Lockheed A-12

| A-12 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A-12 aircraft, serial number 06932 | |

| Role | High-altitude reconnaissance aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Corporation |

| First flight | 26 April 1962 |

| Introduction | 1967 |

| Retired | 1968 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary user | Central Intelligence Agency |

| Number built | A-12: 13; M-21: 2 |

| Variants | Lockheed YF-12 |

| Developed into | Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird |

The Lockheed A-12 was a reconnaissance aircraft built for the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) by Lockheed's Skunk Works, based on the designs of Clarence "Kelly" Johnson. The aircraft was designated A-12, the 12th in a series of internal design efforts for "Archangel", the aircraft's internal code name. It competed in the CIA's "Oxcart" program against the Convair Kingfish proposal in 1959, and won for a variety of reasons.

CIA's representatives initially favored Convair's design for its smaller radar cross-section, but the A-12's specifications were slightly better and its projected cost was much less. The companies' respective track records proved decisive. Convair's work on the B-58 had been plagued with delays and cost overruns, whereas Lockheed had produced the U-2 on time and under budget. In addition, it had experience running a “black” project.[1]

The A-12 was produced from 1962 to 1964, and operated from 1963 to 1968. It was the precursor to the twin-seat U.S. Air Force YF-12 prototype interceptor, M-21 drone launcher, and the SR-71 Blackbird, a slightly longer variation able to carry a heavier fuel and camera load. The A-12's final mission was flown in May 1968, and the program and aircraft retired in June. The program was officially revealed in the mid-1990s.[2]

A CIA officer later wrote, "OXCART was selected from a random list of codenames to designate this R&D and all later work on the A-12. The aircraft itself came to be called that as well."[3] The crews named the A-12 the Cygnus, suggested by pilot Jack Weeks to follow the Lockheed practice of naming aircraft after celestial bodies.[4]

Design and development

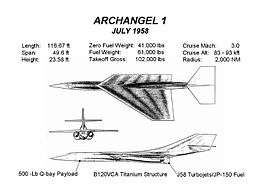

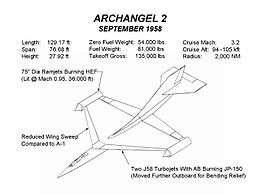

With the failure of the CIA's Project Rainbow to reduce the radar cross-section (RCS) of the U-2, preliminary work began inside Lockheed in late 1957 to develop a follow-on aircraft to overfly the Soviet Union. Under Project Gusto the designs were nicknamed "Archangel", after the U-2 program, which had been known as "Angel". As the aircraft designs evolved and configuration changes occurred, the internal Lockheed designation changed from Archangel-1 to Archangel-2, and so on. These names for the evolving designs soon simply became known as "A-1", "A-2", etc.[5] The CIA program to develop the follow-on aircraft to the U-2 was code-named Oxcart.[6]

These designs had reached the A-11 stage when the program was reviewed. The A-11 was competing against a Convair proposal called Kingfish, of roughly similar performance. However, the Kingfish included a number of features that greatly reduced its radar cross-section, which was seen as favorable to the board. Lockheed responded with a simple update of the A-11, adding twin canted fins instead of a single right-angle one, and adding a number of areas of non-metallic materials. This became the A-12 design. On 26 January 1960, the CIA ordered 12 A-12 aircraft.[7]

New materials and production techniques

Because the A-12 was way ahead of its time, many new technologies had to be invented specifically for the Oxcart project, some still in use today. One of the biggest problems that engineers faced at that time was working with titanium.[8]

In his book Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed, Ben Rich stated, "Our supplier, Titanium Metals Corporation, had only limited reserves of the precious alloy, so the CIA conducted a worldwide search and using third parties and dummy companies, managed to unobtrusively purchase the base metal from one of the world's leading exporters – the Soviet Union. The Russians never had an inkling of how they were actually contributing to the creation of the airplane being rushed into construction to spy on their homeland."[9]

Before the A-12, titanium was used only in high-temperature exhaust fairings and other small parts directly related to supporting, cooling, or shaping high-temperature areas on aircraft like those subject to the greatest kinetic heating from the airstream, such as wing leading edges. The A-12, however, was constructed mainly of titanium and some composite materials made from iron ferrite and silicon laminate, both combined with asbestos to absorb radar returns and make the aircraft more stealthy.[10][11][12]

Flight testing

After development and production at the Skunk Works, in Burbank, California, the first A-12 was transferred to Groom Lake test facility.[13] On 25 April 1962 it was taken on its first (unofficial and unannounced) flight with Lockheed test pilot Louis Schalk at the controls.[14] The first official flight later took place on 30 April and subsequent supersonic flight on 4 May 1962, reaching speeds of Mach 1.1 at 40,000 ft (12,000 m).[15]

The first five A-12s, in 1962, were initially flown with Pratt & Whitney J75 engines capable of 17,000 lbf (76 kN) thrust each, enabling the J75-equipped A-12s to obtain speeds of approximately Mach 2.0. On 5 October 1962, with the newly developed J58 engines, an A-12 flew with one J75 engine, and one J58 engine. By early 1963, the A-12 was flying with J58 engines, and during 1963 these J58-equipped A-12s obtained speeds of Mach 3.2.[16] Also, in 1963, the program experienced its first loss when, on 24 May, "Article 123"[17] piloted by Kenneth S. Collins crashed near Wendover, Utah.[18]

