Presidential system

| |||||

| Systems of government | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

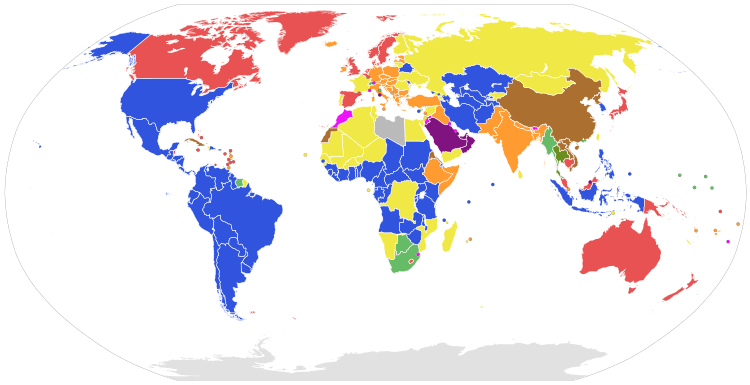

A presidential system is a democratic and republican system of government where a head of government leads an executive branch that is separate from the legislative branch. This head of government is in most cases also the head of state, which is called president.

In presidential countries, the executive is elected and is not responsible to the legislature, which cannot in normal circumstances dismiss it. Such dismissal is possible, however, in uncommon cases, often through impeachment.

The title "president" has persisted from a time when such person personally presided over the governing body, as with the President of the Continental Congress in the early United States, prior to the executive function being split into a separate branch of government.

A presidential system contrasts with a parliamentary system, where the head of government is elected to power through the legislative. There is an intermediary system called semi-presidentialism.

Countries that feature a presidential or semi-presidential system of government are not the exclusive users of the title of president. Heads of state of parliamentary republics, largely ceremonial in most cases, are called presidents. Dictators or leaders of one-party states, popularly elected or not, are also often called presidents.

Presidentialism is the dominant form of government in the continental Americas, with 20 of its 23 sovereign states being presidential republics. It is also prevalent in Central and Southern West Africa and in Central Asia.

Characteristics

In a full-fledged presidential system, a politician is chosen directly by the people or indirectly by the winning party to be the head of government. Except for Belarus and Kazakhstan, this head of government is also the head of state, and is therefore called president. The post of prime minister (also called premier) may also exist in a presidential system, but unlike in semi-presidential or parliamentary systems, the prime minister answers to the president and not to the legislature.

The following characteristics apply generally for the numerous presidential governments across the world:

- The executive can veto legislative acts and, in turn, a supermajority of lawmakers may override the veto. The veto is generally derived from the British tradition of royal assent in which an act of parliament can only be enacted with the assent of the monarch.

- The president has a fixed term of office. Elections are held at regular times and cannot be triggered by a vote of confidence or other parliamentary procedures, although in some countries there is an exception which provides for the removal of a president who is found to have broken a law.

- The executive branch is unipersonal. Members of the cabinet serve at the pleasure of the president and must carry out the policies of the executive and legislative branches. Cabinet ministers or executive departmental chiefs are not members of the legislature. However, presidential systems often need legislative approval of executive nominations to the cabinet, judiciary, and various lower governmental posts. A president generally can direct members of the cabinet, military, or any officer or employee of the executive branch, but cannot direct or dismiss judges.

- The president can often pardon or commute sentences of convicted criminals.

Subnational governments of the world

Subnational governments, usually states, may be structured as presidential systems. All of the state governments in the United States use the presidential system, even though this is not constitutionally required. On a local level, many cities use Council-manager government, which is equivalent to a parliamentary system, although the post of a city manager is normally a non-political position. Some countries without a presidential system at the national level use a form of this system at a subnational or local level. One example is Japan, where the national government uses the parliamentary system, but the prefectural and municipal governments have governors and mayors elected independently from local assemblies and councils.

Advantages

Supporters generally claim four basic advantages for presidential systems:

- Direct elections — in a presidential system, the president is often elected directly by the people. This makes the president's power more legitimate than that of a leader appointed indirectly. However, this is not a necessary feature of a presidential system. Some presidential states have an indirectly elected head of state.

