Presidency of Woodrow Wilson

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of the United States First Term

Second Term World War I

|

||

The presidency of Woodrow Wilson began on March 4, 1913 at noon when Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1921. Wilson, a Democrat, took office as the 28th United States president after winning the 1912 presidential election, gaining a large majority in the Electoral College and a 42 percent plurality of the popular vote in a four–candidate field. Four years later, in 1916, Wilson defeated Republican Charles Evans Hughes by nearly 600,000 votes in the popular vote and secured a narrow majority in the Electoral College by winning several swing states with razor-thin margins. He was the first Southerner elected as president since Zachary Taylor in 1848,[1] and the first Democratic president to win re-election since Andrew Jackson in 1832.

Wilson was a leading force in the Progressive Movement, and during his first term he oversaw the passage of progressive legislative policies unparalleled until the New Deal. Included among these were the Federal Reserve Act, Federal Trade Commission Act, the Clayton Antitrust Act, and the Federal Farm Loan Act. Having taken office one month after ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment, Wilson called a special session of Congress, whose work culminated in the Revenue Act of 1913, reintroducing an income tax and lowering tariffs. Through passage of the Adamson Act, imposing an 8-hour workday for railroads, he averted a railroad strike and an ensuing economic crisis. Upon the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Wilson maintained a policy of neutrality, while pursuing a more aggressive policy in dealing with Mexico's civil war.

Wilson's second term was dominated by the American entry into World War I and the aftermath of that war. In April 1917, when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, Wilson asked Congress to declare war in order to make "the world safe for democracy." Through the Selective Service Act, conscription sent 10,000 freshly trained soldiers to France per day by the summer of 1918. On the home front, Wilson raised income taxes, set up the War Industries Board, promoted labor union cooperation, regulated agriculture and food production through the Lever Act, and nationalized the nation's railroad system. In his 1915 State of the Union, Wilson asked Congress for what became the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, suppressing anti-draft activists. The crackdown was later intensified by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer to include expulsion of non-citizen radicals during the First Red Scare of 1919–1920. Wilson infused morality into his internationalism, an ideology now referred to as "Wilsonian"—an activist foreign policy calling on the nation to promote global democracy.[2][3][4] Early in 1918, he issued his principles for peace, the Fourteen Points, and in 1919, following the signing of an armistice with Germany, he traveled to Paris, promoting the formation of a League of Nations, concluding the Treaty of Versailles. Following his return from Europe, Wilson embarked on a nationwide tour in 1919 to campaign for the treaty, but suffered a severe stroke and saw the treaty defeated by the Senate.

Disability having diminished his power and influence in the waning days of his presidency, Wilson held out hope for a third term, but his party nominated Governor James M. Cox instead. In the 1920 presidential election, Cox lost in a landslide to Republican Warren G. Harding, who succeeded Wilson in office. Historians and political scientists rank Wilson as an above-average president, and his presidency was an important forerunner of modern American liberalism. However, Wilson has also been criticized for his racist views and actions.

Presidential election of 1912

Wilson became a prominent 1912 presidential contender immediately upon his election as Governor of New Jersey in 1910, and his clashes with state party bosses enhanced his reputation with the rising Progressive movement.[5] Wilson made a special effort to win the approval of three-time Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan, whose followers had largely dominated the Democratic Party since the 1896 presidential election.[6] Speaker of the House Champ Clark of Missouri was viewed by many as the front-runner for the nomination, while House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood of Alabama also loomed as a challenger. Clark found support among the Bryan wing of the party, while Underwood appealed to the conservative Bourbon Democrats, especially in the South.[7] On the first ballot of the 1912 Democratic National Convention, Clark won a plurality of delegates, and on the tenth ballot, he won a majority of the delegates after the New York Tammany Hall machine threw its support behind Clark. However, the Democratic Party required a nominee to win two-thirds of the delegates to win the nomination, and balloting continued.[8] The Wilson campaign picked up additional delegates by promising the vice presidency to Governor Thomas R. Marshall of Indiana, while several Southern delegations shifted their support from Underwood to Wilson, a native Southerner. Wilson finally won two-thirds of the vote on the convention's 46th ballot, and Marshall became Wilson's running mate.[9]

Wilson faced two major opponents in the 1912 general election: one-term Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, and former Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, who ran a third party campaign as the "Bull Moose" Party nominee. A fourth candidate, Eugene V. Debs of the Socialist Party, would also win a significant share of the popular vote. Roosevelt had broken with his former party at the 1912 Republican National Convention after Taft narrowly won re-nomination, and the split in the Republican Party made Democrats hopeful that they could win the presidency for the first time since the 1892 presidential election.[10] Roosevelt emerged as Wilson's main challenger, and Wilson and Roosevelt largely campaigned against each other despite sharing similarly progressive platforms that called for a strong, interventionist central government.[11] Wilson won 435 of the 531 electoral votes and 41.8% of the popular vote, while Roosevelt won most of the remaining electoral votes and 27.4% of the popular vote, representing one of the strongest third party performances in U.S. history. Taft won 23.2% of the popular vote but just 8 electoral votes, while Debs won 6% of the popular vote. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats retained control of the House and won a majority in the Senate. Wilson became the first Southerner to win the presidency since the Civil War.[12]

Personnel and appointments

Cabinet and administration

After the election, Wilson quickly chose William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State, and Bryan offered advice on the remaining members of Wilson's cabinet.[13] William Gibbs McAdoo, a prominent Wilson supporter who would marry Wilson's daughter in 1914, became Secretary of the Treasury, while James Clark McReynolds, who had successfully prosecuted prominent anti-trust cases, was chosen as Attorney General. On the advice of Underwood, Wilson appointed Texas Congressman Albert S. Burleson as Postmaster General.[14] Bryan resigned in 1915 due to his opposition to Wilson hard line towards Germany in the aftermath of the Sinking of the RMS Lusitania.[15] Bryan was replaced by Robert Lansing, and Wilson took more direct control of his administration's foreign policy after Bryan's departure.[16] Bryan continued to oppose the war after leaving the cabinet, but Wilson eclipsed Bryan's standing within the Democratic Party and was able to win legislative support for his preparedness policies.[17] Newton D. Baker, a progressive Democrat, became Secretary of War in 1916, and Baker led the War Department during World War I.[18] Wilson's cabinet experienced turnover after the conclusion of World War I, with Carter Glass replacing McAdoo as Secretary of the Treasury and A. Mitchell Palmer becoming Attorney General.[19]

Wilson's chief of staff ("Secretary") was Joseph Patrick Tumulty from 1913 to 1921. Tumulty's position provided a political buffer and intermediary with the press, and his irrepressible Irish spirits offset the president's often dour Scotch disposition.[20] Wilson's first wife, Ellen Axson Wilson died on August 6, 1914.[21] Wilson married Edith Bolling Galt in 1915,[22] and she assumed full control of Wilson's schedule, diminishing Tumulty's power. The most important foreign policy advisor and confidant was "Colonel" Edward M. House until Wilson broke with him in early 1919, for his missteps at the peace conference in Wilson's absence.[23] Wilson's vice president, former Governor Thomas R. Marshall of Indiana, played little role in the administration.[24]

| The Wilson Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Woodrow Wilson | 1913–1921 |

