Project management

Project management is the discipline of initiating, planning, executing, controlling, and closing the work of a team to achieve specific goals and meet specific success criteria. A project is a temporary endeavor designed to produce a unique product, service or result with a defined beginning and end (usually time-constrained, and often constrained by funding or deliverable) undertaken to meet unique goals and objectives, typically to bring about beneficial change or added value.[1][2] The temporary nature of projects stands in contrast with business as usual (or operations),[3] which are repetitive, permanent, or semi-permanent functional activities to produce products or services. In practice, the management of such distinct production approaches requires the development of distinct technical skills and management strategies.[4]

The primary challenge of project management is to achieve all of the project goals within the given constraints.[5] This information is usually described in project documentation, created at the beginning of the development process. The primary constraints are scope, time, quality and budget.[6] The secondary — and more ambitious — challenge is to optimize the allocation of necessary inputs and apply them to meet pre-defined objectives.

History

Until 1900, civil engineering projects were generally managed by creative architects, engineers, and master builders themselves, for example, Vitruvius (first century BC), Christopher Wren (1632–1723), Thomas Telford (1757–1834) and Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859).[7] In the 1950s organizations started to systematically apply project-management tools and techniques to complex engineering projects.[8]

As a discipline, project management developed from several fields of application including civil construction, engineering, and heavy defense activity.[9] Two forefathers of project management are Henry Gantt, called the father of planning and control techniques,[10] who is famous for his use of the Gantt chart as a project management tool (alternatively Harmonogram first proposed by Karol Adamiecki[11]); and Henri Fayol for his creation of the five management functions that form the foundation of the body of knowledge associated with project and program management.[12] Both Gantt and Fayol were students of Frederick Winslow Taylor's theories of scientific management. His work is the forerunner to modern project management tools including work breakdown structure (WBS) and resource allocation.

The 1950s marked the beginning of the modern project management era where core engineering fields come together to work as one. Project management became recognized as a distinct discipline arising from the management discipline with engineering model.[13] In the United States, prior to the 1950s, projects were managed on an ad-hoc basis, using mostly Gantt charts and informal techniques and tools. At that time, two mathematical project-scheduling models were developed. The "critical path method" (CPM) was developed as a joint venture between DuPont Corporation and Remington Rand Corporation for managing plant maintenance projects. The "program evaluation and review technique" (PERT), was developed by the U.S. Navy Special Projects Office in conjunction with the Lockheed Corporation and Booz Allen Hamilton as part of the Polaris missile submarine program.[14]

PERT and CPM are very similar in their approach but still present some differences. CPM is used for projects that assume deterministic activity times; the times at which each activity will be carried out are known. PERT, on the other hand, allows for stochastic activity times; the times at which each activity will be carried out are uncertain or varied. Because of this core difference, CPM and PERT are used in different contexts. These mathematical techniques quickly spread into many private enterprises.

At the same time, as project-scheduling models were being developed, technology for project cost estimating, cost management and engineering economics was evolving, with pioneering work by Hans Lang and others. In 1956, the American Association of Cost Engineers (now AACE International; the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering) was formed by early practitioners of project management and the associated specialties of planning and scheduling, cost estimating, and cost/schedule control (project control). AACE continued its pioneering work and in 2006 released the first integrated process for portfolio, program and project management (total cost management framework).

In 1969, the Project Management Institute (PMI) was formed in the USA.[15] PMI publishes A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), which describes project management practices that are common to "most projects, most of the time." PMI also offers a range of certifications.

The 4 P's of project management

Recent studies point to the four P's of project management; together, these "4 P's" suffice to describe the culture that exists within project teams: 1) P for Plan: this refers to all activities that involve planning and forecasting. At this stage, the project and/or elements of the projects have not materialized yet; 2) P for Processes : as well documented in the PMBOK (Project Management Book of Knowledge), projects consist largely of a series of predetermined and well-structured processes; 3) P for People: People are an essential component of the project's dynamics and a number of studies show that people are at the heart of some projects' endemic problems. In particular, the so-called "dreadful combination" refers to a mixture of poor planning and inadequate people; finally, 4), P for Power which describes all lines of authority, decision-makers, organigrams, policies for implementation and the likes[16]

Approaches

There are a number of approaches to organizing and completing project activities, including: phased, lean, iterative, and incremental. There are also several extensions to project planning based, for example, on outcomes (product-based) or activities (process-based).

