing, commented: "There's no way to eradicate it. Legalization must take place under some narrowly-defined circumstances."[12][13] On social media, many viewers criticised the CCTV network, as they believed the broadcaster had exploited fellow ordinary Chinese citizens—a member of the Sina Weibo microblog platform wrote: “CCTV is heartless, but there’s love in this world."[14] The public response was explained by professor of sociology at Renmin University Zhou Xiaozheng in the following manner:

There are two sides of this anger: One is that, over the last 35 years of opening up, people have come to realize you sell your brains or you sell your body. Either way, it’s honest work. Like athletes, these women are selling their youth. … Attitudes on this issue are changing. Second, there’s a feeling that CCTV could pay attention to many other stories, like corrupt officials. ... Why is CCTV trying to take out vulnerable prostitutes who are just working?[14]

India

In India, prostitution (the exchange of sexual services for money) is legal,[15] but a number of related activities, including soliciting in a public place, keeping a brothel, pimping and pandering, are outlawed.[16]

Rajeshwari (1999) asserts that realistic accounts of prostitution in research contextualize it in the broad frame of the Indian socio-economic structure, adverting to the rural poverty and bonded labor, the gross exploitation of tribal, lower-caste and refugee women, urban red-light areas, disease, policy brutality and corruption, and the increasingly controversial issue of prostitutes' children. The country is a significant source, transit point, and destination for trafficked women.[17] According to UNICEF, India contained half of the one million children worldwide who enter the sex trade each year. Many indigenous tribal women were forced into sexual exploitation. In recent years, prostitutes began to demand legal rights, licenses, and reemployment training, especially in Mumbai, New Delhi, and Calcutta. In 2002, the Government signed the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Convention on Prevention and Combating Trafficking in Women and Children for Prostitution. The country is a significant source, transit point, and destination for many thousands of trafficked women. There was a growing pattern of trafficking in child prostitutes from Nepal and from Bangladesh (6,000 to 10,000 annually from each). Girls as young as seven years of age were trafficked from economically depressed neighborhoods in Nepal, Bangladesh, and rural areas to the major prostitution centers of Mumbai, Calcutta, and New Delhi. NGOs estimate that there were approximately 100,000 to 200,000 women and girls working in brothels in Mumbai and 40,000 to 100,000 in Calcutta.[18]

The traditional argument supporting prostitution as a phenomenon invokes male sexual need as a "natural" phenomenon that requires fulfillment outside of monogamous marriage – and the prostitute as servicing this need. Its theoretical defense is given in what is termed the "contractarian" argument, according to which the need for sexual gratification is a need similar to the need for food and fresh air (and hence gratification should be as readily available) and, further, that under conditions of "sound" prostitution, sexual services may be freely sold in the market place (Ericsson: 1980). Feminists reject the notion that the powerful male impulse must be satisfied immediately by a co-operative class of women, set aside for the purpose. This is seen as an adrocentric view of sexuality and as reinforcing the psychology of obtaining sexual satisfaction, by rape if necessary. In legal terms, the Indian Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act of 1956 criminalized the volitional act of "a female offering her body for promiscuous sexual intercourse for hire whether in money or in kind". But, under the revised 1986 Act, "prostitution" means "the sexual exploitation or abuse of persons for commercial purpose, and the expression 'prostitute' shall be constructed accordingly" – so there is not only no criminality if there is "offering by way of free contract", there is not even prostitution. More problematic is the status of the transgender people who eke out a living by begging, dancing or prostitution. Until 2014, Indian law recognized only two biological sexes. The PUCL (K) Report (2003), highlights, "The dominant discourse on human rights in India has yet to come to terms with [...] transgender communities. At stake is the human right to be different, the right to recognition of different pathways of sexuality, a right to immunity from the oppressive and repressive labeling of despised sexuality. Such a human right does not exist in India."

