Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

| ||

|---|---|---|

President of the United States First Term Second Term Third Term

Fourth Term |

||

The presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt began on March 4, 1933, when he was inaugurated as the 32nd President of the United States, and ended upon his death on April 12, 1945, a span of 12 years, 39 days (4422 days).[lower-alpha 1] Roosevelt assumed the presidency in the midst of the Great Depression. Starting with his landslide victory over Republican President Herbert Hoover in the 1932 election. He won a record four presidential terms, and became a central figure in world affairs during World War II. His program for relief, recovery and reform, known as the New Deal, involved a great expansion of the role of the federal government in the economy. Under his steady leadership, the Democratic Party built a "New Deal Coalition" of labor unions, big city machines, white ethnics, African Americans, and rural white Southerners, that would significantly realign American politics for the next several decades in the Fifth Party System and also define modern American liberalism.

During his first hundred days in office, Roosevelt spearheaded unprecedented major legislation and issued a profusion of executive orders that instituted the New Deal—a variety of programs designed to produce relief (government jobs for the unemployed), recovery (economic growth), and reform (through regulation of Wall Street, banks and transportation). He created numerous programs to support the unemployed and farmers, and to encourage labor union growth while more closely regulating business and high finance. The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 added to his popularity, helping him win re-election by a landslide in 1936. The economy improved rapidly from 1933 to 1937, but then relapsed into a deep recession in 1937–38. The bipartisan Conservative Coalition that formed in 1937 prevented his attempted packing of the Supreme Court, and blocked most of his legislative proposals, aside from the Fair Labor Standards Act. When the war began and unemployment largely became a non-issue, conservatives in Congress repealed the two major relief programs, the WPA and CCC, but kept most of the regulations on business. Along with several smaller programs, major surviving programs from the New Deal include the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the Wagner Act, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Social Security.

A potential worldwide war loomed after 1937, with the Japanese invasion of China and the aggression of Nazi Germany, which invaded Poland in September 1939. Roosevelt remained officially neutral but gave strong diplomatic and financial support to China, the United Kingdom, Free France, and the Soviet Union via initiatives such as the Lend-Lease programs. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Roosevelt sought and obtained a declaration of war upon Japan. A few days later, he sought and obtained a declaration of war upon the other major Axis powers, Germany and Italy. Assisted by his top aide Harry Hopkins, and with very strong national support, he worked closely with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in leading the Allies during World War II. He supervised the mobilization of the U.S. economy to support the war effort, and the war saw the end of the massive unemployment that characterized the Great Depression. Roosevelt sought to desegregate the federal workforce with the Fair Employment Practice Committee, but he also controversially ordered the internment of 100,000 Japanese American civilians. As an active military leader, Roosevelt implemented a war strategy on two fronts that ended in the defeat of the Axis Powers and the development of the world's first nuclear bomb. Though he died months before the end of the war, his work on the post-war order shaped the new United Nations and the Bretton Woods international financial system. Roosevelt's health seriously declined during the war years, and he died three months into his fourth term. He was succeeded by Vice President Harry S. Truman. It was on Roosevelt's watch that the Democratic Party was returned to dominance, prosperity returned, and two great military enemies were destroyed.

Scholars, historians and the public typically rank Roosevelt alongside Abraham Lincoln and George Washington as one of the three greatest U.S. Presidents.

Election of 1932

With the economy ailing after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, many Democrats hoped that the 1932 elections would see the election of the first Democratic president since Woodrow Wilson, who left office in 1921. Roosevelt's 1930 re-election victory established him as the front-runner for the 1932 Democratic presidential nomination. With the help of allies such as Louis Howe, James Farley, and Edward M. House, Roosevelt rallied the progressive supporters of the Wilson while also appealing to many conservatives, establishing himself as the leading candidate in the South and West. The chief opposition to Roosevelt's candidacy came from Northeastern conservatives such as Al Smith, the 1928 Democratic presidential nominee. Smith hoped to deny Roosevelt the two-thirds support necessary to win the party's presidential nomination 1932 Democratic National Convention, and then emerge as the nominee after multiple rounds of balloting. Roosevelt entered the convention with a delegate lead due to his success in the 1932 Democratic primaries, but most delegates entered the convention unbound to any particular candidate. On the first presidential ballot of the convention, Roosevelt received the votes of more than half but less than two-thirds of the delegates, with Smith finishing in a distant second place. Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, who controlled the votes of Texas and California, threw his support behind Roosevelt after the third ballot, and Roosevelt clinched the nomination on the fourth ballot. With little input from Roosevelt, Garner won the vice presidential nomination. Roosevelt flew in from New York after learning that he had won the nomination, becoming the first major party presidential nominee to accept the nomination in person.[1]

In the general election, Roosevelt faced incumbent Republican President Herbert Hoover. Engaging in a cross-country campaign, Roosevelt promised to increase the federal government's role in the economy and to lower the tariff as part of a "New Deal." Hoover argued that the economic collapse had chiefly been the product of international disturbances, and he accused Roosevelt of promoting class conflict with his novel economic policies. Already unpopular due to the bad economy, Hoover's re-election hopes were further hampered by the Bonus March of 1932, which ended with the violent dispersal of thousands of protesting veterans. Roosevelt won 472 of the 531 electoral votes and 57.4% of the popular vote, making him the first Democratic presidential nominee since the Civil War to win a majority of the popular vote. In the concurrent Congressional elections, the Democrats took control of the Senate and built upon their majority in the House. The election marked the end of the Fourth Party System, during which time Republicans had generally dominated national elections.[2][3]

Personnel

Cabinet and administration

Roosevelt appointed powerful men to top positions but made certain he made all the major decisions, regardless of delays, inefficiency or resentment. Analyzing the president's administrative style, historian James MacGregor Burns concludes:

- The president stayed in charge of his administration...by drawing fully on his formal and informal powers as Chief Executive; by raising goals, creating momentum, inspiring a personal loyalty, getting the best out of people...by deliberately fostering among his aides a sense of competition and a clash of wills that led to disarray, heartbreak, and anger but also set off pulses of executive energy and sparks of creativity...by handing out one job to several men and several jobs to one man, thus strengthening his own position as a court of appeals, as a depository of information, and as a tool of co-ordination; by ignoring or bypassing collective decision-making agencies, such as the Cabinet...and always by persuading, flattering, juggling, improvising, reshuffling, harmonizing, conciliating, manipulating.[4]

For his first Secretary of State, Roosevelt selected Cordell Hull, a prominent Tennessean who had served in the House and Senate. Though Hull had not distinguished himself as a foreign policy expert, he was a long-time advocate of tariff reduction, was respected by his Senate colleagues, and did not hold ambitions for the presidency. Roosevelt's inaugural cabinet included several influential Republicans, including Secretary of the Treasury William H. Woodin, a well-connected industrialist who was personally close to Roosevelt, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, a progressive Republican who would play an important role in the New Deal, and Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, who had advised the Roosevelt campaign on farm policies. Roosevelt also appointed the first female Cabinet member, Secretary of Labor Frances C. Perkins. Farley became Postmaster General, while Howe became Roosevelt's personal secretary until his death in 1936. Ill health forced Woodin to resign in 1934, and he was succeeded by Henry Morgenthau Jr.[5]