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of State | William J. Bryan | 1913–1915 |

| Robert Lansing | 1915–1920 | |

| Bainbridge Colby | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | William G. McAdoo | 1913–1918 |

| Carter Glass | 1918–1920 | |

| David F. Houston | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of War | Lindley M. Garrison | 1913–1916 |

| Newton D. Baker | 1916–1921 | |

| Attorney General | James C. McReynolds | 1913–1914 |

| Thomas W. Gregory | 1914–1919 | |

| A. Mitchell Palmer | 1919–1921 | |

| Postmaster General | Albert S. Burleson | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Josephus Daniels | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Franklin K. Lane | 1913–1920 |

| John B. Payne | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | David F. Houston | 1913–1920 |

| Edwin T. Meredith | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | William C. Redfield | 1913–1919 |

| Joshua W. Alexander | 1919–1921 | |

| Secretary of Labor | William B. Wilson | 1913–1921 |

Judicial appointments

Wilson appointed three individuals to the United States Supreme Court while president. He appointed James Clark McReynolds in 1914; McReynolds would serve until 1941, becoming a member of the conservative bloc of the court.[26] After the death of Joseph Rucker Lamar in 1916, Wilson nominated Louis Brandeis to the court. Brandeis proved to be a controversial nominee, with many in the Senate opposing him to due to his progressive ideology and his religion (Brandeis was the first Jewish nominee to the Supreme Court). However, Wilson was able to convince Senate Democrats to vote for Brandeis, and he won confirmation after months of Senate consideration, serving until 1939.[27] A second vacancy arose in 1916 after the resignation of Charles Evans Hughes, and Wilson appointed John Hessin Clarke, a progressive lawyer from the electorally-important state of Ohio, to replace Hughes. Clarke would resign from the court in 1922.[28]

In addition to his three Supreme Court appointments, Wilson also appointed 20 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals and 52 judges to the United States district courts.

Press corps

Wilson pioneered twice-weekly press conferences in the White House. Even though they were modestly effective, the president prohibited his being quoted and was particularly indeterminate in his statements.[29] The first such press conference was held on March 15, 1913, when reporters were allowed to ask him questions.[30]

Domestic policy

With the support of the Democratic Congress, Wilson introduced a comprehensive program of domestic legislation at the outset of his administration, something no president had ever done before.[31] The newly-inaugurated Wilson had four major priorities: the conservation of natural resources, banking reform, a lower tariff, and equal access to raw materials, which would be accomplished in part through the regulation of trusts.[32] Though foreign affairs would increasingly dominate his presidency starting in 1915, Wilson's first two years in office largely focused on domestic policy, and Wilson found success in implementing much of his ambitious "New Freedom" agenda.[33]

Tariff legislation

Wilson chose to pursue tariff legislation first, eventually leading to the passage of the Revenue Act of 1913, also known as the Underwood Tariff. Though tariff reduction had long been a priority of both Democrats and some Republicans, such as Taft, the Senate had consistently blocked the implementation of new rates. By the end of May 1913, House Majority Leader Oscar Underwood had already passed a bill in the House that cut the average tariff rate by ten percent and instituted a tax on personal income above $4,000, but the Senate remained an obstacle to the bill. Wilson met extensively with Democratic Senators in hopes of marshaling support for the Underwood Tariff, and he also appealed directly to the people through the press to call for lower tariffs. After weeks of hearings and debate, Wilson and Secretary of State Bryan were able to unite Democrats behind the bill. The Senate voted 44 to 37 in favor of the bill, with only one Democrat voting against it and only one Republican, progressive leader Robert M. LaFollette, voting for it. Wilson signed the tariff bill into law on October 3, 1913.[34] The effects of the new tariff were soon overwhelmed by the changes in trade caused by World War I.[35]

Federal Reserve System

Wilson did not wait for completion of the tariff legislation to proceed with his next item of reform—banking, which he initiated in June 1913. Though countries such as Britain and Germany had government-owned central banks, the United States had not had a central bank since the Bank War of the 1830s, [36] After consulting with Brandeis, Wilson declared that the banking system must be "public not private, must be vested in the government itself so that the banks must be the instruments, not the masters, of business."[37] He tried to look for a middle ground between conservative Republicans, led by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, and the powerful left wing of the Democratic party, led by Bryan, who strenuously denounced private banks and Wall Street. The latter group wanted a government-owned central bank that could print paper money as Congress required. The compromise, based on the Aldrich Plan but sponsored by Democratic Congressmen Carter Glass and Robert L. Owen, allowed the private banks to control the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, but appeased the agrarians by placing controlling interest in the System in a central board appointed by the president with Senate approval. Moreover, Wilson convinced Bryan's supporters that because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government, the plan met their demands for an elastic currency. Having 12 regional banks, with designated geographic districts, was intended to weaken the influence of the powerful ones in New York; this was a "key demand" of Bryan's allies in the South and West, and also a "key factor" in winning Glass' support.[38] The Federal Reserve Act was passed in December 1913.[39]

Wilson appointed Paul Warburg and other prominent bankers to direct the new system. While power was supposed to be decentralized, the New York branch dominated the Fed. as the "first among equals."[40] The new system began operations in 1915 and played a major role in financing the Allied and American war effort in World War I.[41]

Antitrust

Having passed major legislation lowering the tariff and reforming the banking structure, Wilson next sought anti-trust legislation that would provide for more regulation than the Sherman Antitrust Act.[42] Wilson broke with his predecessors' practice of litigating the antitrust issue in the courts, known as "trust-busting"; the new Federal Trade Commission provided a new regulatory approach, to encourage competition and reduce perceived unfair trade practices. In addition, he pushed the Clayton Antitrust Act through Congress making certain business practices illegal, such as price discrimination, agreements prohibiting retailers from handling other companies' products, and directorates and agreements to control other companies. The power of this legislation was greater than that of previous anti-trust laws since it dictated the accountability of individual corporate officers and clarified guidelines. This law was nicknamed the "Magna Carta of Labor" by Samuel Gompers, as it ended union liability antitrust laws. Under the threat of a national railroad strike in 1916, Wilson approved legislation that increased wages and cut working hours of railroad employees; in fact, there was no strike at all.[43]

Labor issues

In adispute between Colorado miners and their fuel and iron company in 1914, a confrontation resulted in the Ludlow Massacre, which caused the deaths of eight strikers, eleven children, and two mothers. Part owner John D. Rockefeller, Jr. refused Wilson's offer of mediation, conditioned upon collective bargaining, so Wilson sent in U.S. troops. While Wilson succeeded in bringing order to the situation and demonstrated support for the labor union, the miners' unconditional surrender to the implacable owners was a defeat for Wilson.[44]

Child labor was curtailed by the Keating–Owen Act of 1916, regulating interstate commerce involving goods produced by employees under the ages of either 14 or 16, depending on what kind of work was being done. However, two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the law down in court case Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), declaring that the law violated the Commerce Clause by regulating intrastate commerce. Later, a 1924 Child Labor Amendment to the Constitution, authorizing Congress to regulate "labor of persons under eighteen years of age", languished when sent to the states for ratification.[45] The passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 accomplished many of the reforms Congress sought, and the Supreme Court upheld the law.[46]

In the summer of 1916, the nation's economy was endangered by a railroad strike. The president called the parties to a White House summit in August—after two days and no results, Wilson proceeded to settle the issue, using the maximum eight-hour work day as its linchpin. Congress passed the Adamson Act, incorporating the president's proposal, and the strike was cancelled. Wilson was praised for averting a national economic disaster, though the law was received with howls from conservatives denouncing a sellout to the unions and a surrender by Congress to an imperious president.[47]

Other measures

With the President reaching out to new constituencies, a series of programs were targeted at farmers. The Smith–Lever Act of 1914 created the modern system of agricultural extension agents sponsored by the state agricultural colleges. The agents taught new techniques to farmers. The Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916 provided for issuance of low-cost long-term mortgages to farmers.[48]

Wilson supported the gradual autonomy and ultimate independence of the Philippines, which the United States had taken control of in the Spanish–American War. Wilson increased Filipino self-governance by granting natives greater control over the Philippine Legislature. The House also passed a measure to grant the Philippines full independence, but this act was strongly opposed by Republicans and was blocked in the Senate. The Jones Act of 1916 committed the United States to the eventual independence of the Philippines, but it did not establish a deadline for that independence.[49] The Jones Act of 1917 upgraded the status of Puerto Rico, which had also been acquired from Spain in 1898. The act, which superseded the Foraker Act, created the Senate of Puerto Rico, established a bill of rights, and authorized the election of a Resident Commissioner (previously appointed by the President) to a four-year term. The Resident Commissioner serves as a non-voting member of the U.S. House of Representatives. The act also granted Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship and exempted Puerto Rican bonds from federal, state, and local taxes. Puerto Rico, which remains a U.S. territory, would eventually adopt its own constitution in the 1950s.[50]

Wilson opposed the restrictive immigration policies favored by many members of both parties, and he vetoed the Immigration Act of 1917, but Congress overrode the veto. The act, which sought to indirectly reduce immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, imposed literacy tests on immigrants. It was the first U.S. law to restrict immigration from Europe, and it foreshadowed the more restrictive immigration laws of the 1920s.[51]

Home front during World War I

With the American entrance into World War I in April 1917, Wilson became a war-time president. The War Industries Board, headed by Bernard Baruch, was established to set U.S. war manufacturing policies and goals; future President Herbert Hoover lead the Food Administration, to conserve food; the Federal Fuel Administration, run by Henry Garfield, introduced daylight saving time and rationed fuel supplies; William McAdoo was in charge of war bond efforts and Vance McCormick headed the War Trade Board. All of the above, known collectively as the "war cabinet", met weekly with Wilson at the White House.[52] These and other bodies were headed by businessmen recruited by Wilson for a-dollar-a-day salary to make the government more efficient in the war effort.[53]

More favorable treatment was extended to those unions that supported the U.S. war effort, such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Wilson worked closely with Samuel Gompers and the AFL, the railroad brotherhoods, and other 'moderate' unions, which saw enormous growth in membership and wages during Wilson's administration.[54] In the absence of rationing consumer prices soared; income taxes also increased and workers suffered. Despite this, appeals to buy war bonds were highly successful. The purchase of wartime bonds had the result of shifting the cost of the war to the taxpayers of the affluent 1920s.[53]

Antiwar groups, anarchists, communists, Industrial Workers of the World members, and other antiwar groups attempting to sabotage the war effort were targeted by the Department of Justice; many of their leaders were arrested for incitement to violence, espionage, or sedition.[55][56] Wilson also established the first western propaganda office, the United States Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel, the "Creel Commission", which circulated patriotic anti-German appeals and conducted censorship of materials considered seditious.[57] To further counter disloyalty to the war effort at home, Wilson pushed through Congress the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 to suppress anti-British, pro-German, or anti-war statements.[58] While he welcomed socialists who supported the war, he pushed at the same time to arrest and deport foreign-born enemies.[55] Many recent immigrants, resident aliens without U.S. citizenship, who opposed America's participation in the war were deported to Soviet Russia or other nations under the powers granted in the Immigration Act of 1918.[55][56][59]

In an effort at reform and to shake up his Mobilization program, Wilson removed the chief of the Army Signal Corps and the chairman of the Aircraft Production Board on April 18, 1918.[60] On May 16, the President launched an investigation, headed by Republican Charles Evans Hughes, into the War Department and the Council of Defense. The Hughes report released on October 31 found no major corruption violations or theft in Wilson's Mobilization program, although the report found incompetence in the aircraft program.[61]

Wilson's administration did effectively demobilize the country at the war's end. A plan to form a commission for the purpose was abandoned in the face of Republican control the Senate, which complicated the appointment of commission members. Instead, Wilson favored the prompt dismantling of wartime boards and regulatory agencies.[62] Demobilization was chaotic and violent; four million soldiers were sent home with little planning, little money, few benefits, and other vague promises. A wartime bubble in prices of farmland burst, leaving many farmers deeply in debt after they purchased new land. Major strikes in the steel, coal, and meatpacking industries disrupted the economy in 1919.[63]

Prohibition

Prohibition developed as an unstoppable reform during the war, but Wilson played a minor role in its passage.[64] A combination of the temperance movement, hatred of everything German (including beer and saloons), and activism by churches and women led to ratification of an amendment to achieve Prohibition in the United States. A Constitutional amendment passed both houses in December 1917 by 2/3 votes. By January 16, 1919, the Eighteenth Amendment had been ratified by 36 of the 48 states it needed. On October 28, 1919, Congress passed enabling legislation, the National Prohibition Act (informally known as the Volstead Act), to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment. Wilson felt Prohibition was unenforceable, but his veto of the Volstead Act was overridden by Congress.[65] Prohibition began on January 16, 1920 (one year after ratification of the amendment); the manufacture, importation, sale, and transport of alcohol were prohibited, except for limited cases such as religious purposes (as with sacramental wine). But, the consumption of alcohol was never prohibited, and individuals could maintain a private stock that existed before Prohibition went into effect. Wilson moved his private supply of alcoholic beverages to the wine cellar of his Washington residence after his term of office ended.[66][67][68][69]

Wilson's position that nationwide Prohibition was unenforceable came to pass as a black market quickly developed to evade restrictions, and considerable liquor was both manufactured and smuggled into the country. Speakeasies thrived in cities, towns and rural areas. The Eighteenth Amendment was eventually repealed in 1933 with the ratification of the Twenty-First amendment.

Women's suffrage

Wilson favored women's suffrage at the state level. He knew the Southern legislatures were overwhelmingly opposed, and women could get the vote there only through a national constitutional amendment.[70] He held off support for a amendment because his party was sharply divided, with the South opposing an amendment on the grounds of state's rights. Arkansas was the only Southern state to have given women voting rights thus far. From 1917 to 1919, a highly visible campaign by the National Woman's Party (NWP) disparaged Wilson and his party for not enacting any amendment on the matter. Wilson did, however, keep in close touch with the much larger and more moderate suffragists of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. He continued to hold off until he was sure the Democratic Party in the North was supportive; the 1917 referendum in New York State in favor of suffrage proved decisive for him.

In a January 1918 speech before the Congress, Wilson—for the first time endorsed women’s rights to vote. Realizing the vitality of women during the First World War, he asked Congress, "We have made partners of the women in this war… Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?"[71] The House passed a constitutional amendment, but it stalled in the Senate.[72] Wilson continued to speak in its defense, consulting with members of Congress through personal and written appeals, often on his own initiative.[71] Then on June 4, 1919, the proposed amendment prohibiting the states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex,was approved, and submitted it to the state legislatures for ratification.[72] Subsequently ratified by the requisite number of states (then 36) on August 18, 1920, the measure became the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[73] Wilson’s voice proved unequivocal in the ultimate passing of the 19th amendment.[71]

First Red Scare

Following the October Revolution in the Russian Empire, many in America feared the possibility of a Communist-inspired revolution in the United States. These fears were inflamed by the 1919 United States anarchist bombings, which were conducted by the anarchist Luigi Galleani and his followers.[74] In response to such fears, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer launched the Palmer Raids with the intention of capturing and deporting radical activists. Palmer warned of a massive 1920 May Day uprising, but after the day passed by without incident, the Red Scare largely dissipated.[75]

Civil rights

Several historians have criticized a number of Wilson's policies on racial grounds.[76][77][78][79][80][81] In Wilson's first month in office, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson brought up the issue of segregating workplaces in a cabinet meeting and urged the president to establish it across the government, in restrooms, cafeterias and work spaces.[82] Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo also permitted lower-level officials to racially segregate employees in the workplaces of those departments. By the end of 1913 many departments, including the Navy, had workspaces segregated by screens, and restrooms, cafeterias were segregated, although no executive order had been issued.[82] Segregation was urged by such conservative groups as the Fair Play Association.[82]

Wilson defended his administration's segregation policy in a July 1913 letter responding to Oswald Garrison Villard, publisher of the New York Evening Post and founding member of the NAACP; Wilson suggested the segregation removed "friction" between the races.[82] Ross Kennedy says that Wilson complied with predominant public opinion,[83] but his change in federal practices was protested in letters from both blacks and whites to the White House, mass meetings, newspaper campaigns and official statements by both black and white church groups.[82] The president's African-American supporters, who had crossed party lines to vote for him, were bitterly disappointed, and they and Northern leaders protested the changes.[82] Wilson continued to defend his policy, as in a letter to "prominent black minister Rev. H.A. Bridgman, editor of the Congregation and Christian World."[82] Heckscher argues that Wilson had promised African Americans to deal generously with racial injustices, but did not deliver on these assurances.[84] Segregation and government offices, and discriminatory hiring practices had been started by President Theodore Roosevelt and continued by President Taft; The Wilson administration continued and escalated the practice.[85] However, during Wilson's term, the government began requiring photographs of all applicants for federal jobs.[86]

Partly in response to the demand for industrial labor, the Great Migration of African Americans out of the South began in 1917. This migration sparked race riots, including the East St. Louis riots of 1917. In response to these riots, Wilson asked Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory if the federal government could intervene to "check these disgraceful outrages." However, on the advice of Gregory, Wilson did not involve the government in taking action against the riots.[87] Following the end of the war, another series of race riots occurred in Chicago, Omaha, and two dozen other major cities in the North.[88]

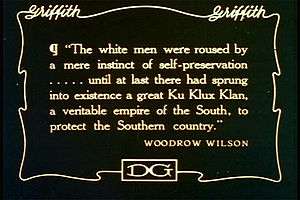

Wilson's War Department drafted hundreds of thousands of blacks into the army, giving them equal pay with whites, but in accord with military policy from the Civil War through the Second World War, kept them in all-black units with white officers, and kept the great majority out of combat.[89] When a delegation of blacks protested the discriminatory actions, Wilson told them "segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen." In 1918, W. E. B. Du Bois—a leader of the NAACP who had campaigned for Wilson believing he was a "liberal southerner"—was offered an Army commission in charge of dealing with race relations; DuBois accepted, but he failed his Army physical and did not serve.[90][91] By 1916, Du Bois opposed Wilson, charging that his first term had seen "the worst attempt at Jim Crow legislation and discrimination in civil service that [blacks] had experienced since the Civil War."[91]

Foreign policy

Wilson's foreign policy was based on an idealistic approach to liberal internationalism standing in sharp contrast to the realistic conservative nationalism of Taft, Roosevelt, and McKinley. Since 1900, the consensus of Democrats had, according to Arthur Link:

- consistently condemned militarism, imperialism, and interventionism in foreign policy. They instead advocated world involvement along liberal-internationalist lines. Wilson's appointment of William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State indicated a new departure, for Bryan had long been the leading opponent of imperialism and militarism and a pioneer in the world peace movement.[92]

Bryan took the initiative in asking 40 countries with ambassadors in Washington to sign bilateral arbitration treaties. Any dispute of any kind with the United States would lead to a one-year cooling-off period, and submission to an international commission for arbitration. Thirty countries signed, but not Mexico and Colombia (which had grievances with Washington), nor Japan, Germany, Austria-Hungary or the Ottoman Empire. European diplomats signed the treaties, but considered them irrelevant.[93]

Diplomatic historian George C. Herring says that Wilson's idealism was genuine, but that it was structured by blind spots:

- Wilson’s genuine and deeply felt aspirations to build a better world suffered from a certain culture-blindness. He lacked experience in diplomacy and hence an appreciation of its limits. He had not traveled widely outside the United States and knew little of other peoples and cultures beyond Britain, which he greatly admired. Especially in his first years in office, he had difficulty seeing that well-intended efforts to spread U.S. values might be viewed as interference at best, coercion at worst. His vision was further narrowed by the terrible burden of racism, common among the elite of his generation, which limited his capacity to understand and respect people of different colors. Above all, he was blinded by his certainty of America’s goodness and destiny.[94]

Mexican Revolution

Wilson took office during the Mexican Revolution and shortly after the assassination of Francisco I. Madero, the President of Mexico from 1911 to 1913. Wilson rejected the legitimacy of Victoriano Huerta's "government of butchers" and demanded Mexico hold democratic elections. Wilson's unprecedented approach meant no recognition and doomed Huerta's prospects. Wilsonian idealism became a reason for American intervention in Latin America until 1933, when Franklin Roosevelt ended moralistic approaches to the region.[95] After Huerta arrested U.S. Navy personnel in the port of Tampico Wilson sent his navy to occupy Veracruz.[96] War between the United States and Mexico was averted through negotiations, and in 1916 his reelection campaign for president boasted he had "kept us out of war". Huerta fled Mexico and Venustiano Carranza came to power.[97] Though the administration had achieved the desired result, it was Carranza's lieutenant, Pancho Villa, who presented a more serious threat in 1916.[98]

In early 1916 Pancho Villa raided an American town in New Mexico, killing or wounding dozens of Americans and causing an enormous nationwide American demand for his punishment. Wilson ordered Gen. John Pershing and 4000 troops across the border to capture Villa. By April, Pershing's forces had broken up and dispersed Villas bands. Villa remained on the loose and Pershing continued his pursuit deep into Mexico. Carranza then pivoted against the Americans and accused them of a punitive invasion; a confrontation with a mob in Parral on April 12 resulted in two dead Americans and six wounded, plus hundreds of Mexican casualties. Further incidents led to the brink of war by late June when Wilson demanded an immediate release of American soldiers held prisoner. They were released; tensions subsided and bilateral negotiations began under the auspices of the Mexican-American Joint High Commission. In early 1917, as tensions with Germany escalated toward war. Unknown to Washington, Germany's Zimmermann Telegram had already invited Mexico to join in war against the United States. Wilson had to get out of Mexico to deal with Germany and he ordered Pershing to withdraw from Mexico. The last American soldiers left on February 5, 1917. The Americans learned of the Zimmermann proposal on February 23, and Wilson accorded Carranza diplomatic recognition in April, after war was declared on Germany. Biographer Arthur Link calls it Carranza's victory—his successful handling of the chaos inside Mexico, as well as over Wilson's policies. Mexico was now free to develop its revolution without American pressure.[99]

The chase after Pancho Villa was a small military episode, but it had important long-term implications. It enabled Carranza to mobilize popular anger, strengthen his political position, and permanently escalate anti-American sentiment in Mexico.[100] On the American side, it made Pershing a national figure and led to Wilson choosing him to command the American forces in France in 1917–1918. The expedition involved 15,000 American regulars; some 110,000 part-time soldiers of the National Guard were activated to serve border duty inside the United States. It gave the American army some needed experience in dealing with training, planning and logistics. Most importantly, it highlighted serious weaknesses in the National Guard in terms of training, recruiting, planning, and ability to mobilize quickly.[101] It gave the American public a way to work out its frustrations over the European stalemate and it showed that the United States was willing to defend its borders while keeping that demonstration on a small scale.[102]

Latin America

Wilson sought closer relations with Latin America, and he hoped to create a Pan-American organization to arbitrate international disputes. He also negotiated a treaty with Colombia that would have paid that country an indemnity for the U.S. role in the Separation of Panama from Colombia, but the Senate defeated this treaty.[103] However, Wilson frequently intervened in Latin American affairs, saying in 1913: "I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men."[104] The Dominican Republic had been a de facto American protectorate since Roosevelt's presidency, but suffered from instability. In 1916, Wilson sent troops to occupy the island, and the U.S. soldiers would remain until 1924. In 1915, the U.S. intervened in Haiti after a revolt overthrew the Haitian government, beginning an occupation that would last until 1919. Wilson also authorized military interventions in Cuba, Panama, and Honduras. The 1914 Bryan–Chamorro Treaty converted Nicaragua into another de facto protectorate, and the U.S. stationed soldiers there throughout Wilson's presidency.[105]

The Panama Canal opened in 1914, fulfilling the long-term American goal of building a canal across Central America. The canal provided relatively swift passage between the Pacific Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean, presenting new economic opportunities to the U.S. and allowing the U.S. Navy to quickly navigate between the two oceans. In 1916, Wilson signed the Treaty of the Danish West Indies, in which the United States acquired the Danish West Indies for $2 million. After the purchase, the islands were re-named as the United States Virgin Islands.

Neutrality in the World War

Americans had no inkling that a war was approaching in 1914. Over 100,000 were caught unawares when the war started, having traveled to Europe for tourism, business or to visit relatives. Their repatriation was handled by Herbert Hoover, an American private citizen based in London. The U.S. government, under the firm control of President Wilson, was neutral. The president insisted that all government actions be neutral, and that the belligerents must respect that neutrality according to the norms of international law. Wilson told the Senate in August 1914 when the war began that the United States, "must be impartial in thought as well as in action, must put a curb upon our sentiments as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another." He was ambiguous whether he meant the United States as a nation or meant all Americans as individuals. [106] Wilson has been accused of violating his own rule of neutrality. Later that month he explained himself privately to his top foreign policy advisor Colonel House, who recalled the episode later:

- I was interested to hear him express as his opinion what I had written him some time ago in one of my letters, to the effect that if Germany won it would change the course of our civilization and make the United States a military nation. He also spoke of his deep regret, as indeed I did to him in that same letter, that it would check his policy for a better international ethical code. He felt deeply the destruction of Louvain [in Belgium], and I found him as unsympathetic with the German attitude as is the balance of America. He goes even further than I in his condemnation of Germany's part in this war, and almost allows his feeling to include the German people as a whole rather than the leaders alone. He said German philosophy was essentially selfish and lacking in spirituality. When I spoke of the Kaiser building up the German machine as a means of maintaining peace, he said, "What a foolish thing it was to create a powder magazine and risk someone's dropping a spark into it!" He thought the war would throw the world back three or four centuries. I did not agree with him. He was particularly scornful of Germany’s disregard of treaty obligations, and was indignant at the German Chancellor’s designation of the Belgian Treaty as being "only a scrap of paper"....But although the personal feeling of the President was with the Allies, he insisted then and for many months after, that this ought not to affect his political attitude, which he intended should be one of strict neutrality. He felt that he owed it to the world to prevent the spreading of the conflagration, that he owed it to the country to save it from the horrors of war.[107]

Apart from an Anglophile element supporting Britain, public opinion in 1914-1916 strongly favored neutrality. Wilson kept the economy on a peacetime basis, and made no preparations or plans for the war. He insisted on keeping the army and navy on its small peacetime bases. Indeed, Washington refused even to study the lessons of military or economic mobilization that had been learned so painfully across the sea.[108]

From 1914 until early 1917, Wilson's primary objective was to keep the United States out of the war in Europe, and his policy was, "the true spirit of neutrality, which is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned."[109] The Great War in Europe pitted the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria) against the Allied Powers (Great Britain, France, Russia and several other countries). In a 1914 address to Congress, Wilson emphasized the American role as honest broker for peace: "Such divisions amongst us would be fatal to our peace of mind and might seriously stand in the way of the proper performance of our duty as the one great nation at peace, the one people holding itself ready to play a part of impartial mediation and speak the counsels of peace and accommodation, not as a partisan, but as a friend."[110] He made numerous offers to mediate and sent Colonel House on diplomatic missions; the Allies and the Central Powers, however, dismissed these overtures. Wilson even thought it counterproductive to comment on atrocities by either side; this led to assertions of heartlessness on his part.[111] Interventionists, led by Theodore Roosevelt, wanted war with Germany and attacked Wilson's refusal to build up the U.S. Army in anticipation of war.[112]

When Britain declared a blockade of neutral ships carrying contraband goods to Germany, Wilson mildly protested non-lethal British violations of neutral rights; the British knew that it would not be a casus belli for the United States.[113] In early 1915 Germany declared the waters around Great Britain to be a war zone; Wilson dispatched a note of protest, imposing "strict accountability" on Germany for the safety of neutral ships. The meaning of the policy, dubiously applied to specific incidents, evolved with the policy of neutrality, but ultimately formed the substance of U.S. responses over the next two years.[114] The commercial British steamship Falaba was sunk in March 1915 by a German submarine with the loss of 111 lives, including one American in the Thrasher Incident. Wilson chose to avoid risking escalation of the war as a result of the loss of one American.[114] In the spring of 1915 a German bomb struck an American ship, the Cushing and a German submarine torpedoed an American tanker, the Gulflight. Wilson took the view, based on some reasonable evidence, that both incidents were accidental, and that a settlement of claims could be postponed to the end of the war.[115]

A German submarine torpedoed and sank the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania in May 1915; over a thousand perished, including many Americans. In a Philadelphia speech that weekend Wilson said, "There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right". Many reacted to these remarks with contempt.[116] Wilson sent a subdued note to the Germans protesting its submarine warfare against commerce; the initial reply was evasive and received in the United States with indignation. Secretary of State Bryan, a dedicated pacifist, sensing the country's path to war, resigned, and was replaced by Robert Lansing. The White Star liner the SS Arabic was then torpedoed, with two American casualties. The U.S. threatened a diplomatic break unless Germany repudiated the action; the German ambassador then conveyed a note, "liners will not be sunk by our submarines". Wilson had not stopped the submarine campaign, but won agreement that unarmed merchant ships would not be sunk without warning; and most importantly he had kept the U.S. out of the war.[117] Meanwhile, Wilson requested and received funds in the final 1916 appropriations bill to provide for 500,000 troops. It also included a five-year Navy plan for major construction of battleships, cruisers, destroyers and submarines—showing Wilson's dedication to a big Navy.[118]

In March 1916 the SS Sussex, an unarmed ferry under the French flag, was torpedoed in the English Channel and four Americans were counted among the dead; the Germans had flouted the post-Lusitania exchanges. The president demanded the Germans reject their submarine tactics.[119] Wilson drew praise when he succeeded in wringing from Germany a pledge to constrain their U-boat warfare to the rules of cruiser warfare. This was a clear departure from existing practices—a diplomatic concession from which Germany could only more brazenly withdraw, and regrettably did.[120]

Wilson made a plea for postwar world peace in May 1916; his speech recited the right of every nation to its sovereignty, territorial integrity and freedom from aggression. "So sincerely do we believe these things", Wilson said, "that I am sure that I speak the mind and wish of the people of America when I say that the United States is willing to become a partner in any feasible association of nations formed in order to realize these objectives". At home the speech was seen as a turning point in policy. In Europe the words were received by the British and the French without comment. His harshest European critics rightly thought the speech reflected indifference on Wilson's part; indeed, Wilson never wavered from a belief that the war was the result of corrupt European power politics.[121]

Wilson made his final offer to mediate peace on December 18, 1916. As a preliminary, he asked both sides to state their minimum terms necessary for future security. The Central Powers replied that victory was certain, and the Allies required the dismemberment of their enemies' empires; no desire for peace existed, and the offer lapsed.[122]

Wilson found it increasingly difficult to maintain neutrality, after Germany rescinded earlier promises—the Arabic pledge and the Sussex pledge. Early in 1917 the German ambassador Johann von Bernstorf informed Secretary of State Lansing of Germany's commitment to unrestricted submarine warfare; Bernstorff had tears in his eyes as he knew the U.S. reaction would adversely affect his country's lot.[123] Then came the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram, in which Germany attempted to enlist Mexico as an ally, promising Mexico that if Germany was victorious, she would support Mexico in winning back the states of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona from the U.S.[124] Wilson's reaction after consulting the cabinet and the Congress was a minimal one—that diplomatic relations with the Germans be brought to a halt. The president said, "We are the sincere friends of the German people and earnestly desire to remain at peace with them. We shall not believe they are hostile to us unless or until we are obliged to believe it".[125] In March 1917 several American ships were sunk by Germany and Teddy Roosevelt privately reacted, "if he does not go to war I shall skin him alive".[126] Wilson called a cabinet meeting on March 20, in which the vote was unanimously in support of entering the war.[127]

Preparedness

The Great War in Europe stalemated in 1914, and escalated in terms of bloodshed on the Western Front. American policy was to stay out, but at the same time military preparedness in terms of readiness to enter the war became a major dimension of public opinion.[128] , as reflected by Republican leaders, especially Roosevelt, most leading newspapers and the leaders of the business and financial communities. New, well-funded organizations sprang up to appeal to the grassroots, including the American Defense Society (ADS) and the National Security League.[129][130] Wilson resisted the demands, delayed and postponed, for there was a powerful anti-preparedness element of the party, led by Bryan, women,[131] Protestant churches,[132] the AFL labor unions,[133] and Southern Democrats such as Claude Kitchin, chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee. Biographer John Morton Blum says:

- Wilson's long silence about preparedness had permitted such a spread and such a hardening of antipreparedness attitudes within his party and across the nation that when he came in at late last to his task, neither Congress to the country was amenable to much persuasion.[134]

In July 1915 Wilson instructed the Army and Navy to formulate plans for expansion, in November he asked for far less than the experts said was needed, seeking an army of 400,000 volunteers at a time when European armies were 10 times as large. Congress ignored proposal in the Army to remained at 100,000 soldiers. Wilson was severely handicapped by the weaknesses of his cabinet: his secretaries of War and Navy, says Blum, displayed a, "confusion, inattention to industrial preparation, and excessive deference to peacetime mores [that] dangerously retarded the development of the armed services."[135] Even more Wilson was constrained by America's traditional commitment to military nonintervention. Wilson believed that a massive military mobilization could only take place after a declaration of war, even though that meant a long delay in sending troops to Europe. Many Democrats felt that no American soldiers would be needed, only American money and munitions. [136] Wilson had more success in his request for a dramatic expansion of the Navy. Congress passed a Naval Expansion Act in 1916 That encapsulated the planning by the Navy's professional officers to build a fleet of top-rank status, but it would take several years to become operational.[137]

World War I

Wilson delivered his War Message to a special session of Congress on April 2, 1917, declaring that Germany's latest pronouncement had rendered his "armed neutrality" policy untenable and asking Congress to declare Germany's war stance was an act of war.[138] He proposed the United States enter the war to "vindicate principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power". The German government, Wilson said, "means to stir up enemies against us at our very doors". He then also warned that "if there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with a firm hand of repression."[58] Wilson closed with:

Our object...is to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power....We are glad...to fight...for the ultimate peace of the world and for the liberation of its peoples, the German peoples included: for the right of nations great and small and the privilege of men everywhere to choose their way of life and of obedience. The world must be made safe for democracy....We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make.[139]

The declaration of war by the United States against Germany passed Congress by strong bipartisan majorities on April 4, 1917, with opposition from ethnic German strongholds and remote rural areas in the South. It was signed by Wilson on April 6, 1917. The United States would also later declare war against Austria-Hungary in December 1917. The U.S. did not sign a formal alliance with Britain or France but operated as an "associated" power—an informal ally with military cooperation through the Supreme War Council in London.[140] The U.S. raised a massive army through conscription and Wilson gave command to General John J. Pershing, with complete authority as to tactics, strategy and some diplomacy.[141] Edward M. House, Wilson's key unofficial foreign affairs advisor, became the president's main channel of communication with the British government, and William Wiseman, a British naval attaché, was House's principal contact in England. Their personal relationship succeeded in serving the powers well, by overcoming strained relations in order to achieve essential understandings between the two governments. House also became the U.S. representative on the Allies' Supreme War Council.[142]

March 1917 also brought the first of two revolutions in Russia, which impacted the strategic role of the U.S. in the war. The overthrow of the imperial government removed a serious barrier to America's entry into the European conflict, while the second revolution in November relieved the Germans of a major threat on their eastern front, and allowed them to dedicate more troops to the Western front, thus making U.S. forces central to Allied success in battles of 1918. Wilson initially rebuffed pleas from the Allies to dedicate military resources to an intervention in Russia against the Bolsheviks, based partially on his experience from attempted intervention in Mexico; nevertheless he ultimately was convinced of the potential benefit and agreed to dispatch a limited force to assist the Allies on the eastern front.[143]

The Germans launched an offensive at Arras which prompted an accelerated deployment of troops by Wilson to the Western front—by August 1918 a million American troops had reached France. The Allies initiated a counter offensive at Somme and by August the Germans had lost the military initiative and an Allied victory was in sight. In October came a message from the new German Chancellor Prince Max of Baden to Wilson requesting a general armistice. In the exchange of notes with Germany they agreed the Fourteen Points in principle be incorporated in the armistice; House then procured agreement from France and Britain, but only after threatening to conclude a unilateral armistice without them. Wilson ignored Gen. Pershing's plea to drop the armistice and instead demand an unconditional surrender by Germany.[144]

The Germans signed the Armistice of 11 November 1918, bringing an end to the fighting. Austria-Hungary had signed the Armistice of Villa Giusti eight days earlier, while the Ottoman Empire had signed the Armistice of Mudros in October. The combatants would meet at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference to set the peace terms.

The Fourteen Points

Wilson initiated a secret series of studies named The Inquiry, primarily focused on Europe, and carried out by a group in New York which included geographers, historians and political scientists; the group was directed by Col. House.[145] The studies culminated in a speech by Wilson to Congress on January 8, 1918, wherein he articulated America's long term war objectives. It was the clearest expression of intention made by any of the belligerent nations. The speech, known as the Fourteen Points, was authored mainly by Walter Lippmann and projected Wilson's progressive domestic policies into the international arena. The first six dealt with diplomacy, freedom of the seas and settlement of colonial claims. Then territorial issues were addressed and the final point, the establishment of an association of nations to guarantee the independence and territorial integrity of all nations—a League of Nations. The address was translated into many languages for global dissemination.[146]

Aside from post-war considerations, Wilson's Fourteen Points were motivated by several factors. Unlike some of the other Allied leaders, Wilson did not call for a break-up of the Ottoman Empire or the Austro-Hungarian Empire, nor did he call for self-determination throughout Europe. In offering a non-punitive peace to these nations as well as Germany, Wilson hoped to quickly began negotiations to end the war. Wilson's liberal pronouncements were also targeted at pacifistic and war-weary elements within the Allied countries, including the United States. Additionally, Wilson hoped to woo the Russians back into the war, although in this he failed, as the Russians left the war with the signing of the March 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.[147]

Paris Peace Conference

After the signing of the armistice, Wilson traveled to Europe to attend the Paris Peace Conference, thereby becoming the first U.S. president to travel to Europe while in office.[148] Save for a two-week return to the United States, Wilson remained in Europe for six months, where he focused on a peace treaty to formally end the war. The defeated Central Powers had not been invited to the conference, and anxiously awaited their fate. Though Wilson continued to advocate his idealistic Fourteen Points, many of the other allies desired revenge. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau especially sought onerous terms for Germany, while British Prime Minister David Lloyd George supported some of Wilson's ideas but feared public backlash if the treaty proved too favorable to the Central Powers. Wilson, Lloyd George, Clemenceau, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando made up the "Big Four," the Allied leaders with the most influence at the Paris Peace Conference.[149]

In pursuit of his League of Nations, Wilson conceded several points to the other powers present at the conference. France pressed for the dismemberment of Germany and the payment of a huge sum in war reparations. Wilson resisted these ideas, but Germany was still required to pay war reparations and subjected to military occupation, and a clause in the treaty specifically named Germany as responsible for the war. Wilson also agreed to the creation of mandates in former German and Ottoman territories, allowing the European powers and Japan to establish de facto colonies in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. The Japanese acquisition of German interests in the Shandong Peninsula of China proved especially unpopular, as it undercut Wilson's promise of self-government. However, Wilson won the creation of several new states in Central Europe and the Balkans, including Poland, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire were partitioned.[150] Japan proposed that the conference endorse a racial equality clause. Wilson was indifferent to the issue, but acceded to strong opposition from Australia and Britain.[151]

The charter of Wilson's proposed League of Nations was incorporated into the conference's Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war with Germany.[152] The Allies also wrote treaties with Austria (the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye), Hungary (the Treaty of Trianon), the Ottoman Empire (the Treaty of Sèvres), and Bulgaria (the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine), all of which incorporated the League of Nations charter. During the conference, Taft cabled to Wilson three proposed amendments to the League covenant which he thought would considerably increase its acceptability to the Europeans—the right of withdrawal from the League, the exemption of domestic issues from the League and the inviolability of the Monroe Doctrine. Wilson very reluctantly accepted these amendments, explaining why he later was more inflexible in the Senate treaty negotiations.[153] After the conference, Wilson said that "at last the world knows America as the savior of the world!"[154]

For his peace-making efforts, Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize.[155] However, the defeated Central Powers protested the harsh terms of the treaty, while several colonial representatives pointed out the hypocrisy of a treaty that established new nations in Europe but allowed continued colonialism in Asia and Africa. Wilson also faced an uncertain domestic battle to ratify the treaty, as Republicans largely opposed it.[156]

Treaty fight

The chances were less than favorable for ratification of the treaty by a two-thirds vote of the Republican Senate. Public opinion was mixed, with intense opposition from most Republicans, Germans, and Irish Catholic Democrats. In numerous meetings with Senators, Wilson discovered opposition had hardened. Despite his weakened physical condition following the Paris Peace Conference, Wilson decided to barnstorm the Western states, scheduling 29 major speeches and many short ones to rally support.[157] Wilson suffered a series of debilitating strokes and had to cut short his trip on in September 1919. He became an invalid in the White House, closely monitored by his wife, who insulated him from negative news and downplayed for him the gravity of his condition.[158]

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge led the opposition to the treaty; he despised Wilson and hoped to humiliate him in the ratification battle. Republicans were outraged by Wilson's failure to discuss the war or its aftermath with them. An intensely partisan battle developed in the Senate, as Republicans opposed the treaty and Democrats largely supported it. The debate over the treaty centered around a debate over the American role in the world community in the post-war era, and Senators fell into three main groups, with one group strongly supporting Wilson's proposals. Fourteen Senators, mostly Republicans, become known as the "irreconcilables," as they completely U.S. entrance into the League of Nations. Some of these irreconcilables, such as George W. Norris, opposed the treaty for its failure to support decolonization and disarmament. Other irreconcilables, such as Hiram Johnson, feared surrendering American freedom of action to an international organization. Many Senators, known as "reservationists," accepted the idea of the league, but sought varying degrees of change to the League to ensure the protection of U.S. sovereignty. Most sought the removal of Article X the League covenant, which purported to bind nations to defend each other against aggression. Most Republicans, including Lodge, were reservationists.[159]

In mid-November 1919, Lodge and his Republicans formed a coalition with the pro-treaty Democrats, and were close to a two-thirds majority for a treaty with reservations, but the seriously indisposed Wilson rejected this compromise and enough Democrats followed his lead to defeat ratification. Cooper and Bailey suggest that Wilson's stroke in September had debilitated him from negotiating effectively with Lodge.[160] U.S. involvement in World War I would not formally end until the passage of the Knox–Porter Resolution in 1921.

Intervention in Russia

After Russia left World War I following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the Allies sent troops there to prevent a German or Bolshevik takeover of allied-provided weapons, munitions and other supplies previously shipped as aid to the pre-revolutionary government.[161] Wilson loathed the Bolsheviks, who he believed did not represent the Russian people, and feared that foreign intervention would only strengthen Bolshevik rule. His allies pressured him to intervene in order to potentially re-open a second front against Germany, and Wilson acceded to this pressure in the hope that it would help him in post-war negotiations and check Japanese influence in Siberia.[162] The U.S. sent armed forces to assist the withdrawal of Czechoslovak Legions along the Trans-Siberian Railway, and to hold key port cities at Arkhangelsk and Vladivostok. Though specifically instructed not to engage the Bolsheviks, the U.S. forces engaged in several armed conflicts against forces of the new Russian government. Revolutionaries in Russia resented the United States intrusion. Robert Maddox wrote, "The immediate effect of the intervention was to prolong a bloody civil war, thereby costing thousands of additional lives and wreaking enormous destruction on an already battered society."[163] Wilson withdrew most of the soldiers on April 1, 1920, though some remained until as late as 1922.

Other foreign affairs

In 1919, Wilson guided American foreign policy to "acquiesce" in the Balfour Declaration without supporting Zionism in an official way. Wilson expressed sympathy for the plight of Jews, especially in Poland and France.[164]

In May 1920, Wilson sent a long-deferred proposal to Congress to have the U.S. accept a mandate from the League of Nations to take over Armenia.[165] Bailey notes this was opposed by American public opinion,[166] while Richard G. Hovannisian states that Wilson "made all the wrong arguments" for the mandate and focused less on the immediate policy than on how history would judge his actions: "[he] wished to place it clearly on the record that the abandonment of Armenia was not his doing."[167] The resolution won the votes of only 23 senators.

List of international trips

Wilson made one international trip while president–elect and two during his presidency.[168] Wilson was the first sitting president to travel to Europe. He spent nearly seven months in Europe after World War I (interrupted by a brief 9-day return stateside).

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | November 18 – December 13, 1912 | Vacation. (Visit made as President-elect.) | ||

| 2 | December 14–25, 1918 | Paris, Chaumont |

Attended preliminary discussions prior to the Paris Peace Conference; promoted his Fourteen Points principles for world peace. Departed the U.S. December 4. | |

| December 26–31, 1918 | London, Carlisle, Manchester |

Met with Prime Minister David Lloyd George and King George V. | ||

| December 31, 1918 – January 1, 1919 | Paris | Stopover en route to Italy. | ||

| January 1–6, 1919 | Rome, Genoa, Milan, Turin |

Met with King Victor Emmanuel III and Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. | ||

| January 4, 1919 | Rome | Audience with Pope Benedict XV. | ||

| January 7–14, 1919 | Paris | Attended Paris Peace Conference. Arrived In the U.S. February 24. | ||

| 3 | March 14 – June 18, 1919 | Paris | Attended Paris Peace Conference. Departed the U.S. March 5. | |

| June 18–19, 1919 | Brussels, Charleroi, Malines, Louvain |

Met with King Albert I. Addressed Parliament. | ||

| June 20–28, 1919 | Paris | Attended Paris Peace Conference. Returned to U.S. July 8. |

Incapacity, 1919–1920

In September 1919, while on a public speaking tour in support of the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson collapsed and never fully recovered. In 1906 Wilson had first exhibited arterial hypertension, mainly untreatable at the time.[169] During his presidency, he had repeated episodes of unexplained arm and hand weakness, and his retinal arteries were said to be abnormal on fundoscopic examination.[170] He developed severe headaches, diplopia (double vision), and evanescent weakness of the left arm and leg. In retrospect, physicians have said that those problems likely represented the effects of cerebral transient ischemic attacks.[171] On October 2, 1919, Wilson suffered a serious stroke, leaving him paralyzed on his left side, and with only partial vision in the right eye.[172] He was confined to bed for weeks and sequestered from everyone except his wife and physician, Dr. Cary Grayson.[173] For some months Wilson used a wheelchair and later he required use of a cane. His wife and aide Joe Tumulty were said to have helped a journalist, Louis Seibold, present a false account of an interview with the President.[174]

Despite his health problems, Wilson rarely considered resigning, and he continued to advocate ratification of the Treaty of Versailles.[175] Wilson was insulated by his wife, who selected matters for his attention and delegated others to his cabinet. Wilson temporarily resumed a perfunctory attendance at cabinet meetings.[176] By February 1920, the president's true condition was publicly known. Many expressed qualms about Wilson's fitness for the presidency at a time when the League fight was reaching a climax, and domestic issues such as strikes, unemployment, inflation and the threat of Communism were ablaze. No one close to him, including his wife, his physician, or personal assistant, was willing to take responsibility to certify, as required by the Constitution, his "inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office".[177] Though some members of Congress encouraged Vice President Marshall to assert his claim to the presidency, Marshall never attempted to replace Wilson.[24] Wilson's lengthy period of incapacity while serving as president was nearly unprecedented; of the previous presidents, only James Garfield had been in a similar situation, but Garfield retained greater control of his mental faculties and faced relatively few pressing issues.[178] In 1967, the U.S. would ratify 25th Amendment to control succession to the presidency in case of illness.[179]

Elections during the Wilson presidency

Midterm elections of 1914

In Wilson's first mid-term elections, Republicans picked up sixty seats in the House, but failed to re-take the chamber. In the first Senate elections since the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment, Democrats retained their Senate majority. Roosevelt's Bull Moose Party, which had won a handful of Congressional seats in the 1912 election, fared poorly, while conservative Republicans also defeated several progressive Republicans. The continuing Democratic control of Congress pleased Wilson, and he publicly argued that the election represented a mandate for continued progressive reforms.[180]

Presidential election of 1916

Wilson, renominated without opposition, employed his campaign slogan "He kept us out of war", though he never promised unequivocally to stay out of the war. In his acceptance speech on September 2, 1916, Wilson pointedly warned Germany that submarine warfare resulting in American deaths would not be tolerated, saying "The nation that violates these essential rights must expect to be checked and called to account by direct challenge and resistance. It at once makes the quarrel in part our own."[181]

Vance C. McCormick, a leading progressive, became chairman of the party, and Ambassador Henry Morgenthau was recalled from Turkey to manage campaign finances.[182] "Colonel" House played an important role in the campaign. "He planned its structure; set its tone; helped guide its finance; chose speakers, tactics, and strategy; and, not least, handled the campaign's greatest asset and greatest potential liability: its brilliant but temperamental candidate."[183]

As the Party platform was drafted, Senator Owen of Oklahoma urged Wilson to take ideas from the Progressive Party platform of 1912 "as a means of attaching to our party progressive Republicans who are in sympathy with us in so large a degree." At Wilson's request, Owen highlighted federal legislation to promote workers' health and safety, prohibit child labour, provide unemployment compensation and establish minimum wages and maximum hours. Wilson, in turn, included in his draft platform a plank that called for all work performed by and for the federal government to provide a minimum wage, an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child labour, and (his own additions) safeguards for female workers and a retirement program.[184]

Wilson's opponent was Republican Charles Evans Hughes, former governor of New York with a progressive record similar to Wilson's as governor of New Jersey. Theodore Roosevelt commented that the only thing different between Hughes and Wilson was a shave. However, Hughes had to try to hold together a coalition of conservative Taft supporters and progressive Roosevelt partisans, and his campaign never assumed a definite form. Wilson ran on his record and ignored Hughes, reserving his attacks for Roosevelt. When asked why he did not attack Hughes directly, Wilson told a friend, "Never murder a man who is committing suicide."[185]

The election outcome was in doubt for several days and was determined by several close states. Wilson won California by 3,773 of almost a million votes cast, and New Hampshire by 54 votes. Hughes won Minnesota by 393 votes out of over 358,000. In the final count, Wilson had 277 electoral votes vs. Hughes's 254. Wilson was able to win by picking up many votes that had gone to Teddy Roosevelt or Eugene V. Debs in 1912.[186] By the time Hughes' concession telegram arrived, Wilson commented "it was a little moth-eaten when it got here".[187] Wilson's re-election made him the first Democrat since Andrew Jackson to win two consecutive terms. Wilson's party also maintained control of Congress, although control in the House would depend on the support of several members of the Progressive Party.[188]

Midterm elections of 1918

Wilson involved himself in the 1918 Democratic congressional primaries, hoping to elect progressive members of Congress who would support his administration's foreign policies. Wilson succeeded in defeating several intra-party opponents, including Senator James K. Vardaman of Mississippi.[189] However, the general elections saw Republicans take control of both the House and the Senate. Republicans ran against Wilson's foreign policy agenda, especially his proposal for the League of Nations.[190]

Presidential election of 1920

Despite his ill health, Wilson continued to entertain the possibility of running for a third term. Many of Wilson's advisers tried to convince him that his health precluded another campaign, but Wilson asked Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby to nominate Wilson as the 1920 Democratic National Convention. While the convention strongly endorsed Wilson's policies, Democratic leaders were unwilling to support the ailing Wilson for a third term. The convention held several ballots over multiple days, with McAdoo and Governor James Cox of Ohio emerging as the major contenders for the nomination. After dozens of ballots, the convention eventually nominated a ticket consisting of Cox and Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy.[191]

Theodore Roosevelt was widely expected to be the 1920 Republican nominee until his death in January 1919, leaving the race for the Republican nomination wide open.[192] The 1920 Republican National Convention instead nominated Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio and Governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts. The Republicans centered their campaign around opposition to Wilson's policies, with Harding promising a "return to normalcy" to the conservative policies that had prevailed at the turn of the century. Wilson largely stayed out of the campaign, although he endorsed Cox and continued to advocate for U.S. membership in the League of Nations. Harding won a landslide victory, taking 60.3% of the popular vote and winning every state outside of the South. Democrats also suffered huge losses in the Congressional and gubernatorial elections of 1920, and the Republicans increased their majorities in both houses of Congress.[193]

Legacy

Wilson is generally ranked by historians and political scientists as one of better presidents.[194] More than any of his predecessors, Wilson took steps towards the creation of a strong federal government that would protect ordinary citizens against the overwhelming power of large corporations.[195] Many of Wilson's accomplishments, including the Federal Reserve, the Federal Trade Commission, the graduated income tax, and labor laws, continued to influence the United States long after Wilson's death.[194] He is generally regarded as a key figure in the establishment of Modern American liberalism who influenced future presidents such as Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson.[194] Cooper argues that in terms of impact and ambition, only the New Deal and the Great Society rival the domestic accomplishments of Wilson's presidency.[196] Wilson's idealistic foreign policy, which came to be known as Wilsonianism, also cast a long shadow over American foreign policy, and Wilson's League of Nations influenced the development of the United Nations. However, Wilson's record on civil rights has often been attacked.[194] Wilson's administration saw a new level of segregation among the federal government, and Wilson's Cabinet included several racists.[194]

References

- ↑ William Keylor, "The long-forgotten racial attitudes and policies of Woodrow Wilson", March 4, 2013, Professor Voices, Boston University, accessed March 10, 2016

- ↑ Blum, John Morton (1956). Woodrow Wilson and the Politics of Morality. Boston: Little, Brown.

- ↑ Gamble, Richard M. (2001). "Savior Nation: Woodrow Wilson and the Gospel of Service" (PDF). Humanitas. 14 (1): 4–22.

- ↑ Cooper, Woodrow Wilson (2009) p. 560.

- ↑ Cooper (2009), pp. 140–141