Prior Park

| Prior Park | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Location | Bath, Somerset, England |

| Coordinates | 51°21′54″N 2°20′40″W / 51.36500°N 2.34444°WCoordinates: 51°21′54″N 2°20′40″W / 51.36500°N 2.34444°W |

| Built | 1742 |

| Built for | Ralph Allen |

| Architect | John Wood, the Elder |

| Architectural style(s) | Palladian |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name: Prior Park (Now Prior Park College) | |

| Designated | 12 June 1950[1] |

| Reference no. | 443306 |

Location of Prior Park in Somerset | |

Prior Park is a Palladian house, designed by John Wood, the Elder, and built in the 1730s and 1740s for Ralph Allen on a hill overlooking Bath, Somerset, England. It has been designated as a Grade I listed building.

The house was built to demonstrate the properties of Bath stone as a building material. The design followed work by Andrea Palladio and was influenced by drawings originally made by Colen Campbell for Wanstead House in Essex. The main block had 15 bays and each of the wings 17 bays each. The surrounding parkland had been laid out in 1100 but following the purchase of the land by Allen 11.3 hectares (28 acres) were established as a landscape garden. Features in the garden include a bridge covered by Palladian arches, which is also Grade I listed.

Following Allen's death the estate passed down through his family. In 1828, Bishop Baines bought it for use as a Roman Catholic College. The house was then extended and a chapel and gymnasium built by Henry Goodridge. The house is now used by Prior Park College and the surrounding parkland owned by the National Trust.

History

Construction

Ralph Allen, an entrepreneur and philanthropist, was notable for his reforms to the British postal system. He moved in 1710 to Bath, where he became a post office clerk, and at the age of 19, in 1712, became the Postmaster.[2] In 1742 he was elected Mayor of Bath,[3] and was the Member of Parliament for Bath between 1757 and 1764.[3] The building in Lilliput Alley, now North Parade Passage in Bath, which he used as a post office, became his Town House.[4]

Allen acquired the stone quarries at Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines.[3] He used the unique honey-coloured Bath stone, used to build the Georgian city, and as a result made a second fortune. Allen built a railway line from his mine on Combe Down which carried the stone down the hill, now known as Ralph Allen Drive, which runs beside Prior Park, to a wharf he constructed at Bath Locks on the Kennet and Avon Canal to transport stone to London.[5] Following a failed bid to supply stone to buildings in London, Allen wanted a building which would show off the properties of Bath stone as a building material.[6][7]

Hitherto, the quarry masons had always hewn stone roughly providing blocks of varying size. Wood required stone blocks to be cut with crisp clean edges for his distinctive classical façades.[8] The Stone was extracted by the "room and pillar" method, by which chambers were mined, leaving pillars of stone to support the roof.[9] Bath stone is an Oolitic Limestone comprising granular fragments of calcium carbonate laid down during the Jurassic (195 to 135 million years ago). An important feature of Bath stone is that it is a freestone, that is one that can be sawn or 'squared up' in any direction, unlike other rocks such as slate, which forms distinct layers. It was extensively used in the Roman and Medieval periods on domestic, ecclesiastical and civil engineering projects such as bridges.[10]

John Wood, the Elder was commissioned by Ralph Allen to build on the hill overlooking Bath: "To see all Bath, and for all Bath to see".[3] Wood was born in Bath and is known for designing many of the streets and buildings of the city, such as The Circus (1754–68),[11] St John's Hospital,[12] (1727–28), Queen Square (1728–36), the North (1740) and South Parades (1743–48), The Royal Mineral Water Hospital (1738–42) and other notable houses, many of which are Grade I listed buildings. Queen Square was his first speculative development. Wood lived in a house on the square,[13] which was described by Nikolaus Pevsner as "one of the finest Palladian compositions in England before 1730".[14]