Philippines

Prostitution in the Philippines is illegal. It is a serious crime with penalties ranging up to life imprisonment for those involved in trafficking. It is covered by the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act.[19] Prostitution is sometimes illegally available through brothels (also known as casa), bars, karaoke bars (also known as KTVs), massage parlors, street walkers and escort services.

Scotland

The issue of prostitution law re-emerged in early 2014 following the motion of the Edinburgh City Council to delicence the local government area's saunas and massage parlours. Previously, sex work premises have been granted Public Entertainment Licences and, until 2001, the Scottish capital city also recognised tolerance zones for street-based sex work. Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) Jean Urquhart has put forward a motion to the Scottish Parliament in which she implores the Council to reconsider the delicencing process and represents the perspectives of sex worker organisations that continue to seek full decriminalisation—decriminalisation is supported by the World Health Organisation (WHO), Amnesty International and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).[20]

SCOT-PEP, a registered charity dedicated to the promotion of sex workers’ rights, in its official statement on the proposal from the Edinburgh City Council states:

Violence against sex workers increases when our workplaces are criminalised ... The further criminalisation of sex workers, those associated with sex workers, and our workplaces, has been shown again and again to endanger those working, whether they are there through choice, circumstance, or coercion. Sex workers need health services and a justice system that prioritises our safety - which has to include our safety if we continue working, as well as if we choose to 'exit'. The removal of the sauna licenses puts sex workers at risk.[21]

Spain

As of March 2014, the sex work industry is unregulated but not illegal; however, clients and sex workers—both street-based—have received fines in Barcelona, and the same is planned for the city of Madrid. The Spanish government's most recent data is from a 2007 parliamentary report that estimated the existence of around 400,000 sex workers in Spain who are part of an industry with an annual revenue of €50 million. Following an economic crisis in the country, increased numbers of women entered the industry and an independent sex worker organisation, Asociación de Profesionales del Sexo, composed of eight sex workers, conducted a four-hour introductory course for prospective sex workers in February 2014. A female psychologist who assisted with the delivery of the course explained to the media: "The only thing that this course is doing is empowering women who are already interested in working in the sector."[22]

Sweden, Norway and Iceland

In Sweden, Norway and Iceland it is illegal to pay for sex but not to offer sexual services, i.e., it is the client who commits a crime, but not the prostitute. In 1999, Sweden became the first country in the world to adopt this approach. All other prostitution-related activities (such as brothel-keeping and living off the earnings of prostitution) continue to be banned (see Prostitution in Sweden). The approach is referred to as the Swedish model, and is also sometimes referred as the Nordic model.[23] It is based on the premise that prostitution is a form of violence against women, and has three main components:[24]

- Though prostitution continues to be illegal, the buyer of sex is the offender and not the seller of sex (the prostitute, who is regarded as the victim). (Ekberg 2004:1191). Also, proponents of the law view trafficking of women and children for prostitution as being driven by the demand for prostitution domestically.[24] (Ekberg 2004:1200)

- It recognizes that women require another secure source of income in order to leave prostitution and that many women are forced by poverty to enter prostitution. It also recognizes that women require specialized exit services in order to build a life outside of prostitution. Therefore, the Swedish state continues to offer strong welfare provisions in general and specialized services to women exiting prostitution in particular.[24] (Ekberg 2004:1192)

- It recognizes public education as key to changing male attitudes related to prostitution. While legal measures can provide a deterrent and an important statement of society's goals, society as a whole must refuse to tolerate the purchase of sex before social norms will fully change.[24] (Ekberg 2004:1202)

Norway[25] and Iceland[26] adopted the Swedish model in 2009. However, the effectiveness of the Swedish model in reducing prostitution has been questioned by many, including the Western Australian Attorney General.[27] In 2010 the Swedish government admitted in its Country Progress Report to the UN General Assembly Special Session on AIDS that it could not estimate the number of people involved in prostitution since it is largely hidden, but that street prostitution was assumed to be only a fraction of total prostitution, most of which takes place indoors.[28]