- Separation of powers — a presidential system establishes the presidency and the legislature as two parallel structures. This allows each structure to monitor and check the other, preventing abuses of power.

- Speed and decisiveness — A president with strong powers can usually enact changes quickly. However, the separation of powers can also slow the system down.

- Stability — a president, by virtue of a fixed term, may provide more stability than a prime minister, who can be dismissed at any time.

Direct elections

In most presidential systems, the president is elected by popular vote, although some such as the United States use an electoral college (which is itself directly elected) or some other method.[1] By this method, the president receives a personal mandate to lead the country, whereas in a parliamentary system a candidate might only receive a personal mandate to represent a constituency. That means a president can only be elected independently of the legislative branch.

Separation of powers

A presidential system's separation of the executive from the legislature is sometimes held up as an advantage, in that each branch may scrutinize the actions of the other. In a parliamentary system, the executive is drawn from the legislature, making criticism of one by the other considerably less likely. A formal condemnation of the executive by the legislature is often considered a vote of no confidence. According to supporters of the presidential system, the lack of checks and balances means that misconduct by a prime minister may never be discovered. Writing about Watergate, Woodrow Wyatt, a former MP in the UK, said "don't think a Watergate couldn't happen here, you just wouldn't hear about it." (ibid)

Critics respond that if a presidential system's legislature is controlled by the president's party, the same situation exists. Proponents note that even in such a situation a legislator from the president's party is in a better position to criticize the president or his policies should he deem it necessary, since the immediate security of the president's position is less dependent on legislative support. In parliamentary systems, party discipline is much more strictly enforced. If a parliamentary backbencher publicly criticizes the executive or its policies to any significant extent then he/she faces a much higher prospect of losing his/her party's nomination, or even outright expulsion from the party. Even mild criticism from a backbencher could carry consequences serious enough (in particular, removal from consideration for a cabinet post) to effectively muzzle a legislator with any serious political ambitions.

Despite the existence of the no confidence vote, in practice it is extremely difficult to stop a prime minister or cabinet that has made its decision. In a parliamentary system, if important legislation proposed by the incumbent prime minister and his cabinet is "voted down" by a majority of the members of parliament then it is considered a vote of no confidence. To emphasize that particular point, a prime minister will often declare a particular legislative vote to be a matter of confidence at the first sign of reluctance on the part of legislators from his or her own party. If a government loses a parliamentary vote of confidence, then the incumbent government must then either resign or call elections to be held, a consequence few backbenchers are willing to endure. Hence, a no confidence vote in some parliamentary countries, like Britain, only occurs a few times in a century. In 1931, David Lloyd George told a select committee: "Parliament has really no control over the executive; it is a pure fiction." (Schlesinger 1982)

By contrast, if a presidential legislative initiative fails to pass a legislature controlled by the president's party (e.g. the Clinton health care plan of 1993 in the United States), it may damage the president's political standing and that of his party, but generally has no immediate effect on whether or not the president completes his term.

Speed and decisiveness

Some supporters of presidential systems claim that presidential systems can respond more rapidly to emerging situations than parliamentary ones. A prime minister, when taking action, needs to retain the support of the legislature, but a president is often less constrained. In Why England Slept, future U.S. president John F. Kennedy argued that British prime ministers Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain were constrained by the need to maintain the confidence of the Commons.

Other supporters of presidential systems sometimes argue in the exact opposite direction, however, saying that presidential systems can slow decision-making to beneficial ends. Divided government, where the presidency and the legislature are controlled by different parties, is said to restrain the excesses of both parties, and guarantee bipartisan input into legislation. In the United States, Republican Congressman Bill Frenzel wrote in 1995:

- There are some of us who think gridlock is the best thing since indoor plumbing. Gridlock is the natural gift the Framers of the Constitution gave us so that the country would not be subjected to policy swings resulting from the whimsy of the public. And the competition—whether multi-branch, multi-level, or multi-house—is important to those checks and balances and to our ongoing kind of centrist government. Thank heaven we do not have a government that nationalizes one year and privatizes next year, and so on ad infinitum. (Checks and Balances, 8)

Stability

Although most parliamentary governments go long periods of time without a no confidence vote, Italy, Israel, and the French Fourth Republic have all experienced difficulties maintaining stability. When parliamentary systems have multiple parties, and governments are forced to rely on coalitions, as they often do in nations that use a system of proportional representation, extremist parties can theoretically use the threat of leaving a coalition to further their agendas.