The reaction to the crash illustrated the secrecy and importance of the project. The CIA called the aircraft a Republic F-105 Thunderchief as a cover story;[19] local law enforcement and a passing family were warned with "dire consequences" to keep quiet about the crash. Each was also paid $25,000 in cash to do so; the project often used such cash payments to avoid outside inquiries into its operations. The project received ample funding; contracted security guards were paid $1,000 monthly with free housing on base, and chefs from Las Vegas were available 24 hours a day for steak, Maine lobster, or other requests.[17]

In June 1964, the last A-12 was delivered to Groom Lake,[20] from where the fleet made a total of 2,850 test flights.[19] A total of 18 aircraft were built through the program's production run. Of these, 13 were A-12s, three were prototype YF-12A interceptors for the U.S. Air Force (not funded under the OXCART program), and two were M-21 reconnaissance drone carriers. One of the 13 A-12s was a dedicated trainer aircraft with a second seat, located behind the pilot and raised to permit the Instructor Pilot to see forward. The A-12 trainer, known as "Titanium Goose", retained the J75 power plants for its entire service life.[21]

Three more A-12s were lost in later testing. On 9 July 1964, "Article 133" crashed while making its final approach to the runway when a pitch-control servo device froze at an altitude of 500 feet (150 metres) and airspeed of 200 knots (370 kilometres per hour) causing it to begin a smooth steady roll to the left. Lockheed test pilot Bill Parks could not overcome the roll. At about a 45 degree bank angle and 200 feet (61 metres) altitude he ejected and was blown sideways out of the aircraft. Although he was not very high off the ground, his parachute did open and he landed safely.[22][23]

On the 28 December 1965, the third A-12 was lost when "Article 126" crashed 30 seconds after takeoff when a series of violent yawing and pitching actions was followed very rapidly with the aircraft becoming uncontrollable. Mele Vojvodich was scheduled to take aircraft number 126 on a performance check flight which included a rendezvous beacon test with a KC-135 tanker and managed to eject safely 150 feet (46 metres) to 200 feet (61 metres) above the ground. A post-crash investigation revealed that the primary cause of the accident was a maintenance error in that the flight line technician was negligent in performing his duty when he connected the wiring harnesses for the yaw and pitch rate gyroscopes of the stability augmentation system in reverse. It was also found that a contributing cause was a design deficiency which made it possible to physically connect the wiring harnesses in reverse.[24]

The first fatality of the Oxcart program occurred on 5 January 1967, when "Article 125" crashed, killing CIA pilot Walter Ray when the aircraft ran out of fuel while on its descent to the test site. No precise cause could be established for the loss and it was considered most probable that a fuel gauging error led to fuel starvation and engine flameout 67 miles (108 kilometres) from the base. Ray ejected successfully but was unable to separate from the seat and was killed on impact.[25][26]

Operational history

Although originally designed to succeed the U-2 in overflights over the Soviet Union and Cuba, the A-12 was never used for either role. After a U-2 was shot down in May 1960, the Soviet Union was considered too dangerous to overfly except in an emergency (and overflights were no longer necessary,[27] thanks to reconnaissance satellites) and, although crews trained for flights over Cuba, U-2s continued to be adequate there.[28]

The Director of the CIA decided to deploy some A-12s to Asia. The first A-12 arrived at Kadena Air Base on Okinawa on 22 May 1967. With the arrival of two more aircraft on 24 May, and 27 May this unit was declared to be operational on 30 May, and it began Operation Black Shield on 31 May.[29] Mel Vojvodich flew the first Black Shield operation, over North Vietnam, photographing surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites, flying at 80,000 ft (24,000 m), and at about Mach 3.1. During 1967 from the Kadena Air Base, the A-12s carried out 22 sorties in support of the War in Vietnam. Then in 1968, Black Shield conducted operations in Vietnam and it also carried out sorties during the Pueblo Crisis with North Korea.[6]

Mission profile

Operations and maintenance at Kadena began with the receipt of alert notification. Both a primary aircraft and pilot and a back-up aircraft and pilot were selected. The aircraft were given thorough inspection and servicing, all systems were checked, and the cameras equipped. Pilots received a detailed route briefing in the early evening prior to the day of flight. On the morning of the flight a final briefing occurred, at which time the condition of the aircraft and its systems was reported, last-minute weather forecasts reviewed, and other relevant intelligence communicated, together with any amendments or changes in the flight plan. Two hours prior to take-off the primary pilot had a medical examination, got into his suit, and was taken to the aircraft. If any malfunctions developed on the primary aircraft, the back-up could execute the mission one hour later.

A typical route profile for a mission over North Vietnam included a refueling shortly after take-off, south of Okinawa, the planned photographic pass or passes, withdrawal to a second aerial refueling in the Thailand area, and return to Kadena. Its turning radius of 86 miles (138 kilometres) was such, however, that on some mission profiles it might be forced during its turn to intrude into Chinese airspace.

Once landed, the camera film was removed from the aircraft, boxed, and sent by special plane to the processing facilities. Film from earlier missions was developed at the Eastman Kodak plant in Rochester, New York. Later an Air Force Center in Japan carried out the processing in order to place the photointelligence in the hands of American commanders in Vietnam within 24 hours of completion of a mission.[6]

SAM evasion over North Vietnam

There were a number of reasons leading to the retirement of the A-12, but one major concern was the growing sophistication of Soviet-supplied SAM sites that it had to contend with over mission routes. In 1967, the vehicle was tracked with acquisition radar over North Vietnam, but the SAM site was unsuccessful with the Fan Song guidance radar used to home the missile to the target.[30] On 28 October a North Vietnamese SAM site launched a single, albeit unsuccessful, missile. Photography from this mission documented the event with photographs of missile smoke above the SAM firing site, and with pictures of the missile and of its contrail. Electronic countermeasures equipment appeared to perform well against the missile firing.