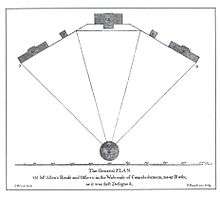

The plan for Prior Park was to construct five buildings along three sides of a dodecagon matching the sweep of the head of the valley, with the main building being flanked by elongated wings based on designs by Andrea Palladio.[7] The plans were influenced by drawings in Vitruvius Britannicus originally made by Colen Campbell for Wanstead House in Essex, which was yet to be built.[7][5] The main block had 15 bays and each of the wings 17 bays each. Between each wing and the main block was a Porte-cochère for coaches to stop under.[5] In addition to the stone from the local quarries, material, including the grand staircase and plasterwork, from the demolished Hunstrete House were used in the construction.[15][16]

Construction work began in 1734 to Wood's plan but disagreements between Wood and Allen led to his dismissal and Wood's Clerk of Works, Richard Jones, replaced him and made some changes to the plans particularly for the east wing.[5][17] Jones also added the Palladian Bridge.[18] The building was finished in 1743 and was occupied by Allen as his primary residence until his death in 1764.[19]

Later use

After Allen's death in 1764, William Warburton, Allen's relative, lived in the house for some time and it was passed down to other family members and then purchased, in 1809, by John Thomas, a Bristol Quaker.[20][6] After William Beckford sold Fonthill Abbey, in 1822, he was looking about for a suitable new seat, Prior Park was his first choice: ""They wanted too much for it," he recalled later; "I should have liked it very much; it possesses such great capability of being made a very beautiful spot."[21] Prior Park was offered for sale after Thomas's death in 1827 but the asking price of £25,000 was not obtained and the offer of sale withdrawn.[20]

Augustine Baines, a Benedictine, Titular Bishop of Siga and Vicar Apostolic of the Western District of England, was appointed to Bath in 1817. He purchased the mansion in 1828 for £22,000 and set to work to establish two colleges in either wing of the house, which he dedicated to St. Peter and St. Paul respectively, the former being intended as a lay college, the latter as a seminary. The new college never became prosperous, however. Renovations were made according to designs by Henry Goodridge in 1834 including the addition of the staircase in front of the main building.[5][22] A gymnasium was also built in the 1830s including a courtyard for Fives,[23] and three barrel vaulted rooms on the first floor and a terrace roof.[24]

The seminary was closed in 1856 after a fire which, in 1836, had resulted in extensive damage and renovation and brought about financial insolvency. It was bought in 1867 by Bishop Clifford who founded a Roman Catholic Grammar School in the mansion.[6] Prior Park operated as a grammar school until 1904. During World War I the site was occupied by the army. Following the war several tenants occupied the site. In 1921, the Christian Brothers acquired the building. They opened a boarding school for boys in 1924.[25]

The main building (the Mansion) has been badly burnt twice. The 1836 fire left visible damage to some stonework.[26] The 1991 fire gutted the interior, except for parts of the basement.[27] Unusually, the blaze started on the top floor, and spread downwards. Rebuilding took approximately three years.[28]

The site continues on in use as a School, Prior Park College, one of four schools owned by The Prior Foundation (the other three are Prior Park Preparatory School, in Cricklade, Wiltshire, The Paragon School in Bath, located just down the hill from the main College in the vale of Lyncombe, and Prior Park School, in Gibraltar).[29]

Architecture

The house described by Pevsner [30] as "the most ambitious and most complete re-creation of Palladio's villas on English soil" was designed by John Wood the Elder, however, Wood and his patron, Allen, quarrelled and completion of the project was overseen by Richard Jones, the clerk-of-works.[7]

The plan consists of a corps de logis flanked by two pavilions connected to the corps de logis by segmented single storey arcades. The northern façade (or garden façade) of the corps de logis is of 15 bays,[1] the central 5 bays carry a prostyle portico of six Corinthian columns. The southern façade is more sombre in its embellishment, but has at its centre, six ionic columns surmounted by a pediment. The terminating pavilions have been much altered from their original design by Wood; he originally envisaged two pavilions at each end of the range; an unusual composition which was ignored by Jones who terminated the range with a single pavilion as is the more conventional Palladian concept.[30] The East Wing was altered around 1830 when it was converted into a school, having included a brewhouse previously when a pedimented three-bay second floor was added by John Pensiston.[31] Around 1834 Goodridge altered the West Wing to include a theatre, which was damaged by bombs during the Bath Blitz of 1942.[7] The central flight of steps and urns, in Baroque style, which front the north portico were added by Goodridge in 1836.[1]