Many people consider presidential systems more able to survive emergencies. A country under enormous stress may, supporters argue, be better off being led by a president with a fixed term than rotating premierships. France during the Algerian controversy switched to a semi-presidential system as did Sri Lanka during its civil war, while Israel experimented with a directly elected prime minister in 1992. In France and Sri Lanka, the results are widely considered to have been positive. However, in the case of Israel, an unprecedented proliferation of smaller parties occurred, leading to the restoration of the previous system of selecting a prime minister.

The fact that elections are fixed in a presidential system is considered by supporters a welcome "check" on the powers of the executive, contrasting parliamentary systems, which may allow the prime minister to call elections whenever they see fit or orchestrate their own vote of no confidence to trigger an election when they cannot get a legislative item passed. The presidential model is said to discourage this sort of opportunism, and instead forces the executive to operate within the confines of a term they cannot alter to suit their own needs.

Proponents of the presidential system also argue that stability extends to the cabinets chosen under the system, compared to a parliamentary system where cabinets must be drawn from within the legislative branch. Under the presidential system, cabinet members can be selected from a much larger pool of potential candidates. This allows presidents the ability to select cabinet members based as much or more on their ability and competency to lead a particular department as on their loyalty to the president, as opposed to parliamentary cabinets, which might be filled by legislators chosen for no better reason than their perceived loyalty to the prime minister. Supporters of the presidential system note that parliamentary systems are prone to disruptive "cabinet shuffles" where legislators are moved between portfolios, whereas in presidential system cabinets (such as the United States Cabinet), cabinet shuffles are unusual.

Criticism and disadvantages

Critics generally claim three basic disadvantages for presidential systems:

- Tendency towards authoritarianism — some political scientists say presidentialism raises the stakes of elections, exacerbates their polarization and can lead to authoritarianism (Linz).

- Political gridlock — the separation of powers of a presidential system establishes the presidency and the legislature as two parallel structures. Critics argue that this can create an undesirable and long-term political gridlock whenever the president and the legislative majority are from different parties, which is common because the electorate usually expects more rapid results from new policies than are possible (Linz, Mainwaring and Shugart). In addition, this reduces accountability by allowing the president and the legislature to shift blame to each other.

- Impediments to leadership change — presidential systems often make it difficult to remove a president from office early, for example after taking actions that become unpopular.

Tendency towards authoritarianism

A prime minister without majority support in the legislature must either form a coalition or, if able to lead a minority government, govern in a manner acceptable to at least some of the opposition parties. Even with a majority government, the prime minister must still govern within (perhaps unwritten) constraints as determined by the members of his party—a premier in this situation is often at greater risk of losing his party leadership than his party is at risk of losing the next election. On the other hand, winning the presidency is a winner-take-all, zero-sum game. Once elected, a president might be able to marginalize the influence of other parties and exclude rival factions in his own party as well, or even leave the party whose ticket he was elected under. The president can thus rule without any party support until the next election or abuse his power to win multiple terms, a worrisome situation for many interest groups. Yale political scientist Juan Linz argues that:

| “ | The danger that zero-sum presidential elections pose is compounded by the rigidity of the president's fixed term in office. Winners and losers are sharply defined for the entire period of the presidential mandate... losers must wait four or five years without any access to executive power and patronage. The zero-sum game in presidential regimes raises the stakes of presidential elections and inevitably exacerbates their attendant tension and polarization. | ” |

Constitutions that only require plurality support are said to be especially undesirable, as significant power can be vested in a person who does not enjoy support from a majority of the population.

Some political scientists say that presidential systems are not constitutionally stable and have difficulty sustaining democratic practices, noting that presidentialism has slipped into authoritarianism in many of the countries in which it has been implemented. According to political scientist Fred Riggs, presidentialism has fallen into authoritarianism in nearly every country it has been attempted.[2][3] Political sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset pointed out that this has taken place in political cultures not conducive to democracy and that militaries have tended to play a prominent role in most of these countries. On the other hand, an often-cited list of the world's 22 older democracies includes only two countries (Costa Rica and the United States) with presidential systems.