Regardless of the methodology employed, careful consideration must be given to the overall project objectives, timeline, and cost, as well as the roles and responsibilities of all participants and stakeholders.

Phased approach

The phased (or staged) approach breaks down and manages the work through a series of distinct steps to be completed, and is often referred to as "traditional"[17] or "waterfall"[18]. Although it can vary, it typically consists of five process areas, four phases plus control:

.png)

- initiation

- planning and design

- construction

- monitoring and controlling

- completion or closing

Many industries use variations of these project stages and it is not uncommon for the stages to be renamed in order to better suit the organization. For example, when working on a brick-and-mortar design and construction, projects will typically progress through stages like pre-planning, conceptual design, schematic design, design development, construction drawings (or contract documents), and construction administration.

While the phased approach works well for small, well-defined projects, it often results in challenge or failure on larger projects, or those that are more complex or have more ambiguities and risk.[19]

Lean project management

Lean project management uses the principles from lean manufacturing to focus on delivering value with less waste and reduced time.

Iterative and incremental project management

In critical studies of project management it has been noted that phased approaches are not well suited for projects which are large-scale and multi-company[20], with undefined, ambiguous, or fast-changing requirements[21], or those with high degrees of risk, dependency, and fast-changing technologies[22]. The cone of uncertainty explains some of this as the planning made on the initial phase of the project suffers from a high degree of uncertainty. This becomes especially true as software development is often the realization of a new or novel product.

These complexities are better handled with a more exploratory or iterative and incremental approach.[23] Several models of iterative and incremental project management have evolved, including agile project management, dynamic systems development method, extreme project management, and Innovation Engineering®[24].

Critical chain project management

Critical chain project management (CCPM) is an application of the theory of constraints (TOC) to planning and managing projects, and is designed to deal with the uncertainties inherent in managing projects, while taking into consideration limited availability of resources (physical, human skills, as well as management & support capacity) needed to execute projects.

The goal is to increase the flow of projects in an organization (throughput). Applying the first three of the five focusing steps of TOC, the system constraint for all projects, as well as the resources, are identified. To exploit the constraint, tasks on the critical chain are given priority over all other activities. Finally, projects are planned and managed to ensure that the resources are ready when the critical chain tasks must start, subordinating all other resources to the critical chain.

Product-based planning

Product-based planning is a structured approach to project management, based on identifying all of the products (project deliverables) that contribute to achieving the project objectives. As such, it defines a successful project as output-oriented rather than activity- or task-oriented.[25] The most common implementation of this approach is PRINCE2.[26]

Process-based management

The incorporation of process-based management has been driven by the use of maturity models such as the OPM3 and the CMMI (capability maturity model integration; see this example of a predecessor) and ISO/IEC15504 (SPICE – software process improvement and capability estimation). Unlike SEI's CMM, the OPM3 maturity model describes how to make project management processes capable of performing successfully, consistently, and predictably in order to enact the strategies of an organization.

Project production management

Project production management is the application of operations management to the delivery of capital projects. The Project production management framework is based on a project as a production system view, in which a project transforms inputs (raw materials, information, labor, plant & machinery) into outputs (goods and services).[27]

Benefits realization management

Benefits realization management (BRM) enhances normal project management techniques through a focus on outcomes (the benefits) of a project rather than products or outputs, and then measuring the degree to which that is happening to keep a project on track. This can help to reduce the risk of a completed project being a failure by delivering agreed upon requirements/outputs but failing to deliver the benefits of those requirements.

In addition, BRM practices aim to ensure the alignment between project outcomes and business strategies. The effectiveness of these practices is supported by recent research evidencing BRM practices influencing project success from a strategic perspective across different countries and industries.[28]

An example of delivering a project to requirements might be agreeing to deliver a computer system that will process staff data and manage payroll, holiday and staff personnel records. Under BRM the agreement might be to achieve a specified reduction in staff hours required to process and maintain staff data.