During a flight on 30 October 1967, pilot Dennis Sullivan detected radar tracking on his first pass over North Vietnam. Two sites prepared to launch missiles but neither did. During the second pass, at least six missiles were fired, each confirmed by missile vapor trails on mission photography. Looking through his rear-view periscope, Sullivan saw six missile vapor trails climb to about 90,000 ft (27,000 m) before converging on his aircraft. He noted the approach of four missiles, and although they all detonated behind him, one came within 100 yards (91 metres) to 200 yards (180 metres) of his aircraft.[31] Post-flight inspection revealed that a piece of metal had penetrated the lower right wing fillet area and lodged against the support structure of the wing tank. The fragment was not a warhead pellet but may have been a part of the debris from one of the missile detonations observed by the pilot.[6]

The SA-2 'Guideline' was an early missile design intended to counter lower and slower aircraft like the B-52 and B-58. In response to faster, higher-flying designs like the B-70, the Soviets had begun development of greatly improved missile systems, notably the SA-5 'Gammon'. The Soviet Air Defence Forces (Protivo-Vozdushnaya Oborona, PVO) cleared the SA-5 for service in 1967;[32] if deployed to Vietnam, it would have provided an additional risk to the A-12.

The final Black Shield mission over North Vietnam and the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) was flown on the 8 March 1968. Good quality photography was obtained of Khe Sanh and the Laos, Cambodia, and South Vietnamese border areas. No usable photography was obtained of North Vietnam due to adverse weather conditions. There was no indication of a hostile weapons reaction and no ECM systems were activated.[33]

Final missions over North Korea

In 1968 three missions were flown over North Korea. The first mission occurred during a very tense period following seizure of the Navy intelligence ship Pueblo on the 23rd of January. The aim was to discover whether the North Koreans were preparing any large scale hostile move following this incident and to actually find where the Pueblo was hidden. The ship was found anchored in an inlet in Wonsan Bay attended by two North Korean patrol boats and guarded by three Komars.[34] Chinese tracking of the flight was apparent, but no missiles were fired at the Oxcart.[35]

The second mission on the 19 February 1968 was also the first two-pass mission over North Korea. The Oxcart vehicle photographed 84 primary targets plus 89 bonus targets. Scattered clouds covered 20 percent of the area, concealing the area in which the USS Pueblo was photographed on the previous mission. One new SA-2 site was identified near Wonsan.[36]

Retirement

Even before the A-12 became operational, its intended purpose — replacing the U-2 in overflights of the Soviet Union — had become less likely. Soviet air defenses had advanced to the point that even an aircraft flying faster than a rifle bullet at the edge of space could be tracked. Upgrades to Soviet radar systems increased their blip-to-scan ratios, rendering the A-12 vulnerable.[37] In any event, President Kennedy had stated publicly that the United States would not resume such missions. By 1965, moreover, the photoreconnaissance satellite programs had progressed to the point that manned flights over the Soviet Union were unnecessary to collect strategic intelligence.[25]

The A-12 program was ended on 28 December 1966[38] — even before Black Shield began in 1967 — due to budget concerns[39] and because of the SR-71, which began to arrive at Kadena in March 1968.[40] The twin-seat SR-71 was heavier and flew slightly lower and slower than the A-12.[41]

Ronald L. Layton flew the 29th and final A-12 mission on 8 May 1968, over North Korea.[42] On 4 June 1968, just 2½ weeks before the fleet's retirement, an A-12 from Kadena, piloted by Jack Weeks, was lost over the Pacific Ocean near the Philippines while conducting a functional check flight after the replacement of one of its engines.[39][43] Frank Murray made the final A-12 flight on 21 June 1968, to Palmdale, California, storage facility.[44]

On 26 June 1968, Vice Admiral Rufus L. Taylor, the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, presented the CIA Intelligence Star for valor to Weeks' widow and pilots Collins, Layton, Murray, Vojvodich, and Dennis B. Sullivan for participation in Black Shield.[39][45][46]

The deployed A-12s and the eight non-deployed aircraft were placed in storage at Palmdale. All surviving aircraft remained there for nearly 20 years before being sent to museums around the U.S. On 20 January 2007, despite protests by Minnesota's legislature and volunteers who had maintained it in display condition, the A-12 preserved in Minneapolis, Minnesota, was sent to CIA headquarters to be displayed there.[47]

Timeline

Major events in the development and operation of the A-12 and its successor, the SR-71, include:

- 16 August 1956: Following Soviet protest of U-2 overflights, Richard M. Bissell, Jr. conducts the first meeting on reducing the radar cross section of the U-2. This evolves into Project Rainbow, a bid to prolong the aircraft's operational life through a package of modifications. Called "Trapeze", these added wires and paints impregnated with tiny iron ferrite beads and ECM systems. The modified U-2s were called "Dirty Birds". Ultimately, the program failed to substantially reduce the U-2's RCS, leading to the decision to develop a new aircraft with stealth characteristics.[48]

- December 1957: Lockheed begins designing subsonic stealthy aircraft under what will become Project Gusto.

- 24 December 1957: First J-58 engine run.