In a presidential system, the legislature and the president have equal mandates from the public. Conflicts between the branches of government might not be reconciled. When president and legislature disagree and government is not working effectively, there is a strong incentive to use extra-constitutional measures to break the deadlock. Of the three common branches of government, the executive is in the best position to use extra-constitutional measures, especially when the president is head of state, head of government, and commander-in-chief of the military. By contrast, in a parliamentary system where the often-ceremonial head of state is either a constitutional monarch or (in the case of a parliamentary republic) an experienced and respected figure, given some political emergency there is a good chance that even a ceremonial head of state will be able to use emergency reserve powers to restrain a head of government acting in an emergency extra-constitutional manner — this is only possible because the head of state and the head of government are not the same person.

Ecuador is sometimes presented as a case study of democratic failures over the past quarter-century. Presidents have ignored the legislature or bypassed it altogether. One president had the National Assembly teargassed, while another disagreed with congress until he was kidnapped by paratroopers. From 1979 through 1988, Ecuador staggered through a succession of executive-legislative confrontations that created a near permanent crisis atmosphere in the policy. In 1984, President León Febres Cordero tried to physically bar new Congressionally appointed supreme court appointees from taking their seats.

In Brazil, presidents have accomplished their objectives by creating executive agencies over which Congress had no say.

Dana D. Nelson in her 2008 book Bad for Democracy[4] sees the office of the President of the United States as essentially undemocratic[5] and characterizes presidentialism as worship of the president by citizens, which she believes undermines civic participation.[5]

Political gridlock

Some political scientists speak of the "failure of presidentialism" because the separation of powers of a presidential system often creates undesirable long-term political gridlock and instability whenever the president and the legislative majority are from different parties. This is common because the electorate often expects more rapid results than are possible from new policies and switches to a different party at the next election. These critics, including Juan Linz, argue that this inherent political instability can cause democracies to fail, as seen in such cases as Brazil and Chile.

Lack of accountability

In such cases of gridlock, presidential systems are said by critics not to offer voters the kind of accountability seen in parliamentary systems. It is easy for either the president or the legislature to escape blame by shifting it to the other. Describing the United States, former Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon said "the president blames Congress, the Congress blames the president, and the public remains confused and disgusted with government in Washington".[6]

An example is the increase in the federal debt of the United States that occurred during the presidency of Republican Ronald Reagan. Arguably, the deficits were the product of a bargain between President Reagan and the Democratic Speaker of the House of Representatives, Tip O'Neill. O'Neill agreed to tax cuts favored by Reagan, and in exchange Reagan agreed to budgets that did not restrain spending to his liking. In such a scenario, each side can say they are displeased with the debt, plausibly blame the other side for the deficit, and still claim success.

Impediments to leadership change

Another alleged problem of presidentialism is that it is often difficult to remove a president from office early. Even if a president is "proved to be inefficient, even if he becomes unpopular, even if his policy is unacceptable to the majority of his countrymen, he and his methods must be endured until the moment comes for a new election."[7] John Tyler was elected Vice President and assumed the presidency because William Henry Harrison died after thirty days in office. Tyler blocked the Whig agenda, was loathed by his nominal party, but remained firmly in control of the executive branch. Most presidential systems provide no legal means to remove a president simply for being unpopular or even for behaving in a manner that might be considered unethical or immoral provided it is not illegal. This has been cited as the reason why many presidential countries have experienced military coups to remove a leader who is said to have lost his mandate.

Parliamentary systems can quickly remove unpopular leaders by a vote of no confidence, a procedure that serves as a "pressure release valve" for political tension. Votes of no confidence are easier to achieve in minority government situations, but even if the unpopular leader heads a majority government, he is often in a less secure position than a president. Usually in parliamentary systems a basic premise is that if a premier's popularity sustains a serious enough blow and the premier does not as a matter of consequence offer to resign prior to the next election, then those members of parliament who would persist in supporting the premier will be at serious risk of losing their seats. Therefore, especially in parliaments with a strong party system, other prominent members of the premier's party have a strong incentive to initiate a leadership challenge in hopes of mitigating damage to their party. More often than not, a premier facing a serious challenge resolves to save face by resigning before being formally removed—Margaret Thatcher's relinquishing of her premiership being a prominent example.

