Propylaea

.jpg)

A propylaea, propylea or propylaia (/ˌprɒpɪˈliːə/; Greek: Προπύλαια) is any monumental gateway in Greek architecture. Much the best known Greek example is the propylaea that serves as the entrance to the Acropolis in Athens. The Greek Revival Brandenburg Gate of Berlin and the Propylaea in Munich both evoke the central portion of the Athens propylaea.

The Greek word προπύλαιον propylaeon (propylaeum is the Latin version) is the union of the prefix προ- pro-, "before, in front of" plus the plural of πύλη pyle "gate," meaning literally "that which is before the gates," but the word has come to mean simply "gate building."

Propylaea of the Athenian Acropolis

The monumental gateway to the Acropolis, the Propylaea was built under the general direction of the Athenian leader Pericles, but Phidias was given the responsibility for planning the rebuilding of the Acropolis as a whole at the conclusion of the Persian Wars. According to Plutarch, the Propylaea was designed by the architect Mnesicles, but we know nothing more about him.[1] Construction began in 437 BC and was terminated in 432, when the building was still unfinished.

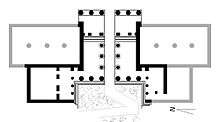

The Propylaea was constructed of white Pentelic marble and gray Eleusinian marble or limestone, which was used only for accents. Structural iron was also used, though William Bell Dinsmoor[2] analyzed the structure and concluded that the iron weakened the building. The structure consists of a central building with two adjoining wings on the west (outer) side, one to the north and one to the south.

The core is the central building, which presents a standard six-columned Doric façade both on the West to those entering the Acropolis and on the east to those departing. The columns echo the proportions (not the size) of the columns of the Parthenon. There is no surviving evidence for sculpture in the pediments.

The central building contains the gate wall, about two-thirds of the way through it. There are five gates in the wall, one for the central passageway, which was not paved and lay along the natural level of the ground, and two on either side at the level of the building's eastern porch, five steps up from the level of the western porch. The central passageway was the culmination of the Sacred Way, which led to the Acropolis from Eleusis.

Entrance into the Acropolis was controlled by the Propylaea. Though it was not built as a fortified structure, it was important that people not ritually clean be denied access to the sanctuary. In addition, runaway slaves and other miscreants could not be permitted into the sanctuary where they could claim the protection of the gods. The state treasury was also kept on the Acropolis, making its security important.

The gate wall and the eastern (inner) portion of the building sit at a level five steps above the western portion, and the roof of the central building rose on the same line. The ceiling in the eastern part of the central building was famous in antiquity, having been called by Pausanias (about 600 years after the building was finished) "...down to the present day unrivaled." It consisted of marble blocks carved in the shape of ceiling coffers and painted blue with gold stars.

The Colonnades

The outer (western) wings to the right and left of the central building stood on the same platform as the western portion of the central building but were much smaller, not only in plan but in scale. Like the central building, the wings use Doric colonnades and Doric entablatures. The central building also has an Ionic colonnade on either side of the central passageway between the western (outer) Doric colonnade and the gate wall. This is therefore the first building known to us with Doric and Ionic colonnades visible at the same time. It is also the first monumental building in the classical period to be more complex than a simple rectangle or cylinder.

The western wing on the north (to the left as one enters the Acropolis) was famous in antiquity as the location of paintings of important Greek battles. Pausanias reports their presence, but few scholars believe the room was planned to hold them. Recent scholarship, following the lead of John Travlos (Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens, New York, 1971), has taken the northern wing to have been a room for ritual dining. The evidence for that is the off-center doorway and the position near the entrance to the Acropolis.

The wing on the south, though much smaller, was clearly designed to make the whole structure appear to be symmetrical. It seems only to have functioned as an access route to the Temple of Athena Nike, which stood to the south and further west, on a raised bastion.

Plans for eastern and western side of Propylaea

There were two wings planned for the east side of the Propylaea, facing in toward the Acropolis. Preparations for both wings are apparent at the eastern end of the central building and along the side walls, but it seems that the plan for a southern wing was abandoned early in the construction process since the old fortification wall was not demolished, as required for that wing.

The north wing was not built either. Had it been constructed, it seems that the level of the floor would have been problematic. To the extent that preparations had been made, they were for a floor at the level of the western portion of the building, considerably below the level required on the East.

As a result of the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta in 431 BC, the Propylaea was never completed. Not only are the eastern wings missing, the wall surfaces were not trimmed to their finished shapes, and so-called lifting bosses remain on many blocks. (Lifting bosses have long been called such but are now recognized to have been for another purpose, though that other purpose is not agreed. See A. Trevor Hodge, "Bosses Reappraised," Omni Pede Stare: Saggi Architettonici e circumvesuviani in memoriuam Jos de Waele, Mols & Moormann, eds.)