As World War II approached, Roosevelt appointed new individuals to key positions. Frank Knox, the 1936 Republican vice presidential nominee, became Secretary of the Navy while former Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson became Secretary of War. Roosevelt began convening a "war cabinet" consisting of Hull, Stimson, Knox, Chief of Naval Operations Harold Rainsford Stark, and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall.[6] In 1942 Roosevelt set up a new military command structure with Admiral Ernest J. King (Stark's successor) as in complete control of the Navy and Marines. Marshall was in charge charge of the Army and nominally led the Air Force, which in practice was commanded by General Hap Arnold. Roosevelt formed a new body, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which made the final decisions on American military strategy.[7] The Joint Chiefs was a White House agency and was chaired by his old friend Admiral William D. Leahy. When dealing with Europe, the Joint Chiefs met with their British counterparts and formed the Combined Chiefs of Staff.[8][9] Unlike the political leaders of the other major powers, Roosevelt rarely overrode his military advisors.[10] His civilian appointees handled the draft and procurement of men and equipment, but no civilians – not even the secretaries of War or Navy, had a voice in strategy. Roosevelt avoided the State Department and conducted high level diplomacy through his aides, especially Harry Hopkins. Since Hopkins also controlled $50 billion in Lend-Lease funds given to the Allies, they paid attention to him.[11]

Roosevelt was the first president to have more than two vice presidents. Former Speaker of the House John Nance Garner of Texas, his first vice president, was added to the ticket as part of a deal at the 1932 Democratic National Convention which clinched the presidential nomination for Roosevelt.[12] Garner and Postmaster General James Farley tried to challenge Roosevelt for the presidential nomination at the 1940 Democratic National Convention, but Roosevelt won the nomination and chose Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace as his running mate.[12] Wallace was unpopular among many Democrats, who successfully replaced Wallace with Senator Harry S. Truman of Missouri at the 1944 Democratic National Convention. Truman would succeed Roosevelt as president after Roosevelt's death in April 1945.[13]

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court appointments

| Supreme Court Appointments by President Franklin D. Roosevelt | ||

|---|---|---|

| Position | Name | Term |

| Chief Justice | Harlan Fiske Stone | 1941–1946 |

| Associate Justice | Hugo Black | 1937–1971 |

| Stanley Forman Reed | 1938–1957 | |

| Felix Frankfurter | 1939–1962 | |

| William O. Douglas | 1939–1975 | |

| Frank Murphy | 1940–1949 | |

| James F. Byrnes | 1941–1942 | |

| Robert H. Jackson | 1941–1954 | |

| Wiley Blount Rutledge | 1943–1949 | |

Roosevelt appointed eight Supreme Court Justices, more than any other president except George Washington. Roosevelt's appointees upheld his policies,[14] but often disagreed in other areas, especially after Roosevelt's death.[15] William O. Douglas and Hugo Black served until the 1970s and joined or wrote many of the major decisions of the Warren Court, while Robert H. Jackson and Felix Frankfurter advocated judicial restraint and deference to elected officials.[16][17]

Other judicial nominees

Roosevelt made 51 appointments to the United States courts of appeals and 134 appointments to the United States district courts. He made more appointments to either court than any of his predecessors.

First and second terms (1933–41)

When Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, the economy had hit bottom. In the midst of the Great Depression, a quarter of the American workforce was unemployed, two million people were homeless, and industrial production had fallen by more than half since 1929.[18] By the evening of March 4, 32 of the 48 states – as well as the District of Columbia – had closed their banks.[19] The New York Federal Reserve Bank was unable to open on the 5th, as huge sums had been withdrawn by panicky customers in previous days.[20] Beginning with his inauguration address, Roosevelt began blaming the economic crisis on bankers and financiers, the quest for profit, and the self-interest basis of capitalism:

Primarily this is because rulers of the exchange of mankind's goods have failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and have abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men. True they have tried, but their efforts have been cast in the pattern of an outworn tradition. Faced by failure of credit they have proposed only the lending of more money. Stripped of the lure of profit by which to induce our people to follow their false leadership, they have resorted to exhortations, pleading tearfully for restored confidence... The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.[21]

Historians categorize Roosevelt's program to address the Great Depression into three categories: "relief, recovery and reform." Relief was urgently needed by tens of millions of unemployed. Recovery meant boosting the economy back to normal. Reform meant long-term fixes of what was wrong, especially with the financial and banking systems. Through Roosevelt's series of radio talks, known as fireside chats, he presented his proposals directly to the American public.[22]

First New Deal, 1933–34

Roosevelt's "First 100 Days" concentrated on the first part of his strategy: immediate relief. From March 9 to June 16, 1933, he sent Congress a record number of bills, all of which passed easily. To propose programs, Roosevelt relied on leading Senators such as George Norris, Robert F. Wagner, and Hugo Black, as well as his Brain Trust of academic advisers. Like Hoover, he saw the Depression caused in part by people no longer spending or investing because they were afraid. Congress also gave the Federal Trade Commission broad new regulatory powers. Roosevelt expanded a Hoover agency, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, making it a major source of financing for railroads and industry.[23]

Banking and financial reforms

Banking reform was perhaps the single most urgent task facing the newly-inaugurated Roosevelt administration. Thousands of banks had failed or were on the verge of failing, and panicked depositors sought to remove their savings from banks for fear that they would lose their deposits after a bank failure. In the months after Roosevelt's election, several governors declared bank holidays, temporarily closing banks so that their deposits could not be withdrawn. On March 5, Roosevelt declared a federal bank holiday, closing every bank in the nation. Though some questioned Roosevelt's constitutional authority to declare a bank holiday (Roosevelt relied on the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 as justification), his action received little immediate political resistance in light of the severity of the crisis.[24]

He called for a special session of Congress to start March 9, at which Congress quickly passed the Emergency Banking Act. The banking crisis was resolved, thanks to $1.2 billion in loans from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to over 6000 banks. Depositors in permanently closed banks were eventually repaid 85 cents on the dollar for their deposits. Depositors in open banks received insurance coverage from the new Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Roosevelt himself was dubious about insuring bank deposits, saying, "We do not wish to make the United States Government liable for the mistakes and errors of individual banks, and put a premium on unsound banking in the future." But public support was overwhelmingly in favor, and the number of bank failures dropped to near zero.[25]

To give Americans confidence in the financial system, Congress enacted the Glass–Steagall Act, which curbed speculation by limiting the investments commercial banks could make and ending affiliations between commercial banks and securities firms. Hoarding of gold was made illegal, in preparation for Roosevelt's effort to pump up inflation rates. The president was given more control over the Federal Reserve System. Home mortgage financing was facilitated by the new Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), which created a market for mortgages and reduced foreclosures.

In 1934, Congress established the independent Securities and Exchange Commission to end irresponsible market manipulations, and dissemination of false information about securities.[26] The SEC remains in the 21st century one of the most powerful of all government agencies. Its predecessor had been ineffective in 1933-34 as part of another agency and the financial market was moribund. Roosevelt named Joseph P. Kennedy, a famously successful speculator himself, to head the SEC and clean up Wall Street. The New Deal attracted many of the nation's most talented young lawyers. Kennedy appointed a hard-driving team with a mission for reform that included William O. Douglas, and Abe Fortas, both of whom were later named to the U.S. Supreme Court.[27] The SEC had four missions. First and most important was to restore investor confidence in the securities market, which is practically collapsed because of doubts about its internal integrity, and the external threats supposedly posed by anti-business elements in the Roosevelt administration. Second, In terms of integrity, the SEC had to get rid of the penny ante swindles based on false information, fraudulent devices, and unsound get-rich-quick schemes. That unsavory had to be shut down. Thirdly, and much more important than the frauds, the SEC had to end the million-dollar insider maneuvers in major corporations, whereby insiders with access to much better information about the condition of the company knew when to buy or sell their own securities. A crackdown on insider trading was essential. Finally, the SEC had to set up a complex system of registration for all securities sold in America, with a clear-cut set of rules and guidelines that everyone had to follow. Drafting precise rules was the main challenge faced by the bright young lawyers. The SEC succeeded in its four missions, as Kennedy reassured the American business community that they would no longer be deceived and tricked and taken advantage of by Wall Street. He became a cheerleader for ordinary investors to return to the market and enable the economy to grow again.[28]

|

Nothing to Fear

Sample of the Inaugural speech from FDR |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Relief for unemployed