On the other hand, while removing a president through impeachment is allowed by most constitutions, impeachment proceedings often can be initiated only in cases where the president has violated the constitution or broken the law. Impeachment is often made difficult; by comparison the removal a party leader is normally governed by the (often less formal) rules of the party. Nearly all parties (including governing parties) have a relatively simple process for removing their leaders.

Furthermore, even when impeachment proceedings against a sitting president are successful, whether by causing his removal from office or by compelling his resignation, the legislature usually has little or no discretion in determining the ousted president's successor, since presidential systems usually adhere to a rigid succession process which is enforced the same way regardless of how a vacancy in the presidency comes about. The usual outcome of a presidency becoming vacant is that a vice president automatically succeeds to the presidency. Vice presidents are usually chosen by the president, whether as a running mate who elected alongside the president or appointed by a sitting president, so that when a vice president succeeds to the presidency it is probable that he will continue many or all the policies of the former president. A prominent example of such an accession would be the elevation of Vice President Gerald Ford to the U.S. Presidency after Richard Nixon agreed to resign in the face of virtually certain impeachment and removal, a succession that took place notwithstanding the fact that Ford had only assumed the Vice Presidency after being appointed by Nixon to replace Spiro Agnew, who had also resigned due to scandal. In some cases, particularly when the would-be successor to a presidency is seen by legislators as no better (or even worse) than a president they wish to see removed, there may be a strong incentive to abstain from pursuing impeachment proceedings even if there are legal grounds to do so.

Since prime ministers in parliamentary systems must always retain the confidence of the legislature, in cases where a prime minister suddenly leaves office there is little point in anyone without a reasonable prospect of gaining that legislative confidence attempting to assume the premiership. This ensures that whenever a premiership becomes vacant (or is about to become vacant), legislators from the premier's party will always play a key role in determining the leader's permanent successor. In theory this could be interpreted to support an argument that a parliamentary party ought to have the power to elect their party leader directly, and indeed, at least historically, parliamentary system parties' leadership electoral procedures usually called for the party's legislative caucus to fill a leadership vacancy by electing a new leader directly by and from amongst themselves, and for the whole succession process to be completed within as short a time frame as practical. Today, however, such a system is not commonly practiced and most parliamentary system parties' rules provide for a leadership election in which the general membership of the party is permitted to vote at some point in the process (either directly for the new leader or for delegates who then elect the new leader in a convention), though in many cases the party's legislators are allowed to exercise a disproportionate influence in the final vote. Whenever a leadership election becomes necessary on account of a vacancy arising suddenly, an interim leader (often informally called the interim prime minister in cases where this involves a governing party) will be selected by the parliamentary party, usually with the stipulation or expectation that the interim leader will not be a candidate for the permanent leadership. Some parties, such as the British Conservative Party, employ some combination of both aforementioned electoral processes to select a new leader. In any event, a prime minister who is forced to leave office due to scandal or similar circumstance will usually have little if any ability to influence his party on the final selection of a new leader and anyone seen to be having close ties to such a prime minister will have limited if any serious prospect of being elected the new leader. Even in cases when an outgoing prime minister is leaving office voluntarily, it is often frowned on for an outgoing or former premier to engage in any overt attempt to influence the election (for example, by endorsing a candidate in the leadership election), in part because a party in the process of selecting a new leader usually has a strong incentive to foster a competitive leadership election in order to stimulate interest and participation in the election, which in turn encourages the sale of party memberships and support for the party in general.

Walter Bagehot criticized presidentialism because it does not allow a transfer in power in the event of an emergency.

- Under a cabinet constitution at a sudden emergency the people can choose a ruler for the occasion. It is quite possible and even likely that he would not be ruler before the occasion. The great qualities, the imperious will, the rapid energy, the eager nature fit for a great crisis are not required—are impediments—in common times. A Lord Liverpool is better in everyday politics than a Chatham—a Louis Philippe far better than a Napoleon. By the structure of the world we want, at the sudden occurrence of a grave tempest, to change the helmsman—to replace the pilot of the calm by the pilot of the storm.