Earned value management

Earned value management (EVM) extends project management with techniques to improve project monitoring. It illustrates project progress towards completion in terms of work and value (cost).

Process groups

Traditionally (depending on what project management methodology is being used), project management includes a number of elements: four to five project management process groups, and a control system. Regardless of the methodology or terminology used, the same basic project management processes or stages of development will be used. Major process groups generally include:[6]

- Initiation

- Planning

- Production or execution

- Monitoring and controlling

- Closing

In project environments with a significant exploratory element (e.g., research and development), these stages may be supplemented with decision points (go/no go decisions) at which the project's continuation is debated and decided. An example is the Phase–gate model.

Initiating

The initiating processes determine the nature and scope of the project.[30] If this stage is not performed well, it is unlikely that the project will be successful in meeting the business’ needs. The key project controls needed here are an understanding of the business environment and making sure that all necessary controls are incorporated into the project. Any deficiencies should be reported and a recommendation should be made to fix them.

The initiating stage should include a plan that encompasses the following areas:

- analyzing the business needs/requirements in measurable goals

- reviewing of the current operations

- financial analysis of the costs and benefits including a budget

- stakeholder analysis, including users, and support personnel for the project

- project charter including costs, tasks, deliverables, and schedules

- SWOT analysis strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to the business

Planning

After the initiation stage, the project is planned to an appropriate level of detail (see example of a flow-chart).[29] The main purpose is to plan time, cost and resources adequately to estimate the work needed and to effectively manage risk during project execution. As with the Initiation process group, a failure to adequately plan greatly reduces the project's chances of successfully accomplishing its goals.

Project planning generally consists of[31]

- determining how to plan (e.g. by level of detail or Rolling Wave planning);

- developing the scope statement;

- selecting the planning team;

- identifying deliverables and creating the work breakdown structure;

- identifying the activities needed to complete those deliverables and networking the activities in their logical sequence;

- estimating the resource requirements for the activities;

- estimating time and cost for activities;

- developing the schedule;

- developing the budget;

- risk planning;

- developing quality assurance measures;

- gaining formal approval to begin work.

Additional processes, such as planning for communications and for scope management, identifying roles and responsibilities, determining what to purchase for the project and holding a kick-off meeting are also generally advisable.

For new product development projects, conceptual design of the operation of the final product may be performed concurrent with the project planning activities, and may help to inform the planning team when identifying deliverables and planning activities.

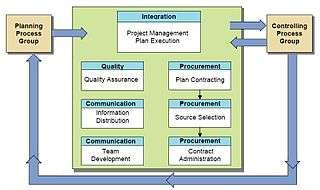

Executing

While executing we must know what are the planned terms that need to be executed. The execution/implementation phase ensures that the project management plan's deliverables are executed accordingly. This phase involves proper allocation, co-ordination and management of human resources and any other resources such as material and budgets. The output of this phase is the project deliverables.

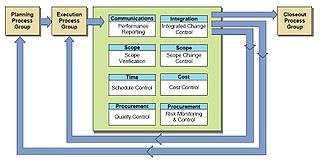

Monitoring and controlling

Monitoring and controlling consists of those processes performed to observe project execution so that potential problems can be identified in a timely manner and corrective action can be taken, when necessary, to control the execution of the project. The key benefit is that project performance is observed and measured regularly to identify variances from the project management plan..

Monitoring and controlling includes:[32]

- Measuring the ongoing project activities ('where we are');

- Monitoring the project variables (cost, effort, scope, etc.) against the project management plan and the project performance baseline (where we should be);

- Identifying corrective actions to address issues and risks properly (How can we get on track again);

- Influencing the factors that could circumvent integrated change control so only approved changes are implemented.

In multi-phase projects, the monitoring and control process also provides feedback between project phases, in order to implement corrective or preventive actions to bring the project into compliance with the project management plan.

Project maintenance is an ongoing process, and it includes:[6]

- Continuing support of end-users

- Correction of errors

- Updates to the product over time

.png)

In this stage, auditors should pay attention to how effectively and quickly user problems are resolved.