A milder form of the policy is in effect in Finland, where buying of sexual services from prostitutes becomes illegal if it is linked to human trafficking, and is punishable by fines or up to 6 months jail.[29][30]

United States

- California

As of February 2014, sex work is illegal in the state of California and in the city of San Francisco, a First Offender Prostitution Program (FOPP)—also known as "john school"—has been established as a court diversion program for apprehended clients of the sex industry. The SAGE Project, one of the founders of the initiative, defines the FOPP as a "demand reduction strategy" and explains the program's philosophy in the following manner:

FOPP was founded on the theory that if male consumers had a better understanding of the risks and impact of their behavior when soliciting prostitution, they would cease to do so ... Understanding that everyone has different motivations, triggers and fears that inspire them to act, FOPP utilizes a variety of perspectives so that consumers are exposed to a range of experts who engage with the issue from different angles. This approach, the founders believed, would deliver a holistic understanding of the commercial sex industry that would empower sustained behavior change for a diverse set of individuals ... The FOPP model educates consumers on the harmful effects their actions have on themselves, those engaged in the sex industry, and their community.[31]

A chapter of the Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP)—a national advocacy group and decriminalization effort founded by and for sex workers in 2003—exists in the Bay Area of San Francisco and its members meet on a monthly basis. The chapter represents the sex-positive and activist ethos that underpins the local sex-workers' movement that also included the East Bay's Lusty Lady cooperative that, while it was open, remained the only business of its kind globally to be fully unionized and worker-owned. San Francisco is where the American sex-workers' rights movement was founded and decriminalization measures in Berkeley and San Francisco were garnering support as early as 2004.[32]

In November 2012, the Californian government passed Proposition 35 through ballot initiative, meaning that anyone who is a registered sex offender—including sex workers and those whose actions were not Internet-based—to turn over a list of all their Internet identifiers and service providers to law enforcement. The law expands the definition of trafficking to anyone who benefits financially from prostitution, regardless of intent, and sex workers have not only opposed the further criminalization of their work, but also the portrayal of all sex workers as victims that the law perpetuates.[32] The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Northern California (ACLU-NC) and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) filed a federal class-action lawsuit to block implementation of unconstitutional provisions of Proposition 35 in mid-2013 and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco heard oral arguments on September 10, 2013.[33][34] As of February 12, 2014, further information on the outcome of this lawsuit are yet to be published.

A media article published on February 8, 2014, provided details of a police sting operation in the Sonoma County area of California and the police officers involved experienced difficulties with the very high number of respondents to the false advertisement that they published on the Internet. After several hours, 10 men were arrested, followed by the arrest of former prosecutor and judicial candidate John LemMon—the authorities involved stated that the market is overwhelming. At the same time, the county District Attorney's Office is establishing a version of the FOPP for Sonoma County and the program will be active in mid-2014.[35]

On February 11, 2014, sex worker activists protested a San Francisco anti-trafficking panel discussion held by the San Francisco Collaborative Against Human Trafficking, as they believe that it will further criminalize adults in the sex industry. Maxine Doogan, an organizer with the Erotic Service Providers Union, stated: "Their goal is to disappear the whole sex industry by criminalizing the people that participate in it. Targeting our customers is a flawed approach." Doogan also included in a press release announcing the protest that the term "john" as a descriptor for sex work clients is demeaning and dehumanizes customers.[36]

References

- ↑ "Sex Workers, Prostitution, HIV and AIDS".

- ↑ Increasing prostitution driven by poverty in drought-stricken – Welthungerhilfe. Welthungerhilfe.de. Retrieved on 2012-01-11.

- ↑ Sex Workers, Prostitution and AIDS. Avert.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-11.

- ↑ 2008 Human Rights Report: Thailand. State.gov (2009-02-25). Retrieved on 2012-01-11.

- ↑ Hongo, Jun. "Law bends over backward to allow 'fuzoku'". japantimes.co.jp. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ Deena Guzder "UNICEF: Protecting Children from Commercial Sexual Exploitation". Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. August 20, 2009

- ↑ Policing and Crime Act 2009. Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved on 2012-01-11.

- ↑ Policing and Crime | UK | Anti-trafficking | Exploitation | Sex Industry | The Naked Anthropologist. Nodo50.org (2010-04-06). Retrieved on 2012-01-11.

- ↑ Kathleen Maltzhan (2004). "Combating trafficking in women: where to now?". Archived from the original on 30 June 2004. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ "Supreme Court strikes down Canada's prostitution laws". CBC News. 20 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Supreme Court of Canada (20 December 2013). "CITATION: Canada (Attorney General) v. Bedford, 2013 SCC 72". DocumentCloud. The Knight Foundation. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Patrick Boehler (11 February 2014). "Dongguan sex worker reports stoke debate about legalising prostitution". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Louise Watt (11 February 2014). "Reaction to prostitution crackdown in China's 'sex capital' suggests views may be shifting". Brandon Sun. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- 1 2 Julie Makinen (10 February 2014). "China TV expose on sex workers sparks angry backlash". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ "Prostitution: should the laws be changed?". BBC News. 3 August 2001.

- ↑ "2008 Human Rights Reports:India". State.gov. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "2008 Human Rights Reports: India. ''US Department of State'' June 21, 2010". State.gov. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "The staggering incoherence of India's prostitution laws. ''Vancouver Sun'' June 21, 2010". Rohan.sdsu.edu. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ Philippine Laws, Statutes And Codes - Chan Robles Virtual Law Library

- ↑ "Jean urges decriminalisation for sex workers’ safety". Jean Urquhart MSP Independent MSP for the Highlands and Islands region. Jean Urquhart. 11 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ↑ "SCOT-PEP STATEMENT on Edinburgh City Council's decision to withdraw sauna licensing". SCOT-PEP. SCOT-PEP. February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ↑ Ashifa Kassam (3 March 2014). "Spanish 'prostitution for beginners' workshop angers prominent feminists". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ↑ Raymond, Janice, Trafficking, Prostitution, and the Sex Industry: The Nordic Legal Model July 2010

- 1 2 3 4 Ekberg, Gunilla, "The Swedish Law That Prohibits the Purchase of Sexual Services: Best Practices for Prevention of Prostitution and Trafficking in Human Beings" in "Violence Against Women" Vol 10(10) 2004.

- ↑ "New Norway law bans buying of sex". BBC News. 31 December 2008. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ Fréttir / A new law makes purchase of sex illegal in Iceland 21 April 2009 Jafnréttisstofa

- ↑ "Attorney General challenges anti-prostitution lobby. The Record, 17 June 2010". Therecord.com.au. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2015-09-14. Sweden – 2010 Country Progress Report, UNGASS

- ↑ "Uutiset - FINLEX ®". Finlex.fi. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ↑ "Laki rikoslain 1 ja 20 luvun muuttamisesta 743/2006 - Säädökset alkuperäisinä - FINLEX ®". Finlex.fi. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ↑ "First Offender Prostitution Program (FOPP)". The SAGE Project. The SAGE Project. 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- 1 2 Ellen Cushing (17 October 2012). "Redefining Sex Work". East Bay Express. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ Hanni Fakhoury (9 September 2013). "Court to Hear Arguments on Right to Anonymous Speech in Prop. 35 Case". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ "Doe v. Harris". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Electronic Frontier Foundation. 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ Mary Callahan (8 February 2014). "Sonoma County sting shows a changing approach to prostitution". The Press Democrat. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ↑ Sam Levin (10 February 2014). "Sex Workers to Protest Anti-Trafficking Panel, Say 'John' Label Is Offensive". East Bay Express. Retrieved 11 February 2014.