- But under a presidential government you can do nothing of the kind. The American government calls itself a government of the supreme people; but at a quick crisis, the time when a sovereign power is most needed, you cannot find the supreme people. You have got a congress elected for one fixed period, going out perhaps by fixed installments, which cannot be accelerated or retarded—you have a president chosen for a fixed period, and immovable during that period: ..there is no elastic element... you have bespoken your government in advance, and whether it is what you want or not, by law you must keep it ...[8]

Opponents of the presidential system note that years later, Bagehot's observation came to life during World War II, when Neville Chamberlain was replaced with Winston Churchill.

However, supporters of the presidential system question the validity of the point. They argue that if presidents were not able to command some considerable level of security in their tenures, their direct mandates would be worthless. They further counter that republics such as the United States have successfully endured war and other crises without the need to change heads of state. Supporters argue that presidents elected in a time of peace and prosperity have proven themselves perfectly capable of responding effectively to a serious crisis, largely due to their ability to make the necessary appointments to his cabinet and elsewhere in government or by creating new positions to deal with new challenges. One prominent, recent example would be the appointment of a Secretary of Homeland Security following the September 11 attacks in the United States.

Some supporters of the presidential system counter that impediments to a leadership change, being that they are little more than an unavoidable consequence of the direct mandate afforded to a president, are thus a strength instead of a weakness in times of crisis. In such times, a prime minister might hesitate due to the need to keep parliament's support, whereas a president can act without fear of removal from office by those who might disapprove of his actions. Furthermore, even if a prime minister does manage to successfully resolve a crisis (or multiple crises), that does not guarantee and he or she will possess the political capital needed to remain in office for a similar, future crisis. Unlike what would be possible in a presidential system, a perceived crisis in the parliamentary system might give disgruntled backbenchers or rivals an opportunity to launch a vexing challenge for a prime minister's leadership. As noted above, in such situations a prime minister often resigns if they even moderately doubt their ability to endure a challenge, and there is no guarantee that the sudden accession of an unproven prime minister during a crisis will be a change for the better—the ouster of Thatcher (who, after successfully prosecuting the Falklands War, was nevertheless compelled to resign in the midst of the Persian Gulf Crisis) is seen as an example by those who argue her successor, John Major, proved less able to defend British interests in the ensuing Gulf War.

Finally, many have criticized presidential systems for their alleged slowness to respond to their citizens' needs. Often, the checks and balances make action difficult. Walter Bagehot said of the American system, "the executive is crippled by not getting the law it needs, and the legislature is spoiled by having to act without responsibility: the executive becomes unfit for its name, since it cannot execute what it decides on; the legislature is demoralized by liberty, by taking decisions of others [and not itself] will suffer the effects".[8]

Defenders of Presidential systems argue that a parliamentary system operating in a jurisdiction with strong ethnic or sectarian tensions will tend to ignore the interests of minorities or even treat them with contempt - the first half century of government in Northern Ireland is often cited as an example - whereas presidential systems ensure that minority wishes and rights cannot be disregarded, thus preventing a "Tyranny of the majority" and vice versa protect the wishes and rights of the majority from abuse by a legislature or an executive that holds a contrary viewpoint especially when there are frequent, scheduled elections. On the other hand, supporters of parliamentary systems contend that the strength and independence of the judiciary is the more decisive factor when it comes to protection of minority rights.

British-Irish philosopher and MP Edmund Burke stated that an official should be elected based on "his unbiased opinion, his mature judgment, his enlightened conscience", and therefore should reflect on the arguments for and against certain policies before taking positions and then act out on what an official would believe is best in the long run for one's constituents and country as a whole even if it means short-term backlash. Thus Defenders of Presidential systems hold that sometimes what is wisest may not always be the most popular decision and vice versa.

Differences from a parliamentary system

A number of key theoretical differences exist between a presidential and a parliamentary system:

- In a presidential system, the central principle is that the legislative and executive branches of government are separate. This leads to the separate election of president, who is elected to office for a fixed term, and only removable for gross misdemeanor by impeachment and dismissal. In addition he or she does not need to choose cabinet members commanding the support of the legislature. By contrast, in parliamentarianism, the executive branch is led by a council of ministers, headed by a Prime Minister, who are directly accountable to the legislature and often have their background in the legislature (regardless of whether it is called a "parliament", an "assembly", a "diet", or a "chamber").

- As with the president's set term of office, the legislature also exists for a set term of office and cannot be dissolved ahead of schedule. By contrast, in parliamentary systems, the prime minister needs to survive a vote of confidence otherwise a new election must be called. The legislature can typically be dissolved at any stage during its life by the head of state, usually on the advice of either Prime Minister alone, by the Prime Minister and cabinet, or by the cabinet.

- In a presidential system, the president usually has special privileges in the enactment of legislation, namely the possession of a power of veto over legislation of bills, in some cases subject to the power of the legislature by weighted majority to override the veto. The legislature and the president are thus expected to serve as checks and balances on each other's powers.

- Presidential system presidents may also be given a great deal of constitutional authority in the exercise of the office of Commander in Chief, a constitutional title given to most presidents. In addition, the presidential power to receive ambassadors as head of state is usually interpreted as giving the president broad powers to conduct foreign policy. Though semi-presidential systems may reduce a president's power over day-to-day government affairs, semi-presidential systems commonly give the president power over foreign policy.

Presidential systems also have fewer ideological parties than parliamentary systems. Sometimes in the United States, the policies preferred by the two parties have been very similar (but see also polarization). In the 1950s, during the leadership of Lyndon B. Johnson, the Senate Democrats included the right-most members of the chamber—Harry Byrd and Strom Thurmond, and the left-most members—Paul Douglas and Herbert Lehman. This pattern does not prevail in Latin American presidential democracies.

Overlapping elements

In practice, elements of both systems overlap. Though a president in a presidential system does not have to choose a government under the legislature, the legislature may have the right to scrutinize his or her appointments to high governmental office, with the right, on some occasions, to block an appointment. In the United States, many appointments must be confirmed by the Senate, although once confirmed an appointee can only be removed against the president's will through impeachment. By contrast, though answerable to parliament, a parliamentary system's cabinet may be able to make use of the parliamentary 'whip' (an obligation on party members in parliament to vote with their party) to control and dominate parliament, reducing parliament's ability to control the government.

Sovereign republics with a presidential system of government

Afghanistan

Afghanistan Angola

Angola Argentina

Argentina Benin

Benin Bolivia

Bolivia Brazil

Brazil Burundi

Burundi Chile

Chile Colombia

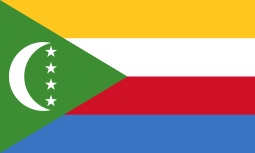

Colombia Comoros

Comoros Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cyprus

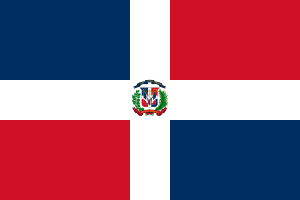

Cyprus Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Ecuador

Ecuador El Salvador

El Salvador Gambia, The

Gambia, The Ghana

Ghana Guatemala

Guatemala Honduras

Honduras Indonesia

Indonesia Iran[9]

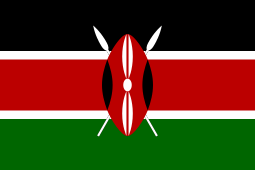

Iran[9] Kenya

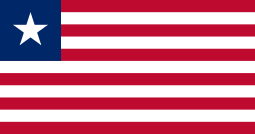

Kenya Liberia

Liberia Malawi

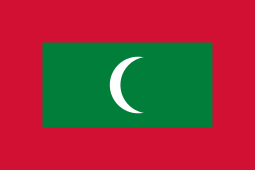

Malawi Maldives

Maldives Mexico

Mexico Nicaragua

Nicaragua Nigeria

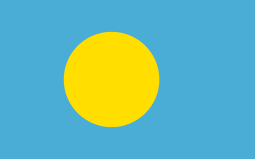

Nigeria Palau

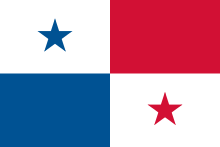

Palau Panama

Panama Paraguay

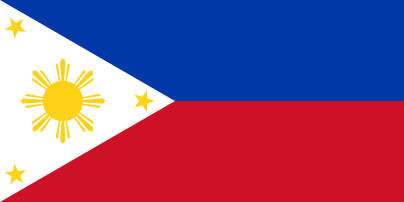

Paraguay Philippines

Philippines Seychelles

Seychelles Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone South Africa

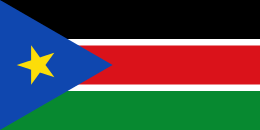

South Africa South Sudan

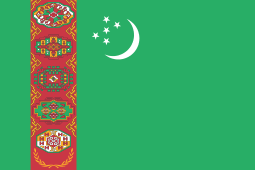

South Sudan Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan United States

United States Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zambia

Zambia Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Presidential systems with a prime minister

The following countries have presidential systems where a post of prime minister exists alongside with that of president. Differently from other systems, however, the president is still both the head state and government and the prime minister's roles are mostly to assist the president. Belarus and Kazakhstan, where the prime minister is effectively the head of government and the president the head of state, are exceptions.

Belarus

Belarus Cameroon

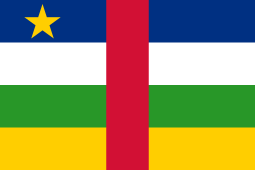

Cameroon Central African Republic

Central African Republic Chad

Chad Congo, Republic of the

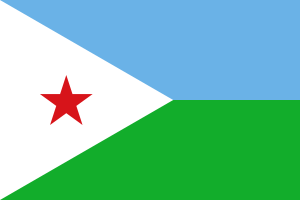

Congo, Republic of the Djibouti

Djibouti Gabon

Gabon Guinea (Guinea-Conakry)

Guinea (Guinea-Conakry) Guyana

Guyana Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire)

Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire) Kazakhstan[10]

Kazakhstan[10] Korea, South

Korea, South Peru

Peru Sudan

Sudan Tajikistan

Tajikistan Tanzania

Tanzania Togo

Togo Uganda

Uganda Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

See also

- List of countries by system of government

- Parliamentary system & Westminster system

- Semi-presidential system

- Coalition government

Notes and references

- ↑ The "presidential" model implies that the Chief Executive is elected by all those members of the electoral body: Buonomo, Giampiero (2003). "Titolo V e "forme di governo": il caso Abruzzo (dopo la Calabria)". Diritto&Giustizia edizione online. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ "Presidentialism versus Parliamentarism: Implications for Representativeness and Legitimacy". International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale De Science Politique. 18 (3): 258. 1997.

- ↑ "Conceptual homogenization of a heterogeneous field: Presidentialism in comparative perspective". Comparing Nations: Concepts, Strategies, Substance: 72–152. 1994.

- ↑ Nelson, Dana D. (2008). Bad for Democracy: How the Presidency Undermines the Power of the People. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-8166-5677-6.

- 1 2 David Sirota (August 22, 2008). "Why cult of presidency is bad for democracy". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ Sundquist, James (1992). Constitutional Reform and Effective Government. Brookings Institution Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Balfour. "Introduction". The English Constitution.

- 1 2 Balfour. "The Cabinet". The English Constitution.

- ↑ Iran combines the forms of a presidential republic, with a president elected by universal suffrage, and a theocracy, with a Supreme Leader who is ultimately responsible for state policy, chosen by the elected Assembly of Experts. Candidates for both the Assembly of Experts and the presidency are vetted by the appointed Guardian Council.

- ↑ "Nazarbaev Signs Kazakh Constitutional Amendments Into Law". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 10 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017. For more information: please see Abdurasulov, Abdujalil (6 March 2017). "Kazakhstan constitution: Will changes bring democracy?". BBC News. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

External links

- The Great Debate: Parliament versus Congress

- Castagnola, Andrea/Pérez-Liñán, Aníbal: Presidential Control of High Courts in Latin America: A Long-term View (1904-2006), in: Journal of Politics in Latin America, Hamburg 2009.