Relief for the unemployed was a major priority for the New Deal, and Roosevelt copied the programs he had initiated as governor of New York.[29][30] Some of the New Deal programs, such as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), were continuations of Hoover programs. FERA was designed to channel money to states and localities that organize their own work relief programs. Closely related to FERA was the Civil Works Administration (CWA), which operated only in the winter of 1933-34. In 1935, Roosevelt closed FERA in favor of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the Public Works Administration (PWA).[31][32]

FERA, the largest program from 1933 to 1935, involved giving money to localities to operate work relief projects to employ those on direct relief. CWA was similar, but did not require workers to be on relief in order to receive a government sponsored job. In less than four months, the CWA hired four million people, and during its five months of operation, the CWA built and repaired 200 swimming pools, 3,700 playgrounds, 40,000 schools, 250,000 miles (400,000 km) of road, and 12 million feet of sewer pipe.[33]

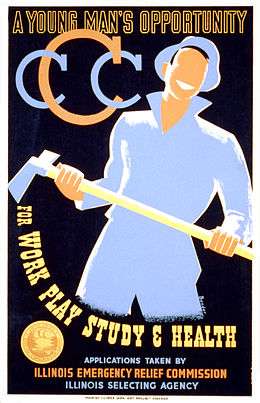

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC)

The most popular of all New Deal agencies – and Roosevelt's favorite– was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).[34] The CCC hired 250,000 unemployed young men to work for six months on rural projects. It was directed by Robert Fechner, a former union executive who promised labor unions that the enrolees would not be trained in skills that would compete with unemployed union members. Instead, they did unskilled construction labor, building roads and recreational facilities in state and national parks. CCC made a positive long-term impact on the environment. Each CCC camp was administered by a US Army reserve officer. Food, supplies, and medical services were purchased locally. The young men were paid a dollar a day, most of which went to their parents. Blacks were enrolled in their own camps, and the CCC operated an entirely separate division for Indians.[35]

Agriculture

Roosevelt made agricultural needs a high priority,[36] and he kept in close touch with national and state leaders of farm organizations. Leadership of the farm programs of the New Deal lay with Henry Wallace as the dynamic, intellectual reformer as Secretary of Agriculture.[37][38] Farming was not prosperous in the 1920s; many had added debt to buy more land and foreclosures were common. The fall in prices received for crops and animals fell sharply after 1929.[39] In the 1930s, Midwestern farmers would additionally have to contend with a series of severe dust storms known as the Dust Bowl, provoking migration from the affected regions.[40]

Roosevelt's "First Hundred Days" produced the Farm Security Act to raise farm incomes by raising the prices farmers received, which was achieved by reducing total farm output. In May 1933 the Agricultural Adjustment Act created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). The act reflected the demands of leaders of major farm organizations, especially the Farm Bureau, and reflected debates among Roosevelt's farm advisers such as Wallace, M.L. Wilson, Rexford Tugwell, and George Peek.[41] The main agricultural New Deal program, until the Supreme Court struck it down in 1934, was the AAA. The AAA tried to force higher prices for commodities by paying farmers to take land out of crops and to cut herds.[42]

The aim of the AAA was to raise prices for commodities through artificial scarcity. The AAA used a system of "domestic allotments", setting total output of corn, cotton, dairy products, hogs, rice, tobacco, and wheat. The farmers themselves had a voice in the process of using government to benefit their incomes. The AAA paid land owners subsidies for leaving some of their land idle with funds provided by a new tax on food processing. The goal was to force up farm prices to the point of "parity", an index based on 1910–1914 prices. To meet 1933 goals, 10 million acres (40,000 km2) of growing cotton was plowed up, bountiful crops were left to rot, and six million piglets were killed and discarded.[43] The idea was the less produced, the higher the wholesale price and the higher income to the farmer. Farm incomes increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal, as prices for commodities rose. Food prices remained well below 1929 levels.[44][45]

The AAA established a long-lasting federal role in the planning of the entire agricultural sector of the economy, and was the first program on such a scale on behalf of the troubled agricultural economy. The original AAA did not provide for any sharecroppers or tenants or farm laborers who might become unemployed, but there were other New Deal programs especially for them, such as the Farm Security Administration.[46]

In 1936, the Supreme Court declared the AAA to be unconstitutional for technical reasons; it was replaced by a similar program that did win Court approval. Instead of paying farmers for letting fields lie barren, the new program instead subsidized them for planting soil enriching crops such as alfalfa that would not be sold on the market. Federal regulation of agricultural production has been modified many times since then, but together with large subsidies the basic philosophy of subsidizing farmers remains in effect.[47]

New Dealers exaggerated the importance of farming to the economy, and believed that recovery in agriculture was needed to lead the whole nation back to prosperity.[48] They initiated numerous programs for farmers, but year after year the farm population shrank, with the exodus speeding up after 1940.[49] The sector reached its low point in terms of income in 1932, but even then millions of unemployed people were returning to the family farm having given up hope for a job in the cities. The main New Deal strategy was to reduce the supply of commodities, thereby raising the prices a little to the consumer, and a great deal to the farmer. Marginal farmers produce too little to be helped by the strategy; specialized relief programs were developed for them. Prosperity largely returned to the farm by 1936.[50]

Rural relief

Many rural people lived in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the Resettlement Administration (RA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and other rural welfare projects including school lunches, the construction of new schools and roads, reforestation, and the purchase of marginal lands to enlarge national forests. In 1933, the administration launched the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a project involving dam construction planning on an unprecedented scale in order to curb flooding, generate electricity, and modernize the very poor farms in the Tennessee Valley region of the Southern United States.[51][52]

Agencies such as the Resettlement Administration and the Farm Security Administration represented the first national program to help migrant and marginal farmer,. Their plight gained national attention through the 1939 novel and film The Grapes of Wrath. New Deal leaders resisted demands of the poor for loans to buy farms, as many leaders thought that there were already too many farmers.[53] However, the Roosevelt administration made a major effort to upgrade the health facilities available to a sickly population.[54]

Agriculture was very prosperous during World War II, even as rationing and price controls limited the availability of meat and other foods in order to guarantee its availability to the American And Allied armed forces. During World War II, farmers were not drafted, but surplus labor, especially in the southern cotton fields, voluntarily relocated to war jobs in the cities.[55][56]

NRA

Reform of the economic waste was the goal of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933, which established both the PWA and the National Recovery Administration (NRA).[57] The NRA tried to end cutthroat competition by forcing industries to come up with codes that established the rules of operation for all firms within specific industries, such as minimum prices, minimum wages, agreements not to compete, and production restrictions. Industry leaders negotiated the codes which were approved by NIRA officials. Industry needed to raise wages as a condition for approval. Other provisions encouraged unions and suspended anti-trust laws. The NRA targeted ten essential industries deemed crucial to an economic recovery, starting with textile industry and next turning to coal, oil, steel, automobiles, and lumber. Though unwilling to dictate the codes to industries, the administration pressured companies to agree to the codes and urged consumers to purchase products from companies in compliance with the codes.[58] The Supreme Court found NIRA to be unconstitutional by unanimous decision in May 1935.[59]

Cutting the regular budget

Roosevelt argued that the emergency spending programs for relief were temporary. He kept his campaign promise to cut the regular federal budget — including a reduction in military spending from $752 million in 1932 to $531 million in 1934. He made a 40% cut in spending on veterans' benefits by removing 500,000 veterans and widows from the pension rolls and reducing benefits for the remainder, as well as cutting the salaries of federal employees and reducing spending on research and education. But, the veterans were well organized and strongly protested; most benefits were restored or increased by 1934, but FDR vetoed their efforts to get a cash bonus.[60] The benefit cuts also did not last. In June 1933, Roosevelt restored $50 million in pension payments, and Congress added another $46 million more.[61] Veterans groups such as the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars won their campaign to transform their benefits from payments due in 1945 to immediate cash when Congress overrode the President's veto and passed the Bonus Act in January 1936.[62][63] It pumped sums equal to 2% of the GDP into the consumer economy and had a major stimulus effect.[64]

Ending prohibition

Roosevelt had generally avoided the Prohibition issue, but when his party and the general public swung against Prohibition in 1932, he campaigned for repeal. During the Hundred Days he signed the Cullen–Harrison Act redefining weak beer (3.2% alcohol) as the maximum allowed. The 21st Amendment was ratified later that year; he was not involved in the amendment but was given much of the credit. The repeal of prohibition brought in new tax revenues to federal, state and local governments and helped Roosevelt keep a campaign promise that attracted widespread popular support. It also weakened the big-city criminal gangs that had profited heavily from illegal liquor sales.[65]

Education

The New Deal approach to education was a radical departure from previous practices. It was specifically designed for the poor and staffed largely by women on relief. It was not based on professionalism, nor was it designed by experts. Instead it was premised on the anti-elitist notion that a good teacher does not need paper credentials, that learning does not need a formal classroom and that the highest priority should go to the bottom tier of society. Leaders in the public schools were shocked: they were shut out as consultants and as recipients of New Deal funding. They desperately needed cash to cover the local and state revenues that it disappeared during the depression, they were well organized, and made repeated concerted efforts in 1934, 1937, and 1939, all to no avail. The federal government had a highly professional Office of Education; Roosevelt cut its budget and staff, and refused to consult with its leader John Ward Studebaker.[66] The CCC programs were deliberately designed not teach skills that would put them in competition with unemployed union members. The CCC did have its own classes. They were voluntary, took place after work, and focused on teaching basic literacy to young men who had quit school before high school.[67]

The relief programs did offer indirect help. The CWA and FERA focused on hiring unemployed people on relief, and putting them to work on public buildings, including public schools. It built or upgraded 40,000 schools, plus thousands of playgrounds and athletic fields. It gave jobs to 50,000 teachers to keep rural schools open and to teach adult education classes in the cities. It gave a temporary jobs to unemployed teachers in cities like Boston.[68][69] Although the New Deal refused to give money to impoverished school districts, it did give money to impoverished high school and college students. The CWA used "work study" programs to fund students, both male and female.[70]

The National Youth Administration (NYA), a semi-autonomous branch of the WPA under Aubrey Williams developed apprenticeship programs and residential camps specializing in teaching vocational skills. It was one of the first agencies to set up a “Division of Negro Affairs" and make an explicit effort to enroll black students. Williams believed that the traditional high school curricula had failed to meet the needs of the poorest youth. In opposition, the well-established National Education Association (NEA) saw NYA as a dangerous challenge to local control of education NYA expanded Work-study money to reach up to 500,000 students per month in high schools, colleges, and graduate schools. The average pay was $15 a month.[71][72] However, in line with the anti-elitist policy, the NYA set up its own high schools, entirely separate from the public school system or academic schools of education.[73][74] Despite appeals from Ickes and Eleanor Roosevelt, Howard University–the federally operated school for blacks—saw its budget cut below Hoover administration levels.[75]

Second New Deal, 1935–36

Social Security

After the 1934 Congressional elections, which gave Roosevelt large majorities in both houses, his administration drafted a fresh surge of New Deal legislation. The most important program of 1935, and perhaps the New Deal as a whole, was the Social Security Act, drafted by Frances Perkins. It established a permanent system of universal retirement pensions (Social Security), unemployment insurance, and welfare benefits for the handicapped and needy children in families without a father present.[76] The United States had been the only modern industrial country where people faced the Depression without any national system of social security, though a handful of states had old age insurance laws.[77] Roosevelt insisted that it should be funded by payroll taxes rather than from the general fund; he said, "We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program."[78] Compared with the social security systems in western European countries, the Social Security Act of 1935 was rather conservative. But for the first time the federal government took responsibility for the economic security of the aged, the temporarily unemployed, dependent children and the handicapped.[79]

WPA

Roosevelt expanded unemployment relief through the establishment of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), headed by close friend Harry Hopkins, who had formerly led FERA and the CWA. The WPA focused on infrastructure projects such as Though nominally charged only with undertaking construction projects that cost over $25,000, the WPA provided grants for other programs, such as the Federal Writers' Project.[80] The WPA also financed a variety of projects such as hospitals, schools, and roads, and employed more than 8.5 million workers who built 650,000 miles of highways and roads, 125,000 public buildings, as well as bridges, reservoirs, irrigation systems, and other projects.[81] One semi-autonomous unit was the National Youth Administration (NYA). The NYA worked closely with high schools and colleges to set up work-study programs, and even operated its own coeducational high schools, reaching 400,000 students.[82][83]

National Labor Relations Act

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act, guaranteed workers the rights to collective bargaining through unions of their own choice. The act also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to facilitate wage agreements and to suppress the repeated labor disturbances. The Wagner Act did not compel employers to reach agreement with their employees, but it opened possibilities for American labor.[84] The result was a tremendous growth of membership in the labor unions, especially in the mass-production sector.[85] When the Flint sit-down strike threatened the production of General Motors, Roosevelt broke with the precedent set by many former presidents and refused to intervene; the strike ultimately led to the unionization of both General Motors and its rivals in the American automobile industry.[86]

Liberty League in opposition

While the First New Deal of 1933 had broad support from most sectors, the Second New Deal challenged the business community. Conservative Democrats, led by Al Smith, fought back with the American Liberty League, savagely attacking Roosevelt and equating him with Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.[87] But Smith overplayed his hand, and his boisterous rhetoric let Roosevelt isolate his opponents and identify them with the wealthy vested interests that opposed the New Deal, strengthening Roosevelt for the 1936 landslide. By contrast, the labor unions, energized by the Wagner Act, signed up millions of new members and became a major backer of Roosevelt's reelections in 1936, 1940 and 1944.[88]

Second term legislation

In contrast to his first term, little major legislation was passed during Roosevelt's second term, in large part due to opposition from the conservative coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats. There was the Housing Act of 1937, a second Agricultural Adjustment Act, and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which created the minimum wage and was the last major domestic reform measure of the New Deal.[89] When the economy began to deteriorate again in late 1937, Roosevelt asked Congress for $5 billion in WPA relief and public works funding. This managed to eventually create as many as 3.3 million WPA jobs by 1938. Projects accomplished under the WPA ranged from new federal courthouses and post offices, to facilities and infrastructure for national parks, bridges and other infrastructure across the country, and architectural surveys and archeological excavations — investments to construct facilities and preserve important resources. Beyond this, however, Roosevelt recommended to a special congressional session only a permanent national farm act, administrative reorganization and regional planning measures, which were leftovers from a regular session. According to Burns, this attempt illustrated Roosevelt's inability to decide on a basic economic program.[90]

Roosevelt signed the Reorganization Act of 1939, which granted him the power to reorganize the executive department and authorized the president to increase the size of his staff. In his subsequent reorganization, Roosevelt established the Executive Office of the President, which increased the president's control over the executive branch.[91] Roosevelt also combined several government agencies into the Federal Works Agency, the Federal Security Agency, and the Federal Loan Agency.

Supreme Court fight

Roosevelt's New Deal policies often ran into opposition from the Supreme Court, especially from the conservative Four Horsemen. The more conservative members of the court upheld the principles of the Lochner era, which saw numerous economic regulations struck down on the basis of freedom of contract.[92] In particular in 1935, the Court unanimously ruled that the National Industrial Recovery Act was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the president and relied on an overly-broad interpretation of the Commerce Clause. Roosevelt attempted to increase the size of the Court so that he could appoint more favorable justices, but Roosevelt's plan was defeated by his own party.[93] However, starting with the 1937 West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, in a phenomenon known as "the switch in time that saved nine," the court began to take a more favorable view of economic regulations. That same year, Roosevelt appointed a Supreme Court Justice for the first time, and by 1941, eight of the nine Justices were Roosevelt appointees. Of the justices on the court when Roosevelt took office, only Owen Roberts and Harlan Fiske Stone (who Roosevelt elevated to Chief Justice) outlasted Roosevelt.[94]

Economic policies

Government spending increased from 8.0% of gross national product (GNP) under Hoover in 1932 to 10.2% of the GNP in 1936. The national debt as a percentage of the GNP had more than doubled under Hoover from 16% to 40% of the GNP in early 1933. It held steady at close to 40% as late as fall 1941, then grew rapidly during the war.[95]

Deficit spending had been recommended by some economists, most notably by John Maynard Keynes of Britain, but was opposed by Roosevelt and Treasury Secretary Morgenthau.[96] The GNP was 34% higher in 1936 than in 1932 and 58% higher in 1940 on the eve of war. That is, the economy grew 58% from 1932 to 1940 in 8 years of peacetime, and then grew 56% from 1940 to 1945 in 5 years of wartime.[95]

Unemployment fell dramatically in Roosevelt's first term, from 25% when he took office to 14% in 1937. However, it increased to 19% in 1938 ("a depression within a depression") and fell to 17% in 1939, and then dropped again to 14.6% in 1940 until it reached 2% in 1945 during World War II. Many of the unemployed actually had jobs with the WPA or other relief agencies, but were still counted as "unemployed." [97] Total employment during Roosevelt's term expanded by 18.31 million jobs, with an average annual increase in jobs during his administration of 5.3%.[98][99]

Roosevelt did not raise income taxes before World War II began; however payroll taxes were introduced to fund the new Social Security program in 1937. He also convinced Congress to spend more on many various programs never before seen in American history. Under the revenue pressures brought on by the depression, most states added or increased taxes, including sales as well as income taxes. Roosevelt's proposal for new taxes on corporate savings were highly controversial in 1936–37, and were rejected by Congress. During the war he pushed for even higher income tax rates for individuals (reaching a marginal tax rate of 91%) and corporations and a cap on high salaries for executives. He also issued Executive Order 9250 in October 1942, later to be rescinded by Congress, which raised the marginal tax rate for salaries exceeding $25,000 (after tax) to 100%, thereby limiting salaries to $25,000 (about $366,000 today).[100][101][102] To fund the war, Congress not only broadened the base so that almost every employee paid federal income taxes, but also introduced withholding taxes in 1943.

Conservation and the environment

Roosevelt had a lifelong interest in the environment and conservation starting with his youthful interest in forestry on his family estate. As governor and president, he launched numerous projects for conservation, in the name of protecting the environment, and providing beauty and jobs for the people. He was strengthened in his resolve by the model of his cousin Theodore Roosevelt. Although FDR was never an outdoorsman or sportsman on TR's scale, his growth of the national systems were comparable. FDR created 140 national wildlife refuges (especially for birds) and established 29 national forests and 29 national parks and monuments.[103][104] He thereby achieved the vision he had set out in 1931:

- Heretofore our conservation policy has been merely to preserve as much as possible of the existing forests. Our new policy goes a step further. It will not only preserve the existing forests, but create new ones.[105]

As president he was active in expanding, funding, and promoting the National Park and National Forest systems. He used relief agencies to upgrade the facilities. Their popularity soared, from three million visitors a year at the start of the decade, to 15.5 million in 1939.[106] His favorite agency was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which expended most of its effort on environmental projects. The CCC in a dozen years enrolled 3.4 million young men; they built 13,000 miles of trails, planted two billion trees and upgraded 125,000 miles of dirt roads. Every state had its own state parks, and Roosevelt made sure that WPA and CCC projects were set up to upgrade them as well as the national systems.[107][108] Roosevelt heavily funded the system of dams to provide flood control, electricity, and modernization of rural communities through the Tennessee Valley Authority, as well as less famous projects transforming western rivers. He was a great dam builder, although 21st century critics would see this as the antithesis of conservation.[109]

Foreign policy

The main foreign policy initiative of Roosevelt's first term was what he called the Good Neighbor Policy, which continued the move begun by Coolidge and Hoover toward a more non-interventionist policy in Latin America. Since the promulgation of the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, this area had been seen as an American sphere of influence. American forces were withdrawn from Haiti, and new treaties with Cuba and Panama ended their status as protectorates. In December 1933, Roosevelt signed the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, renouncing the right to intervene unilaterally in the affairs of Latin American countries.[110][111]

The American rejection of the League of Nations treaty in 1919 marked a refusal to use world organizations in American foreign policy. Learning from Wilson's mistakes, Roosevelt and Secretary of State Hull acted with great care not to provoke isolationist sentiment.[112] Roosevelt's "bombshell" message to the London Economic Conference in 1933 effectively ended any major efforts by the world powers to collaborate on ending the worldwide depression, and allowed Roosevelt a free hand in economic policy.[113] Though Roosevelt favored low tariffs, he was unwilling to accept a fixed exchange-rate system or to reduce European debts incurred during World War I.[114] The isolationist movement was bolstered in the early to mid-1930s by U.S. Senator Gerald Nye and others who succeeded in their effort to stop the "merchants of death" in the U.S. from selling arms abroad.[115] Isolationists passed the Neutrality Acts; the president asked for, but was refused, a provision to give him the discretion to allow the sale of arms to victims of aggression.[116] Though he privately opposed them, Roosevelt signed the Neutrality Acts in order to preserve his political capital for his domestic agenda.[117]

In 1931, the Empire of Japan invaded the Chinese region of Manchuria, establishing the puppet state of Manchukuo. The United States and the League of Nations condemned the invasion, but none of the great powers made any move to evict Japan from the region, and the Japanese appeared poised to further expand their empire. Two years later, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came into power in Germany. At first, many in the United States thought of Hitler as a something of a comic figure, but Hitler quickly consolidated his power in Germany and attacked the post-war order established by the Treaty of Versailles. In 1936, Germany and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact, though they never coordinated their strategies.[118] Roosevelt saw the threat that both of these rising powers posed, but focused on reviving the U.S. economy during the early part of his presidency. Partly out of a desire to balance Japan and Germany, Roosevelt normalized relations with the Soviet Union in 1933; the U.S. had not had relations with the country since the October Revolution.[119]

Foreign affairs became a more prominent issue in the Roosevelt administration as the 1930s progressed.[120] Italy, under a fascist regime led by Benito Mussolini, invaded Ethiopia, earning international condemnation. The Italians also joined Nazi Germany in supporting General Francisco Franco and the Nationalist cause in the Spanish Civil War.[121] When Japan invaded China in 1937, public opinion strongly favored China, and Roosevelt found various ways to assist that nation.[122] On October 5, 1937, he gained national and international attention with his Quarantine Speech calling for an international "quarantine" against the "epidemic of world lawlessness" by aggressive nations. He named no countries but readers saw the reference to Japan, Italy, and Germany.[123] Meanwhile, Roosevelt secretly stepped up a program to build long-range submarines that could blockade Japan.[124]

War clouds

In 1938, Germany demanded the annexation of parts of Czechoslovakia, resulting in the Munich Agreement among the great powers of Europe. At the time of the Munich Agreement, Roosevelt said the country would not join a "stop-Hitler bloc" under any circumstances. He made it quite clear that, in the event of German aggression against Czechoslovakia, the U.S. would remain neutral.[125][126] Roosevelt said in 1939 that France and Britain were America's "first line of defense" and needed American aid, but because of widespread isolationist sentiment, he reiterated the US itself would not go to war.[127] In the spring of 1939, Roosevelt allowed the French to place huge orders with the American aircraft industry on a cash-and-carry basis, as allowed by law. Most of the aircraft ordered had not arrived in France by the time of its collapse in May 1940, so Roosevelt arranged in June 1940 for French orders to be sold to the British.[128]

In August 1939, Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein sent the Einstein–Szilárd letter to Roosevelt, warning of the possibility of a German project to develop nuclear weapons. Szilard realized that the recently discovered process of nuclear fission could be used to create a nuclear chain reaction that could be used as a weapon of mass destruction. Roosevelt established the Advisory Committee on Uranium, which eventually evolved into the Manhattan Project, which created the first atomic bomb in 1945.[129]

Start of World War II

World War II began in September 1939 with Germany's invasion of Poland, as France and Britain declared war in response. The United States would remain officially neutral until December 1941, but Roosevelt sought ways to assist Britain and France militarily.[130] He began a regular secret correspondence with the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill in September 1939 — the first of 1,700 letters and telegrams between them – discussing ways of supporting Britain.[131] Roosevelt forged a close personal relationship with Churchill, who became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in May 1940. Germany invaded Denmark and Norway in April 1940 and invaded the Low Countries and France in May. As France's situation grew increasingly desperate, Churchill and French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud appealed to Roosevelt for an American entry into the war, but Roosevelt was unwilling to challenge the isolationist sentiment in the United States.[132] France surrendered on June 22, resulting in the division of France into a German-controlled zone and a partially-occupied area known Vichy France. Roosevelt tried to work with Vichy France in 1940-42 to keep it neutral, with scant success.[133]

With the fall of France, Britain and its dominions became the lone major force at war with Germany in 1940-41. Roosevelt, who was determined that Britain not be defeated, took advantage of the rapid shifts of public opinion; the fall of Paris shocked American opinion, leading to a decline in isolationist sentiment. A consensus was clear that military spending had to be dramatically expanded, though there was no consensus as to how much the US should risk war in helping Britain.[134] In July 1940, FDR appointed two interventionist Republican leaders, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretaries of War and the Navy, respectively. Both parties gave support to his plans for a rapid build-up the American military, but the isolationists warned that Roosevelt would get the nation into an unnecessary war with Germany.[135] Congress authorized the nation's first peacetime draft.[136]

Roosevelt used his personal charisma to build support for intervention. America should be the "Arsenal of Democracy", he told his fireside audience.[137] On September 2, 1940, Roosevelt openly defied the Neutrality Acts by passing the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, which, in exchange for military base rights in the British Caribbean Islands, gave 50 WWI American destroyers to Britain. The U.S. also received free base rights in Bermuda and Newfoundland, allowing British forces to be moved to the sharper end of the war; the idea of an exchange of warships for bases such as these originated in the cabinet.[138] Hitler and Mussolini responded to the deal by joining with Japan in the Tripartite Pact, and the three countries became known as the Axis powers.[139] After the start of the war in Europe, Japan grew increasingly assertive in the Pacific, demanding that the French and British colonies close their borders with China.[140]

The agreement with Britain was a precursor of the March 1941 Lend-Lease agreement, which began to direct massive military and economic aid to Britain, the Republic of China, and later the Soviet Union. For foreign policy advice, Roosevelt turned to Harry Hopkins, who became his chief wartime advisor. They sought innovative ways short of going to war to help Britain, whose financial resources were exhausted by the end of 1940.[141] With the waning of isolationist sentiment, Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941, allowing the U.S. to give Britain, China, and later the Soviet Union military supplies. Congress voted to commit to spend $50 billion on military supplies from 1941 to 1945. In sharp contrast to the loans of World War I, there would be no repayment after the war. Until late in 1941, Roosevelt refused Churchill's urgent requests for armed escort of ships bound for Britain, insisting on a more passive patrolling function in the western Atlantic.[142]

As Roosevelt took a firmer stance against the Axis Powers, American isolationists (including Charles Lindbergh and America First) vehemently attacked the President as an irresponsible warmonger.[143] Roosevelt initiated FBI and Internal Revenue Service investigations of his loudest critics, though no legal actions resulted.[144] Unfazed by these criticisms and confident in the wisdom of his foreign policy initiatives, FDR continued his twin policies of preparedness and aid to the Allied coalition. On December 29, 1940, he delivered his Arsenal of Democracy fireside chat, in which he made the case for involvement in the war directly to the American people. A week later he delivered his famous Four Freedoms speech laying out the case for an American defense of basic rights throughout the world.

New Deal political coalition

The New Deal coalition was the alignment of interest groups and voting blocs that supported the New Deal and voted for Democratic presidential candidates from 1932 until the mid 1960s. It made the Democratic Party the majority party during that period, losing only to Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956. The American political system that incorporated the coalition and its opposition is characterized by scholars as the Fifth Party System. Roosevelt forged a coalition that the Democratic state party organizations, city machines, labor unions, blue collar workers, minorities (racial, ethnic and religious), farmers, white Southerners, people on relief, long-time middle class and business class Democrats, and intellectuals.[145][146]

White ethnics

The impact of the Prohibition issue, Great Depression, New Deal and World War II on white ethnic groups (mostly Catholics and Jews) was enormous. In the 1920s they were poor, were ignored politically marginal, and suffered a sharp inferiority complex. Political participation was low among the "new" immigrants who arrived after 1890; The established machines did not need their votes. The Depression tis these new immigrants hard, for they had low skill levels and were concentrated in heavy industry. They needed some sort of new deal and its relief programs came through for them. In terms of politics, the Catholic ethnics were one of the largest and most critical voting blocs in the New Deal coalition. Roosevelt scored large majorities among the main Catholics groups up to 1940. In particular he held the Irish, who included most of the ethnic political leaders, despite Al Smith's repudiation of the New Deal. The Catholic ethnics were beholden to welfare programs (especially the WPA, PWA and CCC), to city machines, and to labor unions. Nevertheless, there was change over time. The war brought prosperity of the sort never dreamed of, plus an opportunity to demonstrate patriotism in action, in war factories and battlefields.[147]

Isolationist sentiment was strong among the Irish, Germans and Italians in 1940. FDR's losses were heavy among the Germans, especially in rural Midwest, but Roosevelt scored large enough majorities in the 100 largest cities to overcome this deficit in rural and small-town America.[148][149][150][151]

African American politics

Roosevelt, aided especially by his wife, Eleanor and his Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, made systematic efforts to transform the African-American political community from a Republican to the Democratic allegiance. They largely succeeded, and blacks voted increasingly Democratic in the North, as large-scale immigration brought hundreds of thousands of new voters into the northern cities every year. During the war, Roosevelt issued an executive order that theoretically required corporations with government contracts to treat blacks and whites equally. Jobs in munitions factories were very high-paying.[152] The transition to the Democratic party played out in major cities in the North.[153]

However, Roosevelt needed the support of the powerful white Southern Democrats for his New Deal programs, and blacks were still disenfranchised in most of the South. He decided against pushing for federal anti-lynching legislation that would make lynching a federal crime. It could not pass over a Southern filibuster and the political fight would threaten his ability to pass his priority programs.[154] He did denounce lynchings as "a vile form of collective murder".[155]

Labor unions

Roosevelt at first had massive support from the rapidly growing labor unions, but they split into bitterly feuding AFL and CIO factions, the latter led by John L. Lewis. Roosevelt pronounced a "plague on both your houses," but labor's disunity weakened the party in the elections from 1938 through 1946.[156] Roosevelt won large majorities of the union votes, even in 1940 when John L. Lewis of the CIO and the UMW (the coal miners' union) took an isolationist position on Europe, as demanded by far-left union elements. Lewis denounced Roosevelt as a power-hungry war monger, and endorsed Republican Wendell Willkie.[157][158]

Third and fourth terms (1941–45)

|

State of the Union (Four Freedoms) (January 6, 1941)

Franklin Delano Roosevelt's January 6, 1941 State of the Union Address introducing the theme of the Four Freedoms (starting at 32:02) |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Roosevelt's third and fourth terms were dominated by World War II. Roosevelt considered his New Deal policies as central to his legacy, and in his 1944 State of the Union Address, he advocated that Americans should think of basic economic rights as a Second Bill of Rights. However, we conservative coalition blocked any efforts to put national planning into effect. It also closed down most of the relief programs, such as WPA, NYA and CCC.

Prelude to war

.png)

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt agreed to extend Lend-Lease to the Soviets. Thus, Roosevelt had committed the U.S. to the Allied side with a policy of "all aid short of war."[159] Execution of the aid fell victim to foot dragging in the administration so FDR appointed a special assistant, Wayne Coy, to expedite matters.[160] Later that year, a German submarine fired on the U.S. destroyer Greer, and Roosevelt declared that the U.S. Navy would assume an escort role for Allied convoys in the Atlantic as far east as Great Britain and would fire upon German ships or submarines (U-boats) of the Kriegsmarine if they entered the U.S. Navy zone. This "shoot on sight" policy effectively declared naval war on Germany and was favored by Americans by a margin of 2-to-1.[161]

Roosevelt and Churchill conducted a highly secret bilateral meeting in Argentia, Newfoundland, and on August 14, 1941, drafted the Atlantic Charter, conceptually outlining global wartime and postwar goals. All the Allies endorsed it. This was the first of several wartime conferences;[162] Churchill and Roosevelt met ten more times in person. In July 1941, Roosevelt had ordered Secretary of War Henry Stimson, to begin planning for total American military involvement. The resulting "Victory Program" provided the Army's estimates necessary for the total mobilization of manpower, industry, and logistics to defeat Germany and Japan. The program also planned to dramatically increase aid to the Allied nations and to have ten million men in arms, half of whom would be ready for deployment abroad in 1943. Roosevelt was firmly committed to the Allied cause, and these plans were formulated before the U.S. entered the war.[159]

Congress was debating a modification of the Neutrality Act in October 1941, when the USS Kearny, along with other ships, engaged a number of U-boats south of Iceland; the Kearny took fire and lost eleven crewmen. As a result, the amendment of the Neutrality Act to permit the arming of the merchant marine passed both houses, though by a slim margin.[163] However, neither the Kearny incident nor an attack on the USS Reuben James changed public opinion as much as Roosevelt hoped they might.[164]

In his role as the leader of the United States before and during World War II, Roosevelt tried to avoid repeating what he saw as Woodrow Wilson's mistakes in World War I.[165] He often made exactly the opposite decision. Wilson called for neutrality in thought and deed, while Roosevelt made it clear his administration strongly favored Britain and China. Unlike the loans in World War I, the United States made large-scale grants of military and economic aid to the Allies through Lend-Lease, with little expectation of repayment. Wilson did not greatly expand war production before the declaration of war; Roosevelt did. Wilson waited for the declaration to begin a draft; Roosevelt started one in 1940. Wilson never made the United States an official ally but Roosevelt did. Wilson never met with the top Allied leaders but Roosevelt did. Wilson proclaimed independent policy, as seen in the 14 Points, while Roosevelt sought a collaborative policy with the Allies. In 1917, United States declared war on Germany; in 1941, Roosevelt waited until the enemy attacked at Pearl Harbor. Wilson refused to collaborate with the Republicans; Roosevelt named leading Republicans to head the War Department and the Navy Department. Wilson let General George Pershing make the major military decisions; Roosevelt made the major decisions in his war including the "Europe first" strategy.[166] He rejected the idea of an armistice and demanded unconditional surrender. Roosevelt often mentioned his role as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the Wilson administration, but added that he had profited more from Wilson's errors than from his successes.[167][168][169][170]

Entrance into the war

When Japan occupied northern French Indochina in late 1940, FDR authorized increased aid to the Republic of China, a policy that won widespread popular support. In July 1941, after Japan occupied the remainder of Indochina, he cut off the sale of oil to Japan, which thus lost more than 95 percent of its oil supply. Roosevelt continued negotiations with the Japanese government, primarily through Secretary Hull. Japan Premier Fumimaro Konoye desired a summit conference with FDR which the US rejected. Konoye was replaced with Minister of War Hideki Tojo.[171] Meanwhile, Roosevelt started sending long-range B-17 bombers to the Philippines, which were under the control of the United States.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the Japanese struck the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor with a surprise attack, knocking out the main American battleship fleet and killing 2,403 American servicemen and civilians. FDR felt that an attack by the Japanese was probable – most likely in the Dutch East Indies, Thailand, or the Philippines.[172][6] The great majority of scholars have rejected the conspiracy thesis that Roosevelt, or any other high government officials, knew in advance about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese had kept their secrets closely guarded, and while senior American officials were aware that war was imminent, they did not expect an attack on Pearl Harbor.[173]

After Pearl Harbor, antiwar sentiment in the United States evaporated overnight. Roosevelt called for war in his famous "Infamy Speech" to Congress, in which he said: "Yesterday, December 7, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy — the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan." On December 8, Congress voted almost unanimously to declare war against Japan.[174] On December 11, 1941, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, which responded in kind.[175] Roosevelt portrayed the war as a crusade against the aggressive dictatorships that threatened peace and democracy throughout the world.[176] He and his military advisers implemented a war strategy with the objectives of halting the German advances in the Soviet Union and in North Africa; launching an invasion of western Europe with the aim of crushing Nazi Germany between two fronts; and saving China and defeating Japan. Public opinion, however, gave priority to the destruction of Japan, so American forces were sent chiefly to the Pacific in 1942. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan conquered the Philippines, as well as the British and Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia, capturing Singapore in February 1942. Furthermore, Japan cut off the overland supply route to China.[177]

Roosevelt met with Churchill in late December and planned a broad informal alliance among the U.S., Britain, China and the Soviet Union. This included Churchill's initial plan to invade North Africa (called Operation Gymnast) and the primary plan of the U.S. generals for a western Europe invasion, focused directly on Germany (Operation Sledgehammer). An agreement was also reached for a centralized command and offensive in the Pacific theater called ABDA (American, British, Dutch, Australian) to save China and defeat Japan. Nevertheless, the Atlantic First strategy was intact, to Churchill's great satisfaction.[178] On New Year's Day 1942, Churchill and FDR issued the "Declaration by United Nations", representing 26 countries in opposition to the Tripartite Pact of Germany, Italy and Japan.[179]

Homefront

The homefront was subject to dynamic social changes throughout the war, though domestic issues were no longer Roosevelt's most urgent policy concern. The military buildup spurred economic growth. Unemployment fell in half from 7.7 million in spring 1940 (when the first accurate statistics were compiled) to 3.4 million in fall 1941 and fell in half again to 1.5 million in fall 1942, out of a labor force of 54 million.[180] There was a growing labor shortage, accelerating the second wave of the Great Migration of African Americans, farmers and rural populations to manufacturing centers. African Americans from the South went to California and other West Coast states for new jobs in the defense industry. To pay for increased government spending, in 1941 FDR proposed that Congress enact an income tax rate of 99.5% on all income over $100,000; when the proposal failed, he issued an executive order imposing an income tax of 100% on income over $25,000, which Congress rescinded.[181]

In June 1941, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, forbidding discrimination on account of "race, creed, color, or national origin" in the hiring of workers in defense related industries.[182] This was a precursor to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act to come decades later.[183] Roosevelt established the Fair Employment Practices Committee to implement Executive Order 8802. This was the first national program directed against employment discrimination. African Americans who gained defense industry jobs in the 1940s shared in the higher wages; in the 1950s they had gained in relative economic position, about 14% higher than other blacks who were not in such industries. Their moves into manufacturing positions were critical to their success.[184]

In 1942, with the United States now in the conflict, war production increased dramatically, but fell short of the goals established by the President, due in part to manpower shortages.[185] The effort was also hindered by numerous strikes by union workers, especially in the coal mining and railroad industries, which lasted well into 1944.[186][187] The White House became the ultimate site for labor mediation, conciliation or arbitration.[188] One particular battle royal occurred, between Vice-President Wallace, who headed the Board of Economic Warfare, and Jesse Jones, in charge of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation; both agencies assumed responsibility for acquisition of rubber supplies and came to loggerheads over funding. FDR resolved the dispute by dissolving both agencies.[189]

In 1944, the President requested that Congress enact legislation which would tax all "unreasonable profits," both corporate and individual, and thereby support his declared need for over $10 billion in revenue for the war and other government measures. The Congress passed a revenue bill raising $2 billion, which FDR vetoed, though Congress in turn overrode him.[190]

Civil liberties and internment

Roosevelt had cultivated a friendly relationship with the domestic press throughout his presidency, and his good relations with the press helped ensure favorable coverage of his war-time policies without resorting to heavy-handed censorship. During World War I, the U.S. had passed acts such as the Sedition Act of 1918 to crack down on dissent, but Roosevelt largely avoided such harsh measures. He did order FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to increase its investigations of dissidents and signed the Smith Act, which made it a crime to advocate the overthrow of the federal government.[191]

When the war began, the danger of a Japanese attack on the coast led to growing pressure to move people of Japanese descent away from the coastal region. This pressure grew due to fears of terrorism, espionage, and/or sabotage; it was also related to anti-Japanese competition and discrimination. On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which relocated hundreds of thousands of the "Issei" (first generation of Japanese immigrants who did not have U.S. citizenship) and their children, "Nisei" (who had dual citizenship). They were forced to give up their properties and businesses, and transported to hastily built camps in interior, harsh locations. After both Nazi Germany and Italy declared war on the United States in December 1941, many German and Italian aliens who had not taken out American citizenship, and who were outspoken for Mussolini or Hitler were warned, or in some cases arrested and interned.[192]

Roosevelt's order to intern Japanese-Americans during the war remains a controversial decision, and is considered a blemish on his legacy.[193] The United States government has officially apologized for the actions, and in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which granted reparations of $20,000 to each surviving internee.

War strategy

Roosevelt, Churchill, General Secretary Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of China cooperated informally on a plan in which American and British troops concentrated in the West; Soviet troops fought on the Eastern front; and Chinese, British and American troops fought in Asia and the Pacific. The Allies formulated strategy in a series of high-profile conferences as well as through diplomatic and military channels. Roosevelt guaranteed that the U.S. would be the "Arsenal of Democracy" by shipping $50 billion of Lend-Lease supplies, primarily to Britain and to the USSR, China and other Allies. Roosevelt coined the term "Four Policemen" to refer this "Big Four" Allied powers of World War II, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and China.[194][195]

The Allies undertook the invasions of French Morocco and Algeria (Operation Torch) in November 1942. FDR very much desired the assault be initiated before election day, but did not order it. FDR and Churchill had another war conference in Casablanca in January 1943; Stalin declined an invitation. Roosevelt did meet with the Charles de Gaulle and Henri Giraud, the leaders of the Free French forces who opposed Germany and the Vichy government.[196] The Allies agreed strategically that the Mediterranean focus be continued, with the cross-channel invasion coming later, followed by concentration of efforts in the Pacific.[197] Hitler reinforced his military in North Africa, with the result that the Allied efforts there suffered a temporary setback; Allied attempts to counterbalance this were successful, but the setback delayed both the delivery of supplies to the USSR as well as the opening of a second war front.[198] Later, their assault pursued into Sicily (Operation Husky) followed in July 1943, and of Italy (Operation Avalanche) in September 1943. In 1943, it was apparent to FDR that Stalin, while bearing the brunt of Germany's offensive, had not had sufficient opportunity to participate in war conferences. The President made a concerted effort to arrange a one-on-one meeting with Stalin, in Fairbanks. However, when Stalin learned that Roosevelt and Churchill had postponed the cross-channel invasion a second time, he cancelled.[199] The strategic bombing campaign was escalated in 1944, pulverizing all major German cities and cutting off oil supplies. It was a 50–50 British-American operation. Roosevelt picked Dwight D. Eisenhower to head the Allied cross-channel invasion, Operation Overlord that began on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Some of the most costly battles of the war ensued after the invasion, and the Allies were blocked on the German border in the "Battle of the Bulge" in December 1944. When Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, Allied forces were closing in on Berlin.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, the Japanese advance reached its maximum extent by June 1942, when the U.S. Navy scored a decisive victory at the Battle of Midway. American and Australian forces then began a slow and costly progress called island hopping or leapfrogging through the Pacific Islands, with the objective of gaining bases from which strategic airpower could be brought to bear on Japan and from which Japan could ultimately be invaded. In contrast to Hitler, Roosevelt took no direct part in the tactical naval operations, though he approved strategic decisions.[200] FDR gave way in part to insistent demands from the public and Congress that more effort be devoted against Japan; he always insisted on Germany first. The strength of the Japanese navy was decimated in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and by April 1945 the Allies had re-captured much of their lost territory in the Pacific.[201]

Post-war planning

By late 1943, it was apparent that the Allies would ultimately defeat the enemy, so it became increasingly important to make high-level political decisions about the course of the war and the postwar future of Europe. Roosevelt met with Churchill and the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek at the Cairo Conference in November 1943, and then went to the Tehran Conference to confer with Churchill and Stalin. While Churchill warned of potential domination by a Stalin dictatorship over eastern Europe, Roosevelt responded with a statement summarizing his rationale for relations with Stalin: "I just have a hunch that Stalin is not that kind of a man. [...] I think that if I give him everything I possibly can and ask for nothing from him in return, noblesse oblige, he won't try to annex anything and will work with me for a world of democracy and peace."[202] At the Tehran Conference, Roosevelt and Churchill discussed plans for a postwar international organization. For his part, Stalin insisted on redrawing the frontiers of Poland. Stalin supported Roosevelt's plan for the United Nations and promised to enter the war against Japan 90 days after Germany was defeated. The 1944 Bretton Woods Conference laid the foundation for economic cooperation after the war.

By the beginning of 1945, with the Allied armies advancing into Germany and the Soviets in control of Poland, the postwar issues came into the open. In February, Roosevelt met with Churchill at Malta[203] and traveled to Yalta, in Crimea, to meet again with Stalin and Churchill. The Yalta Conference centered on the disposition of Europe after the war, and the allies agreed to set up separate occupation zones in Germany. The participants also agreed to the establishment of a United Nations Security Council, which would be led by the Big Four and provide for collective security.[204] While Roosevelt maintained his confidence that Stalin would keep his Yalta promises regarding free elections in eastern Europe, one month after Yalta ended, Roosevelt's Ambassador to the USSR Averell Harriman cabled Roosevelt that "we must come clearly to realize that the Soviet program is the establishment of totalitarianism, ending personal liberty and democracy as we know it."[205] Two days later, Roosevelt began to admit that his view of Stalin had been excessively optimistic and that "Averell is right."[205]