- 21 April 1958: Kelly Johnson makes first notes on a Mach-3 aircraft, initially called the U-3, but eventually evolving into Archangel I. Kelly noted in his A-12 diary, "I drew up the first Archangel proposal for a Mach-3.0 cruise airplane having a 4,000-nm [4,606-mile;7412-km] range at 90,000 to 95,000 ft [27432 to 28956 m]".[49]

- November 1958: The Land panel provisionally selects Convair FISH (B-58-launched parasite) over Lockheed's A-3. The A-3 was an unstaged (non-parasite) aircraft that cruised at Mach 3.2 at 95,000 feet (29,000 metres). The Land Panel favored Convair's design, which had a smaller radar cross section than the A-3. On 22 December, Convair was instructed to continue FISH's development and to plan for production. While Convair struggled with aerodynamic issues, Lockheed pursued its own efforts on high-speed, high-altitude reconnaissance designs, evolving from A-4 through A-11. The first three configurations, A-4 through A-6, were smaller, self-launched aircraft with vertical surfaces hidden above the wing. The aircraft used a variety of propulsion schemes that included turbojets, ramjets, and rockets. None met the required mission radius of 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 kilometres), leading Lockheed to conclude that maximum performance and low radar cross section were mutually exclusive. The A-10 and A-11 configurations were larger aircraft that also focused on performance at the expense of radar cross section. Lockheed submitted the more refined A-11 at the next Land Panel review.[50]

- June 1959: The Land panel provisionally selects the A-11 over FISH, instructing both companies to re-design their aircraft. In July, the Land panel rejected both the Convair and Lockheed proposals. The Convair FISH used unproven ramjet engine technology and would be launched from a modified B-58B Hustler which was canceled in June. The susceptibility of the A-11 to radar detection was considered too great. On 20 August, both firms provided specifications for their revised proposals.[51]

- 14 September 1959: CIA awards antiradar study, aerodynamic structural tests, and engineering designs, selecting the A-12 over rival Convair's Kingfish. Project Oxcart established. The A-12 design, a combination of their A-7 and A-11 submissions, emphasized low radar cross section, extremely high altitude and high-speed performance. Earlier, on 3 September, Project GUSTO was concluded and Project OXCART, to build the A-12, was begun.[52]

- 26 January 1960: The CIA formally placed an order for 12 A-12 aircraft.

- 1 May 1960: Francis Gary Powers is shot down in a U-2 over the Soviet Union. He safely ejected and was turned over to Soviet authorities. A well-publicized trial followed and he was sentenced to 10 years "deprivation of liberty," serving three years in prison before being exchanged in 1962 for Soviet spy Rudolf Abel. Upon return he was debriefed extensively.[53]

- 26 April 1962: First flight of A-12 with Lockheed test pilot Louis Schalk at Groom Lake. The previous day, it had made an unofficial and unannounced flight, in keeping with Lockheed tradition. Schalk flew the plane less than 2 miles (3.2 kilometres), at an altitude of about 20 feet (6.1 metres), because of serious wobbling caused by improper hookup of some navigational controls. Instead of circling around and landing, Schalk landed in the lake bed beyond the end of the runway. The next day, the official flight took place with the landing gear down, just in case. The flight lasted about 40 minutes. The takeoff was perfect, but after the A-12 got to about 300 feet (91 metres) it started shedding all the "pie slice" fillets of titanium on the left side of the aircraft and one fillet on the right. (On later aircraft, those pieces were paired with triangular inserts made of radar-absorbing composite material.) Technicians spent four days finding and reattaching the pieces. Nonetheless, the flight pleased Johnson.[54][55]

- 13 June 1962: SR-71 mock-up reviewed by USAF.

- 30 July 1962: J58 engine completes pre-flight testing.

- October 1962: A-12s first flown with J58 engines

- 28 December 1962: Lockheed signs contract to build six SR-71 aircraft. Earlier in the month, on 17 December the 5th A-12 arrived at Groom Lake and the Air Force expressed an interest in obtaining reconnaissance versions of the Blackbird. Lockheed begins weapons systems development for the AF-12. Kelly Johnson obtained approval to design a Mach-3 Blackbird fighter/bomber.[56]

- January 1963: A-12 fleet operating with J58 engines

- 24 May 1963: Loss of first A-12 (#60–6926)

- 20 July 1963: First mach 3 flight

- 7 August 1963: First flight of the YF-12A with Lockheed test pilot James Eastham at Groom Lake.

- June 1964: Last production A-12 delivered to Groom Lake.

- 25 July 1964: President Johnson makes public announcement of SR-71.

- 29 October 1964: SR-71 prototype (#61-7950) delivered to Palmdale.

- 22 December 1964: First flight of the SR-71 with Lockheed test pilot Bob Gilliland at AF Plant #42. First mated flight of the MD-21 with Lockheed test pilot Bill Park at Groom Lake.

- 28 December 1966: Decision to terminate A-12 program by June 1968.

- 31 May 1967: A-12s conduct Black Shield operations out of Kadena

- 3 November 1967: A-12 and SR-71 conducted a reconnaissance fly-off, codenamed NICE GIRL. Between 20 October and 3 November 1967, A-12s and SR-71s flew three identical routes along the Mississippi River about one hour apart with their collection systems on. The results were inconclusive. The A-12's camera had a wider swath but the SR-71 collected types of intelligence the A-12 could not of a good quality; however, some sensors would typically be removed to make room for ECM gear.[57] There was little difference in range - the SR-71 carried more fuel - the A-12 had an altitude advantage of from 2,000 feet (610 metres) to 5,000 feet (1,500 metres) over the SR-71 at the same Mach number, being a lighter aircraft. The radar cross section of both aircraft in a clean configuration was relatively low; the SR-71 in a full sensor configuration was somewhat higher due to its larger size and was appreciably larger again with the side-looking radar antenna installed.[58] The A-12 was designed to optionally utilize one of three different types of high resolution cameras; the highest of which provided a 63 nautical miles (117 kilometres) wide continuous swath of 1 foot (0.30 metres) resolution. The SR-71 had the simultaneous capability for photography and ELINT. Its imagery was 1 foot (0.30 metres) resolution of two separate 5 miles (8.0 kilometres) swath wide strips positioned up to 19.6 miles (31.5 kilometres) apart on either side of the aircraft.[59]

- 26 January 1968: North Korea A-12 overflight by Jack Weeks photo-locates the captured USS Pueblo in Changjahwan Bay harbor.[60]

- 5 February 1968: Lockheed ordered to destroy A-12, YF-12 and SR-71 tooling.

- 8 March 1968: First SR-71A (#61-7978) arrives at Kadena AB to replace A-12s.

- 21 March 1968: First SR-71 (#61-7976) operational mission flown from Kadena AB over Vietnam.

- 8 May 1968: Jack Layton flies last operational A-12 sortie, over North Korea.

- 5 June 1968: Loss of last A-12 (#60–6932) during Functional Checkout Flight (FCF) flown from Kadena, Jack W. Weeks became the second and last CIA pilot killed in the line of duty during Oxcart and is so honored in the "Book of Honor" at CIA Headquarters. The A-12 had a radio telemetry system called "Birdwatcher", monitoring the most critical aircraft systems and transmitting data to ground monitoring stations. Following aerial refueling, the ground station was informed via "Birdwatcher" that the starboard engine exhaust gas temperature was in excess of 1,580 °F (860 °C), the fuel flow on that engine was less than 7,500 lb (3,400 kg) per hour and that the aircraft was below 68,500 feet (20,900 metres). Several attempts to make contact were made without success. Monitoring continued until the time that the aircraft's fuel would have been depleted. The aircraft was declared missing 520 miles (840 kilometres) east of the Philippines and 625 miles (1,006 kilometres) south of Okinawa in the South China Sea. The loss was due to an in-flight emergency. To maintain security the official news release identified the loss as an SR-71. An intense air and sea search was conducted but no wreckage of "Article 129" was ever recovered. It was presumed totally destroyed at sea. The "Birdwatcher" system provided the only clues to what happened and was the basis for the accident report. It was ascertained that a malfunction involving an engine over-temperature and low fuel flow on the starboard engine had contributed to a catastrophic failure and subsequent aircraft break-up.[57][61][62]

- 21 June 1968: Final A-12 flight to Palmdale, California.

See SR-71 timeline for later SR-71 events.

Variants

Training variant

The A-12 training variant (60-6927 "Titanium Goose") was a two-seat model with two cockpits in tandem with the rear cockpit raised and slightly offset. In case of emergency, the trainer was designed to allow the flight instructor to take control.[22][63]

YF-12A

The YF-12 program was a limited production variant of the A-12. Lockheed convinced the U.S. Air Force that an aircraft based on the A-12 would provide a less costly alternative to the recently canceled North American Aviation XF-108, since much of the design and development work on the YF-12 had already been done and paid for. Thus, in 1960 the Air Force agreed to take the seventh to ninth slots on the A-12 production line and have them completed in the YF-12A interceptor configuration.[64]

M-21

The M-21, a two-seat variant, carried and launched the Lockheed D-21, an unmanned, faster and higher-flying reconnaissance drone. The M-21 had a pylon on its back for mounting the drone and a second cockpit for a Launch Control Operator/Officer (LCO) in the place of the A-12's Q bay.[65] The D-21 was autonomous; after launch, it would fly over the target, travel to a predetermined rendezvous point, eject its data package, and self-destruct. A C-130 Hercules would catch the package in midair.[66]

The M-21 program was canceled in 1966 after a drone collided with the mother ship at launch. The crew safely ejected, but LCO Ray Torick drowned when he landed in the ocean and his flight suit filled with water.[67][68][69][70][71]

The D-21 lived on in the form of a B-model launched from a pylon under the wing of the B-52 bomber. The D-21B performed operational missions over China from 1969 to 1971.[72]

| Serial number | Article | Model | Flights | Hours | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60-6924 | 121 | A-12 | 322 | 418.2 | On display |

| 60-6925 | 122 | A-12 | 161 | 177.9 | On display |

| 60-6926 | 123 | A-12 | 79 | 135.3 | Lost |

| 60-6927 | 124 | A-12 trainer | 614 | 1076.4 | On display |

| 60-6928 | 125 | A-12 | 202 | 334.9 | Lost |

| 60-6929 | 126 | A-12 | 105 | 169.2 | Lost |

| 60-6930 | 127 | A-12 | 258 | 499.2 | On display |

| 60-6931 | 128 | A-12 | 232 | 453.0 | On display |

| 60-6932 | 129 | A-12 | 268 | 409.9 | Lost |

| 60-6933 | 130 | A-12 | 217 | 406.3 | On display |

| 60-6937 | 131 | A-12 | 177 | 345.8 | On display |

| 60-6938 | 132 | A-12 | 197 | 369.9 | On display |

| 60-6939 | 133 | A-12 | 10 | 8.3 | Lost |

| 60-6940 | 134 | M-21 | 80 | 123.9 | On display |

| 60-6941 | 135 | M-21 | 95 | 152.7 | Lost |

Accidents and incidents

Six of the 15 A-12s were lost in accidents, with the loss of two pilots and an engineer:

- 24 May 1963: 60-6926 (Article 123) crashed near Wendover, Utah.[73][74] The aircraft was flying a subsonic engine test flight when it entered a cloud, pitched up, and went out of control; the CIA pilot ejected successfully.[75] The investigation found that cloud vapor had formed ice in the pitot tube, causing the airspeed indicator to show an erroneous reading. The aircraft pitched up sharply and entered an unrecoverable stall.[75] The pilot was wearing a standard flight suit for this low-altitude flight, and did not look suspicious to the truck driver that recovered him or the highway patrol office where he was taken. The press were told that a Republic F-105 Thunderchief had crashed.[75]

- 9 July 1964: 60-6939 (Article 133) was lost on approach to Groom Dry Lake due to a complete hydraulic failure.[73]

- 30 July 1966: 60-6941 (Article 135), one of the two drone carriers, was lost during a test flight off the California coast. The pilot and launch control engineer ejected safely but the engineer drowned.[73] Article 135 was operating 300 miles from the California coast to carry out a test launch of a D-21. The aircraft was flying at Mach 3.2+ when the crew made sure that Marquardt engine on the D-21 had the required airflow.[76] The drone was launched but the D-21 engine failed to start and it slammed down on the launch pylon causing the mother ship to pitch up.[76] The pressure from the Mach-3.2 airflow "ripped the fuselage forebody from the wing planform". The crew were unable to escape at this high speed but managed to eject as the forebody tumbled towards the sea.[76] The pilot was picked up by helicopter from the sea but the LCO drowned.[76]

- 5 January 1967: 60-6928 (Article 125) was lost during a training flight. The pilot ejected but failed to separate from his seat and was killed.[73] Due to a faulty fuel gauge, Article 125 ran out of fuel 70 miles from Groom Dry Lake. The pilot glided to a lower altitude to perform a controlled bailout but could not separate his parachute from his ejection seat. He was the first Cygnus pilot to be killed in an A-12 accident.[77]

- 28 December 1967: 60-6929 (Article 126) was lost on take-off from Groom Lake due to incorrect installation of the Stability Augmentation System (SAS).[73]

- 5 June 1968: 60-6932 (Article 129) was lost off the Philippines during a functional check flight. The pilot was killed.[73]

Aircraft on display

All nine surviving aircraft are on display in the U.S.:

- A-12 60-6924 at the Air Force Flight Test Center Museum Annex, Blackbird Airpark, at Plant 42, Palmdale, California.

- A-12 60-6925 at the Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum, parked on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid, New York City.

- A-12 60-6927, the two-seat trainer, at the California Science Center in Los Angeles, California.[78]

- A-12 60-6930 at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, Huntsville, Alabama.

- A-12 60-6931 at CIA headquarters, Langley, Virginia.[N 1]

- A-12 60-6933 at the San Diego Air & Space Museum, Balboa Park, San Diego, California.

- A-12 60-6937 at the Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham, Alabama.

- A-12 60-6938 at Battleship Memorial Park (USS Alabama), Mobile, Alabama.

- M-21 60-6940 at the Museum of Flight, Seattle, Washington.

![]() Media related to Lockheed A-12 museum aircraft at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lockheed A-12 museum aircraft at Wikimedia Commons

Specifications (A-12)

Data from A-12 Utility Flight Manual[79]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 101 ft 7 in (30.96 m)

- Wingspan: 55 ft 7 in (16.94 m)

- Height: 18 ft 6 in (5.64 m)

- Wing area: 1,795 sq ft (166.8 m2)

- Max takeoff weight: 117,000 lb (53,070 kg)

- max landing weight:52,000 lb (24,000 kg)

- Payload: 2,500 lb (1,100 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 10,590 US gal (40,100 l; 8,820 imp gal) of JP-7 (68,300 lb (31,000 kg) at 6.45 lb/USgal)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney JT11D-20B (J58-1) After-burning turbojet / ramjet, 20,500 lbf (91 kN) thrust each dry, 32,500 lbf (145 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 3.35

- Range: 1,350 nmi; 1,553 mi (2,500 km)

- Service ceiling: 95,000 ft (29,000 m) +

- Rate of climb: 11,800 ft/min (60 m/s)

- Wing loading: 65 lb/sq ft (320 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.56 lbf/lb (0.0011 kN/kg)

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ "Article 128", unveiled on Wednesday, 19 September 2007, at CIA Headquarters in Langley, Virginia. On hand was Ken Collins, a retired Air Force Colonel, one of only six pilots to fly the A-12s.

Citations

- ↑ Robarge, David. "Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft - From Drawing Board to Factory Floor". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ Mclninch 1996, title page.

- ↑ Robarge, David. "ARCHANGEL: CIA's SUPERSONIC A-12 RECONNAISSANCE AIRCRAFT Second Edition 2012" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Page 15.

- ↑ Crickmore 2000, p. 16

- ↑ "The U-2's Intended Successor: Project Oxcart 1956–1968". Central Intelligence Agency, approved for release by the CIA in October 1994. Retrieved: 26 January 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Mclninch, Thomas P. "The Oxcart Story — Central Intelligence Agency". CIA HISTORICAL REVIEW PROGRAM 2 JULY 96.

- ↑ Robarge 2008, p. 6.

- ↑ Robarge, David. "Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Recconaissance Aircraft Second Edition 2012" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Page 21.

- ↑ Rich, Ben R.; Janos, Leo (1994). Skunk Works : a personal memoir of my years at Lockheed (1st pbk. ed.). New York, NY: Back Bay Books. ISBN 9780316743006.

- ↑ Graham, Richard (1 November 2015). The Complete Book of the SR-71 Blackbird: The Illustrated Profile of Every Aircraft, Crew, and Breakthrough of the World's Fastest Stealth Jet. Zenith Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780760348499. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ↑ Remak, Jeannette (2015). "A Technical Directive The Lockheed A-12 Blackbird in Captivity The Care and Feeding of a Historical Treasure". RoadrunnersInternationale.com. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ↑ "Facts You Didn't Know About the SR-71 Blackbird". iliketowastemytime.com.

- ↑ Jacobsen 2011, p. 51.

- ↑ Robarge 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Robarge 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 16–17.

- 1 2 Lacitis, Erik. "Area 51 vets break silence: Sorry, but no space aliens or UFOs." The Seattle Times, 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Robarge 2008, p. 22, 23.

- 1 2 Jacobsen, Annie. "The Road to Area 51." Los Angeles Times, 5 April 2009.

- ↑ "SR-71 Blackbird." Lockheed Martin. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ↑ Landis and Jenkins 2005, p. 16.

- 1 2 Robarge, David. "Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft - Full Stress Testing". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ McIninch, Thomas P. "STUDIES IN INTELLIGENCE VOL 26 NO 2 SUMMER 1982 - THE OXCART STORY (Blackbirds History)". Central Intelligence Agency document on blackbirds.net.

- ↑ "SUMMARY REPORT OF MAJOR AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT RESULTING IN THE LOSS OF A-12 NUMBER 126" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Doc Number 0001472027.

- 1 2 Robarge, David. "Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft - Finding a Mission". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "LOSS OF ARTICLE 125 (OXCART AIRCRAFT)" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number 0001473843.

- ↑ McIninch 1996, p. 19.

- ↑ McIninch 1996, p. 20.

- ↑ McIninch 1996, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Kopp, Dr Carlo (April 2012). "SNR-75 Fan Song E Engagement Radar / Станция Наведения Ракет СНР-75 Fan Song E". Air Power Australia.

- ↑ "Pieces of History: Missile Debris from A-12 OXCART". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Kopp, Dr Carlo. "Almaz 5V21/28 / S-200VE Vega Long Range Air Defence System / SA-5 Gammon Зенитный Ракетный Комплекс 5В21/28 / С-200ВЭ 'Вега'". Air Power Australia. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ↑ "BLACK SHIELD RECONNAISSANCE MISSIONS 1 JANUARY - 31 MARCH 1968" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number 0001472531 page 16.

- ↑ "PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF BLACK SHIELD MISSION 6847 OVER NORTH KOREA" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number: 0001474986.

- ↑ Mclninch, Thomas P. "The Oxcart Story". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "BLACK SHIELD RECONNAISSANCE MISSIONS 1 JANUARY - 31 MARCH 1968" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number 0001472531 Page 14.

- ↑ "The Oxcart Story", CIA, p. 267

- ↑ McIninch 1996, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Robarge, David. "A Futile Fight for Survival. Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft." U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, Center for the Study of Intelligence, CSI Publications, 27 June 2007. Retrieved: 13 April 2009.

- ↑ "OXCART/SR-71 INFORMATION FOR EXCOM MEETING" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number: 0001472041.

- ↑ Robarge, David. "Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft - The OXCART "Family"". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "CRITIQUE FOR OXCART MISSION NUMBER BX6858" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number 0001472531.

- ↑ McIninch 1996, p. 33.

- ↑ Robarge 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ McIninch 1996, p. 34.

- ↑ Hayden, General Michael V. "General Hayden's Remarks at A-12 Presentation Ceremony." Central Intelligence Agency, Remarks of Director of the Central Intelligence Agency at the A-12 Presentation Ceremony, 19 September 2007. Retrieved: 10 April 2009.

- ↑ Karp, Jonathan. "Stealthy Maneuver: The CIA Captures An A-12 Blackbird". The Wall Street Journal, A1, 26 January 2007. Retrieved: 10 April 2009.

- ↑ Taylor, Dino A. Brugioni ; edited by Doris G. (2010). Eyes in the sky : Eisenhower, the CIA, and Cold War aerial espionage ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. p. 196. ISBN 9781591140825.

- ↑ Crickmore, Paul F. (2004). Lockheed Blackbird : beyond the secret missions (Rev. ed.). Oxford: Osprey. p. 26. ISBN 1841766941.

- ↑ Hehs, Eric. "Code One Magazine: Super Hustler, FISH, Kingfish, And Beyond (Part 2: FISH)". Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company.

- ↑ Richelson, Jeffrey T. (2002). The wizards of Langley : inside the CIA's Directorate of Science and Technology. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. p. 21. ISBN 0813340594.

- ↑ III, L. Parker Temple, (2004). Shades of gray : national security and the evolution of space reconnaissance. Reston, Va.: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. p. 112. ISBN 1563477238.

- ↑ "CIA, Debriefing of Francis Gary Powers, February 13, 1962, Top Secret, 31 pp" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency National Archives.

- ↑ Robarge, David. "Breaking Through Technological Barriers". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ "First flight of the A-12 at Groom Lake narrated by its pilot, Lockheed test pilot Lou Schalk". Nevada Aerospace Hall of Fame on YouTube.

- ↑ Hildebrant, Don. "Timeline of the SR-71" (PDF). (Page 7) Roadrunners Internationale Declassified U-2 A-12 Projects Aquatone OXCART Area 51.

- 1 2 Robarge, David. "ARCHANGEL: CIA's SUPERSONIC A-12 RECONNAISSANCE AIRCRAFT Second Edition 2012" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Page 52.

- ↑ "COMPARISON OF SR-71 TO A-12 AIRCRAFT" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number 0001471952.

- ↑ "COMPARISON OF THE CAPABILITIES, PERFORMANCE, COUNTERMEASURES SYSTEMS AND OPERATIONAL STATUS OF THE A-12 AND SR-71" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency Document Number 0001472042.

- ↑ Jacobsen 2011, p. 273.

- ↑ "CIA Pilot Jack Weeks remembered by family and members". Roadrunners Internationale Declassified U-2 A-12 Projects Aquatone OXCART Area 51.

- ↑ "Tribute to Jack W. Weeks, CIA A-12 Project Pilot for Operation Black Shield". Roadrunners Internationale Declassified U-2 A-12 Projects Aquatone OXCART Area 51.

- ↑ Robarge, David. "Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft - Breaking Through Technological Barriers". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Landis and Jenkins 2005, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Donald 2003, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ MD-21 crash footage. YouTube. Retrieved: 13 October 2010.

- ↑ Lockheed A-12 & SR-71 Ejections Retrieved: 29 August 2016.

- ↑ Richard H. Graham, SR-71: The Complete Illustrated History of the Blackbird, The World's Highest, Fastest Plane, p.39

- ↑ Paul F Crickmore, Lockheed SR-71 Operations in the Far East

- ↑ Richard H. Graham, SR-71 Revealed: The Untold Story, p.42

- ↑ Donald 2003, pp. 155–156.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Crickmore 2000, pp. 236-237

- ↑ http://archive.sltrib.com/story.php?ref=/sltrib/news/51976355-78/collins-plane-area-crash.html.csp

- 1 2 3 Crickmore 2000, pp. 19-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Crickmore 2000, p. 38

- ↑ Crickmore 2000, p. 24

- ↑ "A-12 Blackbird". Los Angeles, CA: California Science Center. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ↑ "1". A-12 Utility Flight Manual (pdf). Central Intelligence Agency. 15 September 1965. p. 1. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

Bibliography

- Donald, David, ed. "Lockheed's Blackbirds: A-12, YF-12 and SR-71". Black Jets. Norwalk, Connecticut: AIRtime, 2003. ISBN 1-880588-67-6.

- Jacobsen, Annie. Area 51. London: Orion Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4091-4113-6.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Lockheed Secret Projects: Inside the Skunk Works. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7603-0914-8.

- Landis, Tony R. and Dennis R. Jenkins. Lockheed Blackbirds. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Specialty Press, revised edition, 2005. ISBN 1-58007-086-8.

- McIninch, Thomas. "The Oxcart Story." Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, 2 July 1996. Retrieved: 10 April 2009.

- Pace, Steve. Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird. Swindon, UK: The Crowood Press, 2004. ISBN 1-86126-697-9.

- Robarge, David. Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 2008. ISBN 1-92966-716-7.

Additional sources

- Crickmore, Paul F. Lockheed SR-71 - The Secret Missions Exposed. Oxford, England: Osprey Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1 84176 098 6.

- Graham, Richard H. SR-71 Revealed: The Inside Story. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 1996. ISBN 978-0-7603-0122-7.

- Johnson, Clarence L. "History of the OXCART Program." Burbank, California: Lockheed Aircraft Corporation Advanced Development Projects, SP-1362, 1 July 1968.

- Johnson, C.L. Kelly: More Than My Share of it All. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1985. ISBN 0-87474-491-1.

- Lovick, Edward, Jr. Radar Man: A Personal History of Stealth. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4502-4802-0.

- Merlin, Peter W. Design and Development of the Blackbird: Challenges and Lessons Learned., Orlando, Florida: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 2009. AIAA 2009-1522.

- Merlin, Peter W. From Archangel to Senior Crown: Design and Development of the Blackbird (Library of Flight Series). Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 2008. ISBN 978-1-56347-933-5.

- Pedlow, Gregory W. and Donald E. Welzenbach. The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance: The U-2 and OXCART Programs, 1954–1974. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 1992. ISBN 0-7881-8326-5.

- Rich, Ben R. and Leo Janos. Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My years at Lockheed. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1994. ISBN 978-0-316-74330-3.

- Shul, Brian and Sheila Kathleen O'Grady. Sled Driver: Flying the World's Fastest Jet. Marysville, California: Gallery One, 1994. ISBN 0-929823-08-7.

- Suhler, Paul A. From RAINBOW to GUSTO: Stealth and the Design of the Lockheed Blackbird (Library of Flight Series). Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 2009. ISBN 978-1-60086-712-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lockheed A-12. |

- Archangel: CIA's Supersonic A-12 Reconnaissance Aircraft by David Robarge. (Cia.gov)

- Project Oxcart: CIA Report

- FOIA documents on OXCART (Declassified 21 January 2008)

- Differences between the A-12 and SR-71

- Blackbird Spotting maps the location of every existing Blackbird, with aerial photos from Google Maps

- Photographs and disposition of the "Habu" aircraft at habu.org

- The U-2's Intended Successor: Project Oxcart (Chapter 6 of "The CIA and Overhead Reconnaissance", by Pedlow & Welzenbach)

- USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers for 1960, including all A-12s, YF-12As and M-21s

- "The Real X-Jet", Air & Space magazine, March 1999

- Secret A-12 Spy Plane Officially Unveiled at CIA's Headquarters

- US Secret Spy Planes Project-1963 Test Flight Crash