Later history

The Propylaea survived intact through the Greek, Roman and Byzantine periods. During the period of the Duchy of Athens, it served as the palace of the Acciaioli family, who ruled the duchy from 1388 to 1458. It was severely damaged by an explosion of a powder magazine in 1656, foreshadowing the even more grievous damage to the Parthenon from a similar cause in 1687. A Frankish tower, erected on the south wing, was pulled down in 1874.

Restoration

Today the Propylaea has been partly restored, since 1984 under the direction of Tasos Tanoulas, and serves as the main entrance to the Acropolis for the many thousands of tourists who visit the area every year. In the period before the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, the Propylaea was shrouded in scaffolding as restoration work was undertaken. At the end of 2009 all scaffolding was removed, and the building is now open fully to view again. The famous ceilings have even been partly restored.

The restoration of the Central Building of the Propylaea was awarded a European Union Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Award in 2013.[3][4]

Other propylaea

Propylaea outside the Greco-Roman world

The oldest known freestanding propylaeum is the one located at the palace area in Pasargadae, an Achaemenid capital.[5]

A covered passage, called "the Propylaeum", faces the Palace of Darius at Susa.[6]

Notes

- ↑ , Plutarch: Pericles 13.7.

- ↑ Dinsmoor, William Bell (1922), "Structural Iron in Greek Architecture," American Journal of Archaeology, XXVI

- ↑ http://www.europanostra.org/awards/98/

- ↑ http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-13-279_en.htm

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/pasargadae

- ↑ "SUSA iii. THE ACHAEMENID PERIOD – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

References

- Berve, H.; Gruben, G.; and Hirmer, M. Greek Temples, Theaters, and Shrines (New York, 1963). A general look at selected Greek structures.

- Bohn, R., Die Propyläen der Akropolis zu Athen (Berlin & Stuttgart, 1882). The first thorough study of the Propylaea.

- Bundgaard, J. A., Mnesicles, A Greek Architect at Work (Copenhagen, 1957). A careful look at both the building and the implications for architectural planning. Idiosyncratic.

- Darling, Janina K.; Architecture of Greece, 2004, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0313321523, 9780313321528, google books - good account of the Athens Propylaea on pp. 142–145, available online

- Dinsmoor, William Bell (1922), "Structural Iron in Greek Architecture," American Journal of Archaeology, XXVI

- Dinsmoor, W. B., The Architecture of Ancient Greece (New York, 1975 - but actually a reprint of the 1950 publication). A general book on Greek architecture; dated in many areas but valuable for the Propylaea.

- Dinsmoor, W. B., Jr., The Propylaia I: The Predecessors (Princeton, 1980). A careful study of the predecessors of the Propylaea.

- Eiteljorg, Harrison, II, The Entrance to the Acropolis Before Mnesicles (Dubuque, 1993). A careful study of the predecessors of the Propylaea, with very different conclusions from those of Dinsmoor above.

- Lawrence, A. W., Greek Architecture (Baltimore, 1973). A general book on Greek architecture.

- Robertson, D.S. Greek and Roman Architecture' (Cambridge, 1969). A general book on Greek and Roman architecture. Available in paper, this may be the best place to begin for those with no knowledge of ancient architecture.

- Rhodes, R. F., Architecture and Meaning on the Athenian Acropolis (Cambridge, 1995). A modern view of the Acropolis and its monuments.

- Tanoulas, T.; Ioannidou, M.; and Moraitou, A., Study for the Restoration of the Propylaea, Volume I (Athens, 1994) Superb drawings and many careful observations from those responsible for modern work on the Propylaea.

- Tanoulas, T., The Propylaea of the Athenian Acropolis during the Middle Ages, (Athens, 1997) Two volumes. In modern Greek, but includes a lengthy English summary and many drawings and photographs.

- Travlos, J., Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens (London, 1971). An encyclopedic approach to the monuments of Athens.

- Waele, J. A. K. E. de, The Propylaia of the Akropolis in Athens: The Project of Mnesicles (Amsterdam, 1990). More of a study of planning processes than of the building.

- The Perseus Project An electronic resource that provides quick information, but some of the information about the Propylaea was incorrect when the site was last checked. Several good photographs of the Propylaea are available through the Perseus project.

- William B. Dinsmoor, William B. Dinsmoor, Jr., The Propylaia to the Athenian Akropolis II: The Classical Building Edited by Anastasia Norre Dinsmoor. Princeton, NJ: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2004. This should be read with great care and in conjunction with the review, by T. Tanoulas, in the Bryn Mawr Classical Review at http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2008/2008-04-17.html.. :)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Propylaea. |

- Photo album

- Propylaea.org – leads to a variety of material, some scholarly, but many photographs as well

- The Propylaia of the Athenian Acropolis - Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism

- Propylaea Central Building, Acropolis, Athens, GREECE – Europa Nostra

Coordinates: 37°58′18.20″N 23°43′30.50″E / 37.9717222°N 23.7251389°E