Over the course of any construction project, the work scope may change. Change is a normal and expected part of the construction process. Changes can be the result of necessary design modifications, differing site conditions, material availability, contractor-requested changes, value engineering and impacts from third parties, to name a few. Beyond executing the change in the field, the change normally needs to be documented to show what was actually constructed. This is referred to as change management. Hence, the owner usually requires a final record to show all changes or, more specifically, any change that modifies the tangible portions of the finished work. The record is made on the contract documents – usually, but not necessarily limited to, the design drawings. The end product of this effort is what the industry terms as-built drawings, or more simply, "as built." The requirement for providing them is a norm in construction contracts. Construction document management is a highly important task undertaken with the aid an online or desktop software system, or maintained through physical documentation. The increasing legality pertaining to the construction industries maintenance of correct documentation has caused the increase in the need for document management systems.

When changes are introduced to the project, the viability of the project has to be re-assessed. It is important not to lose sight of the initial goals and targets of the projects. When the changes accumulate, the forecasted result may not justify the original proposed investment in the project. Successful project management identifies these components, and tracks and monitors progress so as to stay within time and budget frames already outlined at the commencement of the project.

Closing

Closing includes the formal acceptance of the project and the ending thereof. Administrative activities include the archiving of the files and documenting lessons learned.

This phase consists of:[6]

- Contract closure: Complete and settle each contract (including the resolution of any open items) and close each contract applicable to the project or project phase.

- Project close: Finalize all activities across all of the process groups to formally close the project or a project phase

Also included in this phase is the Post Implementation Review. This is a vital phase of the project for the project team to learn from experiences and apply to future projects. Normally a Post Implementation Review consists of looking at things that went well and analyzing things that went badly on the project to come up with lessons learned.

Project controlling and project control systems

Project controlling (also known as Cost Engineering) should be established as an independent function in project management. It implements verification and controlling function during the processing of a project in order to reinforce the defined performance and formal goals.[33] The tasks of project controlling are also:

- the creation of infrastructure for the supply of the right information and its update

- the establishment of a way to communicate disparities of project parameters

- the development of project information technology based on an intranet or the determination of a project key performance indicator system (KPI)

- divergence analyses and generation of proposals for potential project regulations[34]

- the establishment of methods to accomplish an appropriate project structure, project workflow organization, project control and governance

- creation of transparency among the project parameters[35]

Fulfillment and implementation of these tasks can be achieved by applying specific methods and instruments of project controlling. The following methods of project controlling can be applied:

- investment analysis

- cost–benefit analysis

- value benefit analysis

- expert surveys

- simulation calculations

- risk-profile analysis

- surcharge calculations

- milestone trend analysis

- cost trend analysis

- target/actual-comparison[36]

Project control is that element of a project that keeps it on track, on-time and within budget.[32] Project control begins early in the project with planning and ends late in the project with post-implementation review, having a thorough involvement of each step in the process. Projects may be audited or reviewed while the project is in progress. Formal audits are generally risk or compliance-based and management will direct the objectives of the audit. An examination may include a comparison of approved project management processes with how the project is actually being managed.[37] Each project should be assessed for the appropriate level of control needed: too much control is too time consuming, too little control is very risky. If project control is not implemented correctly, the cost to the business should be clarified in terms of errors and fixes.

Control systems are needed for cost, risk, quality, communication, time, change, procurement, and human resources. In addition, auditors should consider how important the projects are to the financial statements, how reliant the stakeholders are on controls, and how many controls exist. Auditors should review the development process and procedures for how they are implemented. The process of development and the quality of the final product may also be assessed if needed or requested. A business may want the auditing firm to be involved throughout the process to catch problems earlier on so that they can be fixed more easily. An auditor can serve as a controls consultant as part of the development team or as an independent auditor as part of an audit.

Businesses sometimes use formal systems development processes. These help assure systems are developed successfully. A formal process is more effective in creating strong controls, and auditors should review this process to confirm that it is well designed and is followed in practice. A good formal systems development plan outlines:

- A strategy to align development with the organization's broader objectives

- Standards for new systems

- Project management policies for timing and budgeting

- Procedures describing the process

- Evaluation of quality of change

Topics

Project managers

A project manager is a professional in the field of project management. Project managers can have the responsibility of the planning, execution, controlling, and closing of any project typically relating to the construction industry, engineering, architecture, computing, and telecommunications. Many other fields of production engineering, design engineering, and heavy industrial have project managers.