In the 1830s Goodridge put forward plans for a large cathedral to be built in the grounds. However this was never proceeded with and instead was replaced by a plan for a small chapel to be incorporated in the west wing of the mansion.[32] In 1844 Joseph John Scoles created the Church of St Paul which, along with the remainder of the west wing, is Grade I listed.[33][1]

The total length of the principal elevation is between 1,200 feet (370 m) and 1,300 feet (400 m) in length. Of that, the corps de logis occupies 150 feet (46 m).[34] The two storey building with attics and a basement is topped with a Westmorland slate roof.[1]

Gardens

The first park on the site was set out by John of Tours the Bishop of Bath and Wells around 1100, as part of a deer park, and subsequently sold to Humphrey Colles and then Matthew Colhurst.[6] It is set in a small valley with steep sides, from which there are views of the city of Bath. Prior Park's 11.3 hectares (28 acres) landscape garden was laid out by the poet Alexander Pope between the construction of the house and 1764. During 1737, at least 55,200 trees, mostly elm and Scots pine, were planted, along the sides and top of the valley. No trees were planted on the valley floor. Water was channeled into fish ponds at the bottom of the valley.[6]

Later work, during the 1750s and 1760s, was undertaken by the landscape gardener Capability Brown.[35][36] This included extending the gardens to the north and removing the central cascade making the combe into a single sweep.[6] The garden, as it was originally laid out, influenced other designers and contributed to defining the style of garden thought of as the English garden in continental Europe.[37]

The features in the gardens include a Palladian bridge (one of only 4 left in the world), Gothic temple, gravel cabinet, Mrs Allen's Grotto,[38] ice house,[39] lodge[40] and three pools with curtain walls[41] plus a serpentine lake. The Palladian bridge, which is a copy of the one at Wilton House,[5] was built by Richard Jones,[42] and has been designated as a Grade I listed building[43] and Scheduled Ancient Monument.[44][43] It was repaired in 1936.[45]

The rusticated stone piers on either side of the main entrance gates are surmounted by entablatures and large ornamental vases,[46] while those at the drive entrance have ornamental carved finials.[47] The porter's lodge was built along with the main house to designs by John Wood the Elder.[48]

In 1993, the National Trust obtained the park and pleasure grounds. In November 2006, the large-scale restoration project began on the cascade, serpentine lake and Gothic temple in the Wilderness area, this is now complete.[37] Extensive planting also took place in 2007. The Palladian Bridge is also featured on the cover of the album Morningrise by Swedish progressive metal band Opeth released in 1996.[49][50]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Historic England. "Prior Park College: The mansion with linked arcades) (1394453)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Staff 1964, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ralph Allen Biography". Bath Postal Museum. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ↑ "Ralph Allen's House, Terrace Walk, Bath". Images of England. Historic England. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Durman 2000, pp. 91–94.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Prior Park, Bath, England". Parks and gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services Ltd. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Forsyth 2003, p. 94.

- ↑ Greenwood 1977, pp. 70–74.

- ↑ "Combe Down Stone Mines Land Stabilisation Project". BANES. Archived from the original on 17 January 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- ↑ "Tales From The Riverbank". Minerva Conservation. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ↑ "The Circus". Images of England. Historic England. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ↑ "St John's Hospital (including Chapel Court House)". Images of England. Historic England. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ↑ "Queen Square". UK attractions. Archived from the original on 19 April 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- ↑ "Queen Square". Bath Net. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- ↑ "Hunstrete Grand Mansion". Wessex Archeology. Videotext Communications Ltd. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ↑ "Combe Down, "Alice is a sexy sl*t" Was Here: Modern vs. Historical Graffiti". Bath Daily Photo. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ↑ Varey 1990, pp. 112–117.

- ↑ Curl 2002, p. 44.

- ↑ "History of Prior Park College". Prior Park Alumni. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- 1 2 "John Thomas – the forgotten man of Prior Park". Combe Down. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ↑ Benjamin 1910, p. 322.

- ↑ Richardson 2001, p. 65.

- ↑ "The Gymnasium to north of North Road". Images of England. Historic England. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "Monument No. 204217". Pastscape National Monument Record. Historic England. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ↑ "Prior Park". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ↑ Colvin & Mellon 2008, p. 1143.

- ↑ Gillie, Oliver (6 April 1994). "Craftsmen restore country house to former glory: Sculptors use delicate skills to recreate rococo ceiling destroyed by fire". London: The Independent. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- ↑ Gillie, Oliver (5 April 1994). "Craftsmen restore country house to former glory: Sculptors use delicate skills to recreate rococo ceiling destroyed by fire.". Independent. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ↑ "Prior Park Schools". The Prior Foundation. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- 1 2 Pevsner 2002, p. 114.

- ↑ Forsyth 2003, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Goodridge 1865, p. 5.

- ↑ Historic England. "Church of St Paul, with West Wing (1394459)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ Kilvert 1857, p. 11.

- ↑ "Green Priorities for the National Trust at Prior Park". questia.com. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ↑ "Prior Park Landscape Garden". National Trust. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Prior Park Landscape Garden". Minerva Stone Conservation. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ↑ Historic England. "Grotto in grounds of Prior Park (1394467)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Ice-house in grounds of Prior Park (1394461)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Prior Park Lodge (1394608)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "Screen wall to pool below the West Pavilion and Church of St Paul". Images of England. Historic England. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Forsyth 2003, p. 99.

- 1 2 Historic England. "Palladian Bridge in grounds of Prior Park (1394463)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "List of Scheduled Ancient Monuments". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ↑ Borsay 2000, p. 161.

- ↑ Historic England. "Gate Posts at entrance to Prior Park (1394605)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Gate Posts to Drive at Prior Park (1394606)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ "Porters Lodge". Images of England. Historic England. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "Morningrise". Last FM. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ↑ "Morningrise Opeth". Metal Archives. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

Bibliography

- Benjamin, Lewis Saul (1910). The life and letters of William Beckford of Fonthill. Duffield.

- Borsay, Peter (2000). The image of Georgian Bath, 1700–2000: towns, heritage, and history. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820265-3.

- Clarke, Gillian (1987). Prior Park: A complete landscape. Millstream Books. ISBN 978-0-948975-06-6.

- Colvin, Howard; Mellon, Paul (2008). A biographical dictionary of British architects, 1600–1840 (4 ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12508-5.

- Curl, James Stevens (2002). Georgian architecture. David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-0227-9.

- Durman, Richard (2000). Classical Buildings of Wiltshire & Bath: A Palladian Quest. Bath: Millstream Books. ISBN 978-0-948975-60-8.

- Forsyth, Michael (2003). Pevsner Architectural Guides: Bath. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10177-5.

- Goodridge, Alfred S. (1865). Transactions. Royal Institute of British Architects.

- Greenwood, Charles (1977). Famous houses of the West Country. Bath: Kingsmead Press. ISBN 978-0-901571-87-8.

- Kilvert, Robert Francis (1857). Ralph Allen and Prior Park. Oxford University.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). North Somerset and Bristol: North and Bristol. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09640-8.

- Richardson, Albert E. (2001). Monumental Classic Architecture in Great Britain and Ireland. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-41534-5.

- Staff, Frank (1964). The Penny Post, 1680–1918. Lutterworth. ASIN B0000CM5GS.

- Varey, Simon (1990). Space and the eighteenth-century English novel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37483-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prior Park. |