Priapulida

| Priapulida Temporal range: Late Pennsylvanian–Recent[1] (Priapulid-like burrows from Cambrian) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Priapulus caudatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Clade: | Vinctiplicata |

| Phylum: | Priapulida Théel, 1906[2] |

| Classes | |

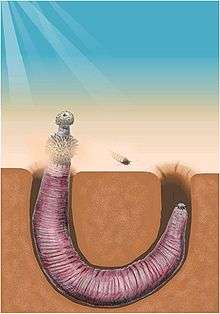

Priapulida (priapulid worms or penis worms, from Gr. πριάπος, priāpos 'Priapus' + Lat. -ul-, diminutive) is a phylum of marine worms. The name of the phylum relates to the Greek god of fertility, because their general shape and their extensible spiny introvert (eversible proboscis) may recall the shape of a penis. They live in the mud (which they eat) and in comparatively shallow waters up to 90 metres (300 ft) deep. Some species show a remarkable tolerance for hydrogen sulfide and anoxia.[3]

Together with Echiura and Sipuncula, they were once placed in the taxon Gephyrea, but consistent morphological and molecular evidence supports their belonging to Ecdysozoa, which also includes arthropods and nematodes. Fossil findings show that the mouth design of the stem-arthropod Pambdelurion is identical with that of priapulids, indicating that their mouth is an original trait inherited from the last common ancestor of both priapulids and arthropods, even if modern arthropods no longer possess it.[4] Among Ecdysozoa, their nearest relatives are Kinorhyncha and Loricifera, with which they constitute the Scalidophora clade named after the spines covering the introvert (scalids).[5] They feed on slow-moving invertebrates, such as polychaete worms.

Priapulid-like fossils are known at least as far back as the Middle Cambrian. They were likely major predators of the Cambrian period. However, crown-group priapulids cannot be recognized until the Carboniferous.[1] About 20 extant species of priapulid worms are known, half of them being of meiobenthic size.[6]

Anatomy

Priapulids are cylindrical worm-like animals, ranging from 0.2–0.3[7] to 39 centimetres[8] ( 0.08–0.12 to 15.35 in) long, with a median anterior mouth quite devoid of any armature or tentacles. The body is divided into a main trunk or abdomen and a somewhat swollen proboscis region ornamented with longitudinal ridges. The body is ringed and often has circles of spines, which are continued into the slightly protrusible pharynx. Some species may also have a tail or a pair of caudal appendages. The body has a chitinous cuticle that is moulted as the animal grows.[9]

There is a wide body-cavity, which has no connection with the renal or reproductive organs, so it is not a coelom; it is probably a blood-space or hemocoel. There are no vascular or respiratory systems, but the body cavity does contain phagocytic amoebocytes and cells containing the respiratory pigment haemerythrin.[9]

The alimentary canal is straight, consisting of an eversible pharynx, an intestine, and a short rectum. The pharynx is muscular and lined by teeth.[9] The anus is terminal, although in Priapulus one or two hollow ventral diverticula of the body-wall stretch out behind it.

The nervous system consists of a nerve ring around the pharynx and a prominent cord running the length of the body with ganglia and longitudinal and transversal neurites consistent with an orthogonal organisation.[10] The nervous system retains a basiepidermal configuration with a connection with the ectoderm, forming part of the body wall. There are no specialized sense organs, but there are sensory nerve endings in the body, especially on the proboscis.[9]

The priapulids are gonochoristic, having two separate sexes (i.e. male and female)[11] Their male and female organs are closely associated with the excretory protonephridia. They comprise a pair of branching tufts, each of which opens to the exterior on one side of the anus. The tips of these tufts enclose a flame-cell like those found in flatworms and other animals, and these probably function as excretory organs. As the animals mature, diverticula arise on the tubes of these organs, which develop either spermatozoa or ova. These sex cells pass out through the ducts.

Reproduction and development

Priapulid development has been reappraised recently because early studies reported abnormal development caused by high temperature of embryo culture. For the species Priapulus caudatus, the 80 µm egg undergoes a total and radial cleavage following a symmetrical and subequal pattern.[12] Development is remarkably slow, with the first cleavage taking place 15 hours after fertilization, gastrulation after several days and hatching of the first 'lorica' larvae after 15 to 20 days.[13] In current systematics, they are described as protostomes, even if they have a deuterostomic development.[14] It is assumed the reason is because the group is so ancient that the original deuterostome traits that are assumed to have been present in early animals, are still there.[15]

Fossil record

Stem-group priapulids are known from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale, where their soft-part anatomy is preserved, often in conjunction with their gut contents – allowing a reconstruction of their diets.[16] In addition, isolated microfossils (corresponding to the various teeth and spines that line the pharynx and introvert) are widespread in Cambrian deposits, allowing the distribution of priapulids – and even individual species – to be tracked widely through Cambrian oceans.[17] Trace fossils that are morphologically almost identical to modern priapulid burrows (Treptichnus pedum) officially mark the start of the Cambrian period, suggesting that priapulids, or at least close anatomical relatives, evolved around this time.[16] Crown-group priapulid body fossils are first known from the Carboniferous.[1]

Classification

Uncertain relationship

- "Class" Palaeoscolecida

Stem-group Priapulida

- Class †Archaeopriapulida

- Family †Ottoiidae

- Genus †Ancalagon

- Genus †Fieldia

- Genus †Lecythioscopa

- Genus †Ottoia

- Genus †Scolecofurca

- Genus †Selkirkia

- Family †Louisellidae

- Genus †Anningvermis

- Genus †Corynetis

- Genus †Louisella

- Family †Ottoiidae

Phylum Priapulida

- Class Priapulimorpha

- Order Priapulimorphida

- Family Priapulidae

- Genus Acanthopriapulus

- Genus Priapulopsis

- Genus Priapulus

- Family Tubiluchidae

- Genus Meiopriapulus

- Genus Tubiluchus

- Family Priapulidae

- Order Priapulimorphida

- Class Halicryptomorpha

- Order Halicryptomorphida

- Family Halicryptidae

- Genus Halicryptus

- Family Halicryptidae

- Order Halicryptomorphida

- Class Seticoronaria

- Order Seticoronarida

- Family Maccabeidae

- Genus Maccabeus

- Family Maccabeidae

- Order Seticoronarida

References

- 1 2 3 Budd, G. E.; Jensen, S. (May 2000). "A critical reappraisal of the fossil record of the bilaterian phyla". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 75 (2): 253–95. PMID 10881389. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1999.tb00046.x.

- ↑ Théel, Hjalmar. "Northern and Arctic Invertebrates in the Collection of the Swedish State Museum (Riksmuseum). II. Priapulids, Echiurids etc.". Kungl. Svenska vetenskapsakademiens handlingar. 40 (4): 8–13.

- ↑ Oeschger, R.; Janssen, H. H. (September 1991). "Histological studies on Halicryptus spinulosus (Priapulida) with regard to environmental hydrogen sulfide resistance". Hydrobiologia. 222: 1. doi:10.1007/BF00017494.

- ↑ Ancestor of arthropods had the mouth of a penis worm

- ↑ Dunn, C. W.; Hejnol, A.; Matus, D. Q.; Pang, K.; Browne, W. E.; Smith, S. A.; Seaver, E.; Rouse, G. W.; Obst, M. (10 April 2008). "Broad Phylogenomic Sampling Improves Resolution of the Animal Tree of Life". Nature. 452 (7188): 745–749. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..745D. PMID 18322464. doi:10.1038/nature06614.

- ↑ Meiobenthology: The Microscopic Motile Fauna of Aquatic Sediments

- ↑ Ax, Peter (2003-04-08). Multicellular Animals: Order in Nature – System Made by Man. ISBN 978-3-540-00146-1.

- ↑ "Halicryptus higginsi n.sp. (Priapulida): A Giant New Species from Barrow, Alaska". 118: 404–413. JSTOR 3227009.

- 1 2 3 4 Barnes, R. D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 873–877. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ↑ Rothe, B. H.; Schmidt-Rhaesa, A. (Winter 2010). "Structure of the nervous system in Tubiluchus troglodytes (Priapulida)". Invertebrate Biology. 129: 39. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7410.2010.00185.x.

- ↑ Pechenik, J. A. (2009). Biology of the Invertebrates (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-07-302826-2.

- ↑ Wennberg, S. A.; Janssen, R.; Budd, G. E. (May–June 2008). "Early embryonic development of the priapulid worm Priapulus caudatus". Evolution & Development. 10 (3): 326–338. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00241.x.

- ↑ Janssen, R.; Wennberg, S. A.; Budd, G. E. (26 May 2009). "The hatching larva of the priapulid worm Halicryptus spinulosus". Frontiers in Zoology. 6: 8. PMC 2693540

. PMID 19470151. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-6-8.

. PMID 19470151. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-6-8. - ↑ Martín-Durán, J. M.; Janssen, R.; Wennberg, S.; Budd, G. E.; Hejnol, A. (2012). "Deuterostomic Development in the Protostome Priapulus caudatus". Current Biology. 22 (22): 2161–2166. PMID 23103190. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.037.

- ↑ Penis worms show the evolution of the digestive system

- 1 2 Vannier, J.; Calandra, I.; Gaillard, C.; Zylinska, A. (2010). "Priapulid worms: Pioneer horizontal burrowers at the Precambrian-Cambrian boundary". Geology. 38 (8): 711–714. doi:10.1130/G30829.1.

- ↑ Smith, M. R.; Harvey, T. H. P.; Butterfield, N. J. (July 2015). "The macro- and microfossil record of the Cambrian priapulid Ottoia". Palaeontology. 58 (4): 705–721. doi:10.1111/pala.12168.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Priapulida |

- "Evolution of the penis worm". Press Releases. University of Bristol. 2006-08-09.

- Strange Worm Found