A project manager is the person accountable for accomplishing the stated project objectives. Key project management responsibilities include creating clear and attainable project objectives, building the project requirements, and managing the triple constraint (now including more constraints and calling it competing constraints) for projects, which is cost, time, and scope for the first three but about three additional ones in current project management.

A project manager is often a client representative and has to determine and implement the exact needs of the client, based on knowledge of the firm they are representing. The ability to adapt to the various internal procedures of the contracting party, and to form close links with the nominated representatives, is essential in ensuring that the key issues of cost, time, quality and above all, client satisfaction, can be realized.

Project management types

Project management can apply to any project, but it is often tailored to accommodate the specific needs of different and highly specialized industries. For example, the construction industry, which focuses on the delivery of things like buildings, roads, and bridges, has developed its own specialized form of project management that it refers to as construction project management and in which project managers can become trained and certified.[38] The information technology industry has also evolved to develop its own form of project management that is referred to as IT project management and which specializes in the delivery of technical assets and services that are required to pass through various lifecycle phases such as planning, design, development, testing, and deployment. Biotechnology project management focuses on the intricacies of biotechnology research and development.[39]

For each type of project management, project managers develop and utilize repeatable templates that are specific to the industry they're dealing with. This allows project plans to become very thorough and highly repeatable, with the specific intent to increase quality, lower delivery costs, and lower time to deliver project results.

Risk management

The United States Department of Defense states; "Cost, Schedule, Performance, and Risk," are the four elements through which Department of Defense acquisition professionals make trade-offs and track program status.[40] There are also international standards. Risk management applies proactive identification (see tools) of future problems and understanding of their consequences allowing predictive decisions about projects.

Work breakdown structure

The work breakdown structure (WBS) is a tree structure that shows a subdivision of effort required to achieve an objective—for example a program, project, and contract. The WBS may be hardware-, product-, service-, or process-oriented (see an example in a NASA reporting structure (2001)).[41]

A WBS can be developed by starting with the end objective and successively subdividing it into manageable components in terms of size, duration, and responsibility (e.g., systems, subsystems, components, tasks, sub-tasks, and work packages), which include all steps necessary to achieve the objective.[19]

The work breakdown structure provides a common framework for the natural development of the overall planning and control of a contract and is the basis for dividing work into definable increments from which the statement of work can be developed and technical, schedule, cost, and labor hour reporting can be established.[41] The work breakdown structure can be displayed in two forms, as a table with subdivision of tasks or as an organisational chart whose lowest nodes are referred to as "work packages".

It is an essential element in assessing the quality of a plan.

International standards

There have been several attempts to develop project management standards, such as:

- ISO 21500: 2012 – Guidance on project management. This is the first project management ISO.

- ISO 31000: 2009 – Risk management. Risk management is 1 of the 10 knowledge areas of either ISO 21500 or PMBoK5 concept of project management.

- ISO/IEC/IEEE 16326-2009 – Systems and Software Engineering—Life Cycle Processes—Project Management[42]

- Capability Maturity Model from the Software Engineering Institute.

- GAPPS, Global Alliance for Project Performance Standards – an open source standard describing COMPETENCIES for project and program managers.

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge from the Project Management Institute (PMI)

- HERMES method, Swiss general project management method, selected for use in Luxembourg and international organizations.

- The ISO standards ISO 9000, a family of standards for quality management systems, and the ISO 10006:2003, for Quality management systems and guidelines for quality management in projects.

- PRINCE2, PRojects IN Controlled Environments.

- Association for Project Management Body of Knowledge[43]

- Team Software Process (TSP) from the Software Engineering Institute.

- Total Cost Management Framework, AACE International's Methodology for Integrated Portfolio, Program and Project Management.

- V-Model, an original systems development method.

- The Logical framework approach, which is popular in international development organizations.

- Australian Institute of Project Management (AIPM) has 4 levels of certification; CPPP, CPPM, CPPD & CPPE for Certified Practicing Project ... Partner, Manager, Director and Executive.

Project portfolio management

An increasing number of organizations are using what is referred to as project portfolio management (PPM) as a means of selecting the right projects and then using project management techniques[44] as the means for delivering the outcomes in the form of benefits to the performing private or not-for-profit organization.

Project management software

Project management software is software used to help plan, organize, and manage resource pools, develop resource estimates and implement plans. Depending on the sophistication of the software, functionality may include estimation and planning, scheduling, cost control and budget management, resource allocation, collaboration software, communication, decision-making, workflow, risk, quality, documentation and/or administration systems.[45][46]

Virtual project management

Virtual program management (VPM) is management of a project done by a virtual team, though it rarely may refer to a project implementing a virtual environment[47] It is noted that managing a virtual project is fundamentally different from managing traditional projects,[48] combining concerns of telecommuting and global collaboration (culture, timezones, language).[49]

See also

|

Related fields |

Related subjects |

Lists |

References

- ↑

- The Definitive Guide to Project Management. Nokes, Sebastian. 2nd Ed.n. London (Financial Times / Prentice Hall): 2007. ISBN 978-0-273-71097-4

- ↑ "What is Project Management? | Project Management Institute". Pmi.org. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ Paul C. Dinsmore et al (2005) The right projects done right! John Wiley and Sons, 2005. ISBN 0-7879-7113-8. p.35 and further.

- ↑ Cattani, G., Ferriani, S., Frederiksen, L. and Florian, T. (2011) Project-Based Organizing and Strategic Management, Advances in Strategic Management, Vol 28, Emerald, ISBN 1780521936.

- ↑ Joseph Phillips (2003). PMP Project Management Professional Study Guide. McGraw-Hill Professional, 2003. ISBN 0-07-223062-2 p.354.

- 1 2 3 4 PMI (2010). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge p.27-35

- ↑ Dennis Lock (2007) Project Management (9th ed.) Gower Publishing, Ltd., 2007. ISBN 0-566-08772-3

- ↑ Young-Hoon Kwak (2005). "A brief History of Project Management". In: The story of managing projects. Elias G. Carayannis et al. (9 eds), Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. ISBN 1-56720-506-2

- ↑ David I. Cleland, Roland Gareis (2006). Global Project Management Handbook. "Chapter 1: "The evolution of project management". McGraw-Hill Professional, 2006. ISBN 0-07-146045-4

- ↑ Martin Stevens (2002). Project Management Pathways. Association for Project Management. APM Publishing Limited, 2002 ISBN 1-903494-01-X p.xxii

- ↑ Edward R. Marsh (1975). "The Harmonogram of Karol Adamiecki". In: The Academy of Management Journal. Vol. 18, No. 2 (Jun., 1975), p. 358. (online)

- ↑ Morgen Witzel (2003). Fifty key figures in management. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0-415-36977-0. p. 96-101.

- ↑ David I. Cleland, Roland Gareis (2006). Global Project Management Handbook. McGraw-Hill Professional, 2006. ISBN 0-07-146045-4. p.1-4 states: "It was in the 1950s when project management was formally recognized as a distinct contribution arising from the management discipline."

- ↑ Malcolm, D. G., Roseboom, J. H., Clark, C. E., & Fazar, W. (1959). "Application of a technique for research and development program evaluation." Operations research, 7(5), 646-669.

- ↑ F. L. Harrison, Dennis Lock (2004). Advanced project management: a structured approach. Gower Publishing, Ltd., 2004. ISBN 0-566-07822-8. p.34.

- ↑ Mesly, Olivier. (2017). Project feasibility – Tools for uncovering points of vulnerability. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis, CRC Press. 546 pages. ISBN 9 781498 757911.

- ↑ Wysocki, Robert K (2013). Effective Project Management: Traditional, Adaptive, Extreme (Seventh Edition). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118729168.

- ↑ Winston W. Royce (1970). "Managing the Development of Large Software Systems" in: Technical Papers of Western Electronic Show and Convention (WesCon) August 25–28, 1970, Los Angeles, USA.

- 1 2 Stellman, Andrew; Greene, Jennifer (2005). Applied Software Project Management. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-00948-9.

- ↑ Hass, Kathleen B. (Kitty) (March 2, 2010). "Managing Complex Projects that are Too Large, Too Long and Too Costly". PM Times. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- ↑ Conforto, E. C.; Salum, F.; Amaral, D. C.; da Silva, S. L.; Magnanini de Almeida, L. F (June 2014). "Can agile project management be adopted by industries other than software development?". Project Management Journal. 45 (3): 21–34. doi:10.1002/pmj.21410.

- ↑ "Waterfall Project Management Explained". Daily Telegraph. February 3, 2016. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- ↑ Snowden, David J.; Boone, Mary E. (November 2007). "A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- ↑ "Stanford Research Study Finds Innovation Engineering is a true “Breakout Innovation” System". IE News. June 20, 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- ↑ Office for Government Commerce (1996) Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, p14

- ↑ OGC – PRINCE2 – Background

- ↑ McCaffer, Ronald; Harris, Frank (2013). Modern construction management. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 5. ISBN 1118510186. OCLC 834624541.

- ↑ Serra, C. E. M.; Kunc, M. (2014). "Benefits Realisation Management and its influence on project success and on the execution of business strategies". International Journal of Project Management. 33 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.03.011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Project Management Guide" (PDF). VA Office of Information and Technology. 2003. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Peter Nathan, Gerald Everett Jones (2003). PMP certification for dummies. p.63.

- ↑ Harold Kerzner (2003). Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, Scheduling, and Controlling (8th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-22577-0.

- 1 2 James P. Lewis (2000). The project manager's desk reference: : a comprehensive guide to project planning, scheduling, evaluation, and systems. p.185

- ↑ Jörg Becker, Martin Kugeler, Michael Rosemann (2003). Process management: a guide for the design of business processes. ISBN 978-3-540-43499-3. p.27.

- ↑ Bernhard Schlagheck (2000). Objektorientierte Referenzmodelle für das Prozess- und Projektcontrolling. Grundlagen – Konstruktionen – Anwendungsmöglichkeiten. ISBN 978-3-8244-7162-1. p.131.

- ↑ Josef E. Riedl (1990). Projekt – Controlling in Forschung und Entwicklung. ISBN 978-3-540-51963-8. p.99.

- ↑ Steinle, Bruch, Lawa (1995). Projektmanagement. FAZ Verlagsbereich Wirtschaftsbücher. p.136–143

- ↑ Cynthia Snyder, Frank Parth (2006). Introduction to IT Project Management. p.393-397

- ↑ "Certified Construction Manager". CMAA. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ "Certificate in Biotechnology Project Management". University of Washington. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ↑ "DoDD 5000.01" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- 1 2 NASA NPR 9501.2D. May 23, 2001.

- ↑ ISO/IEC/IEEE 16326-2009 – Systems and Software Engineering--Life Cycle Processes--Project Management. December 2009. DOI: 10.1109/IEEESTD.2009.5372630. ISBN 978-0-7381-6116-7

- ↑ Body of Knowledge 5th edition, Association for Project Management, 2006, ISBN 1-903494-13-3

- ↑ Albert Hamilton (2004). Handbook of Project Management Procedures. TTL Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7277-3258-7

- ↑ PMBOK 4h Ed. p. 443. ISBN 978-1933890517.

- ↑ Tom Kendrick. The Project Management Tool Kit: 100 Tips and Techniques for Getting the Job Done Right, Third Edition. AMACOM Books, 2013 ISBN 9780814433454

- ↑ Curlee, Wanda (2011). The Virtual Project Management Office: Best Practices, Proven Methods.

- ↑ Khazanchi, Deepak (2005). Patterns of Effective Project Management in Virtual Projects: An Exploratory Study. Project Management Institute. ISBN 9781930699830.

- ↑ Velagapudi, Mridula (April 13, 2012). "Why You Cannot Avoid Virtual Project Management 2012 Onwards".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Project management. |

| Library resources about Project management |

- Guidelines for Managing Projects from the